Odiomarinae, Guinot, 2011

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.2732.1.2 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/6A1E8787-C451-FFF4-FF3D-CCB62E9AFC34 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Odiomarinae |

| status |

subfam. nov. |

Odiomarinae View in CoL nov. subfam.

Genera included. Amarinus Lucas, 1980 ; Odiomaris Ng & Richer de Forges, 1996 .

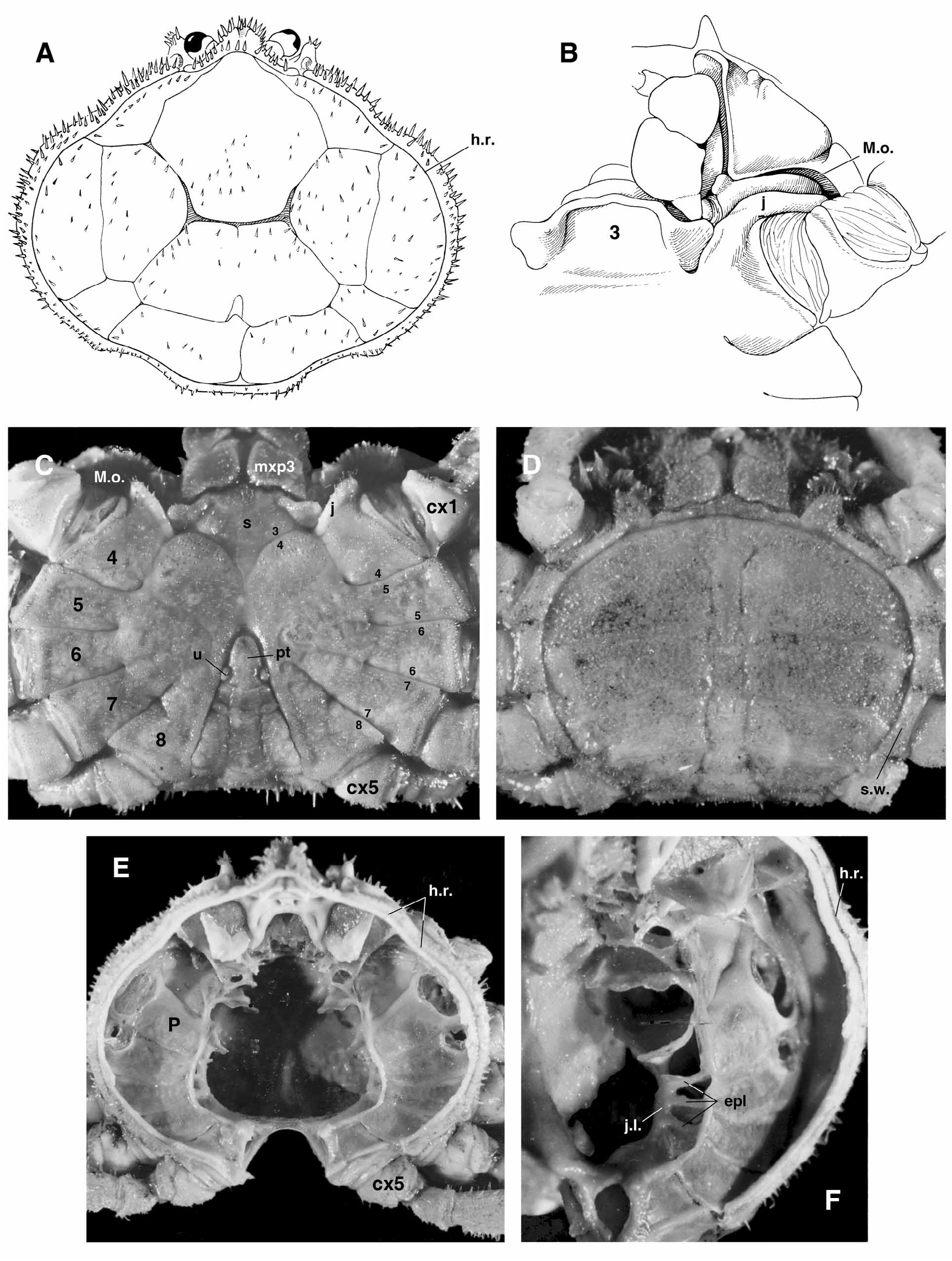

Diagnosis. Body dorsoventrally very flattened, cuticle thin. Carapace circular to oval, pear-shaped, with angles obtuse, rounded; posterolateral margin may be uneven, undulate, either unarmed or toothed. Dorsal surface flat, may be slightly concave; grooves varying from poorly to well defined, often not reaching lateral borders, with gastro-cardiac, thoracic grooves (terminology of Lucas 1980: fig. 1A). Hymenosomian rim continuous at base of rostrum. Rostrum unilobed, forming single, broad, spade-shaped lobe, directed downwards, base extending laterally over eyestalks, meeting postocular lobes. Eyestalks prominent. Antennules, antennae developed, usually visible dorsally. Epistome short. Pterygostomian lobe may be well marked. Mxp3 small but broad, operculiform; ischium approximately subequal to merus; palp slender. Thoracic sternum very wide; sternites 1–3 forming produced plate; sternites 4–8 medially fused; sutures 4/5–7/8 only lateral. Junction of sternite 4 with pterygostome pronounced, distinctly separating Milne Edwards openings from chelipeds. Chelipeds subequal, homomorph. Walking legs of moderate thickness, with sparse plumose setae; dactyli curved, without teeth or with one weak subdistal tooth on inner margin. Abdomens without fused somites (except for pleotelson) in both sexes; male abdomen triangular or with almost straight lateral margins parallel; presence of uropods showing as intercalated plates laterally at base of pleotelson, plates either prominent, moveable, or partially fused with pleotelson, or not well demarcated; pleotelson triangular or semicircular. Female abdomen with convex lateral margins, may form large, discoid plate, usually covering a brood cavity. G1 stout or more slender, spindle-shaped, curved base, remaining part nearly straight; distal portion with tip simple or with 2 or several lobes or processes; subterminal tufts of setae. Vulvae in unfused part of thoracic sternum, anteriorly displaced in intermediate position between inner ends of sutures 4/5, 5/6. Axial skeleton regularly compartmented, with parallel arrangement of phragmae in antero-posterior plane as well as above and below junction plate; sella turcica sole transversal binding.

Species included. Odiomaris Ng & Richer de Forges, 1996 (type species: Elamena pilosa A. Milne-Edwards, 1873 , by original designation), with two species: O. pilosus (A. Milne-Edwards, 1873) and O. estuarius Davie & Richer de Forges, 1996 .

Amarinus Lucas, 1980 (type species: Elamena lacustris Chilton, 1882 , by original designation), with eleven species: A. abatan Naruse, Mendoza & Ng, 2008 , A. angelicus ( Holthuis, 1968) , A. crenulatus Ng & Chuang, 1996 , A. lacustris (Chilton, 1882) , A. laevis (Targioni-Tozzetti, 1877) , A. latinasus Lucas, 1980 , A. lutarius Lucas & Davie, 1982 , A. paralacustris ( Lucas, 1970) , A. pristes Rahayu & Ng, 2004 , A. pumilus Ng & Chuang, 1996 , A. wolterecki (Balss, 1934) (see below).

For the distinction of the two genera, see Ng & Richer de Forges (1996: 271, figs. 5–7).

Ecology and geographical distribution. Both Odiomaris ( Ng & Richer de Forges 1996, 2007; Guinot & Richer de Forges 1997; Marquet et al. 2003; Juncker & Poupin 2009) and Amarinus ( Chilton 1915, as Halicarcinus pro parte; Walker 1969, as Halicarcinus ; Melrose 1975, as Halicarcinus pro parte; Lucas 1972, as Halicarcinus pro parte; 1980; Lucas & Davie 1982; Wear & Fielder 1985; McLay 1988; Chuang & Ng 1994; Towers & McLay 1995; Ng & Chuang 1996; Davie 2002; Johnston & Robson 2005) inhabit inland freshwaters: rivers and streams with rapid currents, swamps, at an altitude of 1600 m in New Guinea for A. angelicus ( Holthuis 1968: 112, as Halicarcinus ), and may be sometimes confined to lakes in New Zealand ( Lucas 1980; McLay 1988). They also inhabit low salinity waters in estuarine environments, having wide tolerance to salinities (e.g., A. abatan , see Naruse, Mendoza & Ng 2008). The presence of odiomarines in marine waters is questionable (see below). Amarinus is known from the Indo-West Pacific region: Philippines, Sulawesi, New Guinea, New Caledonia; mostly from Australia (mainland and islands); and New Zealand ( McLay 1988). Odiomaris appears to be endemic to New Caledonia ( Ng & Richer de Forges 1996, 2007), in rivers with rapid currents (G. Marquet, pers. com).

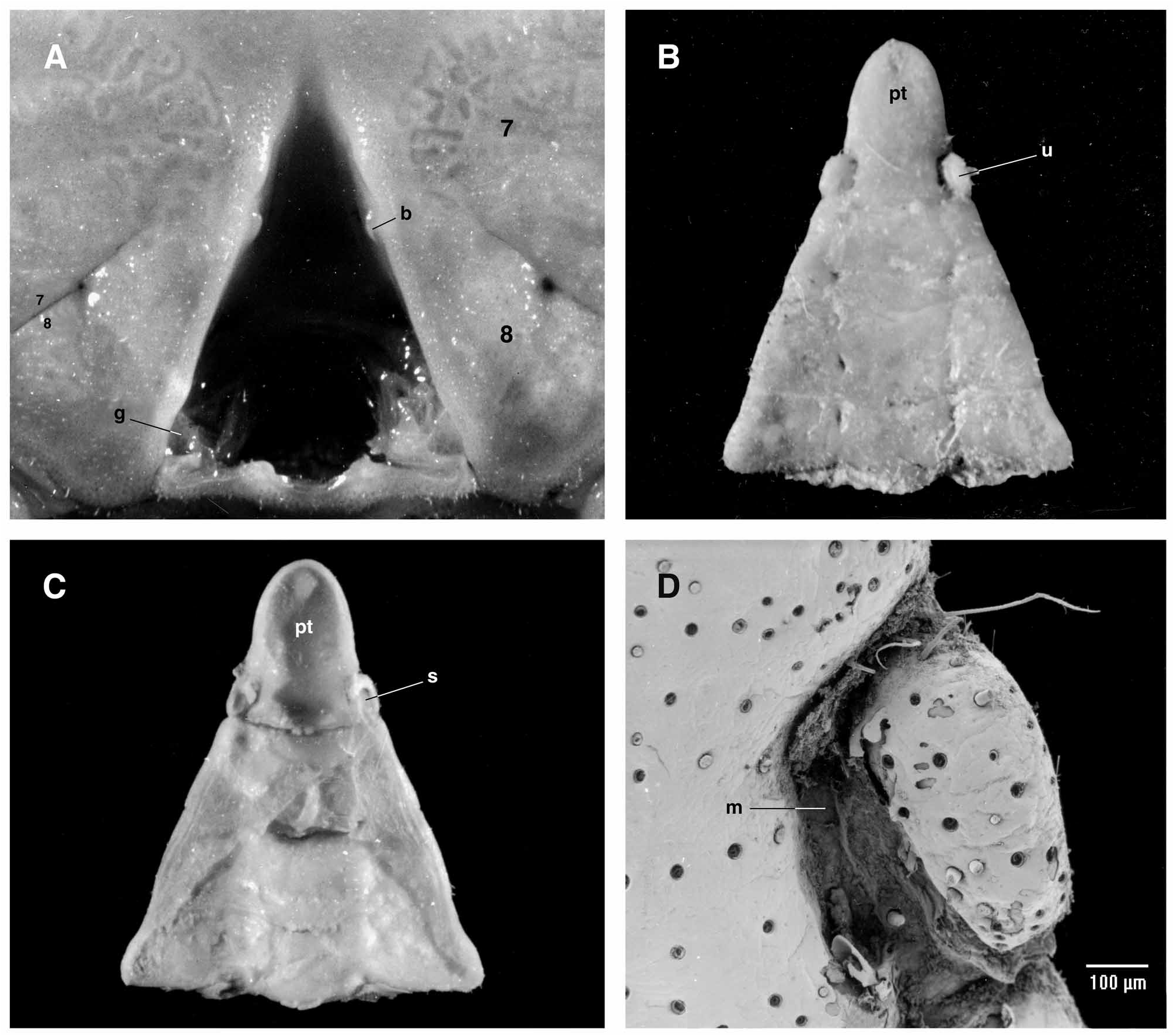

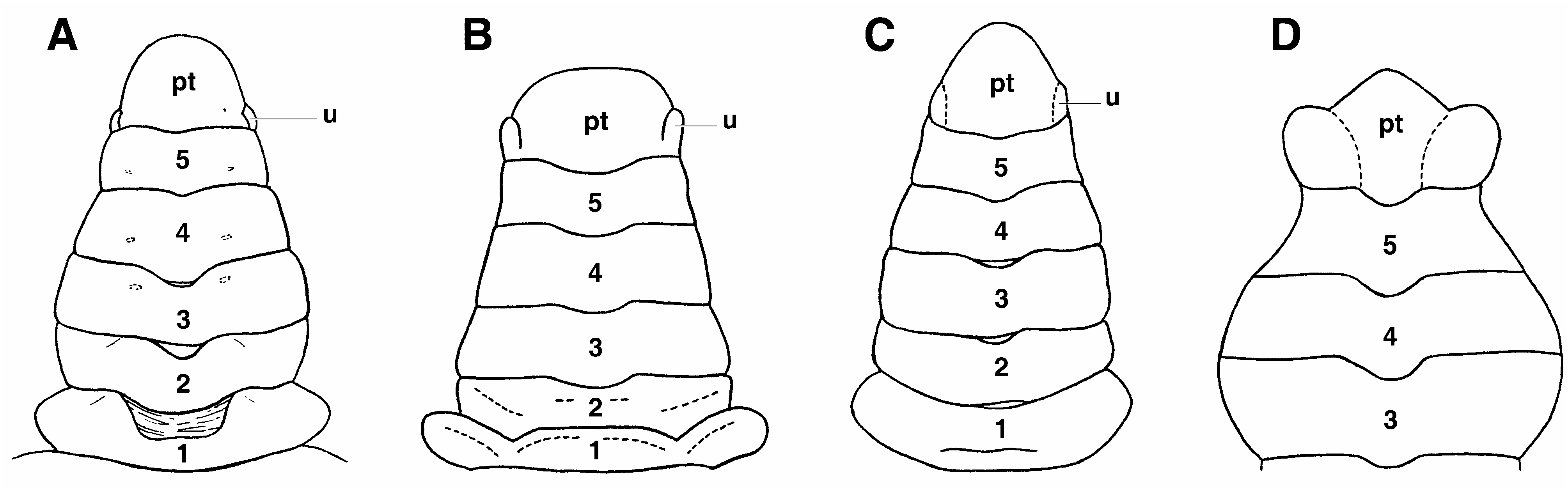

Remarks. The most significant trait of the Odiomarinae nov. subfam. is the presence of abdominal platelets on the male abdomen that are homologous to the dorsal vestigial uropods found in the Dromiidae De Haan, 1833 , as already suggested by Holthuis (1968: 115) (see Discussion). The odiomarine uropods, located on each side of the pleotleson’s base since the sixth abdominal somite is fused to the telson (pleotelson) as in all Hymenosomatidae , are moveable or, if they are not articulated, remain variously demarcated ( Figs. 1C View FIGURE 1 , 2B–D View FIGURE 2 , 3A–C; A View FIGURE 3 . Milne- Edwards 1873: pl. 18, fig. 6b; Holthuis 1968: fig. 1d, as Halicarcinus ; Lucas 1980: fig. 7A–D; Lucas & Davie 1982: fig. 9e; Ng & Chuang 1996: figs. 2D, 3E; Davie & Richer de Forges 1996: fig. 2C; Ng & Richer de Forges 1996: fig. 7B; Guinot & Richer de Forges 1997: figs. 4B–D, 6B–E; Guinot & Bouchard 1998: fig. 27; Rahayu & Ng 2004: fig. 2E; Naruse, Mendoza & Ng 2008: fig. 1e). The broad abdomen of the mature female is devoid of intercalated platelets ( Fig. 1D View FIGURE 1 ).

The vestigial uropod at the pleotelson’s base of the male abdomen is ventrally excavated in a deep socket, externally bordered by a thickened calcified margin and delimited by an articulating membrane ( Fig. 2C View FIGURE 2 ). This socket is used as the complementary part of a “button” located on the thoracic sternite 5 ( Fig. 2A View FIGURE 2 ), as usual in the Eubrachyura. Such platelets have so far not been reported in any Eubrachyura. Their persistence, or survival, in the Hymenosomatidae is evidence of the retention of an ancestral structure in a very ancient lineage. Odiomarinae nov. subfam. receives Amarinus and Odiomaris , which can be regarded among the more primitive hymenosomatids. The remaining genera are provisionally included in the Hymenosomatinae MacLeay, 1838, pending complete revision of the family in progress.

The plesiomorphic characters of Odiomarinae nov. subfam. include the male and female abdomens without fused somites (except for pleotelson), thus consisting of six elements (namely the maximum of somites existing in Hymenosomatidae ); the thoracic sternum with anterior sternites forming a narrow, produced plate; the vulvae not much anteriorly displaced; the axial skeleton regularly compartmented, with parallel arrangement of phragmae in anteroposterior plane; and the G1 only curved in the proximal portion, then straight.

The taxonomy of the Hymenosomatidae , complicated by their small size, flat shape, and the often transparent carapace, has long been unstable. Despite recent investigations, some genera could be paraphyletic, and the placement of many species will need to be re-examined (e.g., see Ng & Chuang 1996). Provisionally, preferring a strict diagnosis of the Odiomarinae nov. subfam., the subfamily cannot accommodate for the moment all the species that show faintly delimited uropods. Amarinus , as listed by Ng et al. (2008: 108), already contains various patterns for the carapace lateral margin (unarmed, regular, only undulate, or toothed), rostrum (continuous or not with the dorsal surface of the carapace), male abdomen (triangular or suboval), and G1 (stout or slender, tip simple or with lobes and processes).

Amarinus wolterecki has a male abdomen with six articles, a unilobed rostrum, and a spindle-shaped G1, but shows ten teeth on the lateral margins of the carapace, a rostrum that is continuous with the dorsal surface of carapace, and a G1 with well-defined, twisted folds and a simple tip ( Holthuis 1968: 117; Ng & Chuang 1996: 12, fig. 3). Amarinus pristes , from western Papua, Indonesia ( Rahayu & Ng 2004: 91, fig. 2; see also Naruse, Mendoza & Ng 2008: 431), with a carapace having a serrated lateral margin, a triangular rostrum, and with a truncate G1, is closer to A. wolterecki than to the other species of Amarinus . Amarinus laevis , the Halicarcinus australis ( Haswell, 1882) of many authors, shows delimited uropods and a particular combination of characters: toothed lateral margins of the carapace, almost trifid rostrum, prominent antennal spines, truncate apex of the G1, chelae of large males with a sac between bases of fingers, i.e., a pulvinus ( Lucas 1980: 199, figs. 4C, 7A, 10D; Poore 2004: 393, figs. 119c, 121b, e, pl. 21f).

Some genera and species in which the uropods are not still recognizable could prove to also belong to the basal Hymenosomatidae possibly close to the Odiomarinae nov. subfam. One such case is Hymenicoides Kemp, 1917 . The trilobate pleotleson of the type species H. carteri Kemp, 1917 ( Kemp, 1917: fig. 21; Guinot & Richer de Forges 1997: fig. 4E; Naruse & Ng 2007a: 18) and of H. robertsi Naruse & Ng, 2007 , may be interpreted as having the uropods integrated into the pleotelson ( Fig. 3D View FIGURE 3 ; Guinot & Bouchard 1998: 685), with he inflated areas at the pleotelson’s base corresponding to the deep sockets functioning with the sternal buttons, as clearly shown by Naruse & Ng (2007a: fig. 1a, b). Hymenicoides shows several plesiomorphic features similar to those of Amarinus and Odiomaris , in particular the five-articulated abdomen plus the pleotelson in both sexes, and a weakly grooved carapace ( Naruse & Ng 2007a: figs. 2a, b, 4a, b 5c, d). Both H. carteri and H. robertsi have, however, narrow, pediform mxp3, thus separated by a wide gap ( Kemp 1917: fig. 16; Guinot & Richer de Forges 1997: fig. 3A; Naruse & Ng 2007a: fig. 4b), which is indicative of a primitive condition (a limb-like appendage is assumed to be the ancestral character state as shown by the most primitive homolodromioids and homoloids; see Guinot 1995; Guinot & Richer de Forges 1995), differing from the stout, operculiform mxp3 of Amarinus and Odiomaris ( Fig. 1B, C View FIGURE 1 ; Holthuis 1968: figs. 2a, b, 3a, as Halicarcinus ; Lucas & Davie 1982: figs. 8b, 9c; Ng & Richer de Forges 1996: fig. 6C, D, G; Davie & Richer de Forges 1996: fig. 1B; Guinot & Richer de Forges 1997: figs. 1D, 2D; Rahayu & Ng 2004: fig. 2B). In contrast to Odiomaris (with triangular abdomens) and Amarinus (abdomen with roughly parallel margins, weakly narrowing distally), in Hymenicoides the male abdomen is wider, with irregular margins, the female abdomen less oval, the rostrum absent or weak, and the stout G1 strongly bent in its distal half ( Kemp 1917: fig. 21; Naruse & Ng 2007a: figs. 2a, b, 4a, 5a–d). The location of the vulvae about at the level of the inner ends of sutures 5/6 ( Naruse & Ng 2007a: 22), instead of being more anteriorly projected as in many Hymenosomatidae , is also a plesiomorphic character of Hymenicoides (see below). Limnopilos Chuang & Ng, 1991 ( Chuang & Ng 1991: 364, fig. 1), a genus closely allied with Hymenicoides , should be examined concurrently with Hymenicoides . Hymenicoides and Limnopilos share several plesiomorphic characters, such as the pediform mxp3, the six-articulated abdomen in both sexes, the inflated areas at the pleotelson’s base of the male abdomen ( Naruse & Ng 2007a: 26). The pediform shape of the mxp3 of Hymenicoides and Limnopilos indicates a basal position in comparison to Odiomaris and Amarinus , the evolutionary rate being not the same for all the morphological characters.

There are also plesiomorphic characters in Cancrocaeca Ng, 1991 , in which the male and female abdomens have, as in the odiomarines, five freely articulating somites plus the pleotelson, the G1 is straight in its two distal thirds and has several distal processes and subterminal tufts of setae ( Ng 1991: figs. 6, 7; Ng & Chuang 1996: fig. 5f; Guinot & Richer de Forges 1997: fig. 9A; Naruse & Ng 2007a: 19; Naruse, Ng & Guinot 2008: fig. 1d, e). The uropods, however, are not visible externally. Ng (1991: 61) had pointed out that the closest genus to Cancrocaeca was Amarinus , although Cancrocaeca xenomorpha is a highly modified taxon because of its troglobitic habits (pale coloration, blindness, long walking legs).

A provisional hypothesis is that Hymenicoides and Limnopilos form, with Cancrocaeca , a sublineage very close to the Odiomarinae nov. subfam., the precise relationships remaining to be clarified. It should be noted that the vulva has an operculum in the known species of the three genera ( Ng 1991: fig. 4E; T. Naruse pers. comm.). In these three genera, the carapace is rounded and weakly grooved, the rostrum absent or very weak, the mxp3 narrow, and the male abdomen wide and subcircular. Inclusion of Hymenicoides , Limnopilos and Cancrocaeca in the Odiomarinae nov. subfam. should be only made in relation to the level of generality of the characters chosen to differentiate the other hymenosomatids in the future classification.

A few taxa assigned to different genera in the literature, such as some species of Elamenopsis A. Milne- Edwards, 1873 (see Naruse & Ng 2007b) and Elamena H. Milne Edwards, 1837 , are in need of a reappraisal. The status of E. truncata (Stimpson, 1858) is puzzling because, in addition to cryptic uropods, it has a G1 and mxp3 that are not substantially different from those of the Odiomarinae nov. subfam. (see Ng & Chuang 1991: fig. 30C, I, J).

Elamenopsis guinotae Poore, 2010 , shows some of the typically odiomarine characters, in particular the prominent uropods, six-articulated male abdomen, and spindle-shaped G1 ( Poore 2010: fig. 2c, d, b, table 1). Its marine habitat (in eastern Bass Strait at 14-15 m depth, Victoria, Australia), however, contrasts to the fresh or brackish environment of the abovementioned odiomarines. In any case, all its features are typical of Elamenopsis species as noted by Ng & Chuang (1996) and Naruse & Ng (2007b), some of them being very close to the odiomarines.

The status of Hymenosoma hodgkini Lucas, 1980 , from marine and brackish waters of Australia, and with demarcated uropods, deserves some preliminary remarks. The abdomen is “sculptured making segmentation difficult to distinguish”, thus the number of somites is uncertain, 4 and 5 may be fused according to Lucas (1980). It will be necessary to establish if the following characters allow its assignment to the odiomarines: G1 with a dense zone of denticles on abdominal side; pterygostomal lobe developed, clearly visible; third female abdominal somite with posterolateral bulges ( Lucas 1980: 169, 170, figs. 2E, 6H, 7I, 10B, C; Davie 2002: 246; Poore 2004: 395, figs. 120e, 121c, f). No specimens were unfortunately available for study.

Halicarcinus whitei (Miers, 1876) , endemic from New Zealand, was described by Melrose (1975: 74, fig. 33D) as having on the male abdomen a remnant of the suture separating the sixth somite from the telson, a character not confirmed by McLay (1988: 380). This stage, preceding the complete fusion of the last two abdominal elements and leading to the formation of the pleotelson, could well be the most plesiomorphic case of the male abdomen occurring in the Hymenosomatidae .

Halicarcinus bedfordi Montgomery, 1931 View in CoL , has a triangular abdomen as in Odiomaris pilosus View in CoL and O. estuarius View in CoL , but without visible uropods; its pointed, projecting rostrum and several others distinguishing characters ( Montgomery 1931: 425, pl. 27, fig. 3; Lucas 1980: 181, figs. 3A, 5E, 6N, 7G, 9E, F; Davie 2002: 245; Poore 2004: 394, fig. 120b; Rahayu & Ng 2004: 88) do not permit a clear assignment.

The Hymenosomatinae emend., which provisionally receives all the hymenosomatids other than the odiomarine genera, includes taxa with diverse shapes of carapace (varying from rounded to trapezoidal or triangular; rostrum varying from weak to much projected), male abdomen (composed of a variable number of fused somites) ( Guinot & Richer de Forges 1997: figs. 4, 5A–I), various types of female abdomens ( Guinot & Richer de Forges 1997: fig. 7), and a G1 usually with a strong curvature. As such, the Hymenosomatinae emend. appears to be paraphyletic. The reclassification of the group is currently under study.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Odiomarinae

| Guinot, Danièle 2011 |

Halicarcinus bedfordi

| Poore, G. C. B. 2004: 394 |

| Rahayu, D. L. & Ng, P. K. L. 2004: 88 |

| Davie, P. J. F. 2002: 245 |

| Lucas, J. S. 1980: 181 |

| Montgomery, S. K. 1931: 425 |