Crocidura solita, Esselstyn & Achmadi & Handika & Swanson & Giarla & Rowe, 2021

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1206/0003-0090.454.1.1 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:7982B923-4CDC-44ED-A598-8651009DC7CC |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5793638 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/B8B27A48-E1C7-47F1-B0B8-938722284C32 |

|

taxon LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:act:B8B27A48-E1C7-47F1-B0B8-938722284C32 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Crocidura solita |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Crocidura solita , new species

LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:B8B27A48-E1C7-47F1-B0B8-938722284C32

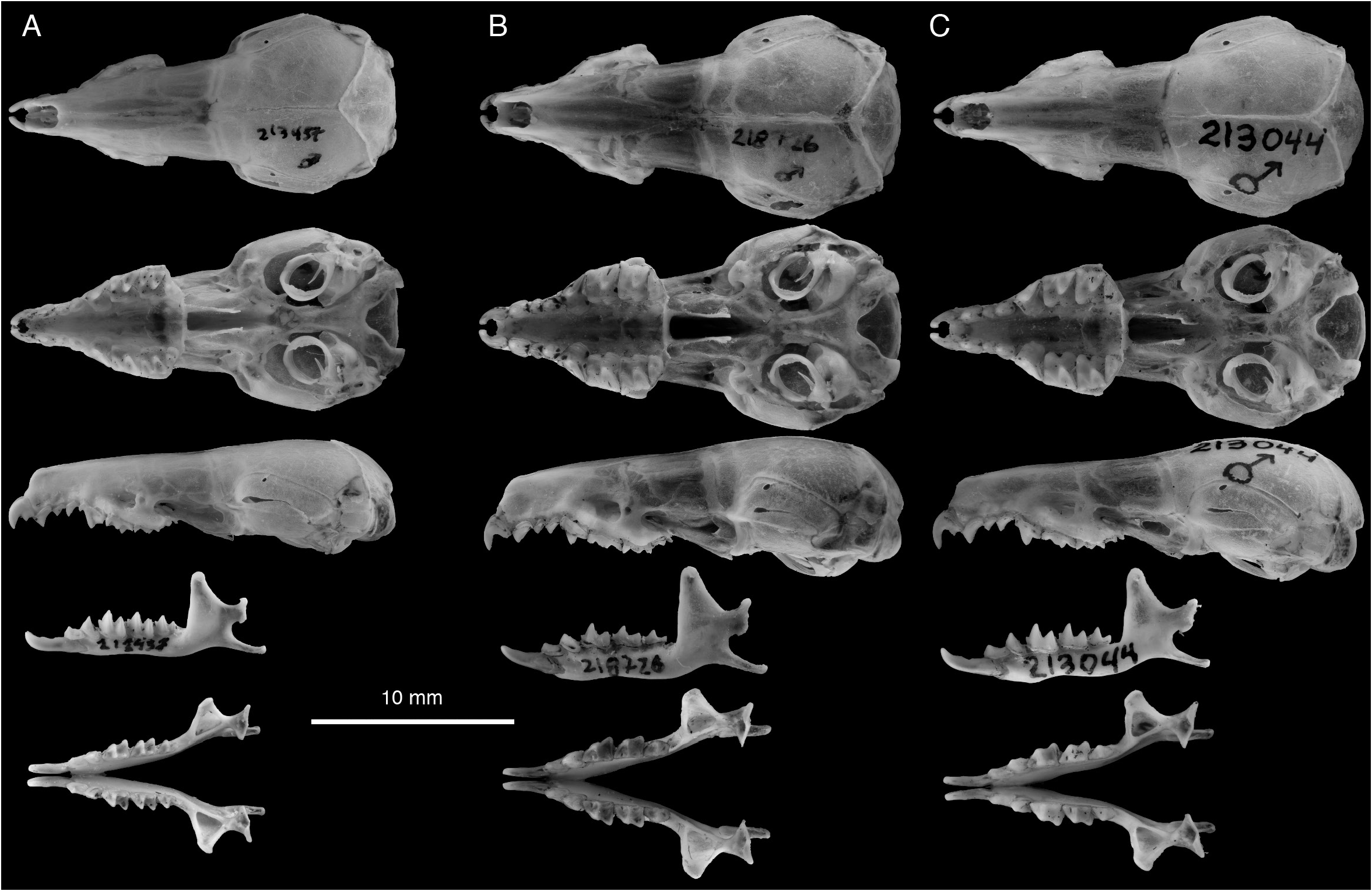

HOLOTYPE: MZB 43012 (= FMNH 213044 View Materials ), an adult male collected 1 March 2011 by J.A. Esselstyn. The specimen consists of a cleaned skull, fluid preserved body, and frozen tissue samples. External measurements from the holotype are 147 mm × 68 mm × 16 mm × 9 mm = 9.5 g. The voucher specimen with a tissue sample will be permanently curated at MZB, with an additional tissue sample retained at FMNH.

TYPE LOCALITY: Indonesia; Sulawesi Selatan; Enrekang ; Buntu Bato; Latimojong Village ; Karangan; Mt. Latimojong , Bantanase; 3.40755° S, 120.0078° E, 2050 m.

ETYMOLOGY: Solita is Latin for “usual,” used in recognition that this is another species of shrew with no striking phenotypic traits worthy of attaching a descriptive name.

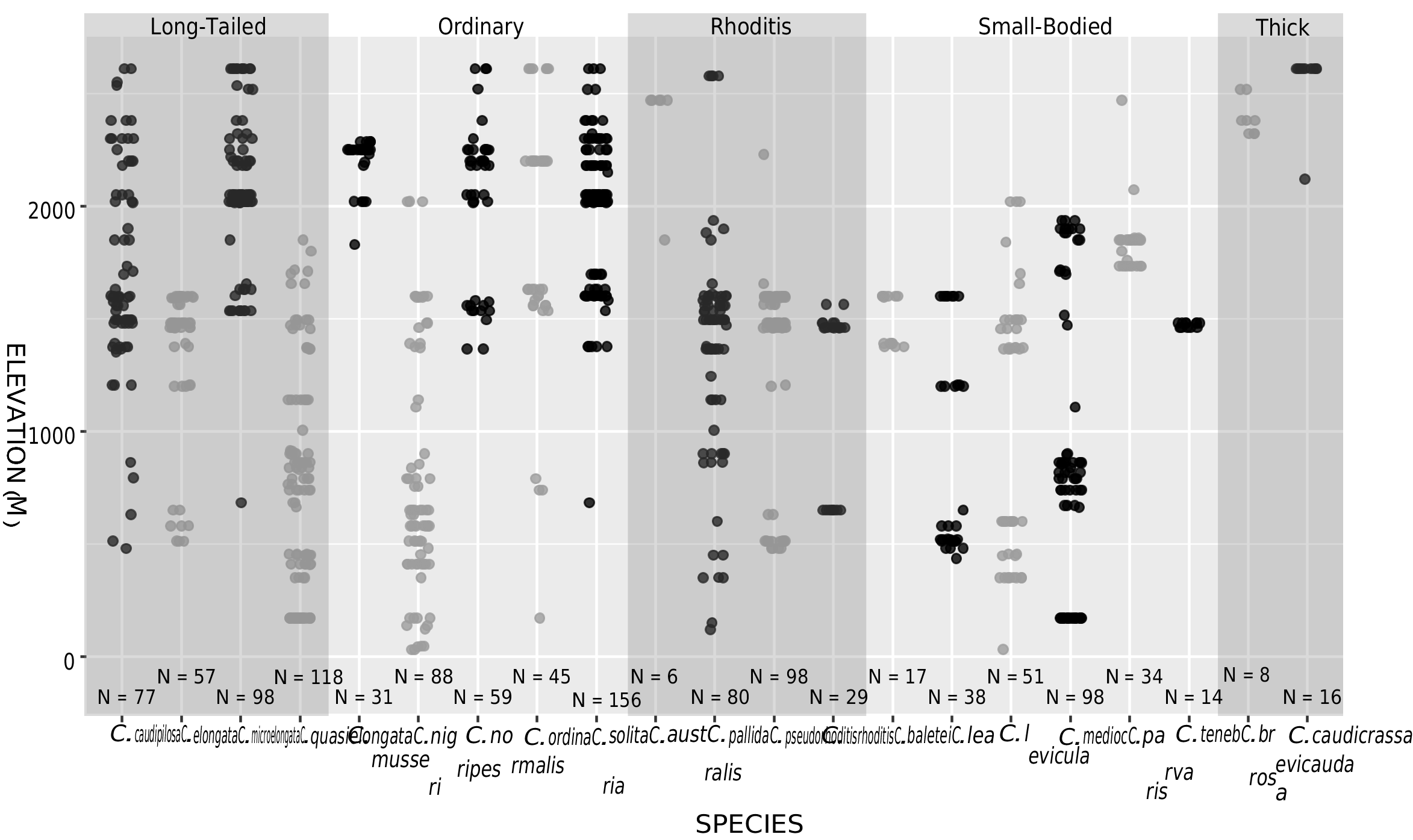

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION: We recorded Crocidura solita on three mountains in the west-central area of endemism (Mts. Latimojong and Rorekatimbo, Central Sulawesi Province; and Mt. Gandang Dewata, West Sulawesi Province; fig. 39 View FIG ). Records of this species span a broad range of elevations, from 700 to 2600 m. On Mt. Gandang Dewata, C. solita occurred syntopically with its sister species, C. ordinaria , at middle and high elevations (around 1600 and 2600 m; fig. 13 View FIG ; table 3 View TABLE 3 ).

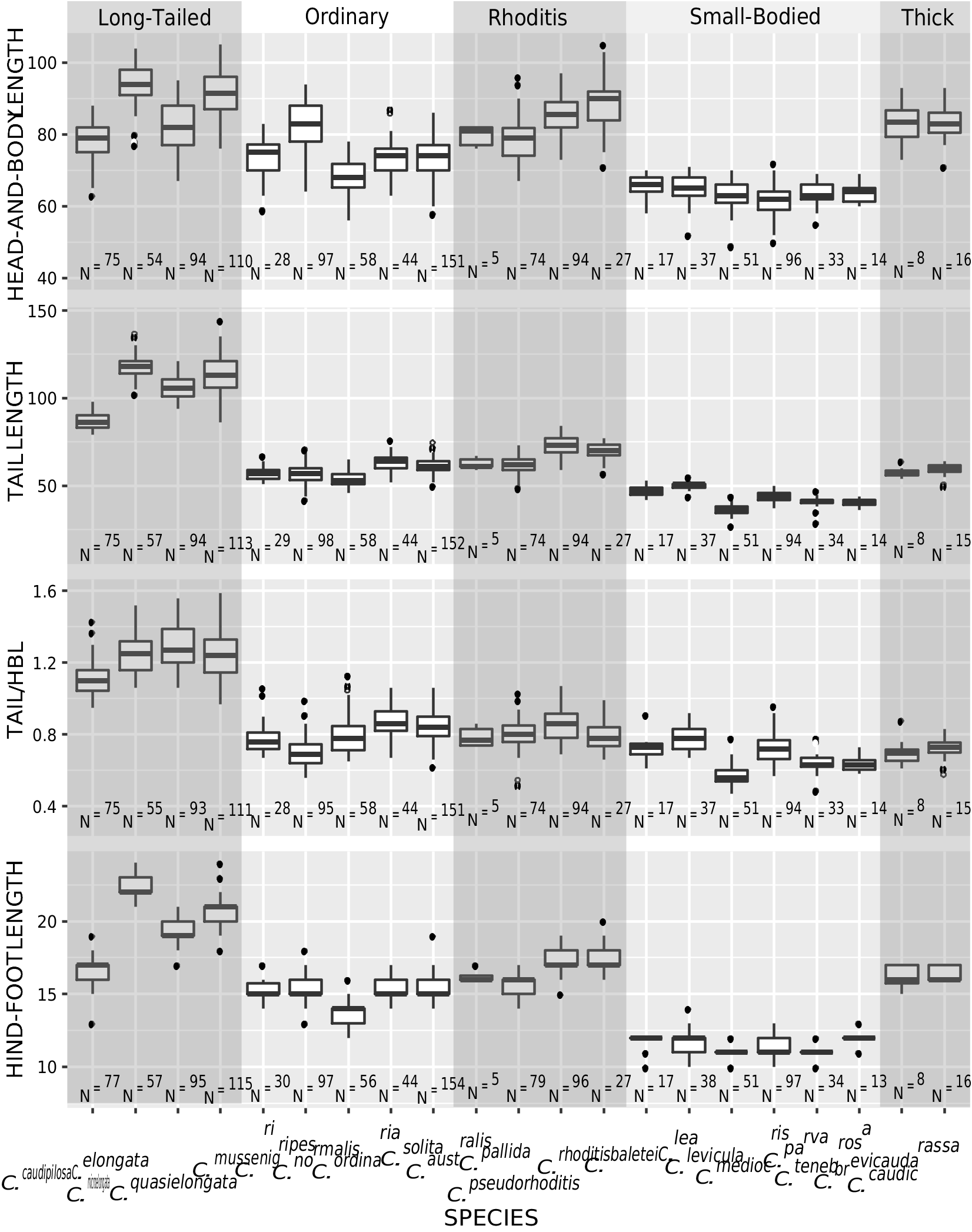

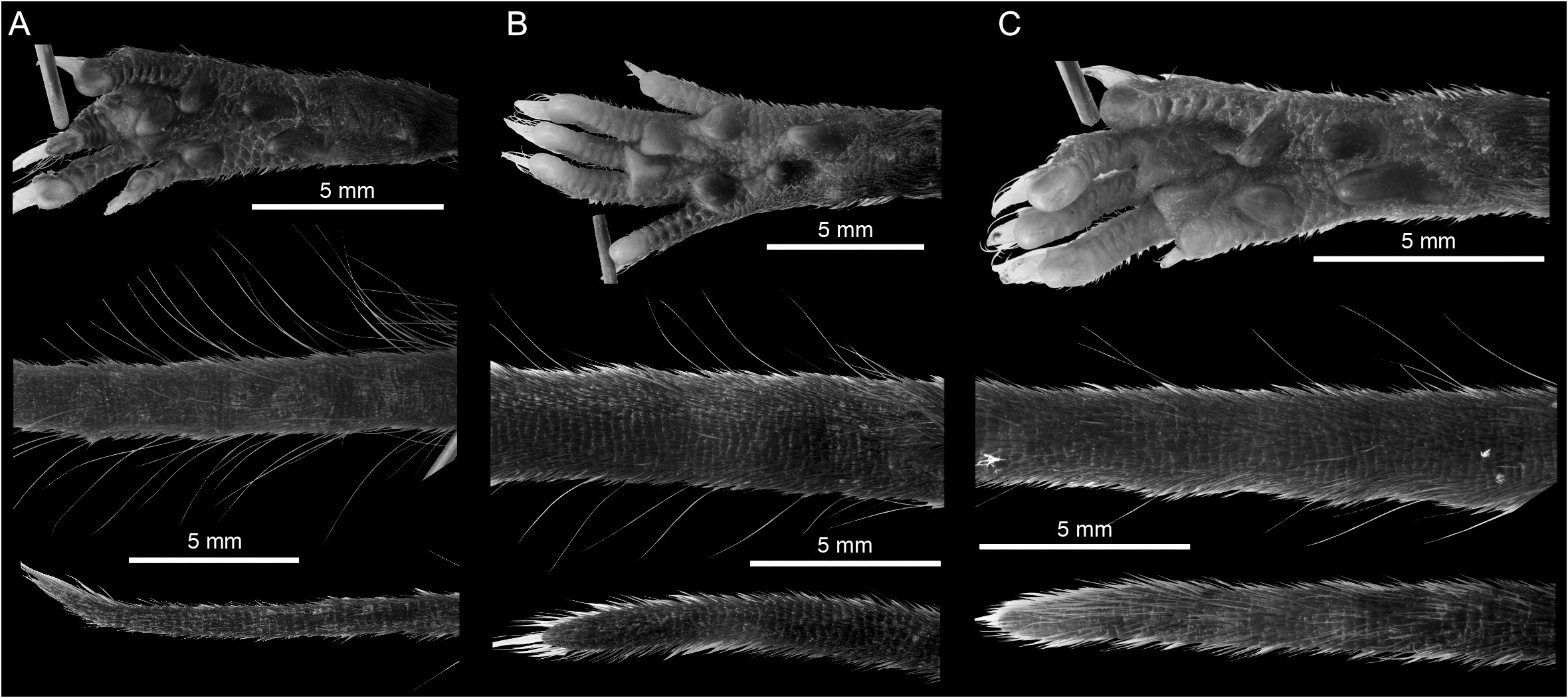

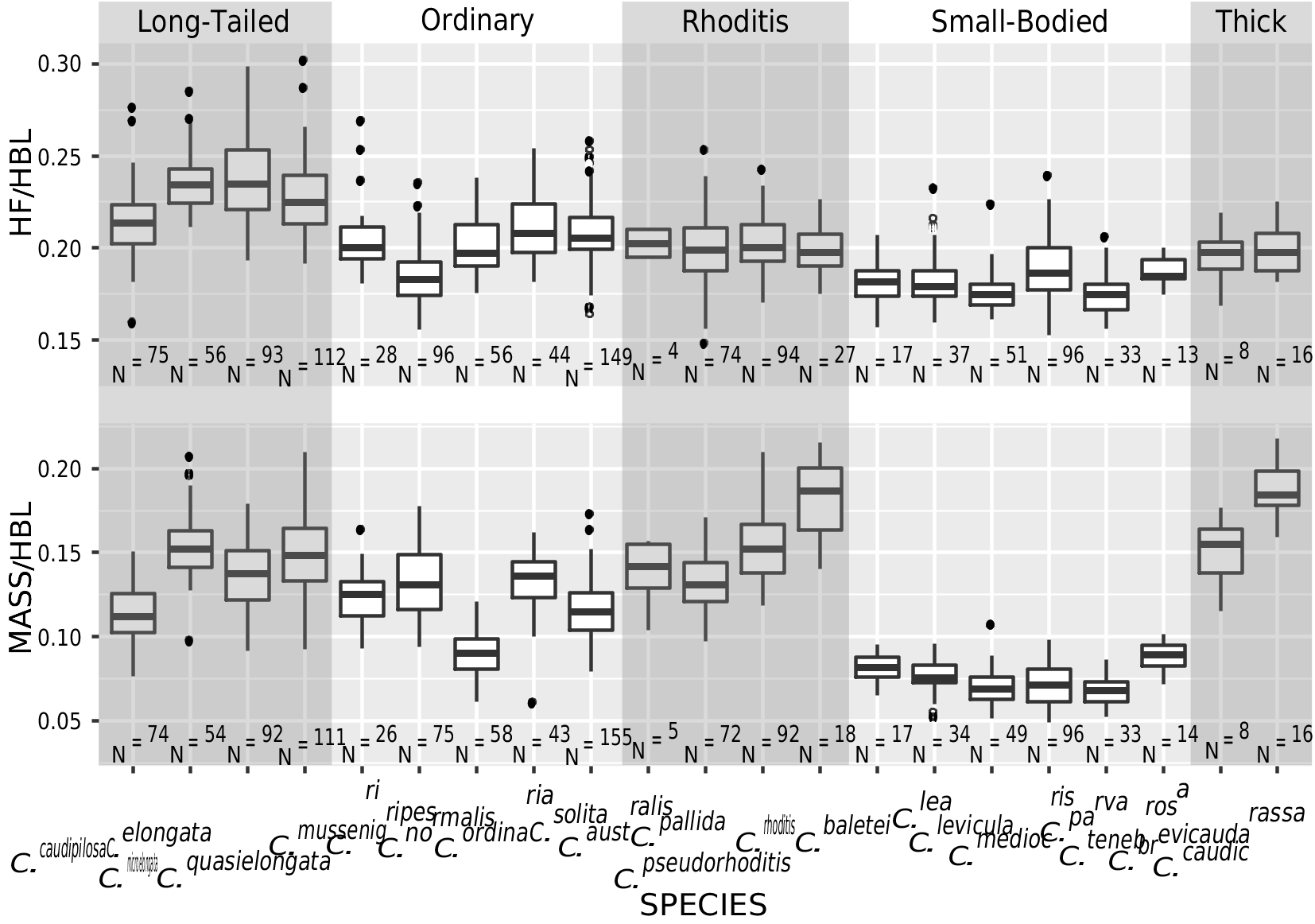

DIAGNOSIS: A medium-sized shrew ( tables 2 View TABLE 2 , 14 View TABLE 14 ) with a medium gray dorsal pelage and lighter gray ventral pelage. Tail length is slightly shorter than head-and-body length ( fig. 9 View FIG ). The tail is only slightly bicolored, but some individuals have at least a few white applied hairs, giving it a somewhat silvery appearance, particularly near the tip. Dorsally, the feet are paler than the surrounding pelage, typically transitioning from light brown posteriorly to nearly white on the digits ( fig. 40C View FIG ). Ventrally, the feet are darker around the thenar and hypothenar pads than on the surrounding plantar and palmar surfaces; the hind feet tend to be darker than the forefeet. The external ears are slightly paler than the surrounding pelage. The mystacial vibrissae are short and mostly unpigmented, but a few of the longer, more posterior vibrissae are pigmented at their base. The skull is average in length (relative to HBL) for a Sulawesi shrew and slightly wide at the braincase and interorbital region relative to skull length ( fig. 10 View FIG ). The braincase is rounded, but with a somewhat prominent lambdoidal crest ( fig. 41C View FIG ). The suture between the squamosal and parietal bones is often open, leaving a long slit below the sinus canal. The interorbital region is well tapered. The maxillary bridge is thin.

COMPARISONS: For comparisons to most species, see the Crocidura ordinaria comparisons section above. Compared to C. ordinaria , the pelage is less dense (i.e., shorter hairs on the dorsum) and both the pelage and feet are paler on average and the body is less stocky ( fig. 17 View FIG ). The skull of C. solita is slightly smaller, and it is also narrower both absolutely and relative to skull length ( figs. 10 View FIG , 42 View FIG ), with a narrower palate and less robust dentition ( table 14 View TABLE 14 ). The suture between the squamosal and parietal bones is often open, leaving a long slit in C. solita , but this suture is usually closed in C. ordinaria .

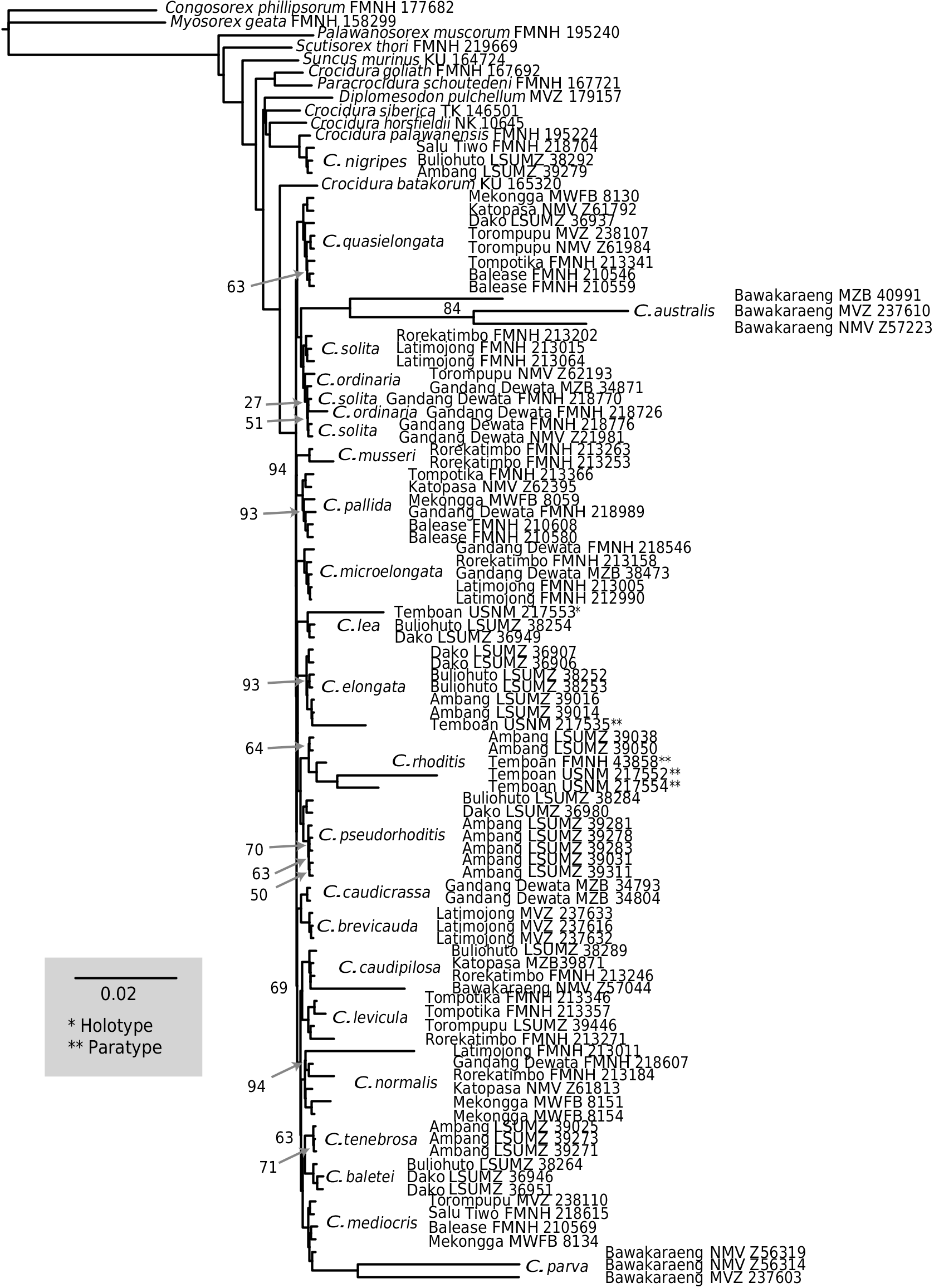

COMMENTS: We posit that Crocidura solita and C. ordinaria are phenotypically similar sister species. Morphologically, we note subtle differences of body size, relative skull widths, and coloration. In the absence of other evidence, these slight morphological differences would be too little to justify dividing these specimens into two species, and we would not have suspected multiple taxa were represented by these specimens if it were not for our use of mitochondrial sequences. Syntopic specimens of these two species from Mt. Gandang Dewata are separated by a mitochondrial Jukes-Cantor distance of 0.064 (0.087 when all specimens are used in the calculation) and specimens of each species from the zone of parapatry is more closely related in the mitochondrial gene tree to conspecifics from other parts of the island ( figs. 4 View FIG , 5 View FIG ; supplementary data S2–S5). The mitochondrial distance between syntopic individuals and closer relatedness to allopatric populations suggests that these phenotypically similar animals are most likely evolving independently of each other.

In our mitochondrial gene trees, Crocidura ordinaria and C. solita are well-supported sister taxa and reciprocally monophyletic ( figs. 4 View FIG , 5 View FIG ). Our inferences using UCEs again indicate a close relationship with the two species forming a clade, but each species is reciprocally paraphyletic in our concatenated and species-tree inferences, the latter of which treated individuals as “species” and therefore did not force monophyly ( figs. 7 View FIG , 8 View FIG ). Our phylogenetic estimate from concatenated

nuclear exons also inferred reciprocal paraphyly for this species pair (supplementary data S6).

We tested species delimitation models with BPP between Crocidura solita and C. ordinaria using a dataset that included 64 C. solita and 22 C. ordinaria sampled from across their ranges. The alignment of five exons is 82% complete. All analyses of this dataset supported species delimitation with 1.0 posterior probability.

Overall, we interpret the combination of subtle morphological differences (weak evidence), deep mitochondrial divergence in the face of syntopy (strong evidence), and our BPP results (modest evidence) as supporting species distinction. We conclude that the paraphyly in our UCE inferences is most likely the result of incomplete lineage sorting and ancestral polymorphism. In coming to this conclusion, we are admittedly leaning heavily on mitochondrial data. However, the great differences between the mitochondrial sequences where the two species cooccur provides strong evidence for differentiation, at least between females. If these specimens represented a single species, we presume that any substantive gene flow would lead to one of the divergent mitochondrial types being favored, either because it is independently superior to the other, or because it is superior in its integrative functioning with the relevant parts of the nuclear genome (sensu Sloan et al., 2017; Hill, 2019). Mitochondria are foundational to energy metab- olism; viewing them as a neutrally evolving locus would ignore their functional importance and extensive interactions with nuclear gene products ( Nabholz et al., 2008; Lane, 2011; Sloan et al., 2017; Tobler et al., 2019). Although many cases of mitochondrial divergence within species have been documented, they rarely involve sympatry of the divergent mitochondrial types (but see Wayne et al., 1990; Morgan-Richards et al., 2017), and far more often than not, mitochondrial divergence is consistent with species limits ( Hebert et al., 2003; Monaghan et al., 2005; Esselstyn et al., 2012a; Cao et al., 2016). Taking in all the evidence, we believe these two sets of samples represent independently evolving populations that should be recognized as species despite the limited evidence for phenotypic or nDNA differentiation.

SPECIMENS EXAMINED: Mt. Gandang Dewata ( FMNH 218770 , 218773–218780 , 218976 ; MZB 34807 , 34811 , 34813 , 34814 , 34823 , 34826 , 34828 , 34829 , 34831 , 34881 , 34885 , 34887 ), Mt. Latimojong ( MZB 41669–41677 ; FMNH 213009 , 213012 , 213015–213019 , 213029 , 213031 , 213033–213037 , 213039–213043 , 213045– 213071 ; MVZ 237585–237593 , 237596 , 237598 , 237599 , 237611 , 237617 , 237619–237621 , 237628 , 237634 , 238122 ; MZB 43012 ; NMV C38479 , C38493 , C38516 ), Mt. Rorekatimbo ( FMNH 213163 , 213194–213245 , 213270 ), Rindingallo, Tana Toraja ( MSB 93125).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.