Phascogale calura, Gould, 1844

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602833 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FF8E-246C-FA04-FD6C0DE609E1 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Phascogale calura |

| status |

|

44. View On

Red-tailed Phascogale

French: Petit Phascogale / German: Kleine Pinselschwanzbeutelmaus / Spanish: Fascogalo de cola roja

Other common names: Red-tailed \ Wambenger

Taxonomy. Phascogale calura Gould, 1844 View in CoL ,

Williams River , Military Station , Western Australia, Australia.

The type specimen of P. calura was collected by J. Gilbert at the “Military Station on the Williams River,” 150 km south-east of Perth (Western Australia’s capital) in 1843, the early years of European settlement. J. Gould formally named the species a year later. At the time of capture, Gilbert commented “I was indebted to a domestic cat who had captured it in the night. The soldiers informed me that they had often met with it in the storeroom of the Station, but they could give me no other information respecting it, except that specimens with much larger or bushier tails were sometimes seen.” Subsequent surveys extended the species’ distribution to the junction of the Murray and Darling rivers in eastern Australia by the mid-19" century, to central Australia in the late-19"™ century, and to the Canning Stock Route in Western Australia in 1931. A live specimen was also apparently taken around Adelaide at some time before 1888. Nevertheless, for all localities other than south-western Western Australia, these were the first and last records for the species. In 2001, measurements of genetic differ entiation among P. calura , P. tapoatafa , and P. pirata (then recognized as the subspecies Pt. pirata) were estimated using mtDNA (cytochrome-b gene); 16% sequence divergence separated P. caluraand P. tapoatafa , which supported clear morphological distinctions between the two species. P. caluraand P. pirata averaged 14-6% genetic divergence, which is also corroborated by their clear morphological distinction. Monotypic.

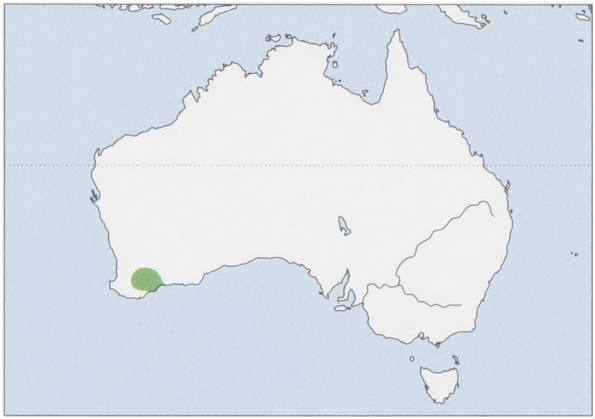

Distribution. SW Australia, now entirely confined to the Southern wheat belt region in Western Australia. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 10-5-12:2 cm (males) and 9.3-10.5 cm (females), tail 13.4-14.5 cm (males) and 11.9-14.4 cm (females); weight 39-68 g (males) and 38-48 ¢ (females). The Red-tailed Phascogale is ashy gray above and cream to white below; there is a blackish patch in front of eye. Ears and upper proximal part oftail are distinctive reddish brown; distal half oftail has a brush of long black hairs.

Habitat. A variety of habitats with greater canopy density and greater abundance of hollows than unoccupied sites. Red-tailed Phascogales are found in isolated patches of forest that receive 300-600 mm of rain/year. They prefer habitats that are generally denser and taller climax vegetation within wandoo ( Eucalyptus wandoo , Myrtaceae ) and rock sheoak ( Allocasuarina huegeliana , Casuarinaceae ); hollows in wandoo provide nesting sites. One study found that the Red-tailed Phascogale occurs mostly in woodland habitat with old-growth hollow-producing eucalypts, primarily wandoo or york gum (E. loxophleba). Records from the periphery of its current distribution appear to represent a broader variety of habitats, including shrublands, mosaics of woodland, and scrub-heath. Red-tailed Phascogales occupy areas of remnant vegetation of varying sizes from very small to very large, many on privately owned agricultural land. Large connected areas, such as riverine corridors and stands of upland remnant vegetation, appear important to long-term persistence of the Red-tailed Phascogale; however, sites isolated by increasing distance from other occupied sites tended to be unoccupied by the Red-tailed Phascogale.

Food and Feeding. Like its congeners, the Red-tailed Phascogale is arboreal. It can leap up to 2 m, covering considerable distances while foraging in the forest canopy. Red-tailed Phascogales often feed on the ground and are opportunists, taking a wide variety of insects and spiders (preferring prey less than 1 cm in length); they will also eat small birds and mammals (particularly the House Mouse, Mus musculus ). Prey satisfies water requirements. One study examined feces from Red-tailed Phascogales that had been translocated to the Alice Springs Desert Park; they were primarily insectivorous, with 92:6% of all feces containing arthropods. They also consumed birds (51:6% of feces), small mammals (33-:3%), plant material (27-4%), and occasionally reptiles; birds were a large proportion of the diet in spring.

Breeding. Female Red-tailed Phascogales show an increase in weight prior to estrus, and mating occurs during a three-week period in July. Captive copulations haves lasted up to six hours. Individual females may be receptive to males for at least five days, and births may be tightly synchronized or spread over a couple of weeks. Females are able to store viable sperm for at least four days prior to ovulation; gestation is 28-30 days. Females ovulate c.16 eggs, with up to 13 young observed at birth, despite availability of only eight teats. At least two males can sire young within a single litter. Unlike males, which all die synchronously at the conclusion of breeding, female Red-tailed Phascogales are capable of surviving and reproducing in a second or even third season. At birth, young weigh c.15 mg and are c¢.5 mm long. Fur on young begins to appear at c.34 days, and young first detach from teats while in a nest at c¢.45 days. Weaning of young occurs at ¢.90 days when they weigh c.20 g. In the wild, males live for only 11-5 months (similar to male Antechinus , the sister genus). Captive males can survive for up to five years. A recent study reported successful captive breeding in four-year-old female Red-tailed Phascogale; females can survive until at least five years of age in captivity. These findings have implications for captive breeding programs, providing evidence that older females can be successfully bred. Males are reproductively senescent after their first breeding season. Prior to mating, male germ cells needed for production of sperm are depleted, and sperm production ceases. Sperm stored in the epididymis during the mating period thus sires the next generation.

Activity patterns. Red-tailed Phascogales are mainly nocturnal, but they have been seen emerging during the day to investigate potential food sources.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Home ranges of male Red-tailed Phascogales increase about tenfold during the mating period. Home ranges of females remain at c.8 ha.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Near Threatened on The IUCN Red List. Listed as endangered in Australia. There are probably fewer than 10,000 mature Red-tailed Phascogales in the wild, and the overall population may be decreasing. Rate of decrease is likely less than 10% over ten years, so it is close to qualifying as Vulnerable under criterion C of the IUCN. Populations of Red-tailed Phascogales apparently fluctuate with rainfall. There are no apparent current population declines, but there were large declines historically. Survival of Red-tailed Phascogales in Western Australia may be related to presence of Gastrolobium and Oxylobium , legume-like plants that produce monosodium fluoracetate (‘1080’), a chemical that can be lethal to introduced species. Native species have evolved a tolerance to the fluoroacetate; their bodies can contain enough of it to poison introduced carnivores, such as the Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes), that pose threats to their survival. Too frequent burning of forests also negatively affects survival of the Red-tailed Phascogale by destroying nesting hollows and dense, protective foliage. Suitable habitat for the Red-tailed Phascogale appears widespread, but it is under threat over the longer term. Increasing dryland salinity in lowland areas, loss of dense stands of rock sheoak in upland areas, and continuing loss of corridors of vegetation along roadsides due to road widening contribute to loss of habitat and habitat connectivity. The Red-tailed Phascogale now occupies less than 1% ofits former distribution. Today, it occurs in parts of the Avon Wheatbelt, Jarrah Forest, Mallee, and Esperance Plains bioregions. Red-tailed Phascogales persist only in areas that have been extensively cleared for agriculture and where remaining bush land is highly fragmented. It does not appear to extend into unfragmented habitat in the Jarrah Forest to the west or Mallee region to the east. Predation by domestic and feral cats and red fox also reduce numbers of Red-tailed Phascogale. Taken together, these factors, particularly fragmentation and lack of suitable nesting hollows, suggest that the long-term persistence of Red-tailed Phascogales in areas beyond the wandoo belt is far from assured. One study on a translocated population found that Red-tailed Phascogales are able to exploit various prey types and therefore are likely candidates to survive a “hard” (without acclimation prior to release) translocation into the wild, provided the site chosen had adequate food supply.

Bibliography. Bradley (1997), Bradley et al. (2008), Foster & Taggart (2008), Foster et al. (2006), Friend (2008b), Gould (1844, 1863), Kitchener (1981), Short & Hide (2012), Short et al. (2011), Spencer et al. (2001), Stannard, Borthwick et al. (2013), Stannard, Caton & Old (2010).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Phascogale calura

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Phascogale calura

| Gould 1844 |