Sminthopsis murina (Waterhouse, 1838)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602911 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FF92-2478-FA03-F5C009C10D4A |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Sminthopsis murina |

| status |

|

Common Dunnart

Sminthopsis murina View in CoL

French: Petit Dunnart / German: Kleine SchmalfuRbeutelmaus / Spanish: Raton marsupial de cola delgada

Other common names: Common Marsupial Mouse, Mouse-sminthopsis, Slender Mouse Sminthopsis, Slender-tailed Dunnart

Taxonomy. Phascogale murina Waterhouse, 1838 , N of Hunter River , New South Wales, Australia.

Systematics of Sminthopsinae’s 28 recognized species has been the subject of considerable morphological and molecular investigation. Most notably, genetic phylogenies have failed to support monophyly of the genus Sminthopsis with respect to Antechinomys and Ningaui . There were three deeply divergent clades of Sminthopsis . In the first, S. longicaudata was sister to A. laniger (as supported by morphology). The second clade was composed of the traditional morphologically based Macroura Group: five Sminthopsis comprised a strongly supported clade that included S. crassicaudata , S. bindi , S. macroura , S. douglasi , and S. virginiae . This clade of five dunnarts was a poorly supported sister to the three species of Ningaui (N. ridei , N. timealeyi , and N. yvonneae). The combined clade of five Sminthopsis and three Ningaw: in turn was positioned as a poorly supported sister to a well-supported clade containing the remaining species of Sminthopsis species (13 species in the Murina Group). In 1965, E. Le G. Troughton included S. leucopus and S. ooldea under S. murina ; Tate considered S. leucopus to be a subspecies of S. murina ; and M. Archerlater believed S. leucopus and S. murina siblings but distinct. Archer recognized a variety of other forms under S. murina in his 1981 generic review, but he did not attempt to statistically validate subspecies in the group. In the case of S. murina, Archer considered variation to be clinal, synonymizing S. m. albipes, S. murina , and S. m. tatei with S. murina . Nevertheless, Archer used these names to qualify the form of species occurring in the vicinity. In 1984, D. J. Kitchener and colleagues redefined murina and, with the benefit of access to concurrent electrophoretic work by P. R. Baverstock and colleagues, named four new species: S. dolichura , S. gilberti, S. griseoventer , and S. aitkeni . The relationships among the group have been clarified further in recent direct DNA sequencing studies: The large dunnart clade including 13 species noted above exhibited a well-supported sister pairing of S. archeri with a clade containing five species: S. murina , S. gilberti, S. leucopus , S. butleri , and S. dolichura . S. murina was recovered with good supportas sister to S. gilberti. This clade, in turn, is evidently sister to a clade containing S. leucopus , S. butleri , and S. dolichura . Interestingly, the other two forms recognized by Kitchener in the morphological murina complex, S. griseoventer and S. aitkeni , were positioned assisters elsewhere in the 13species cluster. Taxonomic status of the two disjunct forms of S. murina (nominate murina and tater) is unfortunately unclear. In 1984, Baverstock and colleagues found little electrophoretic distinction between murina and tatei, and other researchers successfully bred these forms, producing viable offspring. In their 1984 revision, Kitchener and colleagues noted tatei could be distinguished from nominate murina by the same morphological criteria that separated other species recognized in the S. murina complex; nominate murina appeared to be divisible into two groups: one to the east and south of the Great Dividing Range and the other composed of individuals from north-eastern Queensland and Murray Darling Basin. Recent genetic work has shown that within S. murina , genetic relationships do not appear to correspond to currently recognized subspecific definitions. In most analyses, nominate murina from east of the Great Divide in New South Wales (Smiths Lakes) appears more closely related to specimens collected in northeastern Queensland (tater) than to the form murina collected from west of the Great Divide. Genetic difference between these three groups (tater, murina west of the Great Divide, and murina east of the Great Divide) is, interestingly, similar to divergences between currently recognized subspecies within the likes of S. leucopus . Thus, in addition to possessing a morphologically and genetically distinct form in north-eastern Queensland (tatei), there are evidently at least two genetically distinct groups within what is currently recognized as nominate murina . Notably, the form murina from west of the Great Divide is morphologically distinguishable from eastern and southern murina in possessing typically longer tails and having more closely spaced palatal vacuities in the skull (holes on underside of snout). Traditional subspecies are recognized here, but they may need further revision. Two subspecies recognized.

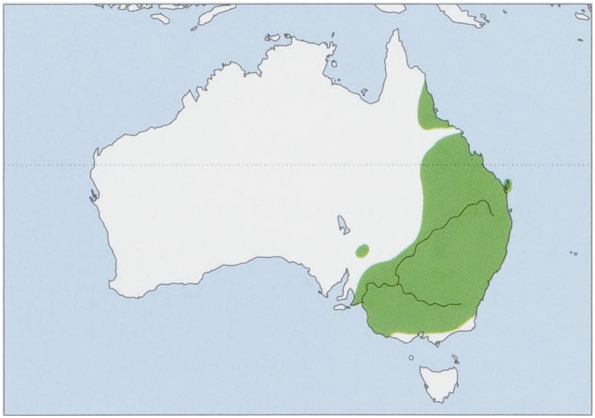

Subspecies and Distribution.

S. m. tate: Troughton, 1965 — NE Queensland.

The subspecies are probably allopatric, with neither form apparently occurring in mideastern Queensland, a known biogeographical barrier to many terrestrial vertebrates. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 7.6-10.4 cm (males) and 6.4-9.2 cm (females), tail 7.9-9 cm (males) and 6.8-9.2 cm (females); weight 16-28 g (males) and 10-22 g (females). There is sexual dimorphism for size. Fur of the Common Dunnart is mousegray above and predominantly white below. It has a slender, pointed muzzle, and large ears and eyes. The Common Dunnart is most similar to the Little Long-tailed Dunnart (S. dolichura ), Gilbert's Dunnart (S. gilberti), the Grey-bellied Dunnart (S. griseoventer ), and the Kangaroo Island Dunnart (S. aitkeni ), for which geographical location may be the best distinguishing feature; all four species occur west of the Flinders Ranges. Common Dunnarts can be distinguished from Little Long-tailed Dunnarts by their shorter tail and brownish dorsal fur, Gilbert's Dunnarts by shorter hindfeet and ears, Grey-bellied Dunnarts by white rather than gray belly fur, Kangaroo Island Dunnarts in not having dark and sooty back hair, and Fat-tailed Dunnarts (S. crassicaudata ) by nonfused and hairless interdigital pads on hindfeet. Common Dunnarts differ from the White-footed Dunnart (S. leucopus ) by lacking striations on their interdigital pads and having small hallucal pads on feet and from the Stripe-faced Dunnart (S. macroura ) by absence of any head-stripe (although dark patch may be present). Tail length of the Common Dunnart is variable, but it is about equal to its head—body length and never fat, as sometimes is the case in the Stripe-faced Dunnart, the Fat-tailed Dunnart, and the Ooldea Dunnart (S. ooldea ).

Habitat. Most commonly in woodland, open forest, and heathland but also transitional habitat close to rainforest. Common Dunnarts are replaced by the White-footed Dunnart in similar habitats in coastal regions of Victoria, and they are absent from highelevation closed forests in northern Queensland.

Food and Feeding. Common Dunnarts are insectivorous. Although they feed on beetles, cockroaches, cricket larvae, and spiders, they also readily eat common bait mixture of peanut butter and oats, as do many species of otherwise insectivorous dasyurids. In one study conducted in the Myall Lakes area of New South Wales, the Common Dunnart exhibited dietary preferences similar to other small dasyurids that have been studied; it was opportunistic, feeding on a wide variety of arthropod prey available to it. Nevertheless, they ingested significantly more Scarabaeidae, Blattodea , Coleoptera, Lepidoptera , and larvae and fewer Formicidae, Orthoptera, and Isopoda than were available in pitfall traps during spring and summer. In autumn and winter, Common Dunnarts also ate significantly more Araneida and fewer Diptera . Lepidoptera, Orthoptera, and various larvae were also eaten but in similar proportions to which they occurred naturally.

Breeding. At the onset of breeding, male Common Dunnarts become increasingly aggressive toward each other; indeed, they can be seriously wounded in combat. Vocalization by females attracts males. Estrous cycle is 24 days; two litters can be born during the breeding season in August-March. Features of high reproductive rate of the Common Dunnart that promote population increase following colonization of burned areas include short gestation of 12-5 days, reduced parental care, rapid development of young weaned at ¢.65 days, and litters of up to ten young on the 8-10 teats in females’ pouches. After c.150 days old, individuals can be considered adult.

Activity patterns. The Common Dunnart is nocturnal and rests during the day in a cup-shaped nest of dried grass and leaves built in a fallen hollow log, a clump ofgrass, a grass tree (Xanthorrhoea, Xanthorrhoeaceae ), or perhaps beneath fallen tree bark or in ground cover. In one telemetry study examining patterns of movement, activity, and torporin free-living Common Dunnarts over one autumn-winter period in warmtemperate habitat, individuals rested during the day in burrows and hollow logs. They maintained several daytime refuges, foraging across several hectares each night. They preferred agamid (dragon lizard) burrows where daily temperatures of 10-3-15-8°C were maintained when ambient surface temperatures were 3-5-24-6°C. Torpor was used in twelve of 13 complete resting periods recorded. Common Dunnarts used both long (more than six hours) and short (less than four hours) torpor bouts, where their minimum skin temperature was 17-2-26-7°C. Torpor usually occurred in the morning, although bouts were also recorded in some afternoons. Arousal rates from torpor were variable and achieved by endogenous and passive means. Normal-temperature resting periods tended to be short (mostly less than three hours). Variable physiological responses observed in Common Dunnarts appear to follow a facultative pattern. Along with long activity periods and their use of refuge sites, their physiology may be linked to variable invertebrate activity during cooler months.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Common Dunnart appears adapted to a mid-successional complex of vegetation; it evidently benefits from periodic burning of its habitat. Local distribution is usually patchy, but in areas burned in the previous 2-4 years, densities of up to 6 ind/ha have been recorded. The Brown Antechinus ( Antechinus stuartit) and Common Dunnart are often found in similar habitats but with clear spatial and ecological separation. In one study, these species were subjected to experimental encounters in outdoor enclosures. The Brown Antechinus dominated strongly competitive interactions; indeed, a Brown Antechinus killed a Common Dunnart during one agonistic encounter. Another study reported habitat fidelity in a dense population of subadult Common Dunnarts in coastal wet heath environment in New South Wales. Individuals were captured repeatedly in the first 16 months following a wildfire (30 subadults, 23 males, and seven females were trapped 154 times). Density peaked c.10 months after the fire at an impressive 3-7 ind/ha. Interestingly, more captures were made in areas of high soil moisture in the first six months following the fire. Captures subsequently decreased in such areas, but they increased where soil moisture had previously been lower and vegetation had been growing more slowly. In succeeding months, regenerating vegetation became increasingly dense, whereupon captures of Common Dunnart ultimately declined to zero. The study indicated that Common Dunnarts might have a narrow range of habitat requirements that is met for only brief periods during secondary succession of vegetation. Nomadic movements are probably necessary for Common Dunnarts to find optimal habitat conditions; thus, there are often low captures in trapping studies. This may well be common in other species of Sminthopsis . In another study, competitive behavior of three species of dasyurids (Dusky Antechinus , Antechinus swainsonii ; Brown Antechinus ; and Common Dunnart) was assessed in enclosures and small encounter cages, looking at interactions of pairs of individuals. Encounters were particularly prevalent within Dusky Antechinus and Brown Antechinus , indicating that they were more social than the relatively solitary Common Dunnart. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the smaller competitor, the Common Dunnart, avoided the larger Brown Antechinus .

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Common Dunnart has a wide distribution and presumably a large overall population, and it is unlikely to be declining at nearly the rate required to qualify for listing in a threatened IUCN category. Itis common in some parts ofits distribution but rare elsewhere (e.g. in the south). In some parts of its distribution, such as in Victoria, it may be undergoing steeper population declines. From 1989 to early 1992, Common Dunnarts appeared to be rare along the central New South Wales coast, despite previous captures in reasonable numbers; however, by 1994, they were again abundant. In general, there appear to be no major threats to the Common Dunnart, although predation by domestic and feral cats and Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) and habitat degradation may be resulting in some localized declines. Common Dunnarts are present in a number of protected areas.

Bibliography. Archer (1981a), Baverstock et al. (1984), Blacket, Adams et al. (2001), Blacket, Cooper et al. (2006), Dickman, Burnett & McKenzie (2008), Fox (2008), Fox & Archer (1984), Fox & Whitford (1982), Kitchener et al. (1984), Krajewski et al. (2012), Maxwell et al. (1996), Monamy & Fox (2005), Paull (2013), Righetti et al. (2000), Troughton (1965b).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Sminthopsis murina

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Phascogale murina

| Waterhouse 1838 |