Sminthopsis hirtipes, Thomas, 1898, Thomas, 1898

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602903 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FF90-247D-FF0B-FD3B09C50480 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Sminthopsis hirtipes |

| status |

|

Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart

SmInthopsis hirtipes View in CoL

French: Dunnart a pieds velus / German: Polster-SchmalfulRbeutelmaus / Spanish: Raton marsupial de pies peludos

Other common names: Fringe-footed Sminthopsis, Hairy-footed Pouched Mouse

Taxonomy. Sminthopsis hirtipes Thomas, 1898 View in CoL ,

Charlotte Waters , Northern Territory, Australia.

Phylogenetic relationships among the 28 species within the Sminthopsinae have been the subject of much morphological and molecular scrutiny. Interestingly, a recent genetic phylogeny (several mtDNA and nDNA genes) failed to support monophyly of the genus Sminthopsis View in CoL with respect to Antechinomys View in CoL and Ningauwi. There were three deeply divergent clades of Sminthopsis View in CoL . In the first, S. longicaudata View in CoL was sister to A. laniger View in CoL . In the second, there was the traditional suite comprising the morphologically based Macroura View in CoL Group: five Sminthopsis View in CoL formed a strongly supported clade that included S. crassicaudata, S. bindi View in CoL , S. macroura View in CoL , S. douglasi View in CoL , and S. virginiae View in CoL . This clade of five dunnarts was a poorly supported sister to the three species of Ningaui View in CoL (N. ride , N. timealeyi View in CoL , and N. yvonneae). The combined clade of five Sminthopsis View in CoL and three Ningawi was positioned as a poorly supported sister to a well-supported clade containing the remaining species of Sminthopsis View in CoL (13 species in the Murina Group). This large dunnart clade contained a sister pairing of S. hirtipes View in CoL with S. youngsoni View in CoL . These two taxa, in turn, were positioned as sister to S. psammophila View in CoL , but neither of these clades was strongly supported. S. hirtipes View in CoL wasfirst described by O. Thomas in 1898 from a specimen collected near Charlotte Waters, Northern Territory. M. Archer recognized the species as distinctive in external characters alone. When Thomas described the stalker: form of S. hutipes in 1906, he believed it was intermediate in some respects between S. hirtipes View in CoL and S. larapinta (today, S. macroura View in CoL ). Nevertheless, Archer, in his impressive 1981 review of Smanthopsis, placed stalkeri within macroura View in CoL because terminal pads of toes in types of stalkeri are not granular, which was a clear and characteristic feature of S. hurtipes. Monotypic.

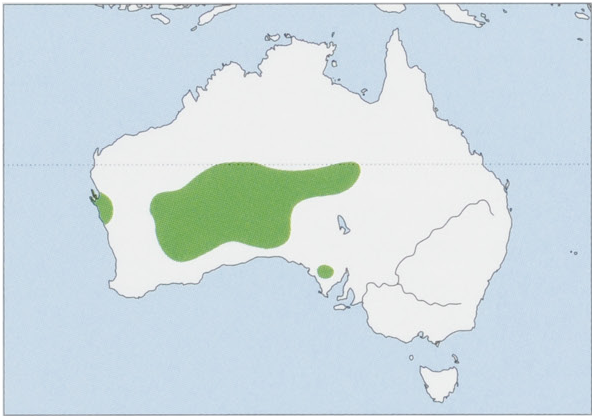

Distribution. Australia, in arid and semi-arid habitats from Western Australia to SW Queensland; there is an outlying population in the Eyre Peninsula, S South Australia. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 7.2-8.3 cm, tail 7.2-10.1 cm; weight 13-19-5 g. Fur of the Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart is brownish to pale yellowish-brown above, with black-tipped hairs giving peppered appearance; fur is white below. Basal half oftail is typically slightly swollen. The Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart can be distinguished from other species of Sminthopsis , including the Lesser Hairy-footed Dunnart (S. youngsoni ), by long (16-19 mm), broad feet, covered with fine, silvery hairs; hairs are short on foot pads and long elsewhere, forming a fringe around the sole.

Habitat. Variety of plant communities associated with reddish sand plains and sand dunes, including open low woodlands of marble gum ( Eucalyptus gongylocarpa, Myrtaceae ), E. youngiana, or desert oak ( Allocasuarina decaisneana , Casuarinaceae ) and shrublands of Acacia (Fabaceae) , Thryptomene (Myrtaceae) , or Grevillea (Proteaceae) over hummock grasslands. In the south-western part of its distribution, the Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart has been found in Callitris (Cupressaceae) woodland, shrub mallee, heath, and hummock grassland plant communities on plains or dunes of red to yellow sands. Near the coast at Shark Bay and Kalbarri, Western Australia, Greater Hairy-footed Dunnarts have been collected in shrublands and low open woodlands of Banksia (Proteaceae) and Grevillea on gray-yellow sand plains. In one study in central Australia, near Uluru, spinifex (7riodia spp., Poaceae ) cover was a predictor of occurrence of the Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart, similar to a variety of dasyurids and rodents in arid regions of Australia. Rainfall is irregular throughout much of the distribution of the Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart.

Food and Feeding. The diet of the Greater Hairyfooted Dunnart includes insects, spiders, and small lizards. Individuals have been found during the day in abandoned bull-ant nests and once in a deep burrow (perhaps excavated by hopping-mice, Notomys sp. ). Base of the Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart’s tail fattens during good seasons; fat from tail can then be reabsorbed as energy in lean times—often the case for species of Sminthopsis and some other dry-habitat dasyurids and rodents.

Breeding. In the Great Victoria Desert and semi-arid Eastern Goldfields of Western Australia, births of Greater Hairy-footed Dunnarts are strongly seasonal, occurring in spring and summer. Females with pouch young have been recorded as early as October and lactating females as late as April. Greater Hairy-footed Dunnarts can live for at least three years in the wild.

Activity patterns. There is no specific information available for this species, but Greater Hairy-footed Dunnarts are most likely nocturnal.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. In central Australia, Greater Hairyfooted Dunnarts appear to be most abundant in hummock grassland burned no more than four years previously. At a southern desert site, juveniles were found to disperse across recent fire scars in late summer, but they did not establish home ranges there. In one detailed study in1987-1989 near Bulgalbin Hill in the Western Goldfields of Western Australia, 65 Greater Hairy-footed Dunnarts were caught; excluding recaptures within grids, mean distance moved was 1 km. Importantly, distances moved as much as doubled in wet conditions. During the study, researchers recorded an extension of range of the Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart into the eastern Simpson Desert in 1992; this appeared to be due to the long-range movements of individuals following unusually heavy rainfall. Another study was conducted in central Australia, near Uluru. Thirty-five Greater Hairy-footed Dunnarts were caught, and number of captures varied by seasons, with the majority caught in August.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCNRed List. The Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart has a wide distribution, presumably has a large overall population, occurs in a number of protected areas, and does not face any major conservation threats. It is most abundant during good rainfall. The presumed rarity of the Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart has been the result of inappropriate collecting techniques in the past; where present,itis readily captured in pitfall traps. Greater Hairy-footed Dunnarts are regularly caught on Peron Peninsula but in lower numbers than Little LLongtailed Dunnarts (S. dolichura ). Broad-scale, altered fire regimes and predation by Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) and domestic and feral cats are threats to the Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart in local areas. The Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart has been recorded from a number of protected areas, including Kalbarri National Park, Francois Peron National Park, Wanjarri Nature Reserve, Neale Junction Nature Reserve, Queen Victoria Spring Nature Reserve (all in Western Australia), Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park (Northern Territory), and the “Unnamed” Conservation Park (South Australia). There is a historical record from Bernier (or Dorre) Island, but the Greater Hairy-footed Dunnart is evidently no longer present there.

Bibliography. Archer (1981a), Baverstock et al. (1984), Blacket, Adams et al. (2001), Blacket, Cooper et al. (2006), Dickman, Downey & Predavec (1993), Dickman, Predavec & Downey (1995), Krajewski et al. (2012), Masters (1993), McKenzie & Dickman (2008a), McKenzie et al. (2000), Pearson & McKenzie (2008), Thomas (1888b, 1898c, 1906).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Sminthopsis hirtipes

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

bindi

| Van Dyck, Woinarski & Press 1994 |

Sminthopsinae

| Archer 1982 |

youngsoni

| McKenzie & Archer 1982 |

douglasi

| Archer 1979 |

Ningaui

| Archer 1975 |

ride

| : Archer 1975 |

N. timealeyi

| Archer 1975 |

Sminthopsis hirtipes

| Thomas 1898 |

S. hirtipes

| Thomas 1898 |

S. hirtipes

| Thomas 1898 |

S. hirtipes

| Thomas 1898 |

psammophila

| Spencer 1895 |

Sminthopsis

| Thomas 1887 |

Sminthopsis

| Thomas 1887 |

Sminthopsis

| Thomas 1887 |

Sminthopsis

| Thomas 1887 |

Antechinomys

| Krefft 1867 |