Gulella newmani, Bursey & Herbert, 2004

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.7909894 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7910326 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B187DC-FFF2-FFC1-FE73-FC2F085D4729 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Gulella newmani |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Gulella newmani View in CoL sp. n.

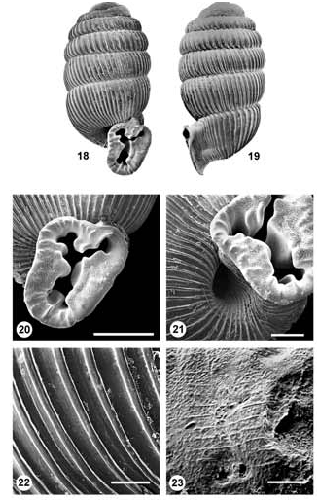

Figs 18–24 View Figs 18–23 View Fig

Etymology: Named after Noggs Newman, a long-standing member of the Board of Trustees of East London Museum, and founder and honorary life member of the Border Shell Club.

Diagnosis: Shell very small, sub-cylindrical; sculptured with strong axial ribs; peristome entire, disjunct from preceding whorl and forming a detached apertural tube, margin strongly flaring; apertural dentition seven-fold, but edge of lip also set with short ridges or small denticles; umbilicus relatively wide (width approx. 1.6 mm).

Description: Shell very small, sub-cylindrical; length 3.7–3.8 mm, width 1.8–1.9 mm, length:width approx. 2.0. Embryonic shell approx. 0.98 mm in diameter, comprising approx. 2.25 whorls; superficial sculpture eroded, but with traces of close-set microscopic spiral threads ( Fig. 23 View Figs 18–23 ); junction between embryonic shell and teleoconch distinct. Teleoconch comprising approx. 5 whorls; whorls convex, suture indented; sculptured by well-developed, weakly prosocline axial ribs, extending from suture to suture (54 on penultimate whorl); rib intervals lacking obvious microsculpture and with no evidence of spiral threads ( Fig. 22 View Figs 18–23 ). Peristome entire; terminal part of last whorl disjunct from preceding whorl and drawn out into a distinct, trumpet-like, apertural tube; tube descending somewhat such that aperture is orientated slightly downwards ( Fig. 19 View Figs 18–23 ). Aperture markedly constricted by teeth; dentition 7-fold ( Figs 20, 21 View Figs 18–23 ): 1) a well-developed parietal lamella, outer portion strongly oblique, its margin strongly sinuous, a small rounded swelling on left where lamella curves to run into aperture; 2) a compound, broad-based labral tooth with a broad, roundly spathulate, in-running slab at its centre, two smaller denticles at upper and lower extremities of labral base, upper one forming basal part of labral sinus; 3) an in-running ridge in centre of base, thicker and curving to left internally; 4) a similar but weaker ridge to left, at base of columella (and partly obscured by it); 5) a broad-based, compound, superficial columella tooth with a strong triangular tooth at its centre (opposite central element of labral tooth), and a smaller ridge-like tooth running inwards above this; 6) a deep-set, flat-topped columella lamella, largely obscured by superficial columella tooth (not visible in figures); 7) a minute, low denticle at junction of columella and parietal lip. Flared portion of aperture margin with additional ornamentation in the form of small tubercles in parietal region and short, low ridges elsewhere, set at right angles to lip edge ( Fig. 20 View Figs 18–23 ), 20–25 in total, fading in the region of labral sinus. Exterior of apertural tube indented in region of parietal lamella, labral base and columella tooth. Uppermost part of apertural tube, behind labral sinus, with a keel-like ridge running from flared edge of peristome to base of penultimate whorl; peristome edge indented slightly above parietal lamella and columella portion weakly concave. Umbilicus relatively widely patent (width approx. 1.6 mm), its opening round to ovate ( Fig. 21 View Figs 18–23 ). Shell translucent, uniformly milky-white when fresh.

Type material: Holotype: NMSA W568 View Materials /T1996, length 3.68 mm, width 1.84 mm. South Africa, Eastern Cape, Pondoland coast, Mbotyi (31º25.786'S: 29º43.563'E), forest at top of coastal escarpment, in leaf-litter under log, leg. M. Bursey & D. Herbert, 03/iii/2003. GoogleMaps

Paratype: ELM 13662 View Materials , found together with holotype .

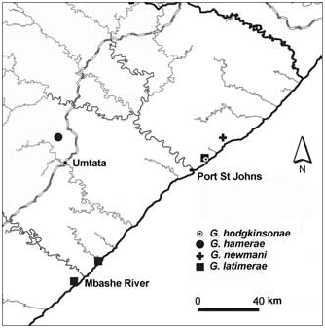

Distribution and habitat ( Fig. 24 View Fig ): Known only from the type locality which comprises tall coastal forest with large trees and an understorey of species including Buxus natalensis (Oliv.) Hutch. , Memecylon bachmannii Engl. and Stangeria eriopus (Kunze) Baill. ; in leaf-litter.

Remarks: Gulella newmani resembles G. latimerae in its entire, flaring peristome and detached apertural tube, but the latter is longer and more steeply sloping in G. newmani , off-setting the aperture to the right. In addition, G. latimerae is larger and broader, and lacks the short ridges and tubercles circling the aperture lip, a feature evidently unique to G. newmani within the southern African streptaxid fauna. The general form of the apertural dentition is similar in the two species, but there are small differences, most notably in the form of the superficial columella tooth which is more obviously tricuspid in G. newmani , and the larger basal ridge which in G. newmani continues to the aperture edge, but stops well short of this in G. latimerae .

CONSERVATION

All four new species are evidently narrow-range endemics, G. hamerae , G. dejae and G. newmani are each known from only a single locality, whereas G. latimerae appears more widely distributed, but even so, it is known only from isolated patches of coastal forest spanning a linear distance of no more than 110 km. In terms of the IUCN red-listing criteria ( IUCN 2001), the four species will undoubtedly qualify as threatened taxa and applications to this effect will be made after publication of their descriptions.

The forests of the Transkei region are considered to be of major conservation importance due to their rich biodiversity and high levels of endemism ( Cooper & Swart 1992; Cloete & Bosa-Barlow 2000; Van Wyk & Smith 2001; De Villiers 2002; White 2002). Cooper & Swart (1992) considered Nqadu Forest, the only known locality for Gulella hamerae , and the Pondoland coastal forests in which the other three species are found, to be of highest conservation priority. Mostly, such assessments have focussed on plants and vertebrates, but analyses of invertebrate distributions indicate similar foci of diversity and endemism in this region ( Herbert 2000; Bursey & Herbert 2001; Hamer & Slotow 2002; Herbert & Kilburn 2004). The four narrow-range endemics described herein are further evidence of this. In addition, they highlight the fact that the documentation of the invertebrate fauna of the region is far from complete.

Transkei forests, like most South African forests, have traditionally been utilised by local people as sources of natural products and for stock grazing. However, with reduction in forest extent and increased levels of utilisation, the sustainability of such practices has been compromised and they now represent a serious threat to the remaining forest patches ( Cooper & Swart 1992; De Villiers 2002; De Villiers & White 2002; Von Maltitz & Fleming 2000; Cocks et al. 2004; Lawes et al. 2004). Some of the forests in which these new Gulella species occur appear to be in relatively good condition with comparatively low levels of utilisation, e.g. the scarp forest at Mbotyi, whilst others are heavily impacted through the removal of forest products, trampling by cattle and invasion by alien plants, e.g. near the mouth of the Mntafufu River, the single known locality for G. dejae . The forests in Dwesa Nature Reserve, one of the localities for G. latimerae , once enjoyed total protection, but this is no longer the case ( Von Maltitz & Fleming 2000). Responsibility for management is in a state of flux ( Kuhn et al. 2002).

An additional concern is the fact that small forest patches have been considered to be of little value for long-term conservation ( Cooper & Swart 1992). However, such conclusions are drawn largely from the perspective of vertebrate animals, and do not take into consideration invertebrates of much more limited vagility, for which small forest patches may represent important refuges. An example of such is the new species of onychophoran discovered in a very small forest patch near Kokstad in KwaZulu-Natal (H. Ruhberg & M. Hamer pers. comm.). Kumqolo Forest, type locality for G. latimerae , is a small forest of less than 70 hectares in extent, yet it is known to contain at least six additional species of snail endemic to the Transkei coast, namely: Natalina beyrichi (Martens, 1890) , Gulella aprosdoketa Connolly, 1939 , G. pondoensis Connolly, 1939 , and three undescribed species belonging to the genera Archachatina , Sheldonia and Trachycystis . To dismiss the role of small forests in biodiversity conservation could have serious implications for species such as these. Similarly, assessments of the impact of exploitation practices have focussed mostly on larger animals and plants ( Geldenhuys 1997; De Villiers & White 2002), and activities that may have little impact on larger organisms, e.g. collection of fallen wood for fuel, may have profound effects for molluscs and other invertebrates ( Simelane et al. 2000). An action plan for the conservation of the indigenous fauna of Transkei forests is urgently needed.

| NMSA |

KwaZulu-Natal Museum |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |