Promephitis lartetii Gaudry, 1861

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5252/g2016n4a5 |

|

publication LSID |

urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:528EED12-2BF4-4BA6-A3DC-7706ED8C5072 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03D587C0-1E02-6F6B-CEA7-FB57FEA0F96A |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Promephitis lartetii Gaudry, 1861 |

| status |

|

Promephitis lartetii Gaudry, 1861

Promephitis hootoni Şenyürek, 1954: 281 , figs 1-14.

HOLOTYPE. — Much distorted skull and attached mandible from Pikermi, Greece ( MNHN.F.PIK3019).

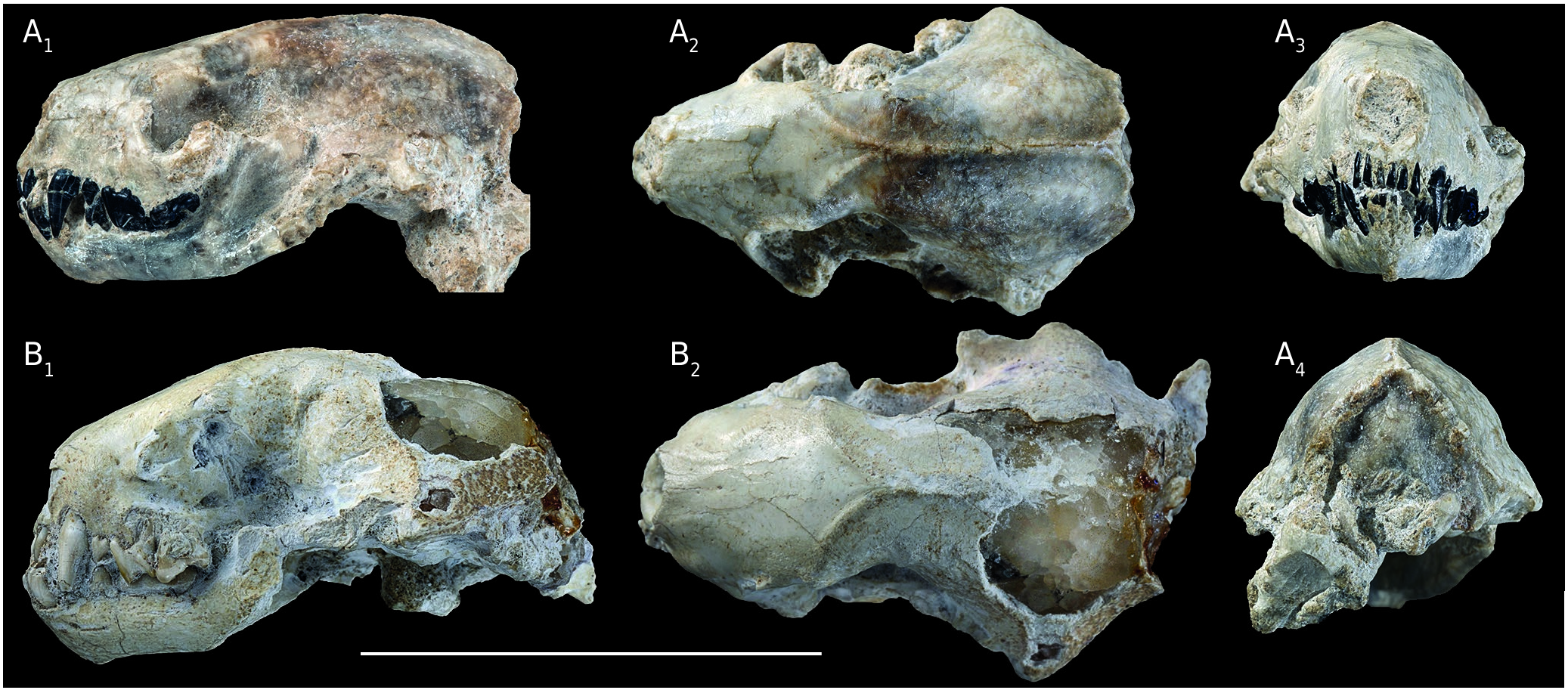

REFERRED MATERIAL FROM BULGARIA. — There are three skulls of Promephitis lartetii from Hadjidimovo, and one from Kalimantsi. The latter, K- 9504, is very incomplete as it includes only the dorsal part of the braincase and frontal area; HD- 9506 is a relatively complete cranium but is somewhat crushed dorsoventrally and the dentition is in poor condition; HD- 9507 is much distorted and lacks most of the snout and dentition, except the right P4-M1; HD- 9508 is an undistorted skull with attached mandible, but it lacks most of the parietals and occipital.

DIAGNOSIS. — A species of Promephitis slightly larger than P. majori ; snout more inflated, broader over the canines; occipital lower.

DESCRIPTION

HD-9508 ( Fig. 1B View FIG ) is very similar to HD-9505, assigned above to P. majori , and we will mostly note the differences. It is slightly larger; the difference does not exceed what one would expect within a single species, but the other specimens are dimensionally close to HD-9508 rather than intermediate between it and HD-9505, suggesting bi-modal size distribution ( Tables 1; 2). The face of HD-9508 is distinctly broader in the frontal region and the snout is more inflated; the post-orbital processes are slightly better developed, but remain weak. The occipital is relatively lower. A minute P2 is present on the right side at least. The buccal cingulum of M1 is less prominent than in HD-9505. A minute p2, displaced lingually, is visible between the canine and p3. The p3 and p4 are similarly tall and slender, with mesial and distal accessory cuspids.

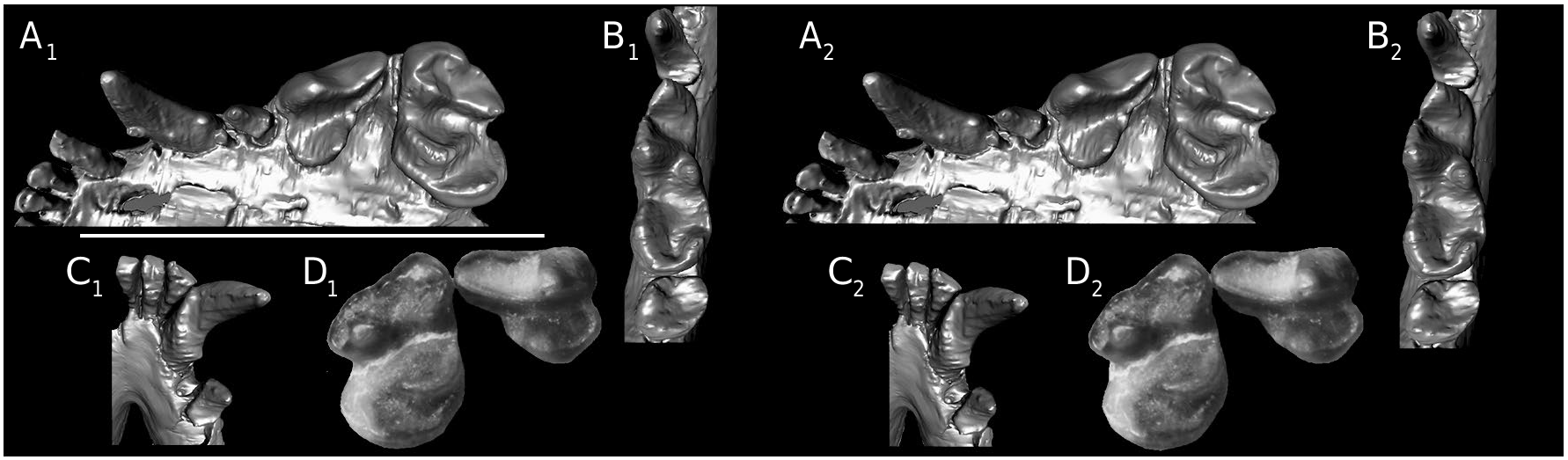

Skull HD-9506 is similar in size to HD-9508 and has the same broad snout, but no details are observable.HD-9507 has well-preserved P4 and M1 ( Fig. 3D View FIG ); on P4 there is a distinct ridge descending from the hypocone around the mesio-lingual part of the tooth, which is more expanded than in HD-9505, although without forming a distinct protocone. The buccal cingulum of M1 is moderate. The skull fragment K-9504 also agrees in size and snout width with HD-9508; its sagittal crest was certainly shorter, if not absent, but whether this is due to individual variation or to the age difference between the sites is unknown.

COMPARISONS

We compared the Bulgarian material with most modern species of Mephitidae and to fossil material from Pikermi (MNHN) and Perivolaki (LPGUT) in Greece. In addition, G. Koufos made available photos and cast of skulls from Samos, whose original specimens are stored in the AMNH and NHMW, and M. Sotnikova provided photos of material from Novo Elisavetovka, Ukraine.

All skulls of Promephitis from Hadjidimovo and Kalimantsi are very similar, and the presence of two species is not obvious at first sight. However, of the two best preserved skulls, HD-9508 is distinctly larger than HD-9505, and some of the few dental measurements are also larger. The main difference is in the greater inflation of the fronto-maxillary area, especially in the rostral part; the width of the maxilla over canine roots, in front of the infra-orbital foramina, is 18.9 mm in HD-9508, in contrast to only 13.6 mm in HD-9505. Given the documented co-occurrence of two different species of Promephitis in the late Miocene of China ( Wang & Qiu 2004), and of modern species of both Mustela and Martes in Europe ( Geptner et al. 1967; Wolsan 1999a; Šálek et al. 2013), we have no hesitation in referring these two skulls to different species, but it is not so easy to clarify the systematics of European and Eastern Mediterranean forms of the genus.

Few characters are observable on the type specimen of the type species, P. lartetii from Pikermi, because of its extreme crushing, and poor preservation of the teeth. The few cranial measurements provided by Gaudry of the specimen that he figured ( Gaudry 1862: pl. 6), repeated by several authors since then, are either grossly incorrect or unreliable. Neither the few dental measurements that can be taken nor the morphology differ from those of the two Hadjidimovo species. Pilgrim (1931: 53) diagnosed P. lartetii in having a “metaconid of m1 somewhat in front of the protoconid”, but this is clearly incorrect. However, the mandible of the holotype is distinctly longer from condyle to most rostral point of the dentary ( 44.5 mm, slightly overestimated by crushing) than that of HD-9505 ( 36 mm), and closer to that of HD-9508 ( 42.5 mm), so that there is no reason to distinguish HD- 9508 from P. lartetii , implying that HD-9505 must belong to another, smaller species.

The holotype and only specimen of Promephitis gaudryi Schlosser, 1902 , an m1 from the Vallesian (?) of Melchingen, Germany, obviously does not belong to this genus, as noted by Pilgrim (1933) and later authors, because of its small talonid, low trigonid cuspids, and lack of accessory roots. There is no reason to include it in the Mephitidae ; Pilgrim (1933) assigned it to Trocharion Major, 1903 .

The next species to be described was P. maeotica Alexejew, 1915 from the Turolian of Novo Elisavetovka in Ukraine. The skull is clearly distinct from those of the Bulgarian and Pikermi forms in its larger size, gently converging temporal lines, and especially in its narrow P4 with a shallow buccal depression, short hypocone located centrally instead of more distally, small but distinct protocone that bulges mesially, and extremely twisted M1. P. maeotica is clearly distinct from the Balkan forms. Zdansky (1937) described some remains from Baode, China, as P. cf. maeotica , with which they agree in size, but Wang & Qiu (2004) referred them to another species, P. hootoni Şenyürek, 1954 (see below).

Promephitis alexejewi Schlosser, 1924 was erected for scrappy remains from Ertemte, China. Wang & Qiu (2004), on the basis of Schlosser’s measurements, assumed that this species had a long P4 compared to M1 but the difference is less than stated by Schlosser ( Table 2), and the two teeth might well be from two different individuals. Besides large size, probably due to the young geological age of the localities (the species was also reported from the uppermost Miocene of Venta del Moro in Spain by Montoya et al. 2011), P. alexejewi lacks distinctive features.

Promephitis malustenensis Simionescu, 1930 (this name was chosen by Wang & Qiu [2004], in preference to P. rumanus , erected by Simionescu for the same type specimen), is based upon a mandible from Măluşteni, Romania, which has far too long a premolar row to belong to this genus, but the poor illustration ( Simionescu 1930: fig. 13) forbids identification.

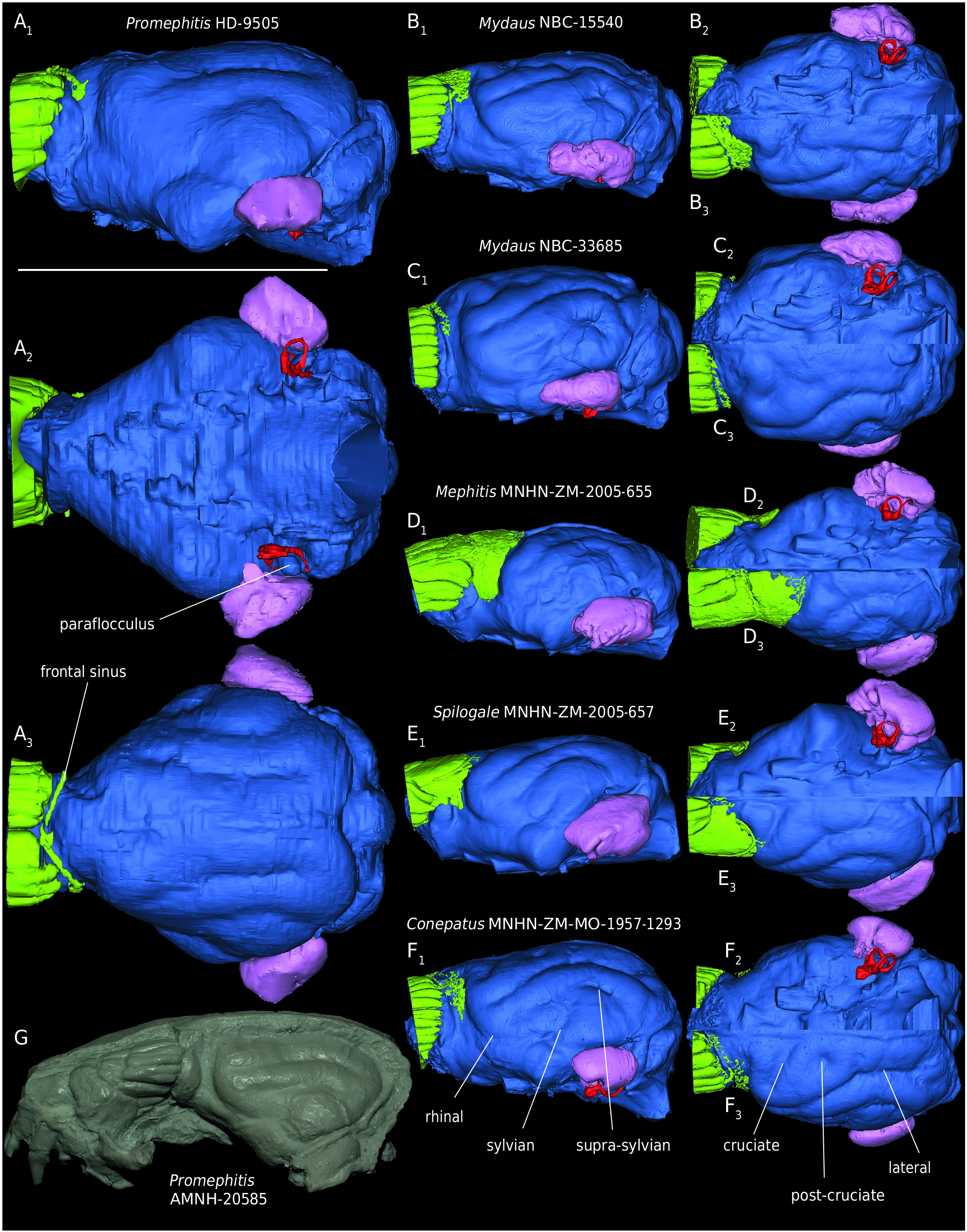

Pilgrim (1933) erected a new species from Samos, P. majori . Cranial, dental and mandibular features do not differ from the few ones that can be observed in P. lartetii . The brain, observable on a cast of the holotype AMNH 20585 ( Fig. 2G View FIG ), is very similar to that of HD-9505. Dental features are also virtually identical to those of P. lartetii . In contrast to Pilgrim’s claims, there is no evidence that: 1) M1 is shorter than P 4 in P. lartetii ; 2) a parastyle was present in the P4 of P. majori , as the missing mesial part of P4 may just be the paracone; and 3) a P1 and/or a P2 was present in P. lartetii . The clearest difference is of size: the teeth are slightly smaller in P. majori ( Table 2), and so is the length of the mandible ( 35 mm according to Pilgrim [1933], vs 44.5 mm in the type of P. lartetii ). In addition, P. majori differs from specimens assigned to P. lartetii (other than the distorted type) in its relatively high occipital, a feature also present in HD-9505. Thus, P. majori differs from P. lartetii in the same way as HD-9505 differs from HD-9508, and we refer HD-9505 to P. majori and HD-9508 to P. lartetii .

Şenyürek (1954) erected P. hootoni for a partial skull and associated mandible from the Turolian of Küçükyozgat (Western Turkey); listed differences from previously named species are either subtle or non-existent, being based on Gaudry’s (1862) incorrect drawings and measurements (presence vs absence of postorbital process and of p2, shape of the ventral mandibular corpus). In size and inflation of the snout, the type of P. hootoni matches P. lartetii and HD-9508, so that there is no reason to separate it from this species, as also suggested by Koufos (2006). Bonis (2005) described as P. hootoni a mandible from Akkaşdağı ( Turkey); assuming that the scale ( Bonis 2005: fig. 14) is correct, this mandible is indeed likely to represent P. lartetii .

Promephitis pristinidens Petter, 1963 , from the Vallesian of Spain, is based on a maxilla fragment in which P4 has a distinct parastyle and a weak lingual talon with no distinct cusp, while M1 has a poorly inflated hypocone and weak buccal cingulum. These are primitive features, but no derived character links this form with later Promephitis , and we consider the generic assignment unsupported, although it could be an early member of this group.

Promephitis brevirostris Meladze, 1967 from Bazalethi in Georgia is so poorly known that it is better to restrict the name to the type series, and regard it as a nomen dubium. The loss of one pair of incisors may have occurred postmortem.

Among other significant remains of Promephitis in the Eastern Mediterranean, there is a skull from Samos NHMW A4798, discussed by Koufos (2006), who concluded that it suggests the presence of a larger species at Samos, in addition to the smaller P. majori . We agree with him; although the occipital is dorsoventrally compressed, in its broad, inflated snout and overall size, A4798 matches HD-9507 and HD-9508 and we assign it to P. lartetii .

The material from Perivolaki in Greece is crushed and distorted, but the mandible length of LPGUT-PER-1278 ( 42.2 mm) is close to those of HD-9508 and of the type of P. lartetii , a species to which Koufos (2006) ascribed it. We agree with his identification, even though P3, p3, and p4 are larger than usual in this species.

We conclude that, in the Turolian of Western Eurasia, Promephitis includes three species, in decreasing size order P. maeotica from Novo Elisavetovka, P. lartetii from Pikermi, Samos, Perivolaki, Küçükyozgat, Akkaşdağı, Hadjidimovo and Kalimantsi, and P. majori from Samos and Hadjidimovo. Thus, in these two latter sites (although the precise origin of the Samos fossils is unknown), both species co-exist, the smaller form being rarer.

From the Pliocene of China, He & Huang (1991) described P. maxima ; it is much larger than Upper Miocene forms but there is reason to doubt the generic attribution, although the illustrations are too imperfect for detailed comparisons.

Wang & Qiu (2004) described rich collections from the Upper Miocene of China, and named two species P. parvus and P. qinensis , in addition to what they called P. hootoni which is, in our opinion, identical with P. lartetii (the teeth are very similar to those of HD-9507, and differ from other Chinese species, in their much expanded P4 talon, strong buccal cingulum around the paracone of M1, and deep distal notch on this tooth; their size is similar to those of P. lartetii , and the muzzle is broad is both forms). We have not seen this material, but the coexistence of two species of different sizes, as in some Eastern European sites, is worth noting.

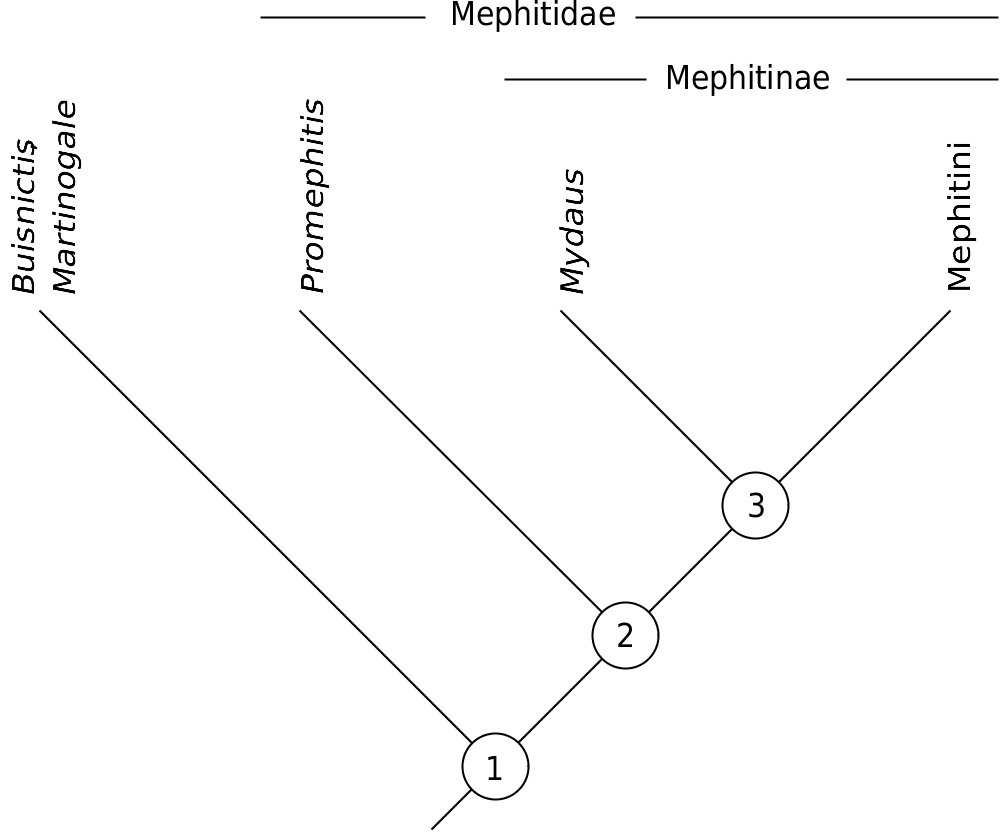

CONTENTS OF THE FAMILY MEPHITIDAE

The removal of the Mephitidae from the Mustelidae is now generally accepted. The inclusion of the South-Asian Mydaus (including Suillotaxus Lawrence, 1939 ) in the Mephitidae , first suggested by Pocock (1921) and more recently by Petter (1971) and Radinsky (1973), has been confirmed by recent molecular analyses (e.g., Flynn et al. 2005; Nyakatura & Bininda-Emonds 2012; Sato et al. 2012). All recent analyses ( Bryant et al. 1993; Finarelli 2008; Wang & Carranza-Castañeda 2008; Eizirik et al. 2010) recognize that the three extant genera of New World mephitids, together with the closely related Pleistocene genera Osmotherium Cope, 1896 and Brachyprotoma Brown, 1908 but to the exclusion of Eurasian Mydaus , Promephitis and Palaeomephitis , form a monophyletic group, the Mephitini . Relationships of other purported Mephitidae with this core group are discussed below.

Miocene Eurasian Forms

Palaeomephitis steinheimensis Jäger, 1839 is based upon the posterior half of a Middle Miocene juvenile skull from Steinheim described by Helbing (1936) as Trocharion albanense , and further discussed by Wolsan (1999b). Helbing (1936) noted that it differs from Conepatus View in CoL and Promephitis majori in that the condylar foramen is distinct from the posterior lacerate foramen, but this is incorrect, as they are also separated in Conepatus View in CoL and in HD-9505, while Pilgrim (1933) made no positive observation on the type of P. majori . Wang et al. (2005) accepted P. steinheimensis as a member of the Mephitidae View in CoL . However, this family attribution solely rests on the assumption that the enlarged mastoid sinus is homologous with the mephitid one, i.e., that it is an expanded epitympanic recess, but the large opening to which Wolsan (1999b) gave this name faces ventrally instead of medially as in the Mephitidae View in CoL , showing that this area is imperfectly preserved. Given that this partial cranium is probably ( Wolsan 1999b) of the same taxon as the highly derived teeth called Trochotherium cyamoides Fraas, 1870 , and that it further differs from the Mephitidae View in CoL in the presence of a supra-meatal fossa and large caudal entotympanic, we believe that the mephitid affinities of Palaeomephitis remain doubtful. What is known of the still earlier Miomephitis Dehm, 1950 also lacks clear mephitid characters and is best left aside. Proputorius Filhol, 1890 , is known only by dental and mandibular remains that display no exclusive mephitid features. In the best known species, P. sansaniensis Filhol, 1890 , from the Middle Miocene of Sansan, the P4 has a very small and mesially located protocone ( Peigné 2012: figs 88, 89), unlike that of modern Mephitidae View in CoL ; the seven isolated m1s have no accessory roots. Pending cranial evidence, we do not include this genus in the Mephitidae View in CoL . The m1 of the Vallesian type species of the poorly known Mesomephitis Petter, 1967 , M. medius ( Petter, 1963) from Can Llobateres, Spain, differs from that of the Mephitidae View in CoL in its low lingual talonid margin and lack of accessory roots, and inclusion in this family is poorly supported. We conclude that Promephitis is the only definite fossil Old World member of the Mephitidae View in CoL .

American forms

Wang & Carranza-Castañeda (2008) included in one clade, together with what we have called Mephitini above but to the exclusion of Mydaus and Promephitis , the Miocene to Pliocene Martinogale Hall, 1930 and Buisnictis Hibbard, 1950 . They defined this clade by: 1) the presence of a parastyle on P4; 2) a hypoconid taller than the entoconid on m1; and 3) a cingulum not surrounding the protocone on M1. However, characters (1) and (2) are also present in Bulgarian Promephitis , and character (3) is quite variable, as we have observed many Mephitini in which the cingulum surrounds the protocone of M1.

In fact, a previously unnoticed character clearly separates modern and Plio-Pleistocene forms from earlier North American ones: in the latter, the P4 lingual cusp is clearly a protocone, because it is located mesially or very mesially ( Hibbard 1950: fig. 21, in Buisnictis meadensis ; Stevens & Stevens 2003: fig. 9.8, in Buisnictis chisoensis Stevens & Stevens, 2003 ; Wang et al. 2005: fig. 5, in Martinogale faulli Wang, Whistler & Takeuchi, 2005 ; Wang et al. 2014: fig. 5A, in Buisnictis metabatos Wang, Carranza-Castañeda & Aranda-Gómez, 2014 ); the P4 of M. alveodens remains unknown, since the tooth described under this name by Baskin (1998: 159) belongs to M. faulli (J. A. Baskin pers. comm.). This sharply contrasts with the condition in modern and Pleistocene American Mephitini , also found in Mydaus and Promephitis , in which the lingual cusp interlocks with the trigonid of m1 and is therefore a hypocone. We regard this difference in homology of the lingual cusp of P4 as fundamental, and sufficient to exclude Martinogale and Buisnictis from the clade containing Promephitis and modern Mephitidae . It echoes to the suggestion of Baskin (1998), followed by Stevens & Stevens (2003), that the American “mephitids” were the result of two migration waves, one in the Clarendonian giving rise to Martinogale and Buisnictis , and a second one in the early Blancan giving rise to modern and closely related genera. If the inflated mastoid sinus of Martinogale and Buisnictis is homologous of the one found in modern Mephitidae , these genera could be the sister group of this family, but they are not part of the clade in which the P4 lingual cusp is a hypocone. As a consequence, we will restrict the following discussion to these latter forms.

PHYLOGENY OF THE MEPHITIDAE

Parsimony analysis

The main distinctive characters of Promephitis , of modern genera, and of the purported American Clarendonian mephitids are listed in Appendix 1. A parsimony analysis conducted with TNT ( Goloboff et al. 2008), using any of the latter as outgroup, yields a single shortest tree shown in Appendix 2, of which Figure 4 View FIG would be a simplified version. Promephitis appears as the sister group of a clade, including all modern forms, defined by several characters reflecting increased brain complexity and a stronger superficial masseter muscle. This might look surprising given the overall skull similarity between Promephitis and modern American forms, but the cladogram suggests that reluctance to admit Mydaus within the Mephitinae is based upon features that are in fact autapomorphic. It could be argued that the derived brain characters that unite Mydaus with the American Mephitini are merely the consequence of the well-known increased complexity of carnivore brains over time, and could have in fact occurred in parallel, as also suggested by the very unlikely reversal that is inferred for Mephitis . Still, this cladogram is in agreement with chronology, and it is also informative in highlighting the numerous autapomorphies of Promephitis and Mydaus , but we certainly do not take it at face value.

Pleistocene and modern American forms ( Mephitini ) share small incisive foramina, a larger P4 parastyle, complete loss of P4 protocone, and a shelf-like hypocone more mesially located than in Eurasian forms, a mandible with expanded angular area, and loss of the entepicondylar foramen in the humerus. Their monophyly matches geography, and thus is strongly supported. Some further characters used by Finarelli (2008) to define the American clade; but, in contrast to his figure 3, their mastoid process is not weaker than in Promephitis , the metacone-metaconule crest is not better indicated on M1, and the m1 is not more basined, so that the only remaining additional synapomorphy of the Mephitini would be the reduction of the buccal cingulum of M1. However, this cingulum is so strong in Promephitis that it is more probably its condition that is derived.

A Eurasian Clade?

Wang & Carranza-Castañeda (2008) recognized the fossil and recent American and Eurasian Mephitidae as sister-groups. Of the characters that they used to define the Eurasian clade, the reduction of P2 and the lengthening of M1 are also found in most American forms, and the exclusion of the maxillae from the border of the incisive foramina is hard to document because these bones are fused with the premaxillae (even the CT-scans failed to visualize their limits). Wang et al. (2005) also considered as a derived feature of Eurasian forms the lack of a notch between entoconid and metaconid in m1, but this notch is present in Mydaus and Promephitis . The only important feature shared by Mydaus and Promephitis is the shape of the hypocone of P4.

The Position of Promephitis

Compared to other Mephitidae , Promephitis has both more primitive and more derived characters. Among the latter are some features of the dentition, such as the marked basal cingulum on canines, the reduction of the anterior premolar series, and the very large M1 with a prominent buccal cingulum; Promephitis brought these trends further than other mephitids. However, it also retains primitive traits that are lost in Mydaus and American Mephitini . The brain remains at a very primitive stage of folding. The zygomatic arch is of normal size, which is probably related to a deep masseteric fossa in the mandible, which lacks the ventral flat extension of the Mephitinae ; in the latter, the very slender zygomatic arch, shallow fossa and ventrally expanded angular region are probably related to the greater importance of the superficial masseter, which might, as in Procyon ( Gorniak 1986) , originate on an aponeurosis and not on the arch itself. Lastly, the subarcuate fossa is deep; the polarity of this character is debatable, but the resemblance of Promephitis with Mustela is striking.

THE POSITION OF MYDAUS

Finarelli (2008) excluded Mydaus from a clade consisting of Promephitis and the Mephitini , defined by: 1) more anterior choanae; 2) lack of a condyloid canal; 3) M1 hypocone formed by swelling of the cingular ridge; 4) parastyle stronger than metastyle on M1; and 5) M1 parastyle oriented mesiobuccally. In fact, the very caudal choanae of Mydaus are obviously derived, a condyloid canal is present in Promephitis , and there is no reason to differentiate the origin of the M1 hypocones in all these taxa, so that the only remaining difference is the absence of styles in the M1 of Mydaus . It is more likely, however, that the latter feature is derived, like many other characters: long skull and face creating a long mandibular diastema, very posterior choanae, ventrally inflated mastoid wall, indistinct tensor tympani fossa, complex post-cruciate sulcus in the brain, loss of parastyle on P4, procumbent ventral incisors, shape of m1 trigonid with a mesially located protoconid and short paraconid, and a proximal femur with a weak trochanter and flat caudal side with almost no trochanteric fossa. Mydaus lacks the characters, listed above, that define the Mephitini .

CONCLUSION

The monophyly of modern and Pleistocene American forms is strongly supported, and they can be called Mephitini . The identity of their sister taxon is more debatable. Overall skull shape suggests Promephitis , but this similarity does not hold if the skull shape of Mydaus is autapomorphic, as are many of its characters. We believe instead that the more derived brain morphology, slender zygomatic arch and related changes in masticatory musculature, and shallow subarcuate fossa, unite Mydaus with the Mephitini , as Mephitinae ( Fig. 4 View FIG ). Regarding Promephitis as the sister-group of the Mephitini implies convergent brain evolution between the latter and Mydaus . Because of the retention of a large protocone and absence of hypocone, we exclude Buisnictis and Martinogale from the Mephitidae ; they might, however, represent the sister-group of this family.

| MNHN |

Museum National d'Histoire Naturelle |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Promephitis lartetii Gaudry, 1861

| Geraads, Denis & Spassov, Nikolaï 2016 |

Promephitis hootoni Şenyürek, 1954: 281

| SENYUREK M. S. 1954: 281 |