Sminthopsis leucopus (Gray, 1842)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602905 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FF90-247E-FA07-F9D90CF00CEB |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Sminthopsis leucopus |

| status |

|

White-footed Dunnart

Sminthopsis leucopus View in CoL

French: Dunnart a pattes blanches / German: Rippsohlen-Schmalful 3beutelmaus / Spanish: Raton marsupial de pies blancos

Other common names: \ White-footed Marsupial Mouse

Taxonomy. Phascogale leucopus Gray, 1842 ,

Tasmania, Australia.

Phylogenetic relationships among the 28 species in the clade Sminthopsinae have been both morphologically and genetcally scrutinized in several independent studies. Most recently, a genetic phylogeny did not support monophyly of the genus Sminthopsis View in CoL with respect to Antechinomys View in CoL and Ningauwi. Three deeply divergent clades of Sminthopsis View in CoL were resolved. In the first, S. longicaudata View in CoL was sister to A. laniger View in CoL (an alliance also obtained from previous morphological analyses where there was good reason to include Antechinomys View in CoL within Sminthopsis View in CoL and also to link it with S. longicaudata View in CoL ). The second clade was composed of the traditional morphologically based Macroura View in CoL Group: five Sminthopsis View in CoL comprised a strongly supported clade that included S. crassicaudata, S. bindi View in CoL , S. macroura View in CoL , S. douglas, and S. virginiae View in CoL . This clade of five dunnarts was a poorly supported sister to the three species of Ningaui View in CoL . The combined clade of five Sminthopsis View in CoL and three Ningawi was positioned as a poorly supported sister to a well-supported clade containing the remaining species of Sminthopsis View in CoL (13 species in the Murina Group). This large dunnart clade contained, in part, a well-supported sister pairing of S. archer: with a clade containing five species: S. murina View in CoL , S. gilberti, S. leucopus , S. butler , and S. dolichura View in CoL . Genetically, S. leucopus was positioned in a well-supported clade also containing S. butler : and S. dolichura View in CoL . The north-eastern Queensland population of S. leucopus was first discovered in 1966 when an adult female was collected by P. Johnson in rainforest adjacent to Paluma Dam. In 1982, S. Van Dyck and H. Plowman collected another specimen farther north in the Wet Tropics near Ravenshoe. Van Dyck formally reported these specimens in a 1985 research paper after M. Archer’s (1981) comprehensive review of the genus. Although subsequent allozyme genetic work confirmed close affinity between these animals and southern S. leucopus , direct DNA sequencing of mtDNA and systematic analysis are still required to confirm status and relationships of S. leucopus in northern Queensland, where it is isolated and separated by an astonishing 2100 km from its nearest conspecifics in the south. In a recent genetic study, a specimen of S. leucopus from Queensland was found to be as divergent from each of the south-eastern Australian S. leucopus subspecies as they are from each other, suggesting that this northern population of S. leucopus may also warrant recognition as a distinct taxon. Yet, the Queensland population is currently only known at five locations, from three whole museum specimens and some skeletal material from owl roosts. This northern form of S. leucopus has only rarely been encountered alive in the last two decades; more vouchers to permit more detailed combined genetic and morphometric work are needed. Two subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

S. l. leucopus Gray, 1842 — Tasmania.

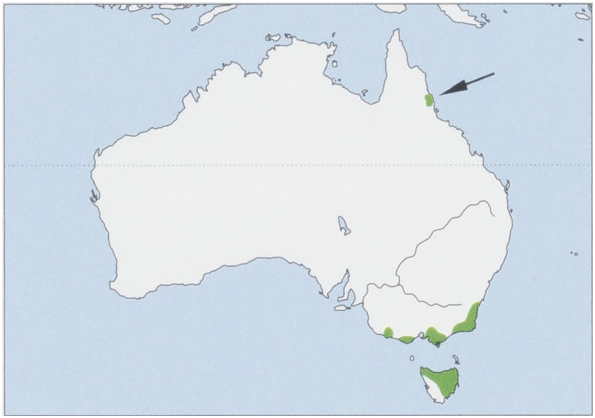

S. I ferruginifrons Gould, 1854 — SW New South Wales, S Victoria, and NE Queensland. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 6.7-9.8 cm, tail 6.7-8.2 cm; weight 16-32 g for New South Wales and Victoria populations; head—body 10-6 cm (males) and 8.8-10.1 cm (females), tail 10 cm (males) and 8.7-9.6 cm (females); weight 25 g or more (females) for north Queensland populations; head-body 9.8-11.2 cm (males) and 9.5-11.7 cm (females), tail 7.3-10 cm (males) and 7.9-5 cm (females); weight 32 g (males) and 24 ¢ (females) for Tasmanian populations. There is sexual dimorphism for size. Fur on back and face of the White-footed Dunnartis pale brownish-yellow with black guard hairs, giving it a brown-gray pattern; belly fur is off-white, gradually darkening along flanks. Eyes are large, dark, and protruding; large, thin ears can be laid back against head; and there is brown skin on top of muzzle. Feet appear pink with a covering of fine, white hair. North Queensland specimens have gray fur on cheeks. The Whitefooted Dunnartis similar to the Common Dunnart (S. murina ), but it typically has striations on its interdigital footpads and is slightly heavier. The two species can co-occur and are hard to distinguish based on external characters alone.

Habitat. Mature and regenerating notophyll vine forest at elevations of at least 750 m in north-eastern Queensland; heath woodland and forest, coastal scrub, and coastal dune grassland in New South Wales and Victoria; and sclerophyll forest, heath, and rainforest at elevations up to 810 m in Tasmania. The White-footed Dunnart lives in early to mid-successional stages, postfire or postlogging in coastal areas. One field study in Mumbulla State Forest, south-eastern New South Wales, found that within three years of forest growth after logging and fire, White-footed Dunnarts had deserted the open, highly disturbed sites they had initially selected. In the Otways in southern Victoria, White-footed Dunnarts were found in regrowth 4-16 years postfire, with peak numbers 4-9 years postfire; this suggested a preference for mid-successional habitats.

Food and Feeding. White-footed Dunnarts prey on a wide variety of invertebrates, up to 1-8 cm in length. They will capture skinks weighing up to 15 g. A captive male and female White-footed Dunnart rapidly caught and consumed cockroaches, moths, and beetles; on one occasion, they vigorously attacked and ate a large huntsman spider ( Sparassidae ) by biting off and consuming one leg at a time and then eating its legless body at their leisure.

Breeding. In New South Wales and Victoria, mating of White-footed Dunnarts occurs in late July and August. Laboratory studies of White-footed Dunnarts have found that females can breed more than once in a season; this has yet to be observed in the wild. Females typically have ten teats that begin to enlarge in late July, at which time pouch skin also swells and reddens; pouch hairs become white and shiny. From mid-August to mid-September, up to ten young are born, with a crown-rump length of ¢.3 mm; their length doubles within a week. At c.8 weeks, young detach from teats and are suckled in a nest for c.1 month. One captive study indicated that females have ten nipples. Three female White-footed Dunnarts trapped in August had pouch development characteristic of pregnancy; one of these and two other individuals were carrying pouch young when they were trapped in September—October; none of the females trapped in March,June,July, or November showed pouch development, although one captured in March had elongated nipples, characteristic of having recently suckled young. One female White-footed Dunnart was captured in mid-October with eight pouch young estimated to be 3—4 weeks old. These young were weaned in late November and reached sexual maturity at c.11 months old in July-August.

Activity patterns. The White-footed Dunnart is terrestrial and nocturnal, with one study recording highest activity in the early evening.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. In a study at Mumbulla State Forest, juvenile White-footed Dunnarts were found during searches for reptiles along disturbed road edges; they made simple nests of a few leaves and blades of grass under strips of bark or small rotting logs. A radio-tracking study in the Otway Ranges found that White-footed Dunnarts nested in tree hollows previously occupied by Agile Antechinuses ( Antechinus agilis ) and Eastern Pygmy Possums (Cercartetus nanus) and in ground burrows; some individuals were located in heath, but no nest structures were apparent. There was no difference in movements between males and females or between seasons; home ranges of males and females overlapped and were estimated to be c.1 ha. The largest recorded movement was 205 m made by a male. This result was similar to the observations in the trapping study in Mumbulla, except that in Mumbulla, males fell into two groups: “resident” males with range lengths of 105 m and “explorer” males with the greatest movement of more than 1 km in 24 hours.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. The Whitefooted Dunnart is thought to number fewer than 10,000 mature individuals, and no subpopulation is thought to number more than 1000 individuals. Subpopulations are also known to undergo extreme fluctuations in numbers. The White-footed Dunnart is infrequently recorded, despite intensive survey work; it may well have a patchy distribution. There are estimated to be fewer than 1000 individuals in New South Wales, 2000 individuals in Victoria, and perhaps fewer than 5000 individuals in Tasmania. Only a few museum specimens represent the Queensland population of the White-footed Dunnarts, and the population size and other aspects ofits ecology are unknown. The White-footed Dunnart is an early mixed-successional species, and it has not been recorded from regrowth forest; thus, inappropriate fire regimes may result in declines. Fortunately, it occurs in a number of protected areas. The Queensland population falls within the Wet Tropics World Heritage Area. Populations in New South Wales, Victoria, and Tasmania should be monitored, particularly in areas subject to disturbances that promote dense regrowth of vegetation.

Bibliography. Archer (1981a), Baverstock et al. (1984), Blacket, Adams et al. (2001), Blacket, Cooper et al. (2006), Laidlaw et al. (1996), Lunney (2008), Lunney & Ashby (1987), Lunney & Leary (1989), Lunney, Menkhorst & Burnett (2008), Lunney, O'Connell et al. (1989), Maxwell et al. (1996), Thomas (1888b), Van Dyck (1985), Wilson & Aberton (2006), Woolley & Ahern (1983), Woolley & Gilfillan (1990).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Sminthopsis leucopus

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

bindi

| Van Dyck, Woinarski & Press 1994 |

dolichura

| Kitchener, Stoddart & Henry 1984 |

dolichura

| Kitchener, Stoddart & Henry 1984 |

Sminthopsinae

| Archer 1982 |

butler

| : Archer 1979 |

butler

| : Archer 1979 |

Ningaui

| Archer 1975 |

Sminthopsis

| Thomas 1887 |

Sminthopsis

| Thomas 1887 |

Sminthopsis

| Thomas 1887 |

Sminthopsis

| Thomas 1887 |

Sminthopsis

| Thomas 1887 |

Sminthopsis

| Thomas 1887 |

Antechinomys

| Krefft 1867 |

Antechinomys

| Krefft 1867 |

Phascogale leucopus

| Gray 1842 |

leucopus

| Gray 1842 |

leucopus

| Gray 1842 |

leucopus

| Gray 1842 |

leucopus

| Gray 1842 |

leucopus

| Gray 1842 |

leucopus

| Gray 1842 |

leucopus

| Gray 1842 |

leucopus

| Gray 1842 |

leucopus

| Gray 1842 |