Orcinus orca (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6610922 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6608638 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/BD4CCC61-7625-FFEB-FFDB-FE4FE1F7FE11 |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Orcinus orca |

| status |

|

9. View On

Killer Whale

French: Epaulard / German: Schwertwal / Spanish: Orca

Other common names: Orca

Taxonomy. Delphinus orca Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL ,

“Oceano Europo.”

Although O. orca is currently recognized as monotypic, serious taxonomic revision is required and will likely occur in the near future. Genetic, morphological, and ecological evidence indicates that there are three ecotypes (residents, transients, and offshores) in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean, which may represent separate species or subspecies. Three distinct ecotypes have also been identified in Antarctic waters (types A, B, and C) that may correspond to putative species previously proposed in the 1980s ( O. nanus and O. glacialis ). Recent molecular studies strongly suggest that these three ecotypes warrant species designation. A fourth type (type D) has also been newly described from New Zealand area. Monotypic.

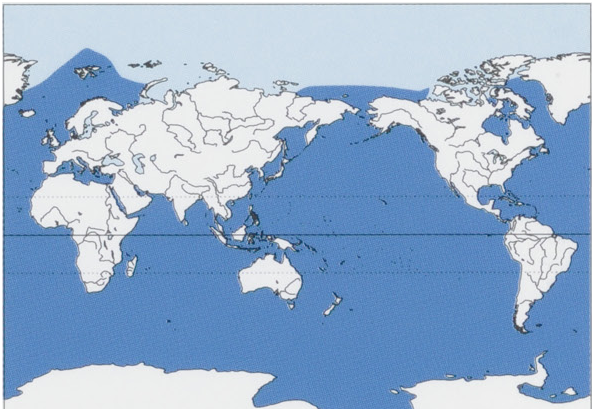

Distribution. The most widely distributed of all cetaceans, found in almost any marine environment from the Equator to both polar zones, including semi-enclosed seas such as the Mediterranean Sea, Red Sea, Persian Gulf, Gulf of California, Sea of Okhotsk, Yellow Sea, Sea ofJapan, Chukchi Sea, Beaufort Sea, Gulf of Saint Lawrence, and Ross Sea. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Total length up to 980 cm (males) and up to 770 cm (females); weight up to 6600 kg (males) and up to 4700 kg (females). Neonates are 210-260 cm long and weigh 160-180 kg. The Killer Whale is the largest member of Delphinidae and is one of the most distinctive and easily recognizable cetaceans. Body is robust but streamlined, with tall dorsal fin, large paddle-shaped flippers, and blunt, poorly defined beak. It is strongly sexually dimorphic in size and morphology. Females and immature individuals have falcate dorsal fins, which may have slightly rounded tips. Adult males have much taller (up to 180 cm) dorsal fins than females (up to 80 cm) that are triangular in shape and may slant slightly forward in some geographical forms, giving the appearance of backward placement. Adult males also have larger flippers than females, and fluke tips of some older males are curved downward. Lowerjaw and ventral area up to urogenital region is white, with two lobes curving up onto flanks anterior to genital slit and behind dorsal fin. Undersides of flukes are also white, and there are white patches above eyes. Rest of body is black except for gray saddle patch behind dorsal fin. Some geographical forms have distinctive gray line extending from lower point of saddle patch toward head, making a curved “cape” shape. Young individuals tend to have a more muted pattern, with white areas tinged slightly yellow or orange. There are 10-14 pairs of large, conical teeth (up to 10 cm long) in each jaw, although they may be worn down and damaged in older individuals. There are three ecotypes known from north-western coasts of North America, including Alaska. REsI-DENT. The resident Killer Whale has dorsal fin with rounded tip, medium-sized oval eye patch oriented horizontally, no distinct cape pattern, and saddle patch that can be open (with black pigmentation incurring into gray saddle) or closed, with tip extending no further than middle of dorsal fin base. TRANSIENT. The transient Killer Whale is generally larger in size than the resident Killer Whale, has pointed dorsal fin tip, no dorsal cape pattern, medium-sized oval eye patch oriented horizontally, and closed saddle patch with tip that can extend as far forward as anterior edge of dorsal fin base. OrrsHORE. The recently described offshore Killer Whale is genetically distinct from, but similar in appearance to, the resident form, although it tends to be smaller and females have rounded dorsal fin tips. Three morphologically, ecologically, and genetically distinct types have also been identified in Antarctic waters. Type A. This type of Killer Whale is circumpolar in Antarctic waters and is similar in appearance to forms in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean. Tyre B. This type of Killer Whale is known primarily from Antarctic and subantarctic waters and is generally smaller than the type A Killer Whale. This type possesses dorsal cape pattern, large horizontally oriented eye patch, and closed saddle patch. A build-up of diatoms on skin may give white areas a yellowish hue. Type C. This type of Killer Whale is a dwarf form, reaching average lengths 1-3 m shorter than the other types and is restricted to Antarctic waters. Like the type B Killer Whale, type C has distinct dorsal cape, generally closed saddle patch, and pale yellow patches. Eye patch, however, is small and slanted at 45° angle to horizontal body axis. A fourth type (TYPE D) has been described very recently from a mass stranding event on New Zealand in 1955 and several sightings at sea since 2004. An extremely small eye patch characterizes this type.

Habitat. Cosmopolitan in marine habitats but somewhat more abundant at higher latitudes and in near-shore waters, especially in regions of high productivity. The Killer Whale has been documented, on rare occasions, to move into river mouths. Most observations have been within 800 km of shoreline. The Killer Whale is less abundant in lower tropical latitudes and in the ice-pack zones of the high Arctic and Antarctic oceans. In the Canadian Arctic Ocean, however, the Killer Whale is becoming seasonally more abundant as pack-ice extent and duration decline with global climate change. Resident, transient, and offshore forms of Killer Whales are most well known from populations on the north-western coast of North America, including the Aleutian Islands, and there is good evidence to suggest that, in that area at least, they may each warrant full species status. Resident Killer Whales are the most near-shore distributed of the three forms, given that they feed primarily on salmon migrating into freshwater areas to spawn. The type B Killer Whale is found primarily in Antarctic regions, usually among ice floes concentrated around the Antarctic Peninsula, although their distribution may extend up to the Falkland Islands and New Zealand. The type CKiller Whale appears to be restricted to Antarctic waters and prefers the pack-ice habitats in eastern Antarctica. The recently described type D Killer Whale is subantarctic and is most abundant between 40° S and 60° S.

Food and Feeding. The Killer Whale is an apex predator. Globally, it is a generalist with a diverse diet. There are over 140 species of documented prey including a wide variety of small and large fish, cephalopods, marine mammals, seabirds, and marine turtles. The Killer Whale is the only cetacean species known to have populations that specialize on mammal prey. Over 50 different species of mammals have been documented as prey including cetaceans, pinnipeds, sirenians, mustelids, and occasionally even ungulates and ursids. On a local scale, populations of Killer Whales are often distinguished by dietary specializations. For example, resident Killer Whales in the north-western coast of North America feed almost exclusively on salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) and are not known to feed on endothermic animals. They appearto prefer the largest and most fat-rich species (Chinook salmon, O. tshawytscha, and Cohosalmon, O. kisutch), despite smaller species such as sockeye salmon (0. nerka) occurring in greater abundance. Transient Killer Whales in the same area, by contrast, hunt marine mammals and do not consume fish. Preferred prey include Harbor Seals (Phoca vitulina), Harbor Porpoises ( Phocoena phocoena ), and Dall’s Porpoises ( Phocoenoides dalli), and they will also eat Steller Sea Lions (Eumetopiasjubatus), California Sea Lions (Zalophus californianus), Northern Elephant Seals (Mirounga angustirostris), Pacific White-sided Dolphins ( Lagenorhynchus obliquidens ), and Common Minke Whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata). Transient Killer Whales off the coast of California specialize on Gray Whales (Eschrichtius robustus) and will attack young that are accompanying their mothers northward on their first migration. Dietary preference of offshore Killer Whales is currently poorly known but appears to include more offshore fish species such as Pacific halibut (Hippoglossus stenolepis) and various carcharinid sharks. Resident, transient, and offshore killer whales, although partially sympatric in their distributions, do not appearto associate with each other and are unambiguously distinct in mtDNA and nDNA composition. Given their dietary specializations, this genetic divergenceis likely the result of foraging strategies being socially passed across generations. This would have eventually given rise to divergent enough skill-sets so as to underlie mutually exclusive lifestyles, making for an intriguing and rare case where ecological divergence is likely driving incipient sympatric speciation. Populations of Killer Whales that inhabit Norwegian fjords specialize on herring ( Clupea spp. ) and behaviorally resemble resident Killer Whales in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean. The Antarctic type A Killer Whale specializes on the Antarctic Minke Whale (B. bonaerensis), and type B populations in the vicinity of New Zealand may specialize on sharks and other elasmobranchs. The type C Killer Whale feeds primarily on Antarctic fish species, and some populations of type D Killer Whale are thought to prefer Patagonian toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides). In the Canadian Arctic, Killer Whales most commonly prey on the Beluga (Delphinapterusleucas) , the Narwhal ( Monodon monoceros), and the Bowhead Whale (Balaena mysticetus). In multiple populations, dietary specialization has led to development of unique foraging strategies. For example, Norwegian populations of Killer Whales use a strategy called “carousel feeding,” during which a school ofherring is herded into a tight ball near the water’s surface. Individual whales then stun and pick at prey around edges of the ball. Killer Whales in the Strait of Gibraltar feed on Atlantic bluefin tuna ( Thunnus thynnus) by chasing schools for ¢.30 minutes at high speed until tuna are exhausted. Transient Killer Whales usually hunt in small groups and are more acoustically quiet than resident Killer Whales, likely to keep from alerting their mammalian prey. Killing seals and sea lions usually involves repeated ramming, slapping them with flukes, or even leaping on them. After prey is stunned,it is dragged underwater and drowned. The killed animal is then shared among the group. Killer Whales may herd large groups of dolphins or porpoises into confined bays where they can be easily killed after being trapped (a strategy that is disturbingly reminiscent of human dolphin drives). Larger groups of transient Killer Whales are required to successfully attack mysticetes and the Sperm Whale (Physeter macrocephalus). The group will coordinate itself so that some individuals grasp flippers and tail flukes of prey to impede movement while others gash at the blowhole area to impair breathing. Blubber,lips, and tongue are usually the only parts of the killed whale that are consumed. Groups of type B Killer Whale in Antarctica have learned how to coordinate forceful water waves to wash over and tilt ice floes to dislodge Weddell Seals (Leptonychotes weddelliz) resting on them. When this wave-washing technique fails, one or two Killer Whales may even lift the ice floe with their heads to flip it over or break it. Killer Whales off Patagonia, Argentina, have developed a strategy for hunting young Southern Elephant Seals (Mirounga leonina) and South American Sea Lions (Otaria byronia) that involves intentionally stranding themselves temporarily on the sloping beaches. Killer Whales around the Crozet Islands use a similar method, and in this region, there is compelling evidence to suggest that adults actively teach this strategy to their offspring.

Breeding. Off the Pacific coast of North America, breeding peaks in October—March but may occur throughout the year. In the north-eastern Atlantic Ocean, breeding peaks between late fall and mid-winter. Most life history data are drawn from resident Killer Whales in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean and may not be typical of all populations of Killer Whales. Mating is endogamous in resident Killer Whales, occurring when males briefly leave their matrilines to mate with females from other pods within the same social clan, usually during on temporary merging of pods (superpod). Clans are culturally distinguished by different vocal dialects that reflect the degree to which pods and matrilines are related and may serve as important communicative cues for avoiding inbreeding. Gestation period of the Killer Whale is one of the longest among mammals, lasting 15-18 months, and the birthing interval lasts c.5 years. Young are weaned at 1-3 years of age and reach sexual maturity at 10-15 years for females and c.15 years for males. Males do not reach full physical maturity until c.21 years. Males may live up to 50-60 years, and females may live up to 80-90 years. Females will give birth to an average of five viable offspring during their lifetimes and become menopausal at c.40 years. The Killer Whale is one of only a handful of mammalian species, including humans, with well-documented, post-reproductive female longevity. As a species with a matrilineal social structure, post-reproductive female longevity may contribute fitness benefits to offspring and grand-offspring via amassed stores of socially transferrable knowledge. Such knowledge could include long-term awareness of prey distribution and movements. Socially derived survival advantages that are dependent on long-term memory stores or experience thus provide evolutionary pressure forfemales to live beyond reproductive age.

Activity patterns. Foraging and traveling are the most common behaviorsin all studied populations of Killer Whales. Resident Killer Whales spend a much higher proportion of their time foraging and traveling (90-95%) than do transient Killer Whales (60-70%) that spend more time socializing and resting. Herring-specialist populations of Killer Whales off northern Norway have an activity budget very similar to that of resident Killer Whales in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean, suggesting that the proportion of time spent traveling and foraging depends heavily on preferred prey type. Resident Killer Whales have seasonal inshore—offshore movements associated with migrating salmon and forage in bouts of 2-3 hours. Pods move in a consistent direction at a mean swimming speed of ¢.6 km/h, with individuals widely spread out. Caught prey may be shared among small subgroups or among mothers and offspring. Resident Killer Whales tend to be vocally quiet while foraging, repeating discrete calls drawn from an average repertoire of twelve call types per pod. Diving patterns of transient Killer Whales vary throughout the day. Generally, deep dives are more frequent during the day and shallow dives are of longer duration during the night. When traveling, Killer Whales will orient themselves in a line abreast and move in a single direction at a fast pace of up to 20 km/h. Dives may be synchronized. When resting, Killer Whales will also swim in a line abreast but at slower speeds and spaced more tightly together. Vocalization is minimal, and dives will be synchronized and regular, with long dives of 2-5 minutes separated by a series of 3—4 short dives. Resting groups may also be stationary. The Killer Whale is known to be aerially active; breaching, spy hopping, and fluke and flipper slapping are common. Resident Killer Whales in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean regularly visit kelp beds and shallow pebble beaches, where individuals will intentionally rub their bodies through kelp fronds or along smooth pebbles on the sea floor. This behavior seems to be social and apparently pleasurable.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Populations of Killer Whales known from the West Coast of North America have one of the most stable societies known among non-human mammals. Social structure is matrilineal, with a clearly defined hierarchical organization. The most basic social tier is the matriline, which usually consists of fewer than ten individuals that are all linked by direct maternal descent (a matriarch and up to four generations of her descendants). Matrilines are highly stable, and members are rarely seen separated for more than a few hours. Among resident Killer Whales, there are no documented incidents of individuals permanently dispersing from their natal matrilines. Groups of usually 1-3 related matrilines form the next social tier, the pod. Pods, which among resident Killer Whales may contain 1-55 individuals, are less stable, and their comprising matrilines may separate for weeks or months at a time. Nevertheless, matrilines still tend to travel more often with other matrilines from within their own pod than outside of it. The third social tier is the clan, which consists of pods that all have similar vocal dialects. These dialects are a reflection of maternal ancestry and are considered to be a good example of a non-human cultural tradition (a socially learned behavior that is consistently passed across generations). A clan dialect likely originates from a common ancestral pod, and within-clan pods are more closely related than between-clan pods with different dialects. Offspring learn dialects from their mothers through vocal imitation. Clans are sympatric, however, and mixed-clan aggregations of pods are common. Dialects have also been documented among herring-specialist Killer Whales off northern Norway and likely also exist in other less-studied populations. For example, dialects and matrilineal structure were recently described for a population of Killer Whales in Avacha Gulf, Russia. There are few data on how clans are related to each other and on how they may have originated. The last socialtier is the community, which is defined by pod association patterns, not clan membership (i.e. not maternal ancestry or dialect). Pods may often associate with other pods from different clans, but they rarely associate with other pods from outside their community. There are three communities of resident Killer Whales in the northeastern Pacific Ocean: southern residents (three pods, one clan), northern residents (16 pods, three clans), and southern Alaskan residents (eleven pods, two clans). The social structure oftransient Killer Whalesis less understood. Transient Killer Whales also have matrilines, but individuals disperse from them much more frequently and for longer periods of time than individuals in populations of resident Killer Whales. Matrilines of transient Killer Whales thus tend to be smaller (pods often consist ofless than ten individuals), and observing single individuals is more common. Communities of transient Killer Whales do not have group-specific dialects, which is likely due to their less stable social organization not being conducive to the development ofspecific cross-generational learned behaviors. Associations among matrilines of transient Killer Whales are also less consistent than they are for resident Killer Whales, so matrilines do not form identifiable pods. Large-scale social stability is still evident, however, and communities of matrilines of transient Killer Whales are distinguishable by their preferred within-community association. There are three communities of transient Killer Whales in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean. Although social structure has been less thoroughly studied in other populations of Killer Whales, matrilineal organization is likely typical of the species. There are few documented regular migration patterns, but individuals may move overlarge distances. Resident Killer Whales off the coasts of British Columbia, Canada, and Washington, USA, have movements that typically span 630 km. Antarctic and North Atlantic populations of Killer Whales move seasonally with advancing and receding pack ice. Herring-specialist populations migrate between Norwegian and Icelandic waters, following herring schools, and Killer Whales off Patagonia, Argentina, become more abundant during breeding peaks of the Southern Elephant Seal in December and March-May. Some Antarctic populations of Killer Whales may also migrate to lower latitudes seasonally, following migrating Antarctic Minke Whales. Populations of the type B Killer Whale may make periodic “maintenance” migrations into subtropical waters (30-37° S) to allow skin regeneration without as much heat loss. Transient Killer Whales tend to have larger home ranges than resident Killer Whales. For example, groups of transient Killer Whales may travel up to 2600 km between California and Alaska. The maximum known movement of an individual Killer Whale is 5500 km; over a period of years, it was identified in both Baja California and Peru.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Data Deficient on The [UCN Red List. Minimum worldwide abundance of the Killer Whale is ¢.50,000 individuals, based on regions that have been surveyed so far, but the total abundance is likely higher. The Data Deficient status will need reevaluation when taxonomy of the Killer Whale changes in the near future. There are ¢.25,000 individuals in Antarctic waters south of 60° S, ¢.119 individuals in New Zealand waters, ¢.30 individuals identified off Argentina, ¢.8500 individuals in the eastern tropical Pacific, ¢.1500 individuals in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean (c.251 Aleutian Islands transients, ¢.991 Aleutian Islands residents, c.314 west coast transients, c.211 offshores, ¢.216 northern residents, and c.90 southern residents), ¢.2000 individuals in Japanese waters, ¢.86 individuals off the Baja Peninsula, c.430 individuals in Hawaiian waters, 700-800 individuals in Russian waters, 133 individuals in the northern Gulf of Mexico, 3100 individuals in Norwegian waters, and ¢.6618 individuals in waters off Iceland and the Faroe Islands. Because many populations of Killer Whales are localized and have highly specialized behaviors, they may be especially vulnerable in certain areas. For example, the population near the Strait of Gibraltar is threatened due to low abundance (less than 50 individuals) and declines in bluefin tuna stocks, which are their primary prey. The southern resident Killer Whale community in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean is listed as Endangered under the Endangered Species Act (USA) and Species at Risk Act (Canada) due to recent population decline. This was driven largely by targeted removals of young females (63 individuals in total) for captive display in 1964-1977. In the past, the Killer Whale was a small-scale target of commercial and subsistence whaling. Soviet whalers took 26 ind/year on average in 1939-1975. Currently, Killer Whales are killed in small numbers in fisheries offJapan, Greenland, Indonesia, and the Caribbean islands. The Killer Whale may also be injured or killed on purpose by fishermen to reduce interference with fisheries, and in the past, especially out of fear—a persecution similar to that suffered by sharks and Wolves (Canis lupus). This fear was likely a result of the Killer Whale’s diverse diet, particularly of the mammal-eating specialists, and is reflected in the species’ common name. Norway killed an average of 56 Killer Whales/year in 1938-1981 to deliberately reduce competition with local fisheries, and fishermen in Alaskan waters continue to opportunistically shoot Killer Whales to prevent interference in long-line fisheries. Killer Whales will often follow fishing vessels, sometimes for long periods. In the Bering Sea, for example, a single pod followed a fishing vessel for 31 days covering 1600 km. In waters north of Scotland, Killer Whales approach mackerel fishing boats during net retrieval to feed on escaped catch, butso far, there has been no evidence of accidental entanglement. Reduced prey availability is also a threat to the Killer Whale. For example, recent declines of Chinook salmon stocks in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean due to overfishing and spawning ground degradation are threats to the local communities of resident Killer Whales. Vessel collisions in areas of high traffic, especially from careless whale-watching operations, may also be a problem. The Killer Whale is a particularly charismatic cetacean and an extremely popular whale-watching subject, and increased vesseltraffic in their vicinity may disturb normal activities by reducing resting and foraging. Underwater noise from numerous vessel engines can also mask echolocation and social signals. The Killer Whale is currently one of the most common and iconic features of aquaria, and it is often taken in live captures. This contributed to the depletion of the population of southern resident Killer Whales. In the 1970s and 1980s c.50 individuals were taken from Icelandic populations for captive display, and Killer Whales are still occasionally caught and sold in the captive industry (along with other species of ocean dolphin) during controversial Japanese dolphin drives operating in Taiji. Pollution is another threat to Killer Whales. The Exxon Valdez oil spill contributed to a 33% loss in a pod ofresident Killer Whale and 41% loss in a group of transient Killer Whales. The pod has not recovered, and the group continued to decline and is now depleted. As a top predator, the Killer Whale also suffers from contamination from bioaccumulation of persistent organochlorines. Transient and southern resident killer whales in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean are, in fact, the most PCB-contaminated marine mammals in the world, although levels have been declining gradually in recent years. Use of PBDEs in flame-retardants, however, has led to recent, rapid increases in concentrations of PBDEs in body tissue of cetaceans, including the Killer Whale. In southern resident Killer Whales, for example, tissue concentrations of PBDEs are predicted to rise in the near future. Populations of Killer Whales in northern Norway have tissue concentrations of PCBs similar to Killer Whales in the north-eastern Pacific Ocean and also have very high levels of PB-DEs. Japanese populations of Killer Whales appear especially contaminated with DDT. Accumulated high concentrations ofthese persistent organochlorine pollutants are known to have immunosuppressive effects and reduce reproductive success.

Bibliography. Baird (2000), Barrett-Lenard (2000), Bigg et al. (1990), Dahlheim & Heyning (1999), Durban & Pitman (2012), Erbe (2002), Ford (2009), Ford & Ellis (2006), Ford, Ellis & Balcomb (2000), Ford, Ellis, Barrett-Lennard et al. (1998), Guerrero-Ruiz et al. (2005), Guinet & Bouvier (1995), Guinet et al. (2007), Hickie et al. (2007), Higdon et al. (2012), Hoelzel et al. (1998), Ivkovich et al. (2010), Jefferson et al. (2008), Kajiwara et al. (2006), LeDuc et al. (2008), Luque et al. (2006), Lusseau et al. (2008), Matkin et al. (2008), Miller et al. (2010), Mongillo et al. (2012), Morin et al. (2010), Pitman & Durban (2012), Pitman & Ensor (2003), Pitman, Durban et al. (2011), Pitman, Perryman et al. (2007), Reeves et al. (2003), Riesch et al. (2012), Ross et al. (2000), Taylor et al. (2008a), Williams & Lusseau (2006), Williams et al. (2006).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.