Sminthopsis dolichura, Kitchener, Stoddart & Henry, 1984

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602879 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FF9C-2472-FF13-F3360D3F0A7B |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Sminthopsis dolichura |

| status |

|

Little Long-tailed Dunnart

Sminthopsis dolichura View in CoL

French: Dunnart de Buningonia / German: Kleine SchmalfuRbeutelmaus / Spanish: Raton marsupial pequeno de cola larga

Taxonomy. Sminthopsis dolichura Kitchener, Stoddart & Henry, 1984 View in CoL ,

6 km SSE of Buningonia Spring, 32° 28’ S, 123° 36’ E, Western Australia, Australia. GoogleMaps

In his major (1981) revision of Sminthopsis, M. Archer not only recognized twelve species of dunnart but also drew attention to several discrete populations and the fact that most recognized species exhibited geographical variation that may constitute different species. Subsequent electrophoretic and direct DNA studies have supported this, and today Sminthopsis is the most speciose genus of living dasyurid marsupials (with 19 species). Along with its close relatives Antechinomys (one species), Ningau: (three species), and Planigale (five species) constitutes the clade Sminthopsinae . Nevertheless, a recent genetic phylogeny (several mitochondrial and nuclear genes) failed to support monophyly of the genus Sminthopsis with respect to Antechinomys and Ningaui . There were three deeply divergent clades of Sminthopsis . In the first, S. longicaudata was sister to A. laniger (an alliance also obtained from previous morphological analyses where there was good reason to include Antechinomys within Sminthopsis and also to link it with S. longicaudata ). The second clade comprised the traditional morphologically based Macroura Group:five Smunthopsis comprised a strongly supported clade, including S. crassicaudata , S. bindu, S. macroura , S. douglasi , and S. virginiae . This clade of five dunnarts was only a poorly supported sister to the three species of Ningaui (N. ridei , N. timealeyi , and N. yvonneae). The combined clade of five Sminthopsis and three Ningawi was itself positioned as a poorly supported sister to a well-supported clade containing the remaining species of Sminthopsis (13 species in the Murina Group). This large dunnart clade contained a well-supported sister pairing of S. archer: with a clade containing five species: S. murina , S. gilberti, S. leucopus , S. butler , and S. dolichura . In his landmark revision of dunnarts, in the case of S. murina, Archer considered variation to be clinal and synonymized S. murina albipes, S. murina fuliginosa, and S. murina tate: with S. murina . Nevertheless, he used these names to “qualify the form of the species occurring in the vicinity of the type locality or having the particular morphological form,” noting that use of these names was not to be interpreted as recognition of their subspecific status. M. Archer believed that S. murina “fuliginosa” occupied Western Australia and South Australia west of the Flinders Range; the typo-typical form was to the east of this Range up to c.28° S; S. murina “tater” was evidently restricted to north-eastern Queensland; and a fourth form, allied to S. murina “fuliginosa,” occupied Kangaroo Island, South Australia. Archer did not recognize S. murina albipes as distinct from the typical form. On further inspection, collections from south-western Western Australia gave rise to the possibility that some morphological variation noted by Archer, such as bodysize, presence or absence of cusps on various teeth, and molar row lengths, was not clinal but indicative of separate species. Thus in 1984, D. J. Kitchener and colleagues redefined S. murina and described four new species: S. dolichura , S. gilberti, S. griseoventer , and S. aitkeni , the first three of these species occurring in south-western Western Australia. The work of P. R. Baverstock and colleagues that same year concurred with these revisions on genetic (allozyme) grounds, noting a high level of genetic uniformity within species but not among species. Unfortunately, external similarity of S. dolichura to other species of Sminthopsis makes field identification difficult, particularly when dealing with subadults. Further taxonomic research is needed to clearly define various species and their distributions in this cryptic group. Monotypic.

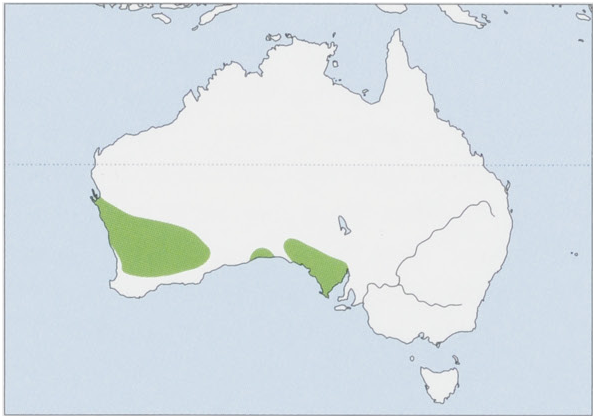

Distribution. S Australia, semi-arid and arid country in SW Western Australia and South Australia. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 6.3-9.9 cm (males) and 6.3-9.2 cm (females), tail 8-8— 10-9 cm (males) and 8:4.9-7 cm (females); weight 11-20 g (males) and 10-21 g (females). There is subtle sexual dimorphism for size. Dorsal fur of the Little Long-tailed Dunnart is pale to dark gray; head is pale gray with thin, black eye rings; face, cheeks, and patches behind ears are brownish; and ventral surfaces are whitish. Ears are long and bare. Tail is thin, about equalto, or slightly longer than, head-body length; dorsal surface of tail is pale gray, and ventral surface is white. The Little Long-tailed Dunnart differs from the Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart (S. Airtipes) and the White-tailed Dunnart (S. granulipes ) in lacking granular terminal pads or hair on interdigital pads on hindtoes. The Little Long-tailed Dunnart lacks prominent, dark head stripe or patch and fattened tail, which distinguish it from the Fat-tailed Dunnart (S. ecrassicaudata) and the Stripe-faced Dunnart (S. macroura ). Adult Little Long-tailed Dunnarts visibly differ from the Ooldea Dunnart (S. ooldea ), being larger and lacking a fat tail. The Little Long-tailed Dunnart differs from the Common Dunnart (S. murina ) in having a longertail, and dorsal fur is gray rather than brownish. The Little Long-tailed Dunnart can be distinguished from the Gilbert's Dunnart (S. gilberti) by its longertail and shorter ears and feet and from the Grey-bellied Dunnart (S. griseoventer ) in having a longertail and white rather than gray ventral fur.

Habitat. Prefer eucalypt woodlands, woodlands dominated by Acacia (Fabaceae) and Allocasuarina (Casuarinaceae) , shrublands, heath featuring myrtaceous and proteaceous species, and hummock grasslands with an overstory of low trees and low shrublands and woodlands (mallees). In one field study of Little Long-tailed Dunnarts in the Western Australian Wheatbelt, data suggested thatit prefers shrublands and woodlands with moderate-to-dense plant cover; it was relatively uncommon in rock sheoak ( Allocasuarina huegeliana ) and gimlet ( Eucalyptus salubris, Myrtaceae ) woodlands. The latter habitats are characterized by very open to nonexistent understory and a sparse (gimlet) or deep (sheoak) albeit compositionally simple litter layer. Studies on litter-dwelling invertebrates in such habitats have shown that abundances are generally lower in gimlet and rock sheoak habitats than in the others, particularly for larger invertebrates such as spiders and scorpions. Food availability and composition, and adequate cover,are likely important factors influencing habitat selection by the Little Long-tailed Dunnart. In their original description, Kitchener and colleagues noted that the Little Long-tailed Dunnart is widely distributed in the semi-arid savanna country of Western Australia and in South Australia west of the Flinders Ranges. The Little Long-tailed Dunnart occurs in all major vegetation and landform types except samphire vegetation on salt flats and paleo drainage lines. Such vegetation formations range from woodlands to open woodlands, usually dominated by Eucalyptus spp. but occasionally Acacia spp. and Casuarina spp. (Casuarinaceae) ; tall-to-low, open-to-closed shrublands and heaths, usually dominated by a mixed assemblage of myrtaceous and proteaceous plants but occasionally as a pure association of Melaleuca spp. (e.g. M. uncinata, Myrtaceae ) or Acacia spp. (A. resinimarginea, A. signata) or Casuarina spp. (C. campestris ); or spinifex ( Triodia scariosa, Poaceae ) with malice emergents. Substrate of such formations tends to comprise yellow, gray, and red sands, and gray-brown and red duplex soils incorporating clays and loams; occasionally, duplex soils have a pebble matrix. The type locality of the Little Long-tailed Dunnart is low E. salubris woodland, which almost lacks understory except for occasional low shrubs of Cratystylis conocephala ( Asteraceae ), Maireana sedifolia ( Amaranthaceae ), Scaevola spinescens ( Goodeniaceae ), Rhagodia spinescens, and Atriplex vesicaria (both Chenopodiaceae ). A-horizon of the soil at this locality is highly calcareous dark red loam with the clay content increasing with depth. Survey work in the Western Australian Wheatbelt and Goldfields indicates the Little Long-tailed Dunnart may have a much wider distribution than previously believed. Throughout its distribution,it is often common in areas in early stages of regeneration following fire. It becomes particularly abundant 3—4 years afterfire, at which time it may even temporarily displace other species of dunnarts.

Food and Feeding. The Little Long-tailed Dunnart is an active hunter, subduing beetles, crickets, spiders, and geckoes with rapid bites. Individuals captured in pitfall traps together with House Mice ( Mus musculus) have been known to kill the mice, devouring the head and hindquarters; it is unknown whether such predation occurs in the wild.

Breeding. Breeding of Little Long-tailed Dunnarts occurs in August-March; most females give birth to onelitter of up to eight young. Some females might rear two litters in a season, but this has not yet been confirmed in wild populations. Estrous cycle, gestation length, and developmental rates in Little Long-tailed Dunnarts are unknown (no detailed breeding studies have been undertaken in laboratory conditions). Young become independent of their mother at c.5 g and disperse widely into a range of habitats. Females typically commence breeding at 8-9 months old and will live up to c.2 years old. Males are capable of breeding at 4-5 months old and probably live shorter lives than females. One field study found that although there was no direct evidence of any female Little Long-tailed Dunnart raising a second litter in the same season, occurrence of occasional juveniles in early autumn in some years suggests polyestry.

Activity patterns. Little Long-tailed Dunnarts are nocturnal. During the day, they shelter in nests of dry grasses and leaves, constructed in a hollow log, grass tussock, or grasstree (Xanthorrhoea spp., Xanthorrhoeaceae ). In hummock grasslands, they may shelter in abandoned burrows of hopping-mice.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. One field study concluded that life history of the Little Long-tailed Dunnart is similar to the Common Dunnart from south-eastern Australia. There is high mobility (particularly in males) and transiency (¢.70% of males and ¢.60% of females), permitting the Little Long-tailed Dunnart to opportunistically invade new and postfire habitats. The Little Long-tailed Dunnart often has a sex ratio significantly biased toward males. Mobility appeared to be greater in the more arid Durokoppin part of the study area, perhaps reflecting a more variable and patchy distribution ofcritical resources such as food and shelter.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Little Long-tailed Dunnart has a wide distribution, presumably has a large overall population, occurs in numerous protected areas, and does not face any major conservation threats. Little Long-tailed Dunnarts appear to be common in suitable habitat. The Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) and domestic and feral cats probably prey on Little Long-tailed Dunnarts, particularly during spring and autumn when large numbers ofjuveniles are dispersing. Despite this, the Little Long-tailed Dunnart appears to be secure and under no immediate threat, but it is noteworthy that populations may fluctuate greatly in response to different seasonal conditions. The Wheatbelt habitat of Western Australia has contracted notably in the last century; the Little Long-tailed Dunnart is not found in agricultural lands, but it does occur in intervening areas.

Bibliography. Aitken (1972), Archer (1981a), Baverstock et al. (1984), Blacket et al. (2001), Dickman et al. (1995), Friend & Pearson (2008), Friend et al. (1997), Gould (1852), Iredale & Troughton (1934), Kitchener et al. (1984), Krajewski et al. (2012), Krefft (1867), McKenzie, van Weenen & Kemper (2008), Tate (1947), Thomas (1888b), Troughton (1965b), Waterhouse (1842).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Sminthopsis dolichura

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Sminthopsis dolichura

| Kitchener, Stoddart & Henry 1984 |