Prosorhochmus belizeanus, Maslakova & Norenburg, 2008

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00222930801995747 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/039CF65B-546E-FF90-1A97-1FC0FD1FF905 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Prosorhochmus belizeanus |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Prosorhochmus belizeanus , sp. nov.

( Figures 1H View Figure 1 , 2–6 View Figure 2 View Figure 3 View Figure 4 View Figure 5 View Figure 6 , 7I View Figure 7 ; Tables 1–4)

Etymology

The species is named after the country of its type locality – Belize.

Type material

Serial histological sections of the holotype (mature female, USNM 1020503 View Materials ) and six paratypes ( USNM 1020501 View Materials , 1020502 View Materials , 1020504-07 View Materials ) are deposited in the collection of US National Museum of Natural History , Smithsonian Institution. Specimens USNM 1020502-07 View Materials were collected by JLN and SAM from the type locality at Carrie Bow Cay, Belize in February 2000 . Specimen USNM 1020501 View Materials was collected by JLN from Lake Worth Inlet near West Palm Beach, FL, USA in February 1998 .

Material examined

Prosorhochmus belizeanus sp. nov. USNM 1020501-1020507. Additional material: Prosorhochmus sp. 137 USNM 1020648 (coll. JLN, Peanut Island, near West Palm Beach, FL, USA).

Diagnosis

Prosorhochmus belizeanus sp. nov. possesses a unique apomorphy of acidophilic cephalic glands forming a compact cluster in the precerebral region ( Figures 4C–D, G–H, K View Figure 4 ). Additionally, it differs from P. claparedii , P. adriaticus , P. americanus and P. chafarinensis in being gonochoric and oviparous ( Figures 1H View Figure 1 , 4E View Figure 4 , 5F View Figure 5 , 6F View Figure 6 ) and from P. americanus in lacking well-developed purple cephalic glands (compare Figures 4G View Figure 4 and 9A View Figure 9 ). Central stylet (S) 185–250 Mm long, average 209.1 Mm, significantly different (longer) from that of Prosorhochmus chafarinensis , Prosorhochmus nelsoni and Prosorhochmus claparedii (p50.05); basis (B) truncated, 225–375 Mm long, average 295 Mm, significantly different from that of P. chafarinensis , P. nelsoni and P. claparedii (p 50.05); central stylet to basis (S/B) ratio is 0.60–0.83, average 0.72, significantly different from that of P. chafarinensis , but not from that of P. claparedii or P. nelsoni (p 50.05) (see Table 2).

Habitat, type locality and distribution

The type locality is Carrie Bow Cay, site of the Smithsonian Institution’s Caribbean Coral Reef Ecosystems Station, located 18 km offshore on the barrier reef in Belize (16 ° 489 N, 88 ° 059 W). The specimens were obtained by breaking coral rubble exposed during low tide on the reef flat on the SE side of the island. A single specimen was collected from a bivalve–vermetid community encrusting a concrete piling at Lake Worth Inlet near West Palm Beach, Florida.

Description

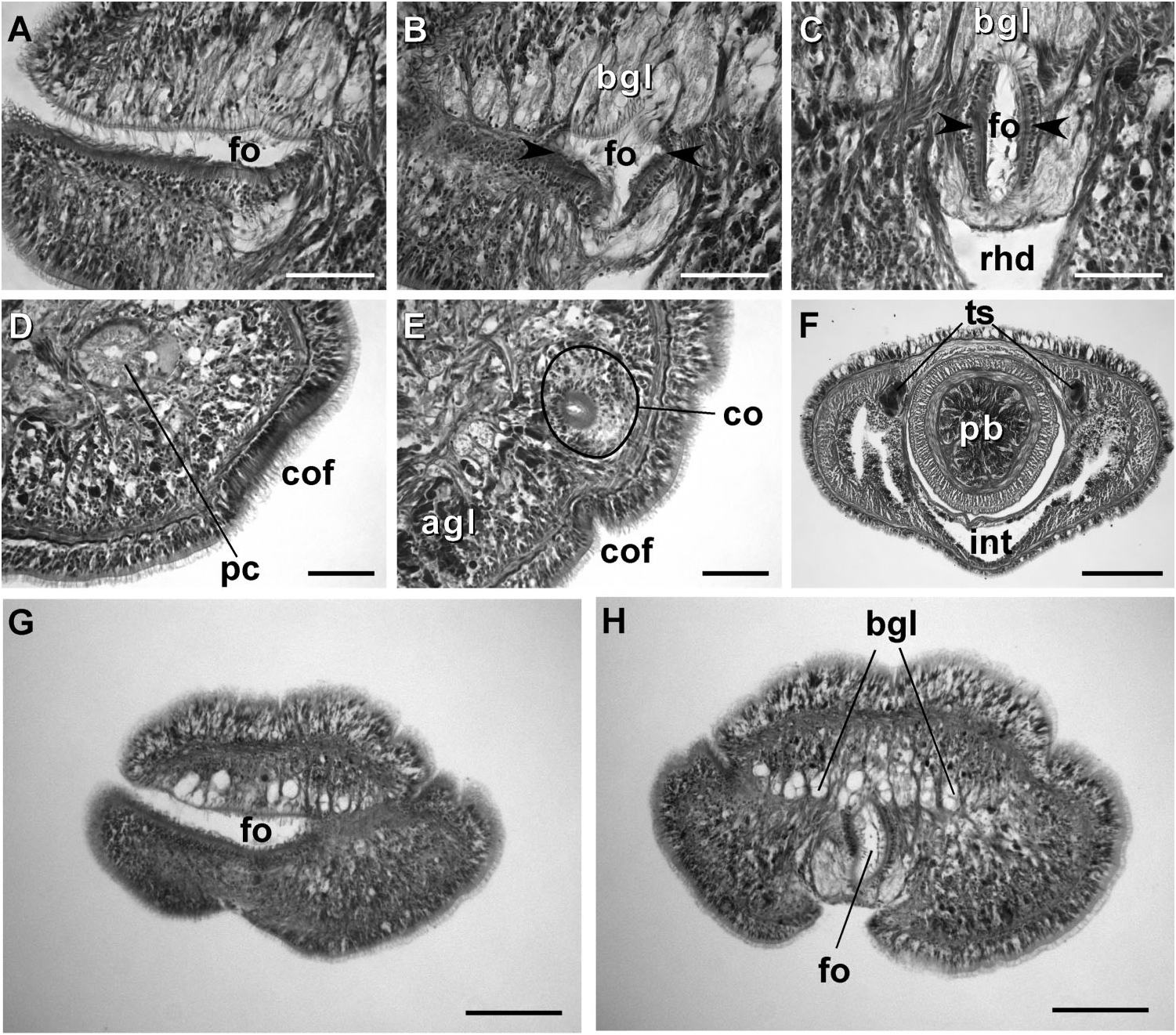

External appearance. Prosorhochmus belizeanus sp. nov. is relatively small, with maximum recorded length of reproductive specimens 35 mm and width 1.0 mm. The colour in life is yellowish-rosy, orange-yellow or salmon, head and ventral side slightly paler than the rest of the body. In some specimens narrow bands or specks of dark brown pigment extend posteriorly along the edges of lighter rhynchocoel, fading out toward the anterior end ( Figure 1H View Figure 1 ). The body is slender and compact, dorso-ventrally flattened, wider at the anterior end, gradually tapering toward the posterior to end in a bluntly rounded tip. The head is spatulate in shape and wider than the adjacent body region, with a characteristic vertical anterior notch giving it a distinct bifid appearance. A dorsal horizontal epidermal fold anterior to the eyes separates two ventral apical lobes of the head from a median dorsal lobe, creating the appearance of a ‘‘smile’’ ( Figures 1H View Figure 1 , 2A– B View Figure 2 ), characteristic of the genus. The four reddish-brown eyes are situated in front of the brain; the anterior pair is slightly larger than the posterior. The distance between the eyes of the anterior pair and the posterior pair is larger than between the two pairs. The rudimentary cerebral organ furrows, also referred to as the anterior cephalic grooves, appear as a pair of inconspicuous latero-ventral, whitish, semi-circular grooves approximately at the level of the anterior pair of eyes, reaching slightly over onto the dorsal side ( Figures 2A–B View Figure 2 ). The shallow posterior cephalic furrow is indistinct and forms a dorsal, posteriorly directed ‘‘V’’ immediately behind the brain and a ventral, incomplete anteriorly directed ‘‘V’’ immediately anterior to the brain ( Figures 2A–B View Figure 2 ). The rhynchopore is subterminal.

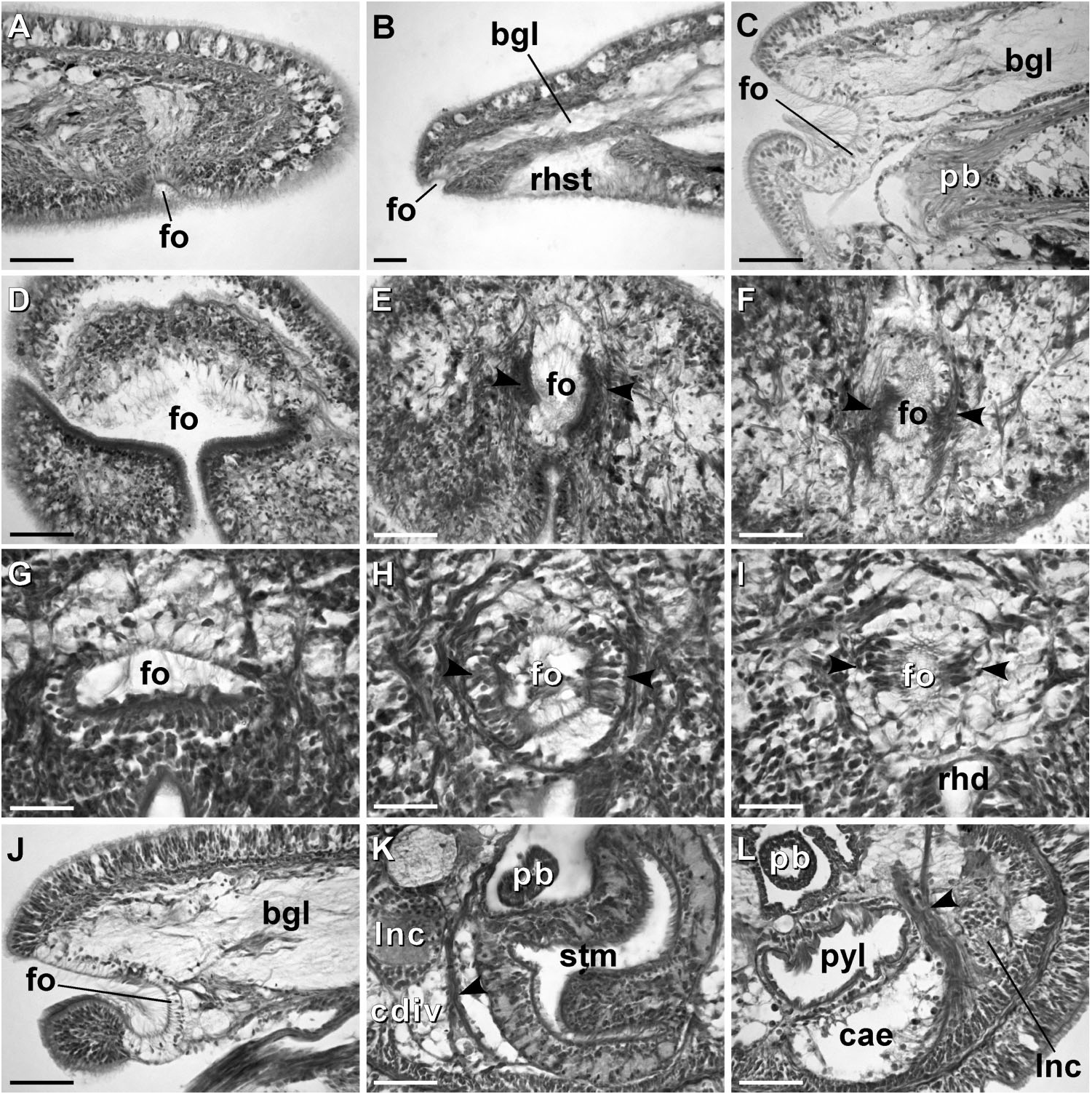

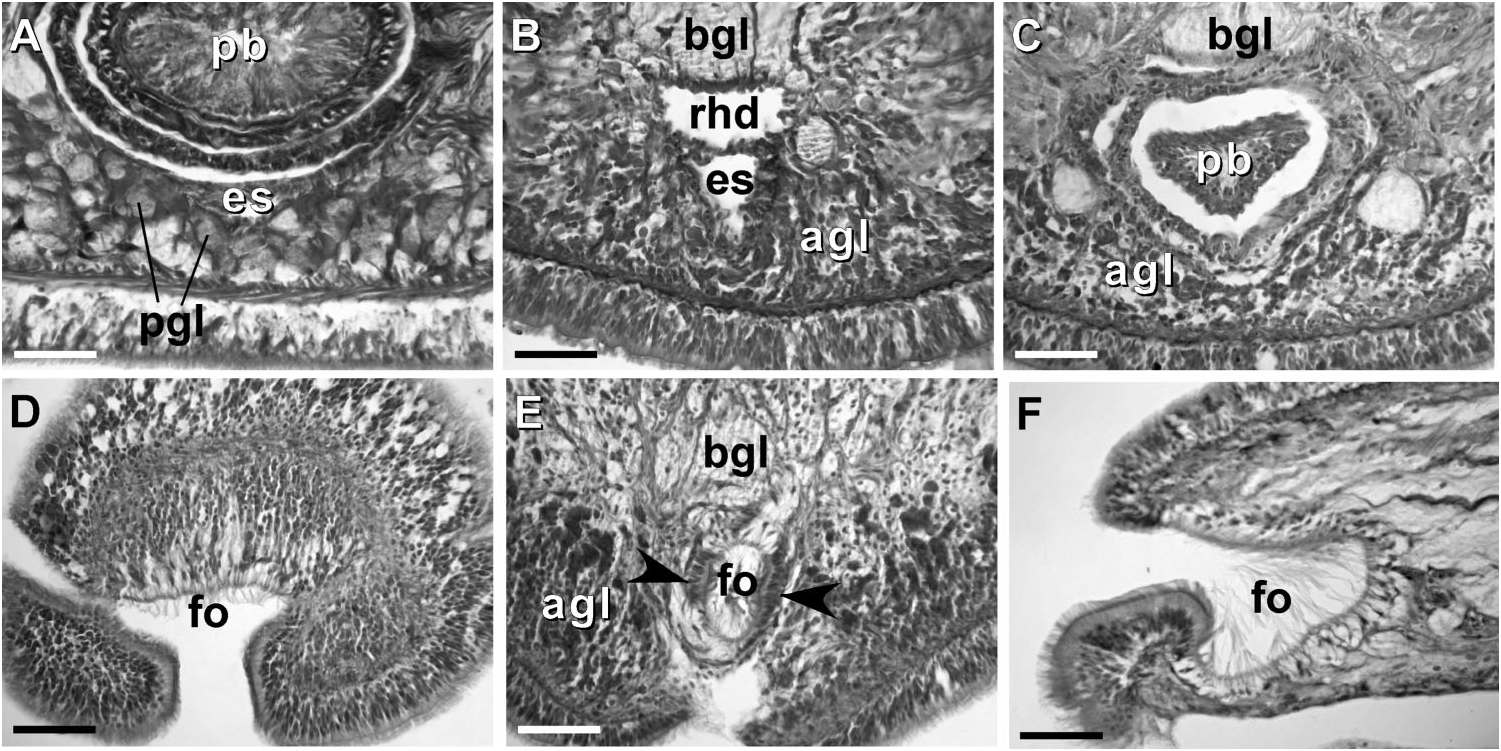

Body wall, musculature and parenchyma. Epidermis is of typical hoplonemertean structure ( Figure 4A View Figure 4 ). Dermis is represented by a thin layer of extracellular matrix. Body-wall musculature consists of an outer circular layer and an inner longitudinal layer. Diagonal (oblique) muscle fibres situated between the circular and longitudinal musculature of the body wall form a thin but distinct layer. This layer is best visualized in longitudinal sections ( Figure 4B View Figure 4 ). The precerebral septum is of split ( Kirsteuer 1974) or mixed type ( Chernyshev 2002). It is formed by individual muscle fibres emerging from the body-wall longitudinal musculature at several levels. Behind the brain, separate bundles of oblique fibres diverge from the inner margins of the longitudinal muscle layer and lead forward toward the proboscis insertion. Here the oblique fibres are joined by additional (radial) fibres, which turn inward from the main layer ( Figure 4C, D View Figure 4 ). A few individual fibres from the inner portion of the longitudinal musculature continue into the head as cephalic retractors. Dorsoventral muscles are strongly developed between the gonads and intestinal diverticula ( Figure 4E View Figure 4 ). Anteriorly, thick dorso-ventral muscles are found between the lateral pouches of the caecum, lobes of the mucus cephalic glands and the lateral nerve cords ( Figures 4F View Figure 4 , 6D, E View Figure 6 ). Muscle fibres oriented dorso-ventrally, obliquely and horizontally are abundant in the precerebral region ( Figure 4G View Figure 4 ). The musculature associated with the foregut, in the literature often referred to as ‘‘splanchnic musculature’’, is very well developed and is continuous with the fibres surrounding the rhynchodeum. A longitudinal muscle layer surrounds the oesophagus from the point of its separation from the rhynchodeum to the brain region ( Figure 4H View Figure 4 ). At this point, oesophageal muscles become surrounded by additional longitudinal fibres originating at the proboscis insertion ( Figure 4I View Figure 4 ). These muscles continue as a thin layer surrounding the stomach and are particularly apparent between its folds ( Figure 4J View Figure 4 ). The amorphous extracellular matrix, of the so-called ‘‘parenchyma’’, is scarce and otherwise unremarkable.

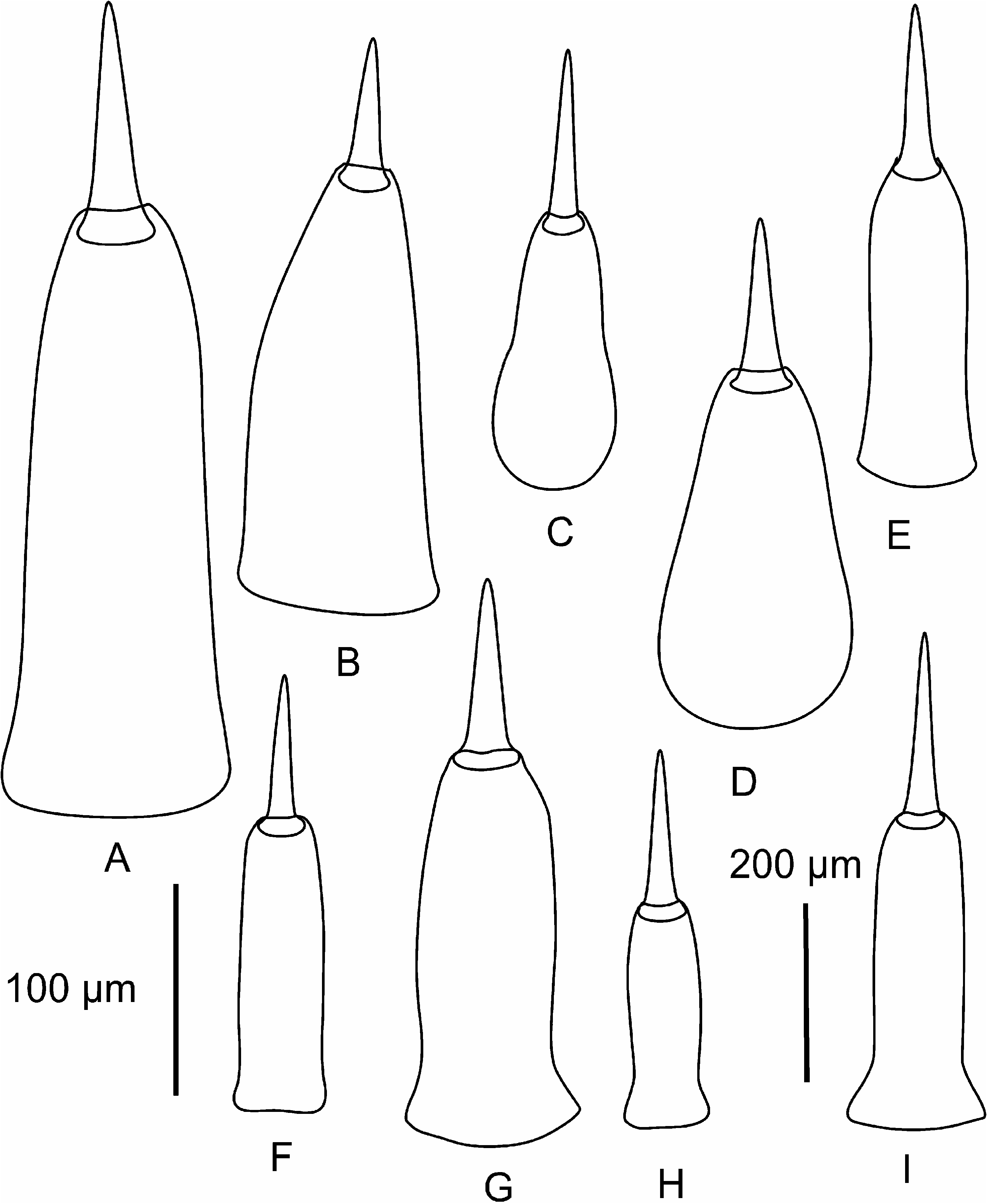

Proboscis apparatus. The proboscis pore opens terminally. It leads into a short, thinwalled rhynchodeum. Rhynchodeal epithelium comprises squamous cells with small elongated nuclei ( Figure 4K View Figure 4 ). Just anterior to the proboscis insertion, it is comprised of cells with acidophilic cytoplasm and large nuclei ( Figure 4L View Figure 4 ). It was not possible to determine with light microscopy whether rhynchodeal epithelial cells bear cilia or not. The rhynchodeal musculature is rather well developed and comprises both longitudinal and circular muscle fibres. There is no localized concentration of circular muscle fibres representing a distinct rhynchodeal sphincter. The rhynchocoel reaches almost to the posterior end of the body. Its wall is of typical distromatonemertean ( Thollesson and Norenburg 2003) structure i.e. contains separate outer circular and inner longitudinal muscle layers ( Figure 3A View Figure 3 ). The thickness of the layers changes dramatically with the state of contraction of the animal. The proboscis is thin, longer than the body, somewhat translucent and whitish to dull cream. Immediately after proboscis insertion its wall consists of a thin non-glandular epithelium, a thin layer of extracellular matrix, an outer circular muscle layer, a longitudinal muscle layer divided into two concentric layers by the neural sheath with distinct proboscis nerves, a delicate layer of inner circular muscles, and a thin endothelium ( Figure 3B View Figure 3 ). Further posterior, the proboscis wall comprises all the same layers except for the proboscideal epithelium, which is thick, glandular and arranged into conical papillae ( Figures 3C, D View Figure 3 ). The neural sheath bears 11–14 proboscis nerves ( Figure 3C View Figure 3 ). The proboscis armature consists of a central stylet, mounted on a characteristically truncated basis ( Figure 7I View Figure 7 ) and two pouches each containing 1–3 accessory stylets. The length of the central stylet (S) ranges from 185 to 250 Mm (average 209.1 Mm), basis length (B) ranges from 225 to 375 Mm, (average 295 Mm) and S/B ratio ranges from 0.60 to 0.83 (0.71 on average), see Tables 2–3. The wall of the posterior chamber of the proboscis consists of glandular epithelium, outer longitudinal muscle layer, inner circular muscle layer and a delicate endothelium ( Figure 3E View Figure 3 ). We did not observe distinct nerve supply in the longitudinal muscle layer of the posterior proboscis of P. belizeanus sp. nov.

Alimentary canal. The oesophagus opens into the rhynchodeum in front of the precerebral septum. It is enclosed by longitudinal muscle fibres ( Figures 4H–I View Figure 4 ), which are confluent with the rhynchodeal musculature and continue posteriorly as the musculature of the stomach. The posterior part of the oesophagus is ciliated and lacks acidophilic or basophilic glands ( Figure 4I View Figure 4 ). The stomach is of typical hoplonemertean structure with densely ciliated, deeply folded epithelium, containing numerous basophilic and acidophilic glands ( Figure 4J View Figure 4 ). Specimens from Belize lack a ventral posterior stomach ‘‘pouch’’, while the only specimen from Florida (USNM 1020501) possesses a single ‘‘pouch’’ about 80 Mm long ( Figure 4F View Figure 4 ). We do not attribute any taxonomic significance to the presence or absence of such ‘‘pouches’’, as they are likely a result of folding of the voluminous stomach. The intestinal caecum is well developed and may be anteriorly bifid: divided portion up to 100 Mm long, reaching the posterior portion of the dorsal cerebral ganglia. The caecum bears numerous lateral diverticula throughout its length. These and intestinal diverticula are lobed.

Blood system. The blood system is of usual hoplonemertean type. A cephalic suprarhynchodeal loop crosses just behind the posterior chamber of the frontal organ and continues posteriorly as the body’s paired lateral vessels. The middorsal blood vessel originates near the ventral cerebral commissure and immediately penetrates the rhynchocoel floor to form a single vascular plug. The wall of the vascular plug consists of thickened endothelium of the blood vessel, a thin layer of extracellular matrix and a modified rhynchocoel endothelium ( Figure 3H View Figure 3 ). We did not observe any transverse connectives linking mid-dorsal and lateral blood vessels in the intestinal region. The blood vessels are thin-walled with a well-defined lumen and irregular thickenings of the wall. Apparently, during contraction of the blood vessels the latter may appear as ‘‘pouches’’ or ‘‘valves’’ ( Figures 3F–G View Figure 3 ).

Nervous system. As is typical for nemerteans, the brain consists of two ventral and two dorsal ganglia, joined by ventral (subrhynchocoelic) and dorsal (suprarhynchocoelic) commissures, respectively. The smaller dorsal ganglia are more widely separated than the ventral. A thin, but distinct outer neurilemma encloses the brain as a whole, but there is no inner neurilemma dividing the fibrous and ganglionic tissues. There are no neurochord cells in the brain ganglia and no neurochords in the lateral nerve cords. The lateral nerve cords contain a single fibrous core throughout their length. The so-called ‘‘upper’’ nerve is present – a bundle of nerve fibres in the dorsal part of the fibrous core of the lateral nerve cord, distinguished by their lighter colour, which we observed in all other species of Prosorhochmus ( Figures 3I, K View Figure 3 ). The difference between this upper nerve and a real accessory nerve is that the upper nerve is never separated from the main fibrous core by cell bodies, and it is derived from the ventral cerebral ganglion, as opposed to the dorsal cerebral ganglion. As observed in most monostiliferans studied in the last three decades, each lateral nerve cord contains a single delicate muscle bundle (several fibres thick) running within or adjacent to the fibrous core ( Figure 3I View Figure 3 ). In addition, there are several less conspicuous muscle fibres running along the inner lateral side of the fibrous core. Muscle fibres associated with the lateral nerve cords can usually be traced to their extracerebral origin near the proboscis insertion. Cephalic nerves lead anteriorly from the brain ganglia to supply various structures of the head. Two stout nerves originating from the ventral ganglia innervate paired cerebral sensory organs.

Eyes. The four eyes are well-developed pigment cups. The eyes of the anterior pair are slightly larger than the posterior. The pigment cups of the anterior pair are facing antero-laterally, while those of the posterior pair are directed posterolaterally ( Figure 3J View Figure 3 ).

Frontal organ. The frontal organ consists of a ciliated canal 50 – 85 Mm long, lined by a regionally differentiated epithelium ( Figures 4C–D View Figure 4 , 5A–C, G, H View Figure 5 ). The anterior portion of the canal is often triangular in cross-section, becoming rounded or oval toward the posterior end. Anteriorly, the ventral wall of the frontal organ comprises strongly acidophilic epithelium, clad in densely-arranged short cilia, which soon divides to run on lateral borders of the canal. The portions of the canal, through which the basophilic mucus cephalic glands discharge, have vacuolated appearance and bear much longer, sparsely distributed cilia. There do not appear to be subepidermal acidophilic glands associated with the acidophilic epidermis of the frontal organ. It seems that the acidophilic appearance comes from the densely arranged elongated nuclei of the ciliated cells.

Cephalic glands. Cephalic glands are extremely well developed. As in other members of the genus, they include three distinct types: strongly vacuolated basophilic lobules (mucus glands), coarsely granular proteinaceous gland cells staining golden-yellow to brown with Mallory trichrome or orange with Crandall’s method (orange-G glands), and finely granular proteinaceous acidophilic cells, staining pink to red with Mallory or Crandall’s technique (acidophilic or red glands).

Basophilic (mucus) glands are well developed and open through the dorsal, ventral and posterior epithelium of the frontal organ ( Figures 4C–D View Figure 4 , 5B–C View Figure 5 ). Dorsal lobes reach their maximum development in the cerebral region and reach as far back as the anterior pyloric region, while the two ventro-lateral lobes running parallel to the oesophagus reach the anterior end of stomach.

Red acidophilic glands are well developed but restricted to the precerebral region. At the level of the frontal organ they are most abundant dorsally, in some individuals forming almost a continuous layer between the dorsal basophilic lobules and the longitudinal musculature of the body wall. Numerous red gland cells are also scattered ventrally and laterally on both sides of the rhynchodeum. Necks of the red glands reach to the epidermis and open via numerous pores dorsally, ventrally and laterally. Further back, at the level of the cerebral organs, dorsal red glands decrease in numbers, while the ventral red glands become much more abundant, and form a dense cluster below the oesophagus, reaching their maximum abundance in front of the precerebral septum ( Figures 4C–D, G, H, K View Figure 4 , 6A–B View Figure 6 ). A few isolated red gland cells persist after the septum, mostly in the dorsal region, interspersed with the orange-G and mucus glands.

Orange-G glands are very strongly developed, particularly in the cerebral and foregut regions ( Figures 3K–L View Figure 3 , 4G View Figure 4 , 6A–D View Figure 6 ). They open via improvised ducts in the dorsal epithelium and can be found as far back as the end of the rhynchocoel. On series of transverse sections, orange-G gland cell bodies first appear near the anterior pair of eyes, on both sides of the rhynchodeum, although their glandular necks can be traced all the way into the anterior-most tip of the head, where they lie interspersed with the cell bodies of the red glands and open via numerous pores just above the frontal organ. Orange-G glands gradually increase in number further back and reach their maximum abundance immediately behind the brain, where they form dense dorso-lateral clusters on each side of the rhynchocoel adjacent to the nerve cords and nephridial tubules ( Figure 3K View Figure 3 ). Near the end of the pylorus, orange-G glands become restricted to the two narrow dorso-lateral strips – one on each side of the rhynchocoel between the diverticula of the gut and the longitudinal body wall musculature ( Figure 6F View Figure 6 ).

Cerebral organs. Small paired cerebral organs are situated almost entirely in front of the brain between the anterior and posterior pairs of eyes. The posterior portion of the cerebral organs slightly overlaps with the anterior portion of the brain. Each organ opens at the level of the anterior pair of eyes into a reduced ventro-lateral cerebral organ furrow, which is nothing more than a shallow ventro-lateral crescentshaped groove ( Figures 1C View Figure 1 , 2B View Figure 2 ) lined with a strongly acidophilic epithelium ( Figures 5D–E View Figure 5 ). The cerebral organ canals are not branched. The posterior portion of the cerebral organ is a glandular lobe with finely granular acidophilic secretion ( Figure 5E View Figure 5 ).

Excretory system. The protonephridial system extends from the dorsal brain ganglia to the anterior pyloric region, most of it immediately dorsal to the lateral nerve cords and the lateral blood vessels. Ciliated nephridial tubules are thick-walled and not regionally specialized. Paired nephridia open dorso-laterally immediately posterior to the brain via two nephridiopores - one on each side ( Figures 3L View Figure 3 , 6E View Figure 6 ). Small and hardly noticeable mononucleate flame cells are found embedded in the extracellular matrix in the vicinity of the lateral blood vessels.

Reproductive system and life history: Prosorhochmus belizeanus sp. nov. is gonochoric. Reproductive males and females were observed in February in Belize and Florida. As in most other nemerteans, gonads alternate with the lobes of intestinal diverticula ( Figures 1H View Figure 1 , 4E View Figure 4 , 5F View Figure 5 , 6F View Figure 6 ). Similar to Prosorhochmus nelsoni , up to 20–30 mature oocytes can be observed within the same ovary ( Figure 6F View Figure 6 ), indicative of oviparity. Pinkish oocytes can be readily observed through the body wall of mature females ( Figure 1H View Figure 1 ).

Remarks

Characters, such as bifid anterior cephalic margin with the ‘‘prosorhochmid smile’’, truncated stylet basis, well-developed frontal organ with laterally differentiated epithelium, well-developed cephalic glands, combining mucus and at least two kinds of proteinaceous components (staining pinkish-red and golden-orange with Mallory trichrome) and protonephridial system with mononucleate flame cells without distinct support bars, thick-walled excretory tubules and a single pair of nephridiopores place this species in the genus Prosorhochmus . Sequence divergence between Prosorhochmus belizeanus sp. nov. and its closest congener Prosorhochmus nelsoni is 7.7% for 16S rDNA and 9.1% for COI, which is comparable to the sequence divergence from the European (viviparous and hermaphroditic) species of Prosorhochmus (Table IV). One additional Prosorhochmus specimen, a female with numerous mature oocytes in each ovary, histologically indistinguishable from the P. belizeanus sp. nov., but much larger than all other known specimens of this species (50 mm long and 1–1.5 mm wide), was collected by JLN in March, 1983 from a split Coquina rock at the low tide near Peanut Island, Fort Worth Inlet, Florida ( Prosorhochmus sp. 137). Unfortunately, the specimen was collected without its proboscis. Thus, stylet characteristics could not be evaluated. Material for molecular analysis is not available from this specimen to determine with certainty whether it belongs to P. belizeanus sp. nov. Serial histological sections of this specimen are stored at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C. (USNM 1020648). Repeated efforts to recollect similar specimens from Florida in subsequent years were unsuccessful.

Prosorhochmus chafarinensis Frutos et al., 1998 View in CoL

( Figures 1B–C, 1F View Figure 1 , 7A–B, 7F View Figure 7 , 9C–F View Figure 9 ; Tables 1–4) Prosorhochmus chafarinensis View in CoL ( Frutos et al. 1998; Maslakova et al. 2005)

Etymology

The species is named after the place of discovery, the Spanish Chafarinas Islands off the coast of Morocco (western Mediterranean).

Type material

Holotype and two paratypes MNHM 5.01 View Materials /1. Isabel II Island, Chafarinas Islands, Spain.

Material examined

Prosorhochmus chafarinensis Frutos, 1998 View in CoL . Holotype and two paratypes MNHM 5.01 View Materials /1. Additional speciemens colleced by SAM in Savudrija and Zambratija, Croatia, Adriatic Sea and identified as P. cf. chafarinensis: USNM View in CoL 1020514 a series of transverse sections of anterior end, a series of longitudinal frontal sections of midbody and a series of longitudinal saggital sections of the posterior; USNM 1020515 View Materials and 1020517 two series of longitudinal frontal sections of anterior and posterior; USNM 1020516 View Materials a series of longitudinal saggital sections of anterior and posterior; USNM 1020518 View Materials and 1020519 two complete series of transverse sections. These and several unsectioned specimens coll. by SAM from Croatia deposited at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C., USA.

Diagnosis

Prosorhochmus chafarinensis has no known morphological apomorphies. It differs from Prosorhochmus nelsoni and Prosorhochmus belizeanus sp. nov. in being viviparous and hermaphroditic ( Figure 1F View Figure 1 ) and from P. belizeanus sp. nov. in having acidophilic cephalic glands intermixed with the basophilic mucus cephalic glands in the pre-cerebral region (compare Figures 9C View Figure 9 and 6A View Figure 6 ). It differs from Prosorhochmus americanus in lacking well-developed purple cephalic glands (compare Figures 9C and 9A View Figure 9 ) and in having but a single juvenile per ovary. It differs from P. adriaticus in having a larger S/B ratio (0.52 on average compared to 0.25), but the data at hand are not sufficient to determine statistical significance. Central stylet (S) 80–130 Mm long (109.6 Mm average), significantly different from that of P. belizeanus sp. nov. but not P. nelsoni or Prosorhochmus claparedii (p50.05), basis (B) truncated, 136–260 Mm long (208 Mm average), significantly different from that of P. nelsoni and P. belizeanus but not P. claparedii ; S/B ratio 0.38 to 0.65 (0.52 average), significantly different from that of P. nelsoni and P. belizeanus but not P. claparedii ( Tables 2, 3). Prosorhochmus chafarinensis most closely resembles P. claparedii but differs from it by longer stylet and basis (see Tables 2, 3), although the data at hand are not sufficient to demonstrate statistical significance.

Habitat and distribution

On the encrusting alga Lithothamnion lichenoides on Isabel II Island (Chafarinas Island, 35 ° 119 N, 2 ° 259 W) ( Frutos et al. 1998). Additional specimens collected by SAM from the coast of Adriatic Sea near Croatian coastal towns Savudrija and Zambratija in the northwestern part of the Istrian Peninsula. In this location several individuals were found together on the moist sand under stones or on the lower surface of stones just above the low water mark at low tide ( Figure 1A View Figure 1 ). The worms seemed to prefer medium size stones resting on the fairly coarse, somewhat muddy sand. Specimens in Croatia were associated with another viviparous hoplonemertean – Arhochmus korotneffi (Bürger, 1985) comb. nov.

Remarks

Specimens collected by SAM from the Adriatic coast of Croatia were slightly longer than Prosorhochmus chafarinensis from Chafarinas Islands but otherwise conformed to the species description. Stylet characteristics, measured on six specimens from Croatia were not statistically significant from the originally described for P. chafarinensis by Frutos et al. (1998) (p50.05). We pooled the measurements and adjusted the ranges and means accordingly in the species diagnosis.

As reported by Frutos et al. (1998), Prosorhochmus chafarinensis is different from other species of the genus in having 3–8 muscle fibres (instead of a single fiber) in the lateral nerve cords. Our observations over the years show that hoplonemerteans typically have several muscle fibres associated with the lateral nerve cords. Often these fibres stick together giving the appearance of a single fiber, most likely due to fixation and subsequent dehydration of the tissues. We believe that this character has no taxonomic value. Similar to Prosorhochmus claparedii , P. chafarinensis is described as having a more complex frontal organ ending in a 90 ° bend compared to Prosorhochmus americanus ( Gibson and Moore 1985, p.149, plate I, fig. e; Frutos et al. 1998). As we mentioned before, this is a misinterpretation. All Prosorhochmus species examined by us have frontal organ of a similar structure and complexity (see Figures 4C–D View Figure 4 , 5A–C, 5G–H View Figure 5 , 8A–J View Figure 8 , 9D–F View Figure 9 ).

The differences between Prosorhochmus chafarinensis and Prosorhochmus claparedii are summarized by Frutos et al. (1998, p. 297, Table 2). These include lack of dorso-ventral musculature in the foregut region of P. claparedii , and presence of the neural supply in the posterior chamber of proboscis of P. claparedii . Our reinvestigation challenges both assertions. We did not find distinct nerves on crosssections of the posterior proboscis in P. claparedii . On the contrary, we found welldeveloped dorso-ventral muscles in the stomach and pylorus region in this species (see Figures 8K, L View Figure 8 ). Other suggested differences include absence of ciliation in the oesophageal epithelium of P. claparedii . We argue that this cannot be determined with confidence using standard light microscopy. Additionally, P. chafarinensis is supposed to differ from P. claparedii in lacking the postero-ventral stomach pouch. We observed that this character is intraspecifically variable in Prosorhochmus belizeanus sp. nov. and argue that it should not be used to distinguish between the species of Prosorhochmus .

To summarize, we found that Prosorhochmus chafarinensis is morphologically indistinguishable from Prosorhochmus claparedii , except for the difference in stylet (S) and basis (B) length and, possibly, S/B ratio. The respective stylet measurements of specimens from England used by Gibson and Moore (1985) in redescription of P. claparedii are nearly half the size of those of P. chafarinensis (see Tables II, III). The difference is somewhat obscured when our three specimens of P. claparedii from Roscoff, France are added to comparison. And since only the latter can be used for statistical comparisons, the measurements of the two species do not come out as significantly different. However, we believe that if more specimens of P. claparedii were available the difference would turn out to be significant. Furthermore, P. claparedii and P. chafarinensis can be distinguished molecularly. Sequence divergence between P. cf. chafarinensis (specimens from Croatia), and P. claparedii (material from the Atlantic coast of Spain and France) is 2.2% and 0.6% for 16S rDNA and COI, respectively ( Table 4).

| US |

University of Stellenbosch |

| SAM |

South African Museum |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Prosorhochmus belizeanus

| Maslakova, Svetlana A. & Norenburg, Jon L. 2008 |

Prosorhochmus chafarinensis

| Frutos 1998 |

Prosorhochmus chafarinensis

| Frutos 1998 |