Melanocanthon Halffter, 1958

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10270977 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:FA7D5D5E-CEB8-48ED-A442-74C315FCF5E4 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA615F14-FFA3-FFD6-FF1C-F9C6FA084EF5 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Melanocanthon Halffter, 1958 |

| status |

|

Genus Melanocanthon Halffter, 1958 View in CoL

Melanocanthon Halffter 1958: 210 View in CoL .

Type species. Canthon bispinatus Robinson, 1941 View in CoL , by original designation.

Diagnosis. (presumed apomorphic features, in the context of the autochthonous US fauna of deltochilines, are italicized): • Small (length 5–10 mm), usually dull black, ball-rolling dung beetles (“tumblebugs”) ( Fig. 1–2 View Figures 1–8 ). • Clypeal margin ( Fig. 12 View Figures 9–14 ) quadridentate, middle teeth large, acute apically, lateral teeth widely, obtusely angulate; clypeal teeth, combined with small, anterior prominences of the paraocular areas, produce a weakly sexdentate anterior head margin. • Clypeal process spiniform ( Fig. 4–5 View Figures 1–8 ), abraded to triangular tooth in worn specimens ( Fig 6 View Figures 1–8 ). • Anterior angle of paraocular area weakly produced, angulate ( Fig. 12 View Figures 9–14 ); paraocular notch obsolete. • Frontoclypeal suture very fine, sometimes nearly effaced. • Posterior margin of head completely, very finely margined. • Labiogular fimbria ( Fig. 8 View Figures 1–8 , arrow) narrowly V-shaped, apex extending posteriorly sometimes beyond middle of gula. • Lateral pronotal angles widely obtuse such that pronotum (viewed from above) appears “broad shouldered” ( Fig. 12 View Figures 9–14 ); lateral pronotal fossae obsolete, sometimes represented by a weak bump. • Anterolateral portion of pronotal margin ( viewed dorsally, Fig. 12 View Figures 9–14 ) almost straight, and ( viewed laterally, Fig. 7 View Figures 1–8 ) strongly bowed upwards to accommodate front leg; anterior end of bow followed by single coarse tubercle and row of smaller bumps reaching anterior angle. • Pronotum (viewed laterally) raised above level of elytra (“humped”) and (viewed dorsally) slightly impressed along midline from posterior angle to near middle of disk. • Hypomeral carina absent. • Elytral profile ( viewed dorsally, Fig. 11 View Figures 9–14 ) more-or-less evenly curved from umbones to pygidium such that body appears gradually narrowed posteriorly; dorsal silhouette more or less acorn-shaped. • Eight elytral striae; striae very weak, superficial, and often difficult to discern, lateral striae (5–8) often mostly effaced; interstriae flat • Outer margin of protibia ( Fig. 3 View Figures 1–8 ) strongly tridentate, serrate basally and between large teeth; inner margin abruptly offset at level of third (basal) lateral tooth; inner apical angle sometimes produced as conical tubercle. • Protibial spur sexually dimorphic: apex acute in female, bifurcate in male ( Fig. 3 View Figures 1–8 ). • Ventral surfaces of femora completely, evenly punctured, punctures well defined, fairly dense. • Metafemur lacking carina along anterior margin. • Metatibia with two apical spurs ( Fig. 26 View Figures 20–26 , 39 View Figures 34–42 , 55 View Figures 51–58 ) • Pygidium ( Fig. 10 View Figures 9–14 ) completely margined, evenly covered with distinct granules on shagreen background; base impressed, sometimes only weakly so, on each side of raised midline; apex always strongly convex. • Parameres ( Fig. 23 View Figures 20–26 , 31–32 View Figures 27–33 , 56–58 View Figures 51–58 ) compressed laterally, apex (viewed laterally) truncate, lower apical lobes (viewed caudally) rounded knobs or flattened tabs. • Dorsum (including pygidium) often with distinct, raised granules on very fine shagreen background (50×) intermingled with minute, scattered, setose punctures especially on head and pronotum (Note: Setae readily perceptible only when viewed at very low, almost flat angle at high power [50×], Fig. 9 View Figures 9–14 ). Granules can be rudimentary or reduced to shiny microspots on head and pronotum. • Virtually endemic to the United States, distributed from Atlantic coast to Rocky Mountains, with peripheral populations in far northeastern Mexico and Great Lakes region of southeastern Ontario ( Fig. 15 View Figure 15 ).

Comments. The species of Melanocanthon recognized here are very similar and comprise a cohesive taxonomic group most closely related to the Boreocanthon ebenus - depressipennis species-pair via Melanocanthon granulifer . Linking the two ( Boreocanthon ebenus + depressipennis to M. granulifer ) is the following set of characters: a) strongly, densely granulate dorsal surface essentially lacking punctures; b) base of pygidium impressed on each side of median convexity; c) abruptly widened anterior tibia (inner margin stepped, offset). Separating them are the apomorphic features listed in the diagnosis above.

Horn (1870) was first to report the presence of two apical metatibial spurs in Canthon nigricornis , a character that Robinson (1941) used to group the then known four species as the “nigricornis group of Canthon ,” now Melanocanthon . This feature is unique to Melanocanthon among known Scarabaeinae, although Horn erroneously attributed it also to Canthon indigaceus LeConte (corrected by Blanchard 1885). The mesotibia of Melanocanthon has two apical spurs, like all other known scarabaeine genera except one, the exception being the Brazilian genus Atlantemolanum , which has but one ( González-Alvarado et al. 2019).

The shapes of the anterior margin of the head and margin of the pronotum of Melanocanthon ( Fig. 12 View Figures 9–14 ) are quite consistent among the species; that of the head margin is closely mimicked by the distantly related, South American species, Canthon bispinus Harold ( Fig. 14 View Figures 9–14 ) and very rarely subject to developmental anomaly ( Fig. 21 View Figures 20–26 ). Equally characteristic is the overall ship’s bow-shaped elytral profile ( Fig. 11 View Figures 9–14 ), markedly different from the more evenly rounded shape found in its sister genus, Boreocanthon ( Fig. 13 View Figures 9–14 ).

Observations on the biology of Melanocanthon are scarce and mentioned in the species treatments below. Like Boreocanthon , they are undeniably psammophilous, as noted very early on by Hart (1907) and Vestal (1913), and quite common in open conifer and broadleaf habitats with sandy substrate. For Melanocanthon species, there does not yet exist enough precise ecological data to pursue an analysis of the effect of spatial distribution of sandy habitat on species distributions, such as that by Marshall et al. (2000) for Geoglycosa wolf spiders in the sand ridge system of peninsular Florida. Published comments, as well as my own findings from collection records, suggest an inclination toward fungus-feeding not observed in Boreocanthon ; all species but M. granulifer , have been recorded from bolete basidiomycetes (“toadstools”). Otherwise, collectively the members of the genus exhibit acceptance of a wide variety of food sources, including excrement of many origins, decomposing fruit and carrion.

Melanocanthon is virtually endemic to the continental United States and, in my opinion, unquestionably monophyletic. Known occurrences outside the US are limited to only two cases. I know of a single collection record of M. nigricornis from northern Nuevo Leon, Mexico, but it and M. granulifer are probably both to be found more widely in the far northeastern portion of Mexico. To the north, M. bispinatus is recorded from a few Canadian localities in the far southeastern, Great Lakes region of Ontario. The corporate distribution of the genus ( Fig. 15 View Figure 15 ) suggests an origin and diversification in the eastern United States in varied Pliocene-Pleistocene savanna and woodland habitats. The relatively localized distribution of M. granulifer , as well as its rather striking resemblance to Boreocanthon ebenus , begs the hypothesis of an origin from a Boreocanthon -like ancestor in the more arid western part of its range, where Boreocanthon currently reigns (see Edmonds 2022), and an eastward dispersal into the humid savannas and low forests, where, in the absence of significant competition from its sister genus, diversification occurred.

Mario Cupello (pers. comm.) suggests that the distribution of Melanocanthon ( Fig. 15 View Figure 15 ), especially in the light of its distribution patterns and the sometimes “fuzzy” lines of morphological distinction among its constituent species, supports the idea of recognizing the genus as a superspecies (sensu Mayr 1931, 1963) at a stage when geographical barriers separating allospecies are dissolving and contacts (zones of sympatry) are being established, as could well be the case in the Florida peninsula (see Neill 1957; Howden 1963, 1966 for related commentary). The notion is an attractive context for contemplating the taxonomic relationship between M. bispinatus and M. nigricornis in mid-continent, between M. bispinatus and M. vulturnus / M. punctaticollis in the southeast and between M. nigricornis and M. granulifer in Texas. In the first two cases, definitive identification of M. bispinatus from areas of contact or potential contact ( Fig. 15 View Figure 15 , 19 View Figures 16–19 ) rests primarily on the form of the parameres and secondarily, among other features, on the nature of cephalic and pronotal sculpturing. The case of the taxonomic differences between M. nigricornis and M. granulifer , is somewhat clearer as secondary characters are significantly less variable and, therefore, more reliable identifiers. Nonetheless, these two latter species are undoubtedly very closely related and perhaps should be considered sisters. An analysis of the historical biogeographical and cladistic context for the origin and diversification of Melanocanthon is beyond the scope of this study. Suffice it to say that, given a more robust data set (including molecular data) and more rigorous analytical tools, the genus and its relatives present an attractive opportunity for exploring diversification in North American dung beetles.

A total of five valid species-group names are here assigned to the genus Melanocanthon . They are listed below (original generic placement noted in parentheses). I know of no other available names assignable to the genus.

Melanocanthon nigricornis ( Say, 1823) ( Ateuchus )—valid name

Melanocanthon punctaticollis ( Schaeffer, 1915) ( Canthon )—valid name

Melanocanthon granulifer ( Schmidt, 1920) ( Canthon )—valid name

Melanocanthon bispinatus ( Robinson, 1941) ( Canthon )—valid name

Melanocanthon vulturnus Edmonds, 2023 ( Melanocanthon )— new species

Key to the Species of Melanocanthon Halffter, 1958 View in CoL

Note: Reliability of the key below will be enhanced if target specimens are free or largely so of significant wear and soiling, especially to the dorsal surface, and if accurate locality data are available.

1. Head and pronotum (25×) virtually lacking distinct granulation ( Fig. 20, 22 View Figures 20–26 ), surface uniformly covered by mélange of fine, distinct punctures sometimes accompanied on pronotum by shiny, elongate microspotting; attenuated granulation sometimes perceptible marginally on pronotum. Anterior portion of clypeus with loose, transverse group of 20–25 large, shallow punctures, appearing “freckled” ( Fig. 20 View Figures 20–26 ). Metabasitarsus elongate ( Fig. 26 View Figures 20–26 ), length about 1.5 width at apex, clearly longer than second tarsomere. Peninsular Florida ( Fig. 15–16 View Figure 15 View Figures 16–19 )......... 1. Melanocanthon punctaticollis (Schaeffer) View in CoL

— Pronotum, and usually also head (25×) with at least some distinct, sometimes coarse granulation, with or without distinct puncturing ( Fig. 29 View Figures 27–33 , 53 View Figures 51–58 ). Metabasitarsus variable. Clypeal sculpture variable. Distribution variable................................................................. 2

2. Individuals from localities outside the rectangular area indicated in Figure 19.................... 3 View Figures 16–19

— Individuals from localities within the area enclosed by yellow rectangle in Figure 19.............. 6 View Figures 16–19

3. Species occurring west of about the 88 th meridian, in Illinois and Wisconsin and otherwise west of the Mississippi River ( Fig. 15 View Figure 15 ). Lower apical lobes of parameres flattened, oval tabs ( Fig. 32 View Figures 27–33 , 41 View Figures 34–42 ). Metatarsus wider, length of metabasitarsus about equal to that of second tarsomere, length of apical tarsomere about equal to combined lengths of tarsomeres 3–4 ( Fig. 33 View Figures 27–33 , 39 View Figures 34–42 )................... 4

— Species occurring east of about the 88 th meridian, east of the Mississippi River except Illinois and Wisconsin ( Fig. 15 View Figure 15 ). Lower apical lobes of parameres either small, rounded knobs ( Fig. 49 View Figures 43–50 ), or widened, triangular tabs ( Fig. 56–58 View Figures 51–58 ). Metatarsus slender, length of metabasitarsus usually clearly greater than that of second tarsomere, length of apical tarsomere greater than combined lengths of tarsomeres 3–4 ( Fig. 45 View Figures 43–50 , 55 View Figures 51–58 )..................................................................... 5

4. Pronotum (15×) densely covered with strong, elongated granules on shagreen background ( Fig. 29 View Figures 27–33 ); punctures usually lacking but, if visible, minute (25×) and very widely scattered. Head, elytral interstriae, pteropleura and adjacent metaventrite evenly populated by round granules ( Fig. 27–30 View Figures 27–33 ). Clypeus bearing a loose, transverse array of 8–20 conspicuously large, shallow punctures extending into paraocular areas, appearing “freckled” ( Fig. 27 View Figures 27–33 ). Central Texas ( Fig. 15 View Figure 15 , 17 View Figures 16–19 ).................................................................. 2. Melanocanthon granulifer (Schmidt) View in CoL

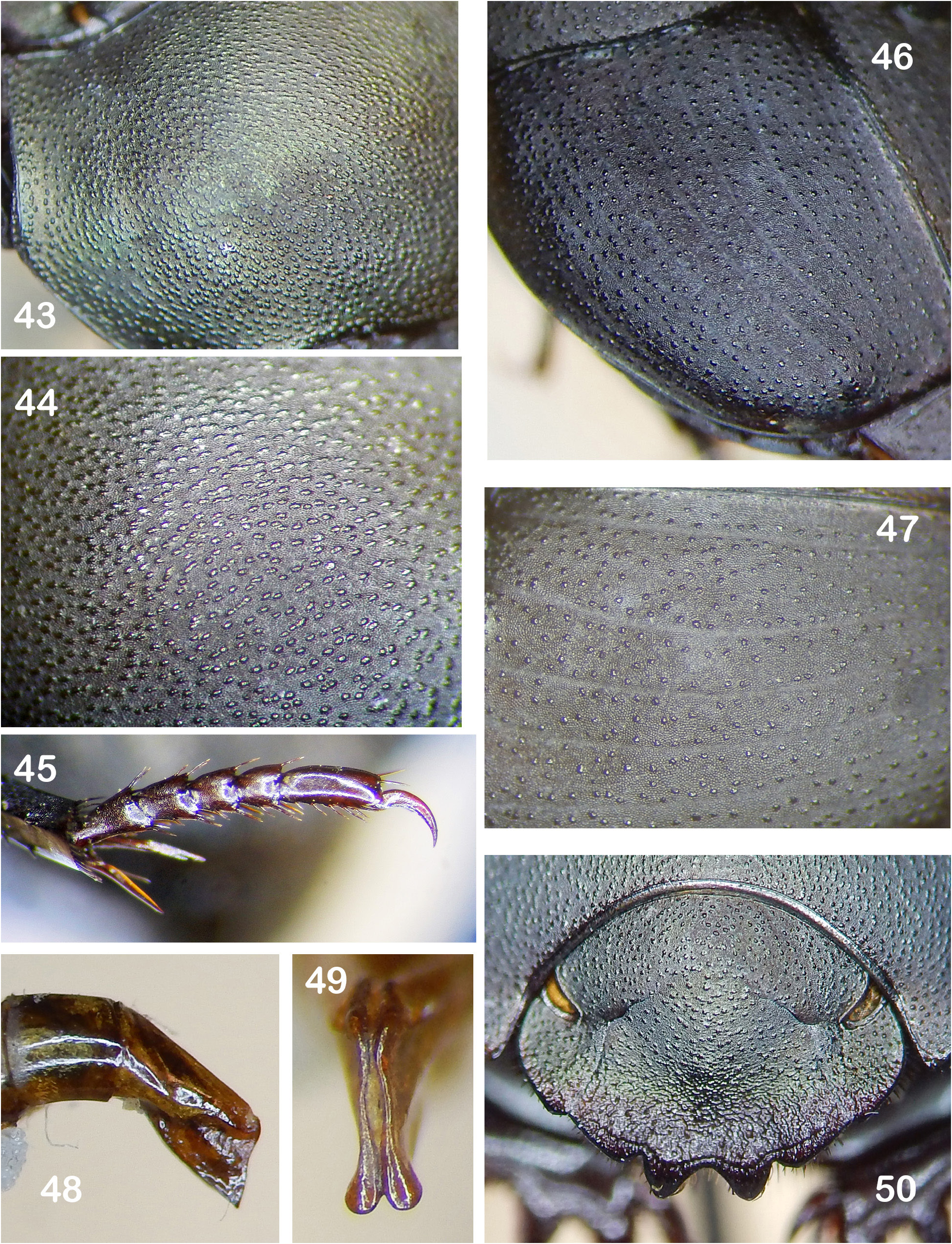

— Pronotum (15×) with distinct puncturing, punctures fine, sharp and evenly dispersed among distinct, usually fine, elongate granules ( Fig. 34–35 View Figures 34–42 ), granules sometimes attenuated and clearly perceptible only when viewed obliquely. Dorsum of head ( Fig. 34 View Figures 34–42 ) finely punctate, almost always lacking conspicuous clypeal punctures and distinct granules except occasional weak granulation near eyes and on paraocular areas. Elytral interstriae 3–6 sparsely granulate, granules small, variable in size and unevenly distributed ( Fig. 36 View Figures 34–42 ) ; pteropleura and adjacent metaventrite ( Fig. 38 View Figures 34–42 ) finely, densely striate, lacking granules. Central United States from Gulf coast to Great Lakes region ( Fig. 15 View Figure 15 , 17 View Figures 16–19 )............................................................. 3. Melanocanthon nigricornis (Say) View in CoL 5. Lower apical lobes of parameres small, convex, oval knobs; apical margins appressed, at most only gently bowed outwardly ( Fig. 49 View Figures 43–50 ). Pronotum (15×) sometimes with dark metallic green surface ( Fig. 43–44 View Figures 43–50 ), often completely dull black ; densely covered with strong, elongated granules on shagreen background; punctures often lacking but, if visible, minute (25×) and widely scattered. Head and elytral interstriae with evenly distributed, uniformly round granules ( Fig. 46–47, 50 View Figures 43–50 ). Florida and adjacent coastal plains of Georgia and South Carolina ( Fig. 15–16 View Figure 15 View Figures 16–19 )................................................................... 4. Melanocanthon vulturnus Edmonds View in CoL , new species

— Expansions (tabs) of lower apical lobes of parameres (viewed caudally) flattened, triangular, with prominent lateral angle, itself curved toward base of genital capsule ( Fig. 56–58 View Figures 51–58 ); apical margins strongly curved outwardly, producing pronounced oval gap between tips of parameres ( Fig. 57 View Figures 51–58 , arrow). Pronotum black ( Fig. 52 View Figures 51–58 ), occasionally with faint green metallic undertones (15×), with distinct puncturing, punctures fine, sharp and evenly dispersed among distinct, usually fine, elongate granules ( Fig. 53 View Figures 51–58 ). Head evenly granulate ( Fig. 51 View Figures 51–58 ); elytral interstriae unevenly granulate, granules small, variable in size and unevenly distributed ( Fig. 54 View Figures 51–58 ). Eastern US north to Ontario, Canada ( Fig. 15–16 View Figure 15 View Figures 16–19 )................................................. 5. Melanocanthon bispinatus (Robinson) View in CoL

6. Lower apical lobes of parameres flattened, oval tabs ( Fig. 41 View Figures 34–42 ). Central portion of head distinctly punctured, almost always lacking distinct granules ( Fig. 34 View Figures 34–42 ). Metabasitarsus about equal in length to second tarsomere ( Fig. 39 View Figures 34–42 ).............................. 3. Melanocanthon nigricornis (Say) View in CoL

— Lower apical lobes of parameres flattened, triangular with prominent lateral angle, itself curved toward base of genital capsule ( Fig. 56–58 View Figures 51–58 ). Head evenly covered by mixture of punctures and coarse granules ( Fig. 51 View Figures 51–58 ). Metabasitarsus usually distinctly longer than second tarsomere ( Fig. 55 View Figures 51–58 )........................................................... 5. Melanocanthon bispinatus (Robinson) View in CoL

| US |

University of Stellenbosch |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Melanocanthon Halffter, 1958

| Edmonds, W. D. 2023 |

Melanocanthon

| Halffter G. 1958: 210 |