Leptodactylus oreomantis, Carvalho, Thiago Ribeiro De, Leite, Felife Sá Fortes & Pezzuti, Tiago Leite, 2013

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3701.3.5 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:E25E2CF6-70F8-4198-B5C6-0ADE9DEB9121 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5613085 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03AF8791-2D43-FF99-458E-3A748E21FAD5 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Leptodactylus oreomantis |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Leptodactylus oreomantis View in CoL sp. nov.

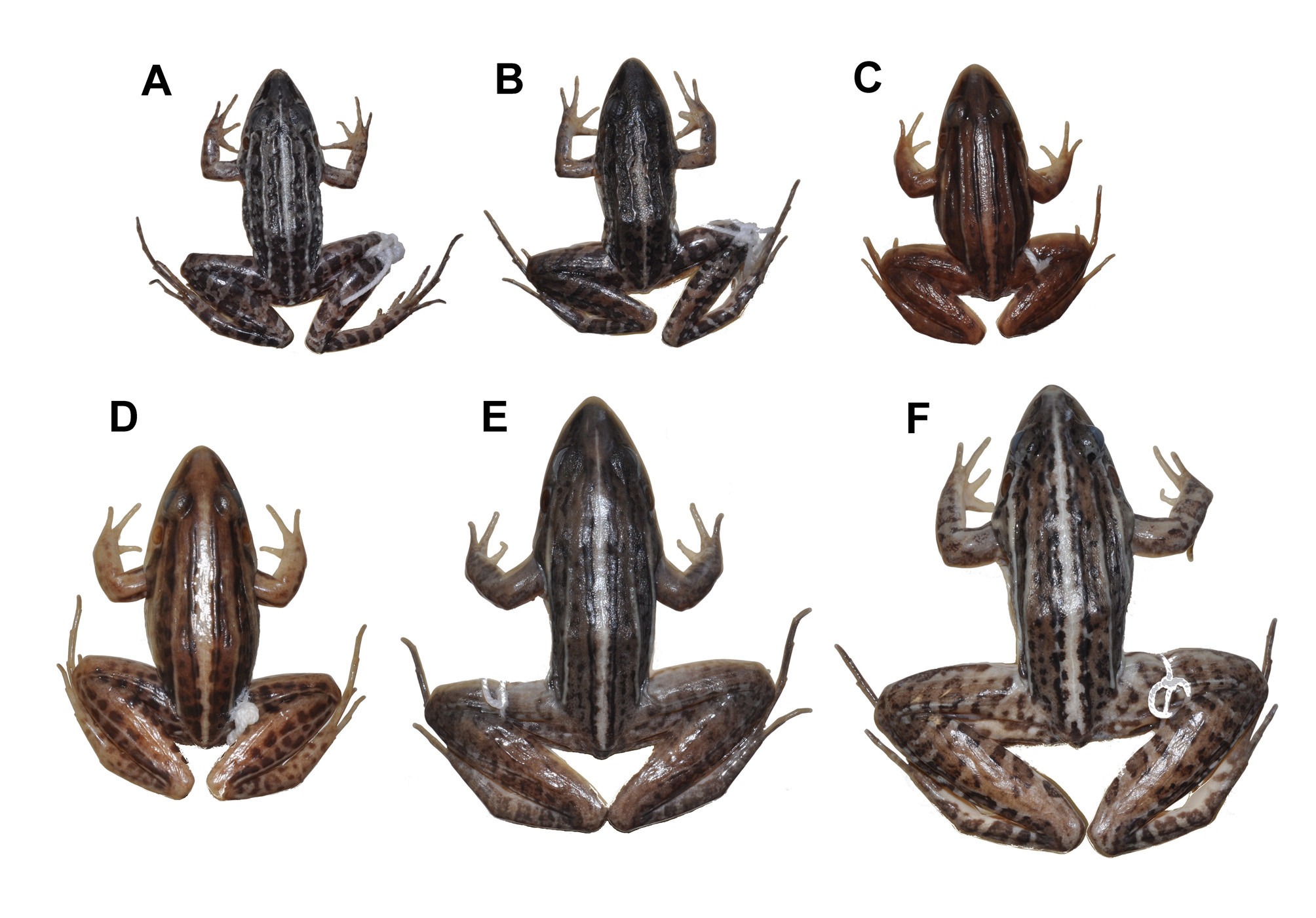

Figures 1–4 View FIGURE 1 View FIGURE 2 View FIGURE 3 View FIGURE 4

Holotype. UFMG 3825, adult male, collected at the Vale do Queiroz, Serra das Almas (13°31'23"S; 41°57'28"W, approximately 1575 m a.s.l.), Municipality of Rio de Contas, State of Bahia, northeastern Brazil, on 14 January 2010, by F. S. F. Leite, M. R. Lindemann, and R. B. Mourão.

Paratypes. Eleven adult males: UFMG 4444 (13°31'11"S; 41°56'59"W, 1540 m a.s.l.), UFMG 4461 (13°30'42"S; 41°56'58"W, 1461 m a.s.l.), on 10 January 2010, at the type locality, by F. S. F. Leite, M. R. Lindemann, and R. B. Mourão; UFMG 4355–4356 (12°45'58"S; 41°29'48"W, 1310 m a.s.l.), on 21 January 2010, Vale do Paty, Parque Nacional da Chapada Diamantina, Municipality of Mucugê, State of Bahia; UFMG 4361– 4363 (13°21'38"S; 41°16'34"W, 1295 m a.s.l.), on 29 January 2010, Municipality of Ibicoara, State of Bahia; all collected by F. S. F. Leite, M. R. Lindemann, and R. B. Mourão; UFMG 7888–7891 (13°08'12"S; 41°51'32"W, 1341 m a.s.l.), on 15 January 2010, Serra da Tromba, Nascente do Rio de Contas, Municipality of Piatã, by T. L. Pezzuti, L. O. Drummond, B. Imai, L. Rodrigues. Six adult females: UFMG 4443, 4445 (13°31'11"S; 41°56'59"W, 1540 m a.s.l.), on 10 January 2010, at the type locality, by F. S. F. Leite, M. R. Lindemann, and R. B. Mourão; UFMG 4260–4261 (12°46'38"S; 41°29'04"W, 1294 m a.s.l.), on 20 January 2010, UFMG 4294 (12°48'28"S; 41°27'55"W, 1300 m a.s.l.), on 21 January 2010, Parque Nacional da Chapada Diamantina, Municipality of Mucugê; UFMG 4332 (13°21'38"S; 41°16'34"W, 1295 m a.s.l.), Municipality of Ibicoara. Undetermined sex: UFMG 7948–7950 (13°13'01"S; 41°15'52"W, 1213 m a.s.l.), Serra do Sincorá, Parque Nacional da Chapada Diamantina, Toca do Vaqueiro, Municipality of Mucugê, on 19 January 2010, by T. L. Pezzuti, L. O. Drummond, B. Imai, L. Rodrigues.

Diagnosis. Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. is assigned to Leptodactylus (sensu Heyer 1969) by possessing a distinct tympanum, toes without webs, vomerine teeth present, and cutaneous folds on the tarsus; and assigned to the L. fuscus group by the following set of characters: 1) small body size; 2) toes lacking fringing or webbing; 3) adult males lacking thumb spines. The new species is diagnosed from the other 27 species of the L. fuscus group by the following combination of characters: 1) small-sized Leptodactylus (adult male SVL <35 mm); 2) slender body in dorsal view; 3) presence of six well-defined continuous dorsolateral folds; 4) absence of longitudinal light stripes on skin folds along the superior surfaces of thighs and/or shanks; 5) advertisement call composed of series of non-pulsed notes forming trills.

Comparisons with other species. Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. (adult male SVL 28.1–33.8 mm) is promptly diagnosed from all moderate-sized (adult male SVL> 35 mm <90 mm; sensu Heyer & Thompson 2000) species of the L. fuscus group: L. bufonius , L. cunicularius , L. cupreus , L. didymus L. elenae , L. fuscus , L. jolyi , L. labrosus , L. longirostris , L. mystaceus , L. mystacinus , L. notoaktites , L. poecilochilus , L. sertanejo , L. spixi , L. troglodytes , and L. ventrimaculatus (combined adult male SVL 36–65 mm) by its smaller body size (see Tables 1, 4). Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. can additionally be diagnosed from the following moderate-sized species ( L. albilabris , L. bufonius , L. caatingae , L. cupreus , L. elenae , L. fragilis , L. labrosus , L. latinasus , L. longirostris , L. mystaceus , L. mystacinus , L. notoaktites L. poecilochilus , L. troglodytes , and L. ventrimaculatus ) by the presence of six well-defined dorsolateral folds, whereas all species abovementioned have only one or two pairs of welldefined, ill-defined or no dorsolateral folds (see Table 4 View TABLE 4 ); from L. jolyi and L. sertanejo by the absence of light longitudinal stripes on skin folds along the superior surfaces of thighs and/or shanks (see figs. 2A–B, 2E–F).

TABLE 1. Morphological measurements (mm) of Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. type series (including the holotype) from the Chapada Diamantina, State of Bahia, Brazil. Mean±SD (minimum–maximum).

Among the small-sized species of the group, Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. is diagnosed from L. albilabris , L. caatingae , L. fragilis , and L. latinasus , by the presence of six well-defined dorsolateral folds, whereas all species abovementioned have only one pair of well-defined, ill-defined or no dorsolateral folds (see Table 4 View TABLE 4 ). The new species is diagnosed from L. gracilis and L. plaumanni by the absence of light longitudinal stripes on skin folds along the superior surfaces of thighs and/or shanks, by having a pointed snout in dorsal view, and by possessing a very slender body shape in dorsal view (see figs. 2A–B), whereas both aforementioned species have longitudinal stripes on skin folds along the superior surfaces of thighs and/or shanks, sub-elliptical snouts in dorsal view, and comparatively more robust body shape in dorsal view (see figs. 2C–D); from L. marambaiae , by the absence of dark longitudinal stripes on dorsum, and by the absence of a light stripe along the outer surface of shanks (see figs. 3A, D); from L. camaquara , by the presence of a light longitudinal stripe on the posterior surface of thighs (posterior surface of thighs with light spots on a dark-colored background in L. camaquara ; see figs. 3A, E). Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. can additionally be diagnosed from L. marambaiae and L. camaquara by having a pointed snout in dorsal view and by possessing a very slender body shape in dorsal view, whereas both aforementioned species have a sub-elliptical snout in dorsal view and slightly ( L. marambaiae ) or remarkably ( L. camaquara ) robust body shape in dorsal view (see figs. 3A, D–E). The new species is morphologically more closely related to L. furnarius and L. tapiti , all three species sharing the presence of a light vertebral pin-stripe, six well-defined sinuous and continuous dorsolateral folds, posterior surface of thighs striped, and pointed snout in dorsal view (figs. 3A–C). Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. is diagnosed from L. tapiti by possessing a discrete post-commissural gland (well-developed in L. tapiti ), and by possessing a comparatively more slender body shape in dorsal view (see figs. 3A, C). Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. (adult male SVL 28.1–33.8 mm; mean 31.2, SD = 1.3, N = 12) can be diagnosed from L. furnarius [adult male SVL 35.0– 37.5 mm, mean 35.9 (Sazima & Bokermann 1978); adult male SVL 31.0–39.0 mm, mean 36.5 (Heyer & Heyer 2004)] by its smaller body size (figs. 3A–B).

The advertisement call pattern sets Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. apart from almost all species of the L. fuscus group (see Table 4 View TABLE 4 ). For comparative bioacoustic data of the L. fuscus species group, see Heyer (1978), Bilate et al. (2006), Caramaschi et al. (2008), Giaretta and Costa (2007), Carvalho and Ron (2011), and Brandão et al. (2013). The advertisement call of Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. consists of a long series of non-pulsed notes forming trills. The same advertisement call pattern is already known for L. cunicularius and L. plaumanni (Sazima & Bokermann 1978; Kwet et al. 2001; Heyer et al. 2008; see fig. 6, Tables 3–4 View TABLE 3 View TABLE 4 ). Nonetheless, the new species can easily be diagnosed from L. cunicularius by having a pointed snout in dorsal view, a very slender body shape in dorsal view, continuous longitudinal dorsolateral folds (fig. 3A), and smaller body size (see Table 4 View TABLE 4 ), whereas L. cunicularius has a sub-elliptical snout in dorsal view, a remarkably robust body shape in dorsal view, interrupted longitudinal dorsolateral folds (see fig. 3F), and a remarkably larger body size (see Table 4 View TABLE 4 ); from L. plaumanni , by lacking light longitudinal stripes on skin folds along the superior surfaces of thighs and/or shanks [Heyer 1978 (reported as L. geminus Barrio , currently a synonym of L. plaumanni ); Kwet et al. 2001], whereas L. plaumanni possesses evident light stripes on skin folds along superior surfaces of thighs and/or shanks (figs. 2A– C). The advertisement call of L. ventrimaculatus is still undescribed, but its call structure is more similar to that of L. labrosus instead (S. R. Ron pers. comm.).

Assuming a close morphological relatedness among the new species, L. furnarius , and L. tapiti , we further diagnose L. oreomantis sp. nov. from L. laurae (Heyer 1978) , currently placed as a junior synonym of L. furnarius in Heyer (1983), an earlier available name prior to our description. The new species is diagnosed from L. laurae (mean adult male SVL 36.1 mm, SD = 2.3; holotype 40.4 mm) by its smaller body size (adult male SVL 28.1–33.8 mm; mean 31.2, SD = 1.3, N = 12). Furthermore, advertisement call pattern of L. laurae [T.R. Carvalho unpubl. data; recordings from the Municipality of Chiador, ca. 40 km to its type locality (Municipality of Juiz de Fora)] and L. furnarius (Sazima & Bokermann 1978) are identical (peep-like calls) in comparison to the trill-like call pattern of the new species.

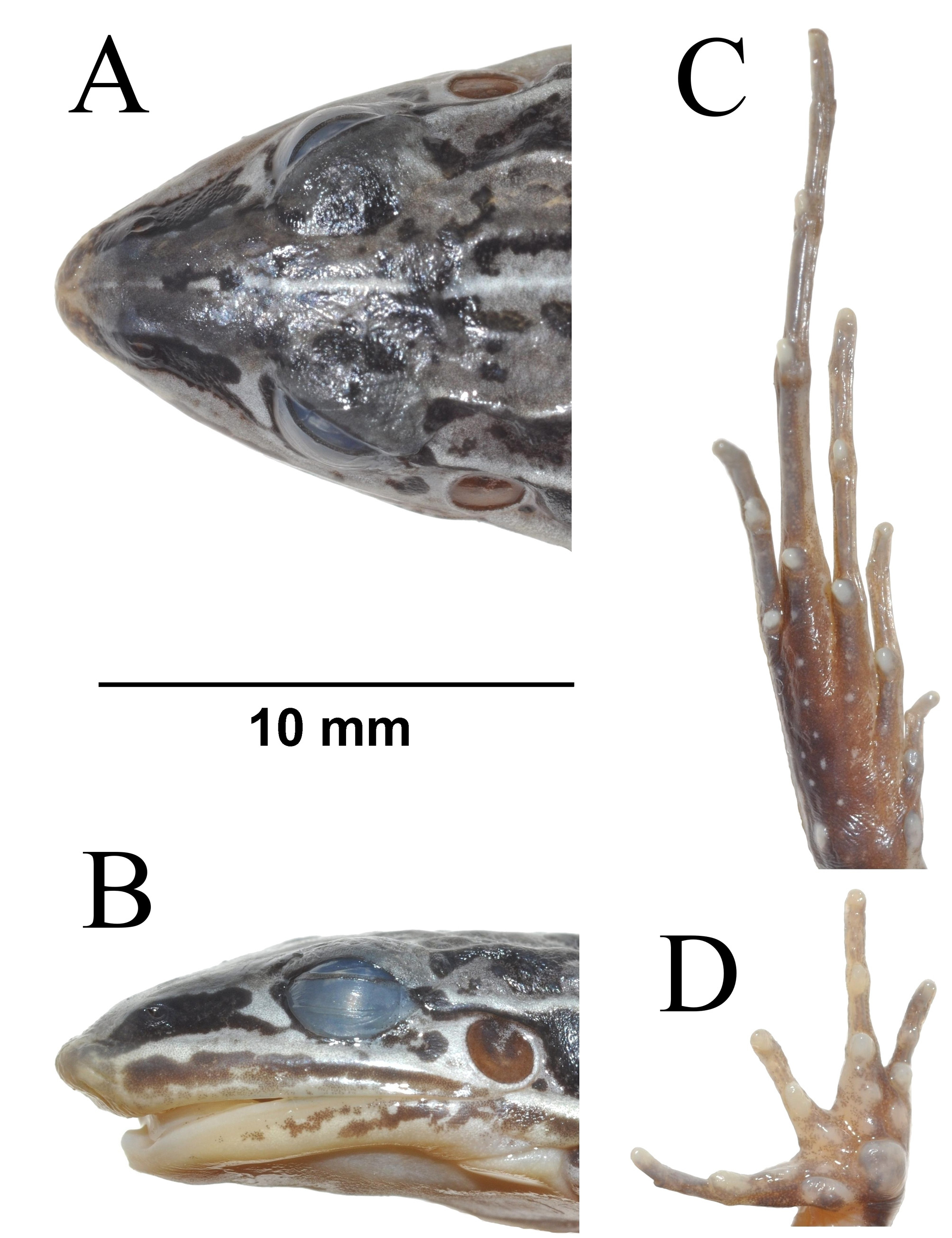

Description of holotype. UFMG 3825 (figs. 2A, 3A, 4). Adult male. Snout pointed in dorsal view (fig. 4A), acuminate in lateral view (fig. 4B) (sensu Heyer et al. 1990). Well-developed fleshy ridge on snout tip. Nostrils closer to the snout tip than to the eyes; canthus rostralis barely discernible; loreal region very slightly concave; upper eyelids smooth; supratympanic fold from the posterior eye corners to the base of arms; vocal sac subgular, expanded laterally, vocal slits present; vomerine teeth in two straight rows just behind choanae, almost connecting to each other. Relative finger lengths II ~ IV <I <III; finger tips rounded, not expanded, and with no webbing or fringing; inner metacarpal tubercle elongated; outer metacarpal tubercle ovoid, approximately double of inner dimension (fig. 4D). No thumb asperities or prepollex. Two undulating dorsal continuous dermal folds from interorbital region to groin; two dorsal and continuous dermal folds from the eyes to groin; two lateral dermal folds from the eyes to groin, interrupted in its last third. Discrete commissural glands just posterior to the jaw angle. Dorsal surfaces of body and limbs smooth, a few discrete granules scattered on the body. Dorsal surfaces of arms and legs with transverse stripes. Belly smooth. Posterior surface of thighs with a longitudinal stripe. Relative toe lengths I <II <V <III <IV; toe tips rounded, not expanded, and with no webbing, ridged laterally. Inner and outer metatarsal tubercles discrete, ovoid (fig. 4C). Tarsal folds absent. Heel, outer tarsi and sole of feet with scant minute tubercles.

Measurements of holotype. Morphometric characters (mm) and ratios (%) in relation to SVL (31.1 mm): HL 12.1 (38.9), HW 9.4 (30.2), ED 2.7 (8.7), TD 1.8 (5.8), END 3.0 (9.6), IND 2.6 (8.3), HAL 7.3 (23.5), TL 15.7 (50.5), SL 17.5 (56.3), FL 19.1 (61.4).

Color of holotype in preservative (figs. 2A, 3A). Dorsum with black anastomotic blotches on a brownish gray background. Limbs with black transverse stripes on a brownish gray background. Posterior surface of thighs with a light longitudinal stripe on a dark brown background. Cream stripes from inner metacarpal tubercle extending to two thirds length of tarsi. Cream vertebral pin-stripe with light stripes on the four external dorsolateral folds. Belly and throat cream, immaculate. Cream stripe from the snout tip to the base of arms. Outer tarsi and sole of feet scattered with white dots.

Variation. Specimens UFMG 4294, 4355–4356, 7888–7891 have dorsal surfaces of body and limbs darkened in preservative so that the blotches are not visible. Specimens UFMG 4261, 4332, 4355–4356, 4362, 4368, 7888– 7889, 7891, 7949–7950 have ventral surfaces of body (throat and belly) and limbs (thighs) with scattered black spots. Specimens UFMG 4136, 4261, 4294, 4356, 4362–4363, 4444, 7888–7891, 7949 have interrupted or no light stripes on dorsolateral folds. Female specimens have a more robust body. Specimens UFMG 4260–4261, 4294, 4332, 4363, 4443, 4445, 7890–7891, 7948–7950 have no well-developed shovel-like fleshy ridge on snout tip.

Color in life (fig. 1). In life, coloration is similar to that of specimens in preservative, but with vivid colors. Iris golden to silver with black vermiculation.

Geographic distribution. Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. is known from the Serra das Almas (Municipality of Rio de Contas), Serra da Tromba (Municipality of Piatã), and Serra do Sincorá (Municipalities of Mucugê and Ibicoara). These mountain ranges belong to the Chapada Diamantina, northernmost Espinhaço Range, State of Bahia, northeastern Brazil.

Natural history. Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. occurs in high altitude (altitudes ranging from 1213 to 1575 m a.s.l.) rock fields, called campos rupestres, a typical phytophysiognomy of the Espinhaço Range (fig. 5A). For a characterization of the campos rupestres flora, see Giulietti et al. (1987), Stannard (1995), and Vasconcelos (2011). For a characterization of the Espinhaço Range anuran fauna, see Heyer (1999), and Leite et al. (2008). Males call on meadows from the ground, mainly close to swallow temporary pools, and associated with small temporary streamlets without gallery forests (fig. 5B). The species is mainly active during the night, but in rainy or misty days males can also be heard during daylight. This species can easily be found (at least heard) during the beginning of the rainy season in the study region (December-January).

Etymology. The epithet oreomantis stands for ‘mountain frog’, from Greek (oreos = mountain; mantis = anuran/frog). A literal translation for Mantis would be ‘prophet’, but this term was also employed to refer to amphibians, since they represented the ‘weather prophets’ to ancient Greek civilization. This name is used as a noun in apposition.

Conservation. The extent of occurrence measured by a minimum convex polygon (EO, sensu IUCN 2001) of Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. has 3537 km 2. Within its EO, there are two Federal or State protected areas, the Parque Nacional da Chapada Diamantina (about 1519 km 2), which is strictly protected (equivalent to IUCN category II, IUCN 1994), and the Área de Relevante Interesse Ecológico Nascente do Rio de Contas (about 48 km 2), which is a sustainable use reserve (equivalent to IUCN category V), although the species is known based on observational occurrences only for the former. The species EO also contains very small reserves where it occurs (Parque Municipal Serra das Almas, Municipality of Rio de Contas at the type locality) or could potentially occur (Parque Municipal Sempre-Viva, Municipality of Mucugê, Parque Municipal do Espalhado, Municipality of Ibicoara, and Reserva Particular do Patrimônio Natural Itamarandiba, Municipality of Abaíra).

The species type locality (Serra das Almas) is broadly known by its singular floristic diversity (Stannard 1995), including several microendemics and ancient plant lineages (Ribeiro et al. 2012). This montane region is also the type locality of the hylid Bokermannohyla flavopicta (Leite et al. 2012) . However, despite its small protected area, the Serra das Almas currently has limited, if there is any, management and supervision. Therefore, disorderly land use and occupation, fire (from criminals and from agriculture or native pasture management for cattle breeding), and unregulated tourism are constant threats to Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. habitat. In assigning Serra das Almas as the type locality of an additional species, we expect to increase scientific and conservation concern to this region so as to arouse a more committed stance of the Brazilian government concerning the conservation and management of this unique biodiversity heritage. The creation of new and larger reserves is an imperative to hopefully meet a reserve system capable to ensure biodiversity representation.

Advertisement call. Four males recorded (N = 79 advertisement calls). Advertisement call ( Table 2 View TABLE 2 ; fig. 6) consists of series of 16–98 notes/call (mean 52.1; SD = 1.8) with duration varying from 0.74–5.09 seconds (mean 2.62; SD = 0.18) at a rate of 7–13 calls/minute (mean 9.1; SD = 2.0), and intercall interval from 1.22–9.71 seconds (mean 3.17; SD = 1.05), forming a trill-like pattern. Each call has an ascendant amplitude modulation at its beginning (first notes), and is composed of non-pulsed notes with up to 3 harmonics possessing a very slight or no ascendant frequency modulation, emitted at a rate of 353–644 notes/minute (mean 438.8; SD = 97.6). Duration of first notes varies from 13–22 ms (mean 16.6; SD = 2.7) with internote interval from 25–41 ms (mean 32.5; SD = 4.0), duration of median notes varies from 19–24 ms (mean 21.3; SD = 1.8) with internote interval from 26–37 ms (mean 31.4; SD = 2.2), duration of end notes varies from 17–24 ms (mean 20.3; SD = 1.7) with internote interval from 28–50 ms (mean 38.2; SD = 5.3). Dominant frequency peaks from 2.76–3.10 kHz (mean 2.97 kHz; SD = 0.03) and corresponds to the fundamental harmonic. The second and third harmonics are increasingly weaker in sound energy, peaking at approximately 6 kHz and 9 kHz, respectively.

Leptodactylus camaquara advertisement call. Eight males recorded (N = 119 advertisement calls). Advertisement call ( Table 2 View TABLE 2 ; fig. 7) consists of a non-pulsed signal with up to 3 harmonics possessing a slight ascendant frequency modulation, emitted at a rate of 94–120 calls/minute (mean 100.0; SD = 9.3), and at a rate of 1–3 calls/seconds (mean 2.2; SD = 0.4). Call duration varies from 0.16–0.27 seconds (mean 0.20; SD = 0.02) with intercall interval from 0.23–0.78 seconds (mean 0.34; SD = 0.04). Dominant frequency peaks from 2.25–2.44 kHz (mean 2.43 kHz; SD = 0.02) and corresponds to the fundamental harmonic. The second and third harmonics are increasingly weaker in sound energy, peaking at approximately 5.0 kHz and 7.5 kHz, respectively.

Additional remarks. The Espinhaço Range stands out for harboring a great diversity of the L. fuscus group (Heyer 1978), where 10 species have been already recorded ( L. caatingae , L. camaquara , L. cunicularius , L. furnarius , L. fuscus , L. cf. jolyi , L. mystacinus , L. troglodytes , L. mystaceus , and Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov.; F. S. F. Leite pers. comm.) within this mountain range, although only L. camaquara and Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. are in fact endemic to the Espinhaço Range. In the region of the Serra do Cipó, southern portion of the Espinhaço Range, State of Minas Gerais, seven species are sympatric ( L. camaquara , L. cunicularius , L. furnarius , L. fuscus , L. cf. jolyi , L. mystacinus , and L. mystaceus ) (Leite pers. comm.).

Since the compilation of the Espinhaço Range anuran endemics by Leite et al. (2012), who listed 33 taxa, three new species have been described: Corythomantis galeata (Pombal et al. 2012) , Proceratophrys redacta (Teixeira et al. 2012) , and Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. (present study). These authors did not include Bokermannohyla sagarana (Leite et al. 2011) in their checklist. Therefore, 37 anuran species should be considered endemic to the Espinhaço Range until the present time.

Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. represents the first species of the genus occurring restricted to montane rock fields (campos rupestres) of the Chapada Diamantina, northeastern Brazil. The other three species of the L. fuscus group assumed to be restricted or at least associated with montane field environments ( L. camaquara , L. cunicularius , and L. tapiti ) occur associated with mountain ranges of southeastern or central Brazil. Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. is the third species of the L. fuscus group with a trill-like advertisement call pattern, in which the advertisement call consists of well-defined note series. Interestingly, all three species of the L. fuscus group possessing the same trill-like advertisement call pattern are easily set apart from each other based solely on a general morphological approach: i) L. cunicularius is morphologically relatively similar to L. fuscus , which possesses a long whistle advertisement call pattern (Heyer & Reid 2003); ii) L. plaumanni is most morphologically similar or even identical to L. gracilis (see Kwet et al. 2001), which possesses a short whistle advertisement call pattern (Kwet et al. 2001); iii) Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. is morphologically more closely related to L. furnarius and L. tapiti , both possessing a peep-like advertisement call pattern (Heyer & Heyer 2004; Brandão et al. 2013). Based on the currently available phylogenetic hypothesis of the L. fuscus species group (Ponssa 2008), in which L. plaumanni and L. cunicularius were recovered in different clades, it is possible to assume that the trill-like call pattern should possibly have appeared at least two times independently, since we have not tested the phylogenetic position of Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. yet.

The advertisement call characteristics of Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. are very similar to those of L. cunicularius and L. plaumanni (see Kwet et al. 2001; Heyer et al. 2008; fig. 6). However, the advertisement call of L. cunicularius has a higher advertisement call rate (calls/minute), and a lower peak of sound energy in comparison with L. oreomantis sp. nov. (see Table 3 View TABLE 3 ). The obvious differences in emission rate among all three species could be attributed either to physical factors, as the temperature, or social context, for instance, the differential density of conspecific calling males at the time these species were recorded. In any case, addressing how temperature affected these recordings would depend on a larger sample of recorded individuals, as well as a wider range of temperatures so that we could apply proper statistical approaches. It worth stressing, despite some slight differences in quantitative bioacoustic variables, that these three taxa are not diagnosed from each other based solely on bioacoustic information available until the present moment. On the other hand, an unequivocal diagnosis under a morphological/morphometric approach of these species based on the combination of body size (small or moderatesized species), body shape in dorsal view (slender or robust), and the presence/absence of longitudinal stripes on skin folds along dorsal surfaces of thighs and/or shanks promptly supports their distinctiveness as independent lineages (see figs. 2A–C, and 3A, F), and represents a reliable line of evidence for the identification of both live and preserved specimens. Besides, there is no geographic distribution overlap among these three species, considering that Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. is restricted to montane rock fields of the Chapada Diamantina in northeastern Brazil, L. cunicularius is restricted to montane rock fields of southeastern Brazil (Heyer et al. 2008), and L. plaumanni occurs in southern Brazil and Argentina (Lima 2007).

* Bioacoustic data on L. geminus ( L. plaumanni junior synonym) were also included in the range of values.

* Given the wide range of SVL values, we assume that both male and female specimens are included. Gender was not mentioned (see Table 3 View TABLE 3 in Kwet et al. 2001).

FIGURE 7. (A) Oscillogram (20 seconds) of a section of 31 advertisement calls of Leptodactylus camaquara from the Municipality of Santana do Riacho, State of Minas Gerais; (B) Audiospectrogram (above) and corresponding oscillogram (below) detailing three advertisement calls (15th–17th calls delimited by a red rectangle outline) of the section of 31 advertisement calls of L. camaquara . Figures generated at 512 points resolution (FFT).

The advertisement call of L. camaquara was described in its original description (Sazima & Bokermann 1978). The bioacoustic data presented in the original description concerning the call structure demonstrated a slight ascendant frequency modulation, as well as the quantitative variables of call duration, intercall interval, dominant frequency (fundamental harmonic), and the presence of three harmonics are in compliance with our data.

TABLE 4. Summary of adult male size (value range), character states of dorsolateral folds, and advertisement call pattern for the species of the Leptodactylus fuscus group. Species with a trill-like advertisement call pattern are in bold type. ‘ Non-pulsed’ calls encompasses the remaining non-pulsed call patterns (e. g. short / long whistles and peep-like calls). Body size decimal numbers were rounded.

| Species SVL (mm) Dorsolateral folds L. albilabris 30–43 One pair | Call pattern Non-pulsed | Source Heyer (1978) |

|---|---|---|

| L. bufonius 52 No well-defined folds L. caatingae 32–37 Ill-defined or no folds L. camaquara 29–32 Six well-defined folds L. cunicularius 36–43 Six well-defined folds L. cupreus 49–57 One pair L. didymus 46–52 One pair | Non-pulsed Pulsed call Non-pulsed Trill Non-pulsed Non-pulsed | Heyer (1978) Heyer & Juncá (2003) Sazima & Bokermann (1978); Present study Sazima & Bokermann (1978); Heyer et al. (2008) Caramaschi et al. (2008); Cassini et al. (2013) Heyer et al. (1996) |

| L. elenae 38–46 One or two pairs L. fragilis 26–43 Ill-defined folds L. furnarius 31–39 Six well-defined folds L. fuscus 43 Six well-defined folds | Non-pulsed Pulsed call Non-pulsed Non-pulsed | Heyer & Heyer (2002) Heyer et al. (2006) Heyer & Heyer (2004) Heyer (1978); Heyer & Reid (2003) |

| L. gracilis 30–48* Six well-defined folds L. jolyi 45 Six well-defined folds | Non-pulsed Non-pulsed | Heyer (1978); Kwet et al. (2001) Sazima & Bokermann (1978) |

| L. labrosus 55 One or two pairs | Pulsed call | Heyer (1978); Carvalho & Ron (2011) |

| L. latinasus 28–38 Ill-defined or no folds L. longirostris 38 One or two pairs L. marambaiae 33–38 Six well-defined folds L. mystaceus 43 One pair L. mystacinus 44–65 One or two pairs L. notoaktites 47 One pair | Non-pulsed Non-pulsed Non-pulsed Pulsed call Non-pulsed Non-pulsed | Heyer (1978) Heyer (1978); Crombie & Heyer (1983) Izecksohn (1976) Heyer (1978); Heyer et al. (1996) Heyer et al. (2003) Heyer (1978); Heyer et al. (1996) |

| L. oreomantis sp. nov. 28–34 Six well-defined folds L. plaumanni 30–42* Six well-defined folds | Trill Trill | Present study Heyer (1978); Kwet et al. (2001) |

| L. poecilochilus 45 One or two pairs L. sertanejo 48–54 Six well-defined folds L. spixi 43 One pair L. tapiti 30 Six well-defined folds L troglodytes 49 No well-defined folds L. ventrimaculatus 50 One pair | Non-pulsed Non-pulsed Non-pulsed Non-pulsed Non-pulsed Pulsed call | Straughan & Heyer (1976); Heyer (1978) Giaretta & Costa (2007) Heyer (1983); Bilate et al. (2006) Sazima & Bokermann (1978); Brandão et al. (2013) Heyer (1978) Heyer (1978); Santiago R. Ron pers. comm. |

TABLE 2. Advertisement call variables of Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. from the Chapada Diamantina (Municipalities of Piatã and Rio de Contas), State of Bahia; and Leptodactylus camaquara from the Parque Nacional da Serra do Cipó (Municipality of Santana do Riacho), State of Minas Gerais. Mean ± SD (minimum – maximum). N = number of recorded specimens (number of analyzed calls).

| Bioacoustic variables Call duration (s) | Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. N=4 (79) 2.62±0.18 (0.74–5.09) | Leptodactylus camaquara N=8 (119) 0.20±0.02 (0.16–0.27) |

|---|---|---|

| Intercall interval (s) Notes/call Duration of first notes (ms) | 3.17±1.05 (1.22–9.71) 52.1±1.8 (16–98) 16.6±2.7 (13–22) | 0.34±0.04 (0.23–0.78) -------------- -------------- |

| First internote intervals (ms) Duration of median notes (ms) Median internote intervals (ms) | 32.5±4.0 (25–41) 21.3±1.8 (19–24) 31.4±2.2 (26–37) | -------------- -------------- -------------- |

| Duration of end notes (ms) End internote intervals (ms) Calls/minute | 20.3±1.7 (17–24) 38.2±5.3 (28–50) 9.1±2.0 (7–13) | -------------- -------------- -------------- |

| Calls/second Notes/minute Dominant frequency (kHz) | -------------- 438.8±97.6 (353–644) 2.97±0.03 (2.76–3.10) | 2.2±0.4 (1–3) 100.0±9.3 (94–120) 2.43±0.02 (2.25–2.44) |

TABLE 3. Comparative bioacoustic parameters (range of values) of the three species of the Leptodactylus fuscus group with trill-like advertisement call pattern (Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov., L. cunicularius, and L. plaumanni, and their respective sources).

| Bioacoustic variables* | Leptodactylus oreomantis sp. nov. (Present study) | Leptodactylus cunicularius Leptodactylus plaumanni (Heyer et al. 2008) (Kwet et al. 2001)* |

|---|---|---|

| Call duration (s) | 0.74–5.09 | 0.91–3.09 1.10–3.10 |

| Notes/call | 16–98 | 6–51 17–54 |

| Calls/minute | 7–13 | 15–19 -------------- |

| Dominant frequency (kHz) | 2.76–3.10 | 2.36–2.67 1.90–3.48 |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |