Sminthopsis ooldea, Troughton, 1965

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602913 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FF95-2479-FACC-F38607960224 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe (2022-06-01 12:15:38, last updated 2024-11-29 09:59:38) |

|

scientific name |

Sminthopsis ooldea |

| status |

|

Ooldea Dunnart

Sminthopsis ooldea View in CoL

French: Dunnart d’'Ooldea / German: Ooldea-SchmalfuRbeutelmaus / Spanish: Raton marsupial de Ooldea

Other common names: Troughton’s Sminthopsis

Taxonomy. Sminthopsis ooldea Troughton, 1965 View in CoL ,

Ooldea , South Australia, Australia.

Among the 28 recognized species of Sminthopsinae , phylogenetic relationships have been subject to morphological and molecular investigation. Notably, genetic-based phylogenies have failed to support monophyly of the genus Sminthopsis with respect to Antechinomys and Ningauwi. In the hypothesized phylogenies, there were three deeply divergent clades of Sminthopsis . In the first, S. longicaudata was sister to A. laniger (an alliance supported by morphological work). A second clade was composed of the traditional morphologically based Macroura Group: five Sminthopsis comprised a strongly supported clade that included S. crassicaudata , S. binds, S. macroura , S. douglasi , and S. virginiae . This clade of five dunnarts was a poorly supported sister to the three species of Ningaui (N. ridei , N. timealeyr, and N. yvonneae). The combined clade of five Sminthopsis and three Ningaui was positioned as poorly supported sister to a well-supported clade containing the remaining species of Sminthopsis (the 13 species comprising the Murina Group). S. ooldea was positioned as sister to a clade containing a well-supported sister pairing of S. archeri with another clade containing five species: S. murina , S. gilberti, S. leucopus , S. butleri , and S. dolichura . S. ooldea is a little-known species, named by E. Le G. Troughton in 1965 based on a type specimen collected by H. E. Green at Ooldea on the route of the Transcontinental Railway in western South Australia. Although this species was virtually unknown to biologists until the 1970s, it has since been captured regularly elsewhere in pitfall traps set during biological surveysin arid regions. Monotypic.

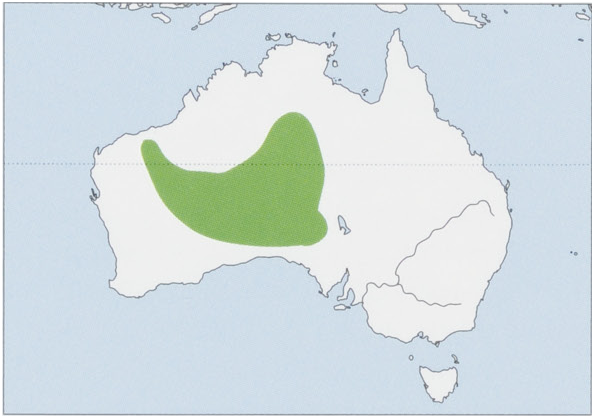

Distribution. Australia, in Western Australia, Northern Territory, and South Australia. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 6.8-5 cm (males) and 5.5-8.5 cm (females), tail 6-5— 9-5 cm (males) and 6-9 cm (females); weight 9-17 g (males) and 8-15 g (females). Fur of the Ooldea Dunnart is grayish-brown or grayish-yellow above, belly hair is white with gray at base, and overall appearance is slightly shaggy. Tail is longer than headbody length; ears are large and triangular; interdigital pads of hindfeet are not fused or are joined only at the base, with a row ofslightly enlarged granules. Terminal pads on digits are smooth. The Ooldea Dunnart is similar in general appearance to the Fat-tailed Dunnart (S. crassicaudata ), the Stripe-faced Dunnart (S. macroura ), and the Common Dunnart (S. murina ), but on average, adults weigh less and are shorter in head-body length.

Habitat. Primarily mulga ( Acacia aneura, Fabaceae ) shrublands and woodlands with a tussock grass understory. Less commonly, the Ooldea Dunnart is captured in dunes and sand plains exhibiting extensive shrublands and spinifex (7riodia spp., Poaceae ) hummock grasslands. Rarely,itis trapped in chenopod shrublands on clay soils. In one recent study at Uluru—Kata Tjuta National Park, Northern Territory, the Ooldea Dunnart was most likely to be encountered in habitats dominated by mulga rather than habitats where this plant was only a minor vegetative component. Ooldea Dunnarts may respond to thresholds in cover of mulga. Temporal variation in capture rates at the site with the highest mulga cover was low, and it was the onlysite at which the Oo-Idea Dunnart was recorded during the wet years of 2000 and 2002. These data suggest dense mulga woodland may be critical refugia for Ooldea Dunnarts in the study area.

Food and Feeding. Captive Ooldea Dunnarts fiercely attack and devour invertebrates such as grasshoppers, beetles, and spiders. Individuals in pitfall traps regularly kill and eat other small mammals and reptiles captured in the same trap. The Ooldea Dunnart may develop a fattened tail, but it is never as corpulent as in Fat-tailed Dunnarts and Stripe-faced Dunnarts.

Breeding. The Ooldea Dunnart is monestrous; young are born in spring and become independent in midsummer. Most females have eight teats; litters born in captivity typically have 7-8 young; however, wild-caught individuals usually have 5-6 young. Young detach themselves from teats at c.30 days old, at which time they have sparse gray fur and head-body length of ¢.20 mm. Eyes of young open at c¢.45 days, and at this age, offspring often cling tightly to their mother’s back. By ¢.70 days, having attained a weight of ¢.5 g and head-body length of ¢.60 mm, young are largely independent.

Activity patterns. Torpor is occasionally observed in captive Ooldea Dunnarts, butit is unknown if this is a feature ofits daily cycle (as in the Stripe-faced Dunnart) or a response to temporary food shortage. In one study, metabolic rate and water loss of Ooldea Dunnarts were measured to better understand its thermoregulatory patterns. Ooldea Dunnarts spent minimal energy and water on thermoregulation, perhaps in response to very low productivity of the hyperarid climate in central Australia.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. It is not known if young Ooldea Dunnarts remain associated with their mother after weaning or if any other social aggregations occur in the wild. Adult females frequently produce a clicking call at, or around, the time they are in estrus, which may serve to attract mates.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Oo-Idea Dunnart has a wide distribution and presumably a large overall population. It is only sparsely distributed, but like many species of Sminthopsis , it can be locally common. Populations of Ooldea Dunnarts fluctuate with rainfall. They have been recorded from a number of protected areas including Uluru-Kata Tjuta and West MacDonnell national parks in Northern Territory, Gibson Desert and Plumridge Lakes nature reserves in Western Australia, and Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara and Maralinga Tjarutja aboriginal lands in South Australia. In one study, 81 Ooldea Dunnarts were captured at 46 of 144 survey quadrants (almost 7000 trap nights) during biological surveys in Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Aboriginal Lands in the 1990s. In one recent study conducted in Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park in the south-western Northern Territory, 320 km south-west of Alice Springs, researchers captured relatively few individuals, but capture rate in pitfall traps was almost two times greater than that in Elliott traps. Capture success for Ooldea Dunnarts using pitfall traps (0-95%) was similar to the 1-2% reported elsewhere. Ooldea Dunnarts are only rarely found in sympatry with larger and potentially dominant congeners such as Fat-tailed Dunnarts and Stripe-faced Dunnarts. In surveys at Uluru, the most frequently encountered dasyurid was the Lesser Hairy-footed Dunnart (S. youngsoni ); there were 104 Lesser Hairyfooted Dunnart captures compared to 37 Ooldea Dunnart captures across the study period. Ecologists were unable to detect any obvious population response of Ooldea Dunnarts to fire; however, mulga-dominated habitats that provide the stronghold for the Ooldea Dunnart generally did not burn extensively. There was possibly an inverse relationship between capture rates of Ooldea Dunnarts and rainfall. Only one Ooldea Dunnart was captured in the wet year of 2000, and none were captured in 2002 following exceptional rain in the prior twelve months.

Bibliography. Archer (1981a), Aslin (1983), Baverstock et al. (1984), Bennison et al. (2013), Blacket, Adams et al. (2001), Blacket, Cooper et al. (2006), Burbidge, Robinson & Woinarski (2008), Foulkes (2008), Krajewski et al. (2012), Robinson et al. (2003), Tomlinson et al. (2012), Troughton (1965b).

56. Kangaroo Island Dunnart (Sminthopsis aitken), 57. Chestnut Dunnart (Sminthopsis archer), 58. Kakadu Dunnart (Sminthopsis bindi), 59. Butler's Dunnart (Sminthopsis butleri), 60. Fat-tailed Dunnart (Smunthopsis crassicaudata), 61. Little Long-tailed Dunnart (Sminthopsis dolichura), 62. Julia Creek Dunnart (Smunthopsis douglasi), 63. Gilbert's Dunnart (Sminthopsis gilbert), 64. White-tailed Dunnart (Sminthopsis granulipes), 65. Grey-bellied Dunnart (Sminthopsis griseoventer), 66. Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart (Smunthopsis hirtipes), 67. White-footed Dunnart (Sminthopsis leucopus), 68. Greater Long-tailed Dunnart (Sminthopsis longicaudata), 69. Stripe-faced Dunnart (Sminthopsis macroura), 70. Common Dunnart (Sminthopsis murina), 71. Ooldea Dunnart (Sminthopsis ooldea), 72. Sandhill Dunnart (Sminthopsis psammophila), 73. Red-cheeked Dunnart (Sminthopsis virginiae), 74. Lesser Hairy-footed Dunnart (Sminthopsis youngsoni)

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Sminthopsis ooldea

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Sminthopsis ooldea

| Troughton 1965 |

1 (by felipe, 2022-06-01 12:15:38)

2 (by ExternalLinkService, 2022-06-01 12:34:41)

3 (by tatiana, 2022-06-01 12:54:41)

4 (by tatiana, 2022-06-01 17:10:38)

5 (by ExternalLinkService, 2022-06-01 18:19:50)

6 (by ExternalLinkService, 2022-06-02 20:30:33)

7 (by tatiana, 2022-06-03 13:04:19)

8 (by ExternalLinkService, 2022-06-03 13:15:02)

9 (by ExternalLinkService, 2022-06-03 14:33:01)

10 (by plazi, 2023-11-07 04:53:24)

11 (by ExternalLinkService, 2023-11-07 06:29:34)