Palaeoxonodon sp.

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5374561 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/8C6F152B-C626-7745-F829-2CC2DFDF5E48 |

|

treatment provided by |

Marcus |

|

scientific name |

Palaeoxonodon sp. |

| status |

|

One of the difficulties in dealing with isolated molars results from their variability along the jaw. In the absence of associated upper molars for Palaeoxonodon and Amphitherium , the closest (in time) complete holotherian upper dentitions at our disposal for comparison are those from Guimarota: Henkelotherium Krebs, 1991 , Krebsotherium lusitanicum Martin, 1999 and Dryolestes leiriensis Martin, 1999 . These confirm the observations made on more recent dryolestoids (Morrison, Purbeck): the main characters (general shape, presence of a trigon ridge, degree of development of metacone, position of stylocone, labial cingulum) are constant along the series. Size and proportions vary, as well as the importance of the parastylar or metastylar lobes.

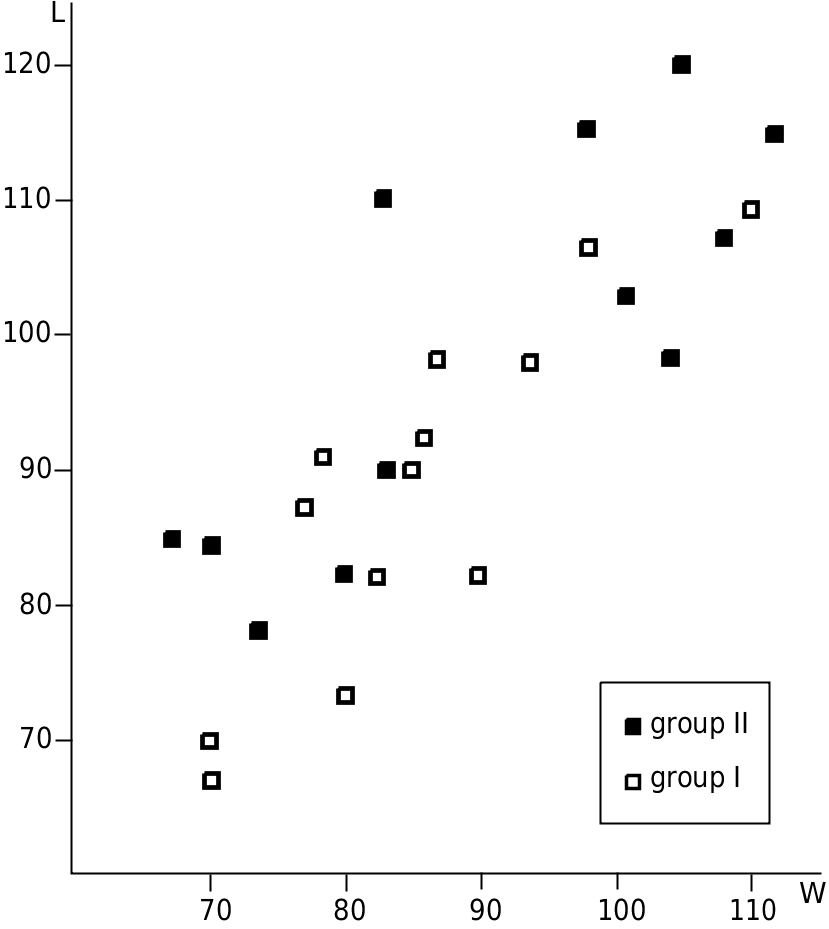

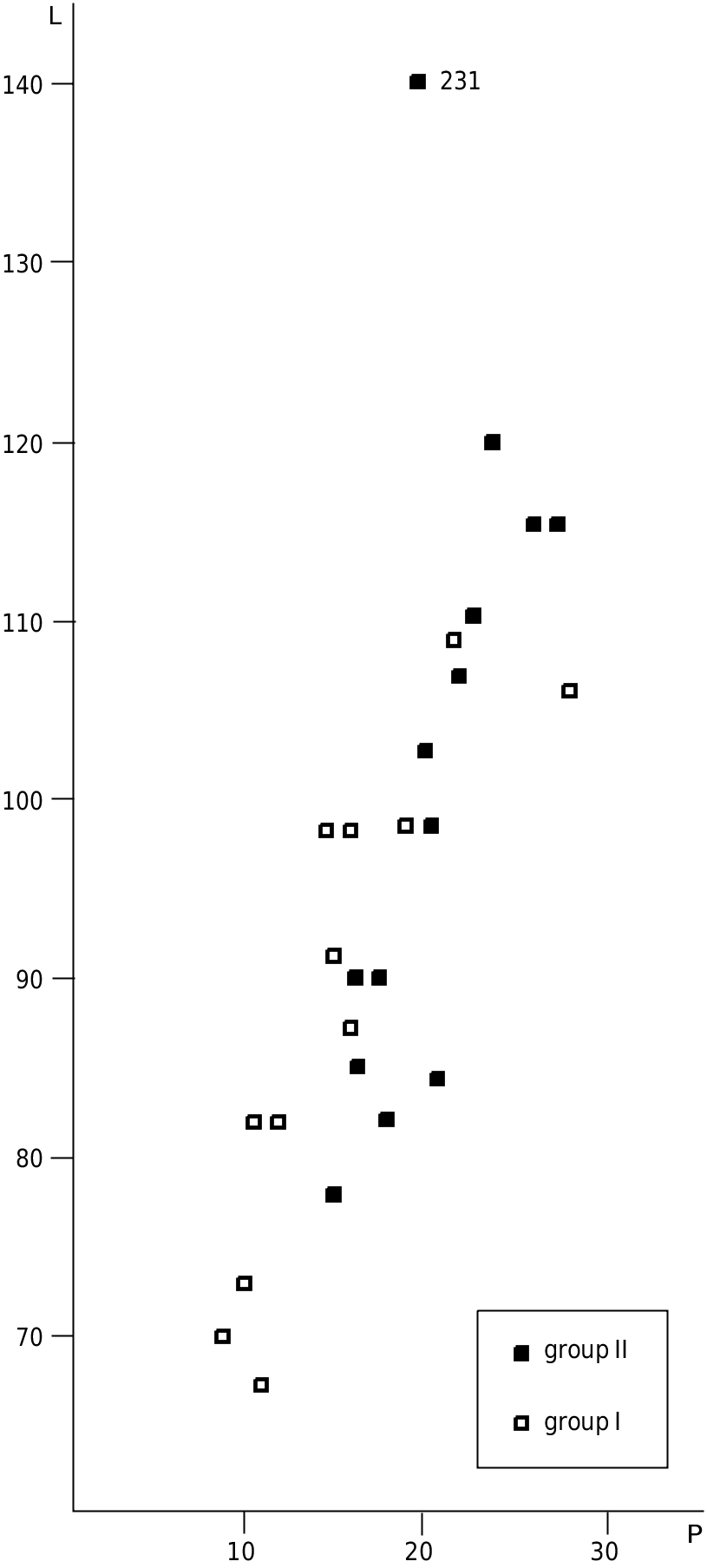

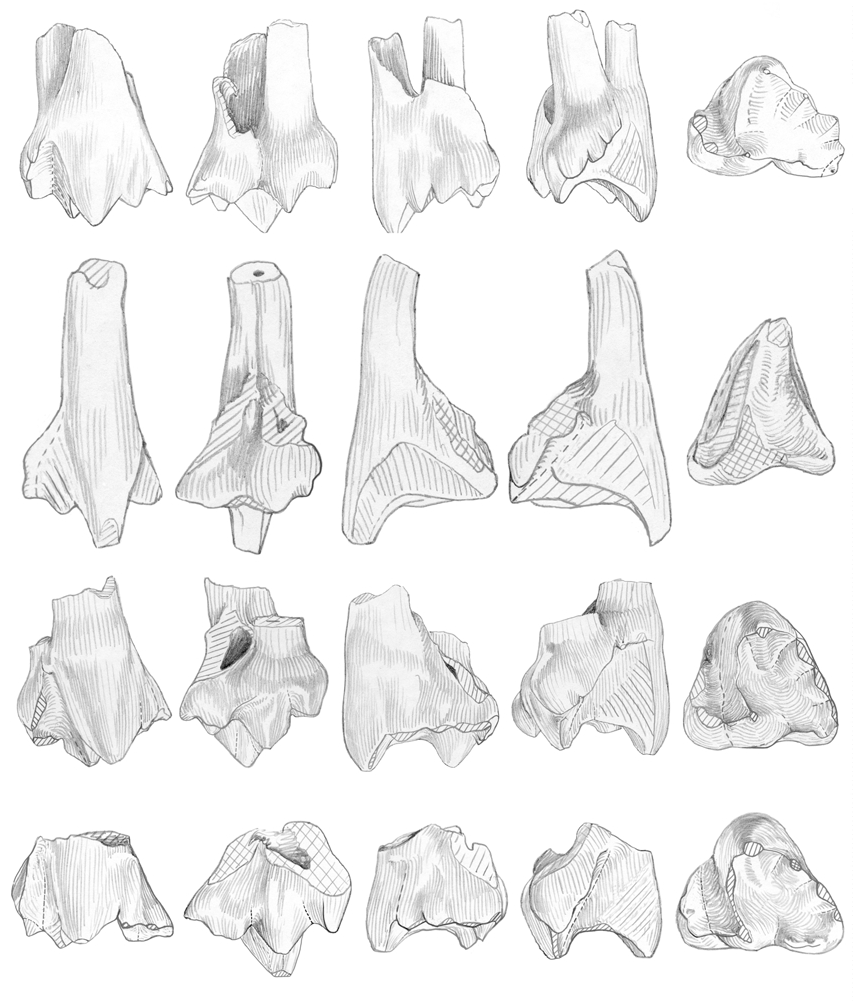

Among the Kirtlington holotherian upper molars, several groups can be recognized. I tentatively attribute two of these groups, which form the bulk of these molars, to Palaeoxonodon , the most abundant form among the holotherian lower molars. All of them have a labio-lingually wide trigon (Annexe, Tables 3, 4; Figs 12 View FIG ; 13 View FIG ).

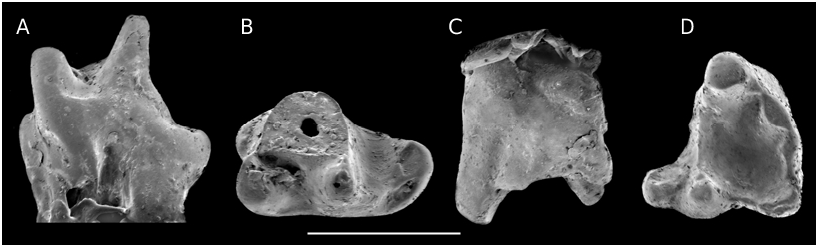

Group I ( Figs 9C, D View FIG ; 14 View FIG ; 19D View FIG )

BMNH J.146, J.524, J.749, J.754, J.792, M 36512 (figured by Freeman 1979: pl. 18, 1-3), right upper molars; BMNH J.137, J.392, J.436, J.636, M 36504 (figured by Freeman 1979: pl. 18, 4-5), left upper molars.

Questionably referred to group I: BMNH J.44, J.231, J.669, M 34994 View Materials , right upper molars; BMNH M 36526 View Materials (figured by Freeman 1979: fig. 2b, pl. 19, 4-6), J.25, left upper molar.

This first group (11 teeth) contains relatively short (antero-posteriorly) teeth with a weak median ridge, a labial parastyle crest oriented rather vertically, a usually straight preparacrista and straight or convex postparacrista+metacrista, both being nearly equal (except on J.749, Fig. 14B View FIG ). The paracone is sharp, and the metacone well distinct. A well individualized “c” cusp is always present, followed by a poorly defined metastyle. This point needs some clarification: the metastyle is the “cusp fitting against the lingual side of the parastyle of the following tooth” ( Butler 1978: 442). In fact, its identification is not easy, beyond Kuehneotherium and “ Eurylambda ”, where it appears as a sharp point of the posterior cingulum. Prothero (1981) and Martin (1999) figured schematically two small cusps, one posteriorly and one labially on the convex posterior border of the dryolestoid tooth; but on several dryolestoids, what I consider as the metacone is followed not only by “c” (not mentioned by Martin [1999] on his schema, Abb.7) but by a second often shorter but similarly shaped cusp (e.g., Krebsotherium lusitanicum M3, Dryolestes leiriensis M5, or Herpetairus Simpson, 1927 AMNH 101130, middle molar); a third cusp is even present in two cases. Then follows the curved posterior part of the tooth, on which metastyle cusps are more or less clearly projecting. On the sufficiently well preserved teeth from this group I from Kirtlington, the same situation is observed: the metacone is followed by one cusp, lower but wider labio-lingually (“c”), in fact in the shape of a curved crest rather than a cusp; then follows the rounded border of the tooth, bearing one or two cuspules, posteriorly and labially. It can also happen (e.g., J.749) that cusp “c” is shorter but doubled as in the cases mentioned above. The labial shelf bears a detectable individualized posterior stylar cusp only in two cases.

On this general scheme, several more features vary (Annexe, Table 4): a B’ formation ( Hu et al. 1997), again not in the shape of a sharp cusp but of a crestiform bulge projecting inside the trigon (very a b c d e similar to the situation in Spalacotherium- “ Peralestes ”), is present in four cases (and identifiable mostly when worn). This cusp is also present, though not named, in Nanolestes (see below). The ectoflexus is absent, weak or moderate. The stylocone is well developed, either terminal on the preparacrista or slightly posterior relative to it (but always linked to its labial extremity); it clearly dominates in height the parastyle in labial view. The latter is constituted of one or two elements. As mentioned above, the metastylar extension is variable, probably according to the position of the tooth along the jaw (like in “ Peralestes ”; J.146 is thus probably a last molar). There is only one case of an anterior cingulum (J.636, Fig. 14A View FIG ). When preserved, three roots can be counted.

The posterior face of the tooth is convex posteriorly, so that shear was not transverse; the metacone always has a distinct anterior face even if wear (facet A of Crompton 1971) is rarely detectable (BMNH J.295, J.436, J.392). On the teeth showing wear, the posterior face of the paracone ( Fig. 7 View FIG , facet 3) is the most frequently touched. More facets can be detected on the lateral face of the metacone and of “c”, the two (or three) cusps being either united or differently oriented. Only three teeth show wear on the anterior face of the paracone. The parastyle sulcus has the same nearly vertical orientation as the stylocone sulcus, one prolonging the other.

In the questionably attributed sample, J.231 ( Fig. 14D View FIG ) is a larger tooth with a nearly transverse posterior face; M 36526 View Materials is very worn, J.44 poorly preserved and J.25 has no preserved parastyle .

On M 34994 View Materials ( Fig. 9C, D View FIG ), the ridge is somewhat displaced anteriorly as in group II, but other characters are those of group I. Finally, J.669 also shares some characters with group II.

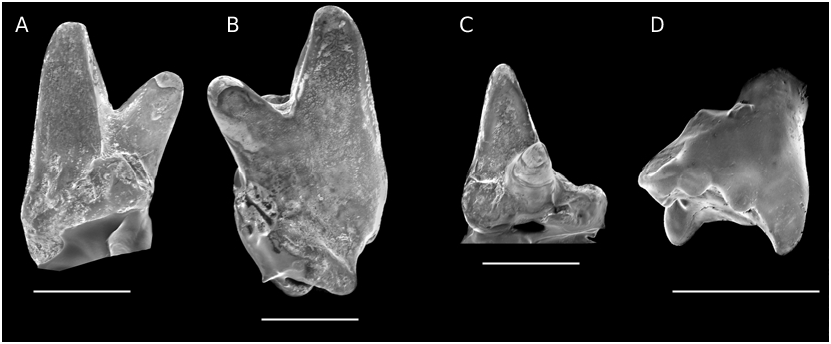

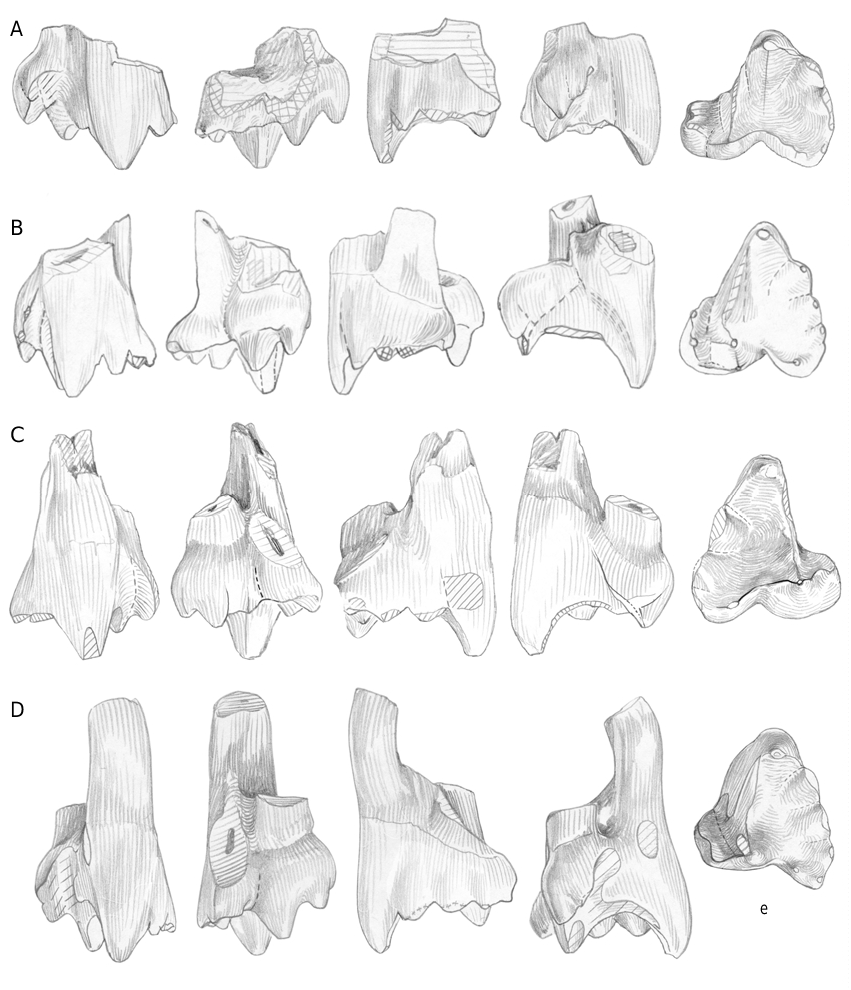

Group II ( Figs 15A, C, D View FIG ; 16A, B View FIG )

BMNH J.99, J.238, J.241, J.458, J.817, M 36532) (figured by Freeman 1976b: fig. 2a-b;

1979: pl. 9, 1-3; fig. 2a), right upper molars; BMNH M 36530, left upper molar.

Questionably referred to group II: J.32, J.506 (milk?), J.508, J.512bis, J.742, J.743, J.788, right upper molars; BMNH J.294, J.627, left upper molars.

This second group contains teeth with an anteriorly situated trigon ridge. The trigon is slightly more open, most often with a relatively lower paracone. Again, the preparacrista is usually straight and the postparacrista+metacrista straight or convex, but the former is clearly shorter than the latter (one exception), and provided in four cases with a distinct B’ bulge. The well developed parastyle is usually more lingually oriented. The stylocone remains strong but does not notably exceed the parastyle in height (one exception). The metacone and “c” are sharp cusps rather than crests and the latter is more often doubled than in group I. The metastylar area itself bears, in a few cases, one or two small and sharp cusps. A posterior stylar cusp is individualized in half the specimens. The stylocone and parastyle sulcus are here oriented at an angle. The posterior face of the trigon shows the same morphology as in the first group, not being transverse. When observable, one counts three roots.

As is apparent from the above description, variation is again considerable (Annexe, Table 4): the metastylar lobe is more or less extended, this being certainly related to the position of the teeth in the jaw. The parastyle (simple or double) is followed, in two cases (J.99, [ Fig. 15A View FIG ], and M 36532) by an anterior cingulum fainting lingually. Again, the ectoflexus is modest or strong, the stylocone is either terminal or displaced slightly posteriorly. According to Martin (1999: 7), this position differentiates Dryolestidae from Paurodontidae “stylocon direkt labial der Paracrista”; in fact it is distal on the holotype specimen of Comotherium Prothero, 1981 (unlike the figuration by Prothero 1981: fig. 2), a genus however classified by Martin in the Paurodontidae . Finally, several teeth have a short indentation labially between parastyle and stylocone.

Among the questioned teeth, J.742 ( Fig. 15C View FIG ) and J.788 (unlikely to represent the same specific taxon) are large teeth with also an anterior cingulum and a lingual cingulum as well; the stylocone is also slightly displaced lingually relative to the labial rim (this also occurs on J.743). Otherwise the main characters are the same as those mentioned above, with a particular relatively low paracone. All three possess a posterior stylar cusp. J.32 and J.512 are incomplete. J.506 may be a milk molar: it is very worn and has only two

A

B

C

D

a b c d

A

B

C

D

a b c d e a b c d

roots, the two being fused; but the trigon remains short antero-posteriorly. J.294 fits better with a milk molar; the trigon ridge is short, the posterior lobe extended, the ectoflexus strong and the parastylar wing extended transversely. J.508 ( Fig. 16B View FIG ) has a sharp paracone and narrow parastyle as in group I; but the ridge is not median, the parastylar cusp is relatively high and the metacrista cusps acute; moreover a cingulum overhangs the base of the parastyle and the stylocone. Finally, J.627 is a large tooth with the cristae and paraconal sulcus deeply worn.

The same type of wear as on group I prevails. But, due to a more marked convexity of the posterior face of the trigon, that affecting the posterior face of the metacone is more often distinct from that of “c”. Occlusion was thus of a similar type as in the first group (not completely transverse shear) though the rotatory movement must have been more accentuated: the parastyle sulcus is slightly more inclined and is angled downward along the stylocone, so that the tip of the parastyle is not worn and is even isolated by a crest.

COMMENTS

Again the question arises whether these two configurations (supposing the teeth included in each set are homogeneous) correspond to one or two distinct species: Martin (1999) cites the trigon ridge as varying within one unit of dryolestids, but this variation concerns more its expression than its situation. Other intraspecifically variable characters cited by Martin are, beside size and proportions, the stylocone development and the shape of the labial wall, variations also observed here. The length/width plot ( Fig. 12 View FIG ) does not reveal two sets of teeth as clearly as the same did for the lower molars: this relation may be more variable along the series than on the lower molars. Even if some teeth are difficult to assign to one or the other group, the differences mentioned above between the two groups seem to be sufficient to correspond to the two identified species of Palaeoxonodon . The so-called first group of upper molars may represent P. freemani n. sp., in which the masticatory movement would have been more vertical (parastyle sulcus more upright), the second P. ooliticus? Incidentally , doubts expressed by Sigogneau-Russell (1999) as to the attribution of BMNH M 36512 and M 36530 to this genus ( Freeman 1979) appear now, in the light of this new material, as unjustified.

Crompton (1971) had, after Mills (1964) and Clemens & Mills (1971), tentatively reconstructed the upper molar of Amphitherium and the occlusal pattern. If one excludes the relative proportions of the metacone and “c”, this reconstruction ( Clemens & Mills 1971: fig. 6A-B’) fits the material examined above. However, if a wear facet does persist on the anterior face of the metacone, no facet 4 is detectable on the talonid; this upper facet (on the metacone) would thus correspond to facet A and still occlude with that affecting the posterior side of the paraconid ( Fig. 7 View FIG ). The latter is in continuity with that detectable on the disto-labial extremity of the talonid of the preceding molar, and disposed at a different angle from facet 3 (labial face of talonid-paracone).

DISCUSSION

We can now come back to the question of the position of Palaeoxonodon-Amphitherium within Holotheria. Mills (1964: 129) compared the lower dentition of Amphitherium and Peramus and proposed that Peramus “should be transferred from the Paurodontidae to the Amphitheriidae ”. Similarly Kermack et al. (1968) placed Peramuridae in the suborder Amphitheria as opposed to the order Dryolestoidea . Crompton & Jenkins (1968: 455) argued that “the occlusion in Amphitherium was different from that in Kuehneotherium on the one hand and dryolestid pantotheres on the other” and concluded with the same classification as Kermack et al. (1968), a classification also adopted later by Freeman (1979). Crompton (1971) stated that Amphitherium represents a stage preceding the origin of a hypoconid (which would apply as well to Palaeoxonodon ). On the other hand, Clemens & Mills (1971: 108) concluded from their study of Peramus that “ Amphitherium and Peramus are representatives of different lineages”; however, this interpretation was based mostly on the comparison of the last lower premolar of Amphitherium with what they considered as the last premolar of Peramus but which is now interpreted as the antepenultimate premolar. Prothero (1981) presented several arguments to include Amphitherium in Dryolestoidea ; these have been discussed at length by Sigogneau-Russell (1999), who proposed that Amphitherium be considered the sister group of Zatheria, sharing with the earliest ones the presence of a distal metacristid and of an incipient talonid basin. McKenna & Bell (1997) do not give any argument for including the order Amphitheriida in the Dryolestoidea . Martin (1999) isolated Amphitherium from Zatheria (hence supposedly from Palaeoxonodon ) and linked it with Dryolestida on several lower molar characters: unicuspidate talonid (but so is it on several “peramuran” taxa, admittedly not considered by Martin), presence of six molars, paraconid forwardly inclined (not on M1 and hardly on M2 of Amphitherium M 36822), posterior lower molar root smaller than the anterior one (they are equal at least on the first molar of the same jaw); but no upper tooth character defines Martin’s Dryolestoidea ( Dryolestida plus Amphitherium , node 6, p. 4), Finally, Butler & Clemens (2001) implicitely excluded Amphitherium from Zatheria, while, in his later paper, Martin (2002: 346) considers Amphitherium as a representative of the “stem lineage of Zatheria”.

Now, if the upper molars described above are rightly attributed to Palaeoxonodon – and the near absence in the fauna of any Peramus -like molar sustains such an attribution – one is led to a contradictory situation between lower and upper molars, unless one admits that a long talonid is primitive for Trechnotheria. The lower molars are undoubtedly of a pretribosphenidan type (expanded talonid incipiently basined, distal metacristid, paraconal sulcus on metaconid), though the persistance of a lingual cingulum (as in Minimus ) and the presence of only one talonid cusp have to be considered as primitive; but the reduction of cusp e is again derived. This very peculiar configuration of the talonid both in amphitheriids and peramurids can hardly be considered as having developed twice (though this would only be one more example of parallel evolution in the dentition of Mesozoic mammals); it thus implies a close relationship between the two. On the upper molars, on the other hand, the presence of a cusp B’ was rightly considered as possibly primitive for spalacotheriids ( Cifelli & Madsen 1999); it definitely appears as the persistance, in amphitheriids, of a primitive trechnotherian character. Similarly, the “c” cusp is to be considered as a primitive heritage, being shared with some symmetrodonts and dryolestoids as well (that of peramurans may not be homologous). Finally the persistance of a wear facet A is plesiomorphic. But amphitheriid upper molars exhibit what are considered as dryolestoid apomorphies: widened trigon, trigon ridge, three roots, interlocking stylar region (however also present in some spalacotheriids and, for the last two, possibly Peramus ); these upper molars are at the same time devoid of “peramuran” features usually considered as derived: lingual position of the metacone, reduction of the stylocone, presence of lingual cuspules. This ambiguous situation might require a reconsideration of the polarity of the characters involved. In any case it emphasizes the insight of Blainville (1838) when coining the name Amphitherium .

Martin (2002) has recently published a new genus Nanolestes which he dubbed “a representative of the stem line of Zatheria”. As concerns the lower molars, no anterior or posterior view having been published, some details remain uncertain: did the anterior interlocking involve an e cusp? Does the “abc” cusp represent f? Is there a metacristid rather than a “cristid obliqua”? Moreover, the talonid is described as non basined but fig. 1A shows a double line on the talonid. The stereophoto of the occlusal view of the holotype seems also to show a diffuse lingual part in this area. But Martin wrote (in litt. 2002): “What you interpreted as a double line in my fig. 1A is the labial edge of the talonid cusp. There definitely is no incipient basin or double line present”.

As concerns the attributed upper molars of Nanolestes , Martin’s diagnosis (2002: 333) mentions “stylocone comparatively large and paracrista” (= preparacrista) “and metacrista” (= postparacrista+ metacrista) “separated into cusps and cuspules”. Large cusp “C (= ‘c’) between metacone and double-cusped metastyle. Additional cusp with two tips at the anterior border of the trigon near the base of the paracone” (cusp B’). If this doubling and degree of development of cusp B’ (a cusp not named by the author) represents undoubtedly an apomorphy of the genus (a smaller cusp B’ is also doubled at least on the last molar of “ Peralestes ”), the other features are quite comparable to what is observed in some trechnotheres and especially in Palaeoxonodon (especially group II). The two cusps labial to the metacone would represent a unique or double “c” cusp plus a metastyle. However, specific to Nanolestes would be the two unnamed cusps figured ( Figs 8 View FIG ; 9C View FIG ) between the paracone and metacone (though Martin’s description [2002: 341] says that the metacone follows “immediately” the paracone on the posteri- or border). Finally, a posterior stylar cusp seems also to have been present (“a small bulge with a tiny enamel cuspule”, Martin 2002: 341). The morphology of these upper molars is certainly closer to that of the dryolestoids than to that of Zatheria. The possible inclusion of Nanolestes into the amphitheriids rests on the clarification of uncertain points.

Meanwhile, Amphitheriidae may be diagnosed as follows, if one accepts the association proposed above of upper and lower molars: Cladotherian mammals whose lower molars have an elongated and incipiently basined talonid (1) with only one talonid cusp; presence of a distal metacristid (1). Lingual cingulid tends to disappear. Cusp e reduced or absent but a developed cusp f. Two subequal roots with a tendency to the predominance of the anterior root. Lower jaw slender, with an anteriorly situated mandibular foramen, an elongated Meckelian sulcus, a long symphysis. five premolars, five to seven molars. Upper molars relatively wide transversely; trigon ridge; presence of accessory cusps on the anterior and posterior cristae (1); metacone not lingually situated; large stylocone. Three roots. Persistence of facet A during occlusion. (Characters listed (1) are derived relative to Dryolestida ).

None of these characters is exclusive to the family. There remains to account for an elongated and incipiently basined talonid in the absence of a corresponding upper cusp (protocone). The elongation encountered in the amphitheriid line at least could have developed as an answer to the elongation of the postparacrista+metacrista (and development of accessory cusps) on the upper molars, thus increasing the efficiency of the shearing function. In dryolestoids, the answer to this elongation of the crista was to increase the transverse dimension of the lower tooth, which also contributed to improving the shearing function of the molars. In the pretribosphenid line, the elongation of the talonid and individualizaton of talonid cusps had its counter part in the lingual situation and role of the metacone, anticipating the grinding function of the teeth.

The remaining holotherian lower molars from Kirtlington again display a rather elongated talonid, but the distal point of the latter does not surpass the level of the posterior root as is the case in amphitheriids; moreover they are devoid of a metacristid and the posterior trigonid face is transverse. Some have a complete lingual cingulum; others lack this feature.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |