Stegotrachelus, WOODWARD & WHITE, 1926

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00505.x |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/D84F3D4C-1E46-D232-FCE8-FC0A77F28B2D |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Stegotrachelus |

| status |

|

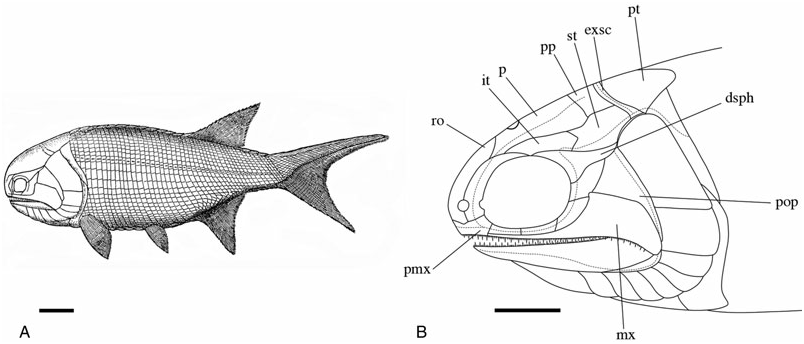

STEGOTRACHELUS WOODWARD & WHITE, 1926

TYPE SPECIES STEGOTRACHELUS FINLAYI WOODWARD & WHITE, 1926

Revised diagnosis

See Woodward & White (1926: 567) and Gardiner (1963: 295) with the following amendments: – Stegotrachelus finlayi is an early actinopterygian differing from Moythomasia spp. by one or more of the following character state combinations: parietals up to two times longer than the postparietals; contact between the intertemporal and supratemporal anterior to that between the parietal and postparietal; a T-shaped dermosphenotic with a posterior ramus up to one-third of the length of the entire bone; contact between intemporal and nasal excluding dermosphenotic–parietal contact; intemporal–nasal contact; an absence of remodelled porous ganoine on the lower jaw; a slight nuchal hump; one pair of extrascapulars; polymorphic fringing fulcra; an anal fin shifted posterior relative to the dorsal fin; a hypochordal lobe shorter than the chordal lobe; and the following fin-ray counts: dorsal-fin rays, 39–42; analfin rays, 42–48; pectoral-fin rays, 17–21; pelvic-fin rays, 18–20; caudal-fin rays, 92–99. See scalecounting data for additional details.

DESCRIPTION

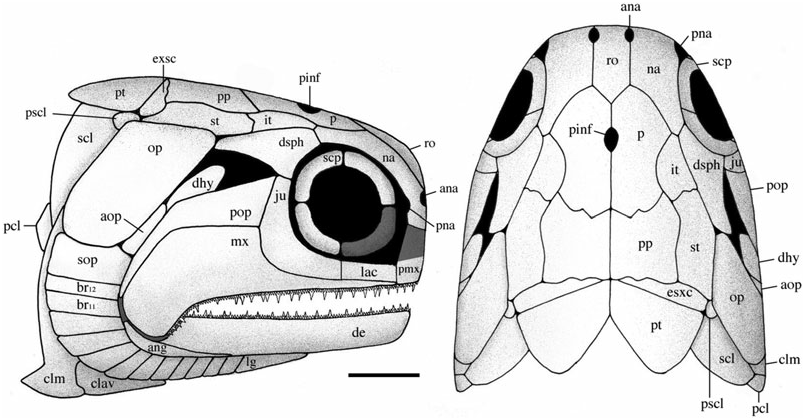

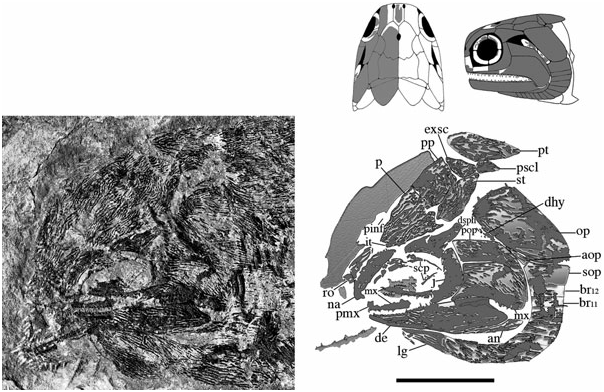

Skull roof

The skull roof is composed of the parietals, postparietals, supratemporals, intertemporals, dermosphenotics, and extrascapulars. It is about as wide as deep, anteriorly pierced by a pineal foramen, and laterally bound by the operculogular series. Although cephalic line canals are probably present, their path amongst excessive dermal ridging and pitting cannot be recognized, and thus have not been reconstructed. Material is limited to three specimens [ BMNH P.13410, NMS G 2002.26 View Materials .1360, NMS 1973.10.35.(P.)], although a lateral profile of the marginal roofing bones is preserved in BMNH P.13407 and NMS G 2002.26 View Materials .1384.

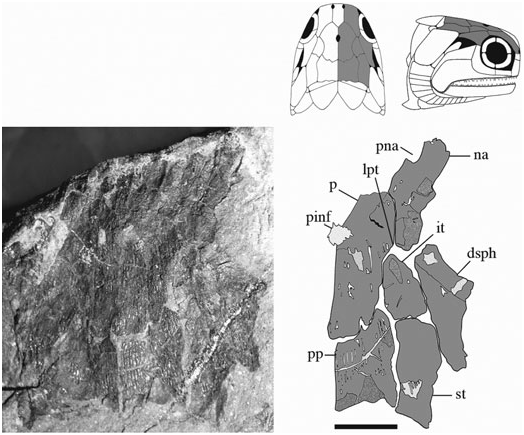

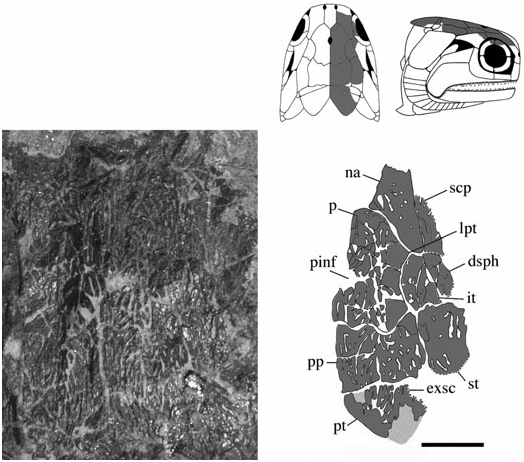

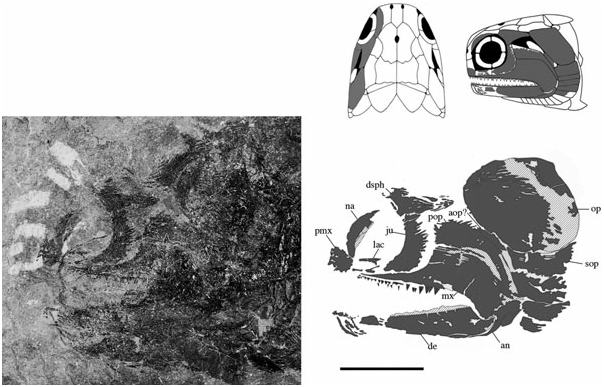

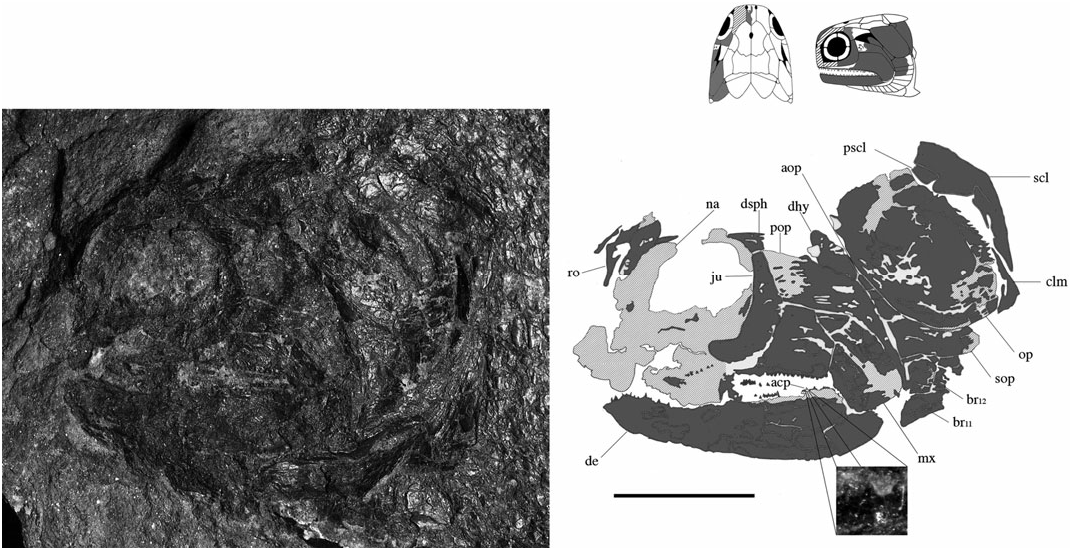

Parietals (p) ( Figs 3–6 View Figure 3 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 ): These bones are essentially elongate-pentagonal with a shortened and concave lateral wall. They meet at a smooth median suture [NMS 1973.10.35.(P.)] with a wide angled V-shaped depression (BMNH P.20310) for the rostral bone at their anterior margin. The only elements well preserved as a pair are visible in NMS 1973.10.35.(P.) ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). The posterior margin of each of these parietals is laterally rounded and medially deep, interrupted only by a slight recess penetrated by the anterior mid-width projection of the postparietal. A distinct parietal tab projects laterally in all three specimens and divides (lateral) parietal– intertemporal contact from (anterolateral) parietal– nasal contact. The right parietal is well illustrated in NMS G 2002.26.1360 ( Fig. 5 View Figure 5 ) and the left (anteriorly broken) parietal is visible in BMNH P.13410 ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ). A pineal foramen is present in all three specimens, although its position is variable. It is located about mid-length in the two smaller specimens (BMNH P.13410 and NMS G 2002.26.1360), but is restricted to the anterior third of the parietal in the largest specimen [NMS 1973.10.35.(P.)]. There is no evidence of a pineal plate as observed in Cheirolepis , Dialipina , or Meemannia ( Pearson & Westoll, 1979; Arratia & Cloutier, 1996; Schultze & Cumbaa, 2001; Zhu et al., 2006). Dermal ornamentation is easily visible in NMS G 2002.26.1360 and BMNH P.13410, and consists of a dense labyrinth of interconnected longitudinal ridges and infrequent marginal tubercles.

The parietals were not included in the ‘skull-cap’ of the original S. finlayi reconstruction ( Fig. 1A View Figure 1 ); however, they were incorporated into Gardiner’s (1963) redescription ( Fig. 1B View Figure 1 ) ( Woodward & White, 1926; Gardiner, 1963). Gardiner’s reconstruction is accurate in recognizing the pineal foramen and lateral parietal tab, but inaccurate in estimating the anterior and posterior limits of the parietal. NMS 1973.10.35.(P.) and NMS G 2002.26.1360 ( Figs 4 View Figure 4 , 5 View Figure 5 ) show that 25–35% of the parietal extends anterior to its lateral tab, and posteriorly terminates just anterior to the supratemporal.

Postparietals (pp) ( Figs 3–6 View Figure 3 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 ): The postparietals are half as long as the parietals, subquadrate to slightly rectangular, and largely symmetrical [ NMS G 2002.26 View Materials .1360, BMNH P.13410, NMS 1973.10.35.(P.)]. The posterior postparietal margin is M-shaped [ NMS 1973.10.35.(P.); Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ] and posteriorly bound by the extrascapular ( BMNH P.13410; Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ). The lateral margin is posteriorly straight and anteriorly convex [ NMS 1973.10.35.(P.)]. At about mid-length, the lateral surface bows outward to contact the supratemporal laterally and intertemporal anterolaterally. The anterior postparietal margin is W-shaped, and most elaborate in NMS 1973.10.35.(P.). The lateral wing expands and wraps around the posterolateral edge of the parietal whereas the mid-width peak penetrates the posterior parietal recess. The left half of the skull roof is poorly preserved and laterally warped [ NMS 1973.10.35.(P.), NMS G 2002.26.1360]. Thus, poor preservation may explain the slight asymmetry in the lateral margin of the left postparietal relative to its well-preserved right counterpart. Lateral expansion is less broad in the smaller two specimens ( BMNH P.13410 and NMS G 2002.26.1360) relative to NMS 1973.10.35.(P.). However, despite this slight variation, the postparietal consistently contacts the intertemporal at its anterior-most extension in all three specimens .

Similar to the parietals, the postparietals were not included in the original 1926 reconstruction of S. finlayi ( Woodward & White, 1926) . They were incorporated into Gardiner’s (1963) redescription ( Fig. 1B View Figure 1 ) as relatively squat straight rectangular bones about a third of the length of the parietals. They were shown to terminate behind the anterior margin of the supratemporal and to not contact the intertemporal ( Gardiner, 1963). These observations are not confirmed as all three skull roof specimens show the postparietal up to half as long as the parietal, terminating at least as far anterior as the supratemporal, and possessing an anterolateral edge that contacts the posteromedial margin of the intertemporal [NMS 1973.10.35.(P.), NMS G 2002.26.1360, BMNH P.13410; Figs 4–6 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 ].

Supratemporals (st) ( Figs 3–6 View Figure 3 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 ): The supratemporal is medially straight and rectangular in BMNH P.13410 and in NMS G 2002.26 View Materials .1360, but anteriorly tapers in NMS 1973.10.35.(P.) in association with the expansion of the lateral postparietal margin. Every contour of the supratemporal reflects its unique position with respect to neighbouring bones. The slightly pointed anterior margin ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ) projects into the posteriorly recessed intertemporal ( BMNH P.13410). The kinked lateral edge reflects its position adjacent to the dermosphenotic and operculum, respectively [ NMS 1973.10.35.(P.); Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ]. Its posterolateral expansion combines with the postparietal to form a pocket within which the extrascapular resides [ NMS 1973.10.35.(P.), BMNH P.13410]. Ornament is primarily preserved in the smaller two skull roof specimens ( BMNH P.13410, NMS G 2002.26.1360) and follows a similar pattern seen on the parietal and postparietal. The supratemporal is also laterally visible in the holotype ( BMNH P.13407) where it is dorsally adjacent to the operculum .

Similar to previous skull roofing bones, the supratemporal was not reconstructed in 1926 but was included in Gardiner’s (1963) redescription. Gardiner correctly identified the lateral kink that separates anterior (supratemporal–dermosphenotic) and posterior (supratemporal–operculum) divisions. However, new observations confirm that the supratemporal is slightly pointed anteriorly (BMNH P.13410) and posterolaterally expanded [BMNH P.13410, NMS 1973.10.35.(P.)]. These features are not included in the 1963 reconstruction.

Intertemporals (it) ( Figs 3–6 View Figure 3 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 ): The intertemporal is a small bone just anterior to the supratemporal and characterized by a slight recess into which the anterior margin of the supratemporal extends (NMS G 2002.26.1360, BMNH P.13410). The intertemporal is half the length of the dermosphenotic [NMS 1973.10.35.(P.)], anteriorly contacts the nasal [BMNH P.13410, NMS G 2002.26.1360, NMS 1973.10.35.(P.)], and is of similar relative size and shape to the intertemporal in ‘Mimia’ toombsi and Moythomasia ( Jessen, 1968; Gardiner, 1984). Diagonal ridges of dermal ornament are most pronounced in NMS G 2002.26.1360 and BMNH P.13410 ( Figs 5 View Figure 5 , 6 View Figure 6 ).

The intertemporal is the last skull roofing bone recognized by Gardiner (1963) that was not included in the original S. finlayi reconstruction. Gardiner’s redescription accurately illustrated the positional relationship of the intertemporal to neighbouring bones, but incorrectly identified its V-shaped posterior extension and relatively long margin of contact with the nasal.

Dermosphenotics (dsph) ( Figs 3–8 View Figure 3 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 ): The dermosphenotic is comparatively large, T- or wedge-shaped, and preserved in several specimens [BMNH P.13410, P.13407, P.20313, NMS 1973.10.35.(P.), NMS G 2002.26.1360]. The posterior ramus of the dermosphenotic and lateral margin of the supratemporal abut just anterior to the operculum to form a pocket into which the dorsal-most edge of the operculum extends [NMS 1973.10.35.(P.), BMNH P.13410, P.13407]. Dermosphenotic–nasal contact is midorbital in BMNH P.13410 ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ); however, appears more posteriorly positioned in BMNH P.13407 ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ) and NMS 1973.10.35.(P.) ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). Dermal ornament is composed of anteroposteriorly directed ridges (BMNH P.13407, P.13410).

The dermosphenotic reconstructed by Woodward & White (1926) and Gardiner (1963) is mostly accurate, although dermosphenotic–nasal contact in NMS 1973.10.35.(P.) and BMNH P.13407 is more posterior than in either reconstruction. Additionally, the dorsoposterior curve and pointed tip interpreted previously ( Woodward & White, 1926; Gardiner, 1963) are not confirmed [BMNH P.13410, P.13407, NMS 1973.10.35.(P.)]. NMS 1973.10.35.(P.) clearly shows the dermosphenotic to curve ventrocaudally and to terminate with a moderately blunt margin similar to Moythomasia nitida ( Jessen, 1968: pl. 12).

Extrascapulars (exsc) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 5 View Figure 5 , 6 View Figure 6 ): The extrascapulars are transversely elongate bones that narrow medially toward the midline of the skull. There is a single pair similar to all other Devonian actinopterygians except Moythomasia and Osorioichthys , which have two extrascapular pairs ( Jessen, 1968; Gardiner, 1984; Taverne, 1997). They are posterolaterally bound by the combination of post-temporals, supratemporals, and presupracleithra like Moythomasia ( Jessen, 1968; Gardiner, 1984). Ornament consists of rostrocaudally directed ridges that anteromesially bend about 45° along their anterior margins (BMNH P.13410; Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ).

Woodward & White (1926) reconstructed the left extrascapular as a vague set of lines immediately dorsal to the operculum, but unresolved medially. Gardiner’s (1963) redescription drew upon this same pattern of a narrow extrascapular, but attempted to clarify the uncertain medial detail by interpreting this thin bone as equally deep along its entire transverse axis. The evidence from BMNH P.13410 ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ) does not support either interpretation, but instead shows a laterally broad extrascapular with the supratemporal and presupracleithrum (not extrascapular) immediately dorsal to the operculum.

Snout

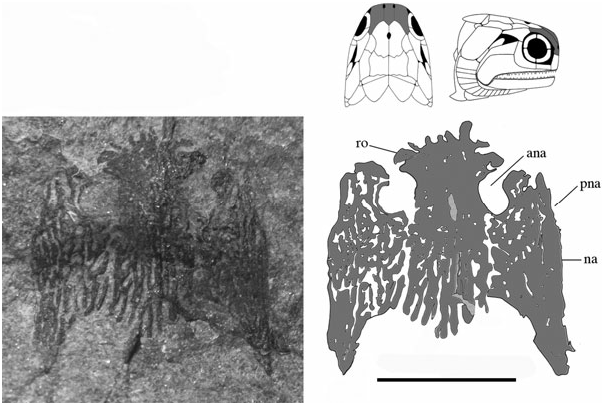

The snout of S. finlayi is fairly blunt and composed of the nasals, premaxillae, and rostral. The nasals are paired notched elements that form the anterior rim of a very large orbit. Premaxillae are rarely preserved but appear to abut medially and separate the median rostral from the oral margin. Considering the poor preservation of ventral and dorsal portions of nasal and premaxillary elements, respectively, the reconstruction of this portion of the snout is somewhat provisional.

Rostral (ro) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 6 View Figure 6 , 8 View Figure 8 , 9 View Figure 9 ): The rostral is anterolaterally notched and contributes to the medial margins of both anterior nares. It does not appear dentigerous, although is rostrally convoluted with dermal ornament producing a series of small knob-like projections ( Fig. 9 View Figure 9 ). Its width is invariable along its anteroposterior axis, although it anteriorly tapers to a very shallow point. The rostral is situated medial to the nasals, anterior to the parietals, and is present in several specimens [NMS 1973.10.35.(P.), BMNH P.13410, P.13418, NMS G 2002.26.1360, 2002.26.1384] but entirely complete only in BMNH P.20310. The ethmoid commissure may be present, although poor preservation medial to the anterior nares makes this interpretation difficult. Dermal ornament is rostrocaudally orientated and shows no evidence of the transverse ornamentation seen in Dialipina , Limnomis , or Cuneognathus ( Daeschler, 2000; Schultze & Cumbaa, 2001; Friedman & Blom, 2006). The absence of dentition in BMNH P.20310 and its similar shape to that of ‘Mimia’ toombsi and Moythomasia nitida suggests that the rostral of Stegotrachelus does not contribute to the jaw margin. Howqualepis and Osorioichthys are the only other Devonian actinopterygians with rostrals known to taper at their anterior edge ( Long, 1988; Taverne, 1997). Although Howqualepis is the only Devonian taxon whose anteriorly tapered rostral is dentigerous, it is also terminally straight, and therefore unlike that of S. finlayi .

With the possible exception of the ethmoid commissure, this description largely confirms Gardiner’s (1963) observations. However, NMS G 2002.26.1384 and BMNH P.13418 laterally profile a blunt snout and inconspicuous rostral, suggesting that this bone may be less anteriorly projecting than previously hypothesized.

Premaxillae (pmx) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 6 View Figure 6 , 7 View Figure 7 ): The premaxillae are small, poorly preserved bones most easily visible in BMNH P.13407 ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ), although also present in NMS G 2002.26.1384, BMNH P.13418, and P.13410 ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ). They appear to extend dorsally and contact the anterior edge of the nasal just medial to the external nares. Gardiner (1963) reconstructed the premaxilla as dorsoventrally shallow and anteroposteriorly elongate, superficially similar to the premaxilla of Howqualepis ( Gardiner, 1963; Long, 1988). Although the premaxillae in observed specimens appear less dorsoventrally shallow than Gardiner’s (1963) redescription, poor preservation makes a persuasive argument supporting the new interpretation difficult.

Nasals (na) ( Figs 3–9 View Figure 3 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 View Figure 9 ): The complete unbroken nasal of S. finlayi is dorsally visible in BMNH P.20310 ( Fig. 9 View Figure 9 ). Additionally, NMS 1973.10.35.(P.) profiles the nasal’s combined dorsal and lateral contribution to the anterior orbital margin ( Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ). It posteriorly contacts the dermosphenotic and contains a notch for the posterior naris that communicates with the orbital fenestra. Unlike Cheirolepis , which is characterized by a supraorbital and posteriorly notched preorbital anterior to the orbit, S. finlayi has no supra- or preorbital bones ( Pearson & Westoll, 1979; Arratia & Cloutier, 1996, 2004).

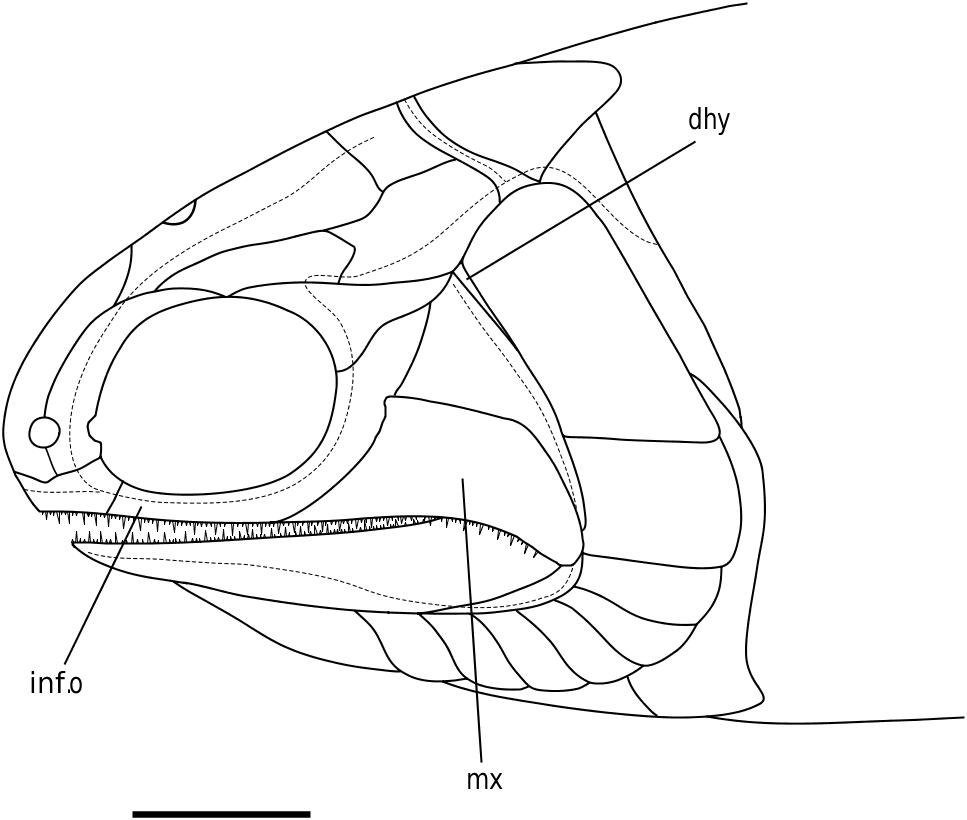

CHEEK, INFRAORBITAL BONES, AND

MANDIBULAR ARCH

The infraorbital series surrounds the posteroventral margin of the orbit. Although most Devonian actinopterygian taxa have two infraorbital bones, a few genera may have four (e.g. Tegeolepis and Kentuckia ). The preoperculum lies posterior to the caudal-most infraorbital and wraps around the posterodorsal margin of the maxilla. The maxilla and dentary comprise the two major tooth-bearing bones of the jaw. An acrodin cap is reported from a dentary tooth of NMS G 2002.26. 1384 ( Fig. 8 View Figure 8 ).

Jugal (ju) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 6–8 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 ): The jugal is preserved in NMS G 2002.26.1384, BMNH P.13410, and P.13407, which show it as a single bone primarily restricted to the posterior margin of the orbit. It is ventral to the dermosphenotic (NMS G 2002.26.1384, BMNH P.13410, P.13407), anterior to the preoperculum (BMNH P.13407), and posterior to the lachrymal (BMNH P.13407). Additionally, BMNH P.13407 shows the maxilla to obstruct its contribution to the upper jaw. I find no evidence that the jugal (however slight) caudally extends to dorsally contact the posteriorly expanded maxilla (BMNH P.13407, NMS G 2002.26.1384).

The jugal of S. finlayi has a rather turbulent history. It was barely reconstructed by Woodward & White (1926), interpreted as two bones by Gardiner (1963), and transformed into a single dentigerous infraorbital that contributed to the upper jaw by Gardiner & Schaeffer (1989) ( Fig. 10 View Figure 10 ). The aforementioned observations do not support any of these interpretations. The jugal is a single crescentic posterior infraorbital in all Devonian actinopterygians except for Kentuckia hlavini and Tegeolepis clarki ( Dunkle, 1964; Dunkle & Schaeffer, 1973). These taxa supposedly have four infraorbital bones like the 1963 Stegotrachelus ; however, this interpretation should be approached with scepticism.

Lachrymal (lac) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 7 View Figure 7 ): The lachrymal is the second infraorbital and situated anterior to the jugal, posterior to the premaxilla, and dorsal to the anterior ramus of the maxilla. It is best preserved in BMNH P.13407, and although fragmentary, probably does not represent two infraorbital bones as reconstructed by Gardiner (1963).

Orbit and sclerotic bones (scp) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 5 View Figure 5 , 6 View Figure 6 ): At about 28% of the head length, S. finlayi has the largest orbit of all Devonian ray-fins, although is only marginally bigger than the orbit of Tegeolepis ( Dunkle & Schaeffer, 1973) . Permitting favourable preservation, scleral ossicles can be contained within the orbit. In the examined specimens of S. finlayi they are ornamented and incompletely preserved (BMNH P.13410, NMS G 2002.26.1360). Additionally, BMNH P.13410 appears to show only one dorsal and one ventral ossicle.

Whereas the majority of Palaeozoic ray-fins have four ossicles, Gardiner (1984) reported ‘Mimia’ toombsi to have a variable number, ranging from a complete ring to four individual bones. Moreover, some specimens of Moythomasia durgaringa have two ossicles as well. Gardiner (1984) hypothesized that ontogenetic fusion of the four ossification centres may explain the variation in ossicle number. This may be accurate for S. finlayi , but their infrequent preservation makes this hypothesis difficult to test.

Preoperculum (pop) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 6–8 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 ): The preoperculum is L-shaped and divided into anterodorsal and posteroventral regions that track the expanded posterior margin of the maxilla. NMS G 2002.26.1384 confirms the preoperculum is no more dorsal than the jugal and makes no substantial contact with the dermosphenotic or operculum. The ventral region of the preoperculum is steeply angled and terminates just dorsal to the posteroventrally expanded edge of the maxilla. However, because of poor preservation, it is unclear if this ventral region contacts a quadratojugal. Ornament consists of tubercles and short anteriorly angled ridges in both the ventral and anterodorsal regions (BMNH P.13410). Evidence of the preopercular canal is visible in BMNH P.13407. The preoperculum is one of the few bones reconstructed in 1926 and 1963, although the precise details of its previously described shape are not supported by available material (NMS G 2002.26.1384, BMNH P.13407, P.13410, P.13418).

Maxilla (mx) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 6–8 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 ): The maxilla is the dominant bone of the upper jaw and bears two rows of unequal sized teeth along its entire ventral margin. It is characterized by a posteriorly expanded region that tapers as it extends below two infraorbital bones and terminates at the anterior margin of the orbit (NMS G 2002.26.1384, BMNH P.13407, P.13410). Cheirolepis is the only Devonian ray-fin whose maxillae extend beyond the anterior orbital margin ( Arratia & Cloutier, 1996, 2004). Dermal ornament is largely characterized by ridges that dip about 45° as the maxilla ventrally curves below the preoperculum (BMNH P.13410).

Similar to the preoperculum, the maxilla was described in 1926 and 1963. It does not overlap the lower jaw as intensely as either reconstruction; however, the 0.41 height: depth ratio of the original description is more accurate than the 0.35 ratio of the 1963 redescription.

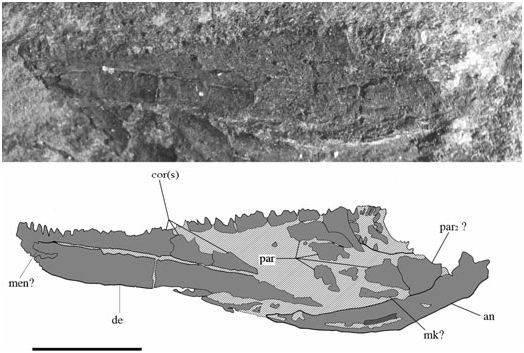

Lower jaw ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 6–8 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 , 11 View Figure 11 ): The actinopterygian lower jaw primitively includes the dentary, coronoids, prearticular, articular, and angular elements. The medial surface of the lower jaw in S. finlayi is poorly preserved, and much comparative attention has been paid to taxonomically dissimilar specimens. Considering such constraints, there are still unresolved questions surrounding the morphology of lower jaw elements in this redescription.

Like other osteichthyans, the dentary of S. finlayi is the largest bone of the lower jaw (NMS 1973.10.33, 1973.10.30, NMS G 2002.26.1384, BMNH P.13410, P.13415, P.13407, P.13418), posteroventrally overlaps a crescent-shaped articular (NMS 1973.10.30, BMNH P.13410, P.13407, P.20313; Figs 6 View Figure 6 , 7 View Figure 7 , 11 View Figure 11 ), and wraps around the ventral jaw margin to contact the coronoids medially ( Fig. 11 View Figure 11 ). Numerous small teeth reside external to the less frequent and larger medial teeth. Similar to Howqualepis , ‘Mimia’ toombsi, and Moythomasia , the large medial teeth appear to attach to the dentary and anterior coronoids, although poor preservation makes this difficult to recognize (BMNH P.20313; Gardiner, 1984; Long, 1988). The posterior margins of the second (?) and third (?) coronoids are broken; thus it is unclear how many coronoids are present and where prearticular–coronoid contact begins. The prearticular appears limited to the posteromedial margin of the lower jaw. However, it is fragmentary and therefore uncertain whether S. finlayi has one prearticular (like ‘Mimia’ toombsi and Howqualepis ) or two prearticulars (like Moythomasia ; Gardiner, 1984; Long, 1988). The articular region of Meckel’s cartilage appears ossified, but poor preservation makes proper recognition of an articular and surangular difficult.

Palate

The palate is not well preserved in any known specimen of S. finlayi .

Operculogular series

The operculogular series consists of the dermohyal, accessory operculum, operculum, suboperculum, gulars, and branchiostegal rays. The accessory operculum, dermohyal, and 12 branchiostegals (per side) are not present in the 1926 or 1963 reconstructions of S. finlayi .

Dermohyal (dhy) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 6 View Figure 6 , 8 View Figure 8 ): This small bone is located immediately dorsal to where the ventral and anterodorsal regions of the preoperculum differentiate. It is situated anterior and anterodorsal to the operculum and accessory operculum, respectively. NMS G 2002.26.1384 ( Fig. 8 View Figure 8 ) affirms that a dermohyal sits dorsal to the preoperculum, but extends no higher than the jugal (NMS G 2002.26.1384). Although its rounded anterodorsal edge almost contacts the dermosphenotic, NMS G 2002.26.1384 shows no evidence of close dermohyal–supratemporal proximity. Additionally, although the largest specimen shows that the anterolateral surface of the supratemporal lies adjacent to the dermosphenotic [NMS 1973.10.35.(P.); Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ], some specimens [BMNH P.13410, P.13407; Figs 6 View Figure 6 , 7 View Figure 7 ] depict a small lateral space between the dermosphenotic and operculum into which the dermohyal could (in principle) extend. It appears post-mortem compression has separated the margin of contact between the dermosphenotic and skull roofing bones in these specimens. Thus, this apparent lateral gap may be an artefact of preservation.

The dermohyal was not reconstructed by Woodward & White (1926) or by Gardiner (1963) but was included by Gardiner & Schaeffer in the 1989 republication of Gardiner’s original reconstruction ( Fig. 10 View Figure 10 ). The 1989 dermohyal appears to stem from specimen BMNH P.13410 ( Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ), which shows a series of vertically orientated splint-like dermal ridges just anterior to the operculum. To reconstruct the dermohyal and account for this ridging, Gardiner & Schaeffer (1989) wedged a V-shaped bone between the preoperculum and operculum. The preoperculum retained its original high profile whereas the introduced dermohyal now sat ventral to the supratemporal. Although the presence of a dermohyal is confirmed, this reconstruction is not supported by available data.

Accessory operculum (aop) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 6–8 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 ): The accessory operculum is a small, wedge-shaped, relatively inconspicuous bone surrounded by the preoperculum, dermohyal, operculum, and suboperculum (NMS G 2002.26.1384, BMNH P.13410, P.13407). Amongst Devonian ray-fins, it is also present in Cheirolepis , Moythomasia nitida , Krasnoyarichthys , and Donnrosenia ( Jessen, 1968; Arratia & Cloutier, 1996; Prokofiev, 2002; Long et al., 2008). One might suppose the accessory operculum in this redescription be interpreted as the ascending process of the suboperculum. However, although this hypothesis may appear plausible, it is important to discuss the observations and implications of such an alternative.

The (interpreted) accessory operculum in S. finlayi is very similar to that of Moythomasia nitida . In both taxa, they are less than half the length of the operculum, situated anterior to the suboperculum along its flat anterodorsal margin, and minimally overlap the dermohyal dorsally. By contrast, although the accessory operculum of Cheirolepis trailli sits anterodorsal to the suboperculum (the condition seen in M. nitida and S. finlayi ), it also extends farther anterior than the accessory opercula in either of these taxa (see Arratia & Cloutier, 2004, fig. 5, for accessory opercular variation in Cheirolepis ). Moreover, amongst Devonian ray-fins, the ascending process of the suboperculum is pronounced in Howqualepis , ‘Mimia’ toombsi, Osorioichthys , Limnomis , and Donnrosenia , none of which extend as far as the straightmargined, wedge-shaped accessory opercula of M. nitida , Krasnoyarichthys , Cheirolepis spp. , or S. finlayi . The ascending processes in such taxa consistently terminate short of the known anterior limit of accessory opercula in all known Devonian actinopterygians. This contribution considers the presence of an accessory operculum in S. finlayi the more likely interpretation.

Operculum (op) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 6–8 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 ): The operculum is a large rectangular bone just below the supratemporal that is ventrally convex and about twice as deep as wide [NMS 1973.10.35.(P.), BMNH P.13407, P.13410, NMS G 2002.26.1384]. It is surrounded by the accessory operculum (NMS G 2002.26.1384, BMNH P.13410, P.13407) dermohyal (NMS G 2002.26.1384), suboperculum [NMS G 2002.26.1384, BMNH P.13410, P.13407, NMS 1973.10.35.(P.)], cleithrum (NMS G 2002.26.1384), supracleithrum (BMNH P.13407, NMS G 2002.26.1384), supratemporal (BMNH P.13407, P.13410, NMS G 2002.26.1384), and presupracleithrum (BMNH P.13407). In addition, although dermosphenotic–operculum contact is not directly observable, the straight terminal end of the dermosphenotic [NMS 1973.10.35.(P.)] lies adjacent to the kinked lateral edge of the supratemporal, and just anterior to where supratemporal–operculum contact would begin [BMNH P.13407, NMS 1973.10.35.(P.); Fig. 4 View Figure 4 ]. Thus, it appears that the posterior margin of the dermosphenotic could contact the anterior tip of the operculum, which would fit into the ‘pocket’ formed by the dermosphenotic and supratemporal. Dermal ornament consists of rostrocaudally directed ridges that dip about 10° below the rostrocaudal axis and emanate from the unornamented anterodorsal tip of the operculum (BMNH P.13407, P.13410; Figs 6 View Figure 6 , 7 View Figure 7 ).

Suboperculum, gulars, and branchiostegal rays (sop, lg, br) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 6–8 View Figure 6 View Figure 7 View Figure 8 ): Subquadrate and one third as deep as the operculum, the suboperculum lies dorsal to the branchiostegal rays and posteroventral to the accessory operculum [NMS G 2002.26.1384, BMNH P.13410, P.13407, NMS 1973.10.35.(P.)]. There are 12 branchiostegals per side (BMNH P.13410), similar to Cheirolepis schultzei , Moythomasia , and ‘Mimia’ toombsi. Rays 11 and 12 are also seen in BMNH P.20313, P.13407 and NMS G 2002.26.1384 ( Figs 8 View Figure 8 , 9 View Figure 9 ; Gardiner, 1984; Arratia & Cloutier, 2004). Just anterior to the branchiostegals, the lateral gular constitutes the last visible element of the operculogular series (BMNH P.13410). It is about one quarter to two thirds of the length of the dentary, about as long as three branchiostegal rays, and largely dominated by rostrocaudally directed dermal ridges (BMNH P.13410).

With the exception of Cheirolepis canadensis and Donnrosenia schaefferi ( Arratia & Cloutier, 1996; Long et al., 2008), no known Devonian ray-fin has fewer than 12 branchiostegal rays; however, S. finlayi has twice been reconstructed to have six ( Woodward & White, 1926; Gardiner, 1963). It appears that these previous descriptions combine pairs of branchiostegals to halve the actual total seen in BMNH P.13410.

Pectoral girdle

The pectoral girdle is typical of Palaeozoic ray-fins, comprising the post-temporal, presupracleithrum, supracleithrum, postcleithrum, cleithrum, and clavicle – a pattern similar to the primitive condition among sarcopterygians as well ( Rosen et al., 1981). The presence of endoskeletal elements and an interclavicle is unknown. The postcleithrum and presupracleithrum are newly described.

Post-temporal (pt) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 5 View Figure 5 , 6 View Figure 6 ): Paired and present in NMS G 2002.26.1360 and BMNH P.13410, the posttemporal sits immediately dorsal to the supracleithrum and presupracleithrum. It is situated behind the straight posterior margin of the extrascapular and minimally abuts the adjacent post-temporal. Dermal ridging consists of marginally curved linear bands that enclose a striated core of ornament parallel with the main body axis. Unlike Gardiner’s 1963 reconstruction, the post-temporal lacks a convex anterior margin.

Presupracleithrum (pscl) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 6 View Figure 6 , 8 View Figure 8 ): The presupracleithrum is a small bone surrounded by the supratemporal, post-temporal, operculum, and extrascapular (BMNH P.13410; Fig. 6 View Figure 6 ). Similar to Moythomasia , it posteriorly borders the supratemporal to sit between the operculum and extrascapular ( Jessen, 1968; Gardiner, 1984). Dermal ornament consists of horizontal ridges that bend ventrally along its posterior margin. The presupracleithrum was not described in 1926 or 1963.

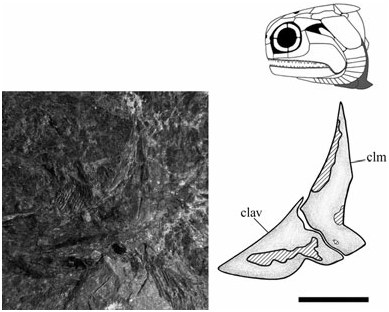

Cleithrum (clm) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 12 View Figure 12 ): The cleithrum is typically ‘palaeoniscoid’ in shape with a concave anterior margin that borders the suboperculum and branchiostegals [NMS G 2002.26.1360, 2002.26.1384, NMS 1973.10.30.(C.)]. The broadest part is immediately anterior to the pectoral embayment at about one quarter of its total height [NMS 1973.10.30.(C.), NMS G 2002.26.1360]. Vertical ridges dominate at midheight, although ventrally change to a convoluted network of ornament where the clavicle overlaps the cleithrum [NMS G 2002.26.1360, NMS 1973.10.30.(C.)]. The pectoral embayment is deeper than previously reconstructed; similar in depth to ‘Mimia’ toombsi and Moythomasia , but not as deep as Howqualepis or Cheirolepis ( Jessen, 1968; Gardiner, 1984; Long, 1988; Arratia & Cloutier, 2004).

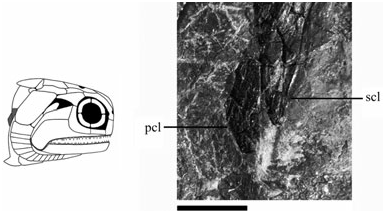

Supracleithrum (scl) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 8 View Figure 8 , 13 View Figure 13 ): The supracleithrum is dorsally broad, with a ventral margin that tapers to a point and resides posterior to the dorsal end of the cleithrum (NMS G 2002.26.1384, 2002.26.1360). This relationship has been previously described by Woodward & White (1926) and Gardiner (1963), and is also a primitive condition among osteichthyans ( Rosen et al., 1981). Posterior to the operculum, the supracleithrum sits ventral to the post-temporal and presupracleithrum (BMNH P.13410); a pattern also present in ‘Mimia’ toombsi, Moythomasia , Howqualepis , and Cuneognathus ( Jessen, 1968; Gardiner, 1984; Long, 1988; Friedman & Blom, 2006). Dermal ridges anterodorsally slope about 45° below the rostrocaudal axis (BMNH P.13410) but vertically align as they descend the tapering ventral blade (NMS G 2002.26.1360).

Postcleithrum (pcl) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 13 View Figure 13 ): The postcleithrum is a small, broad-based triangular-shaped bone positioned laterally on the flank immediately posterior to the supracleithrum and cleithrum (NMS G 2002.26.1360, 2002.26.1384). Ornament is similar to the ventral blade of the supracleithrum, with nearly vertical ridges spanning its entire length (NMS G 2002.26.1360). In these ways it is morphologically distinguishable from the surrounding, vertically narrow, rhomboid flank scales. Gardiner (1984: 374) explicitly states its absence in S. finlayi ; however, a postcleithrum is fairly common in early ray-fins, known in ‘Mimia’ toombsi, Moythomasia , Osorioichthys , Howqualepis , and Donnrosenia ( Jessen, 1968; Gardiner, 1984; Long, 1988; Taverne, 1997; Long et al., 2008), several basal sarcoptergian groups ( Arratia & Cloutier, 1996; Janvier, 1996; Schultze & Cumbaa, 2001), and a possible symplesiomorphy for crown-group osteichthyans as a whole. Although it is important to note that the postcleithrum of most sarcopterygians is unornamented, it is considered subdermal in life, and consequently referred to as the anocleithrum ( Rosen et al., 1981). Alternatively, certain taxa like ‘ Mimia ’ toombsi are argued to show the convergent history of the postcleithrum as a co-opted scale, which in this taxon still retains a modified dorsal peg for attachment to the supracleithrum ( Gardiner, 1984: 374).

Clavicle (clav) ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 12 View Figure 12 ): The clavicle is a relatively long bone with a convex face that tapers to an apex at its anterior margin [NMS G 2002.26.1360, 2002.26.1361, NMS 1973.10.30.(C.)]. Its dorsal

| NMS |

National Museum of Scotland - Natural Sciences |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.