Pliopapio alemui, FROST, 2001

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1206/0003-0082(2001)350<0001:NEPCMP>2.0.CO;2 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/780B87DF-0827-FA38-FF6E-FA5A06E4FC79 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Pliopapio alemui |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Pliopapio alemui , new species

SPECIFIC DIAGNOSIS: As for genus.

ETYMOLOGY: Named in honor of Alemu Ademassu, Paleoanthropology Laboratory curator at the National Museum of Ethiopia responsible for assisting with preparation, molding, and study of all Middle Awash specimens.

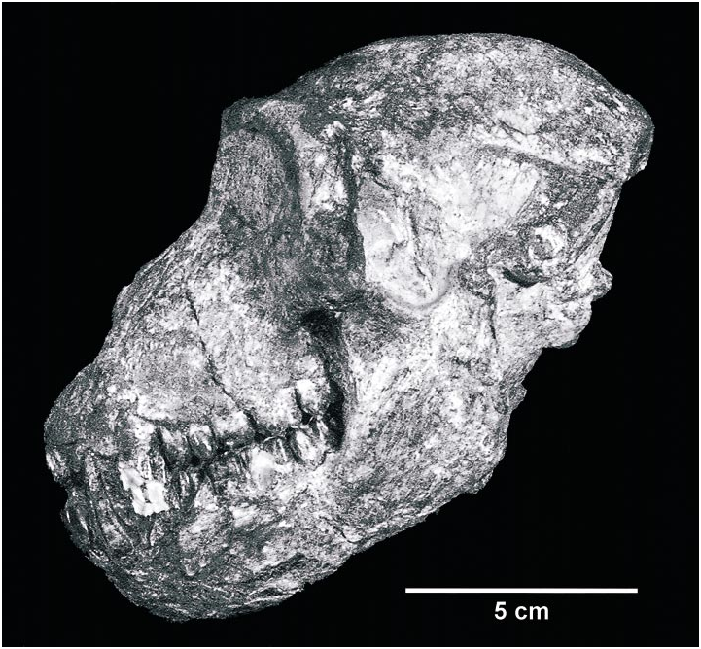

HOLOTYPE: ARAVP6/933. A nearly complete male cranium and attached mandible

with complete but damaged dentition, found by Awoke Amzaye in December 1995.

HYPODIGM: See appendix 1.

HORIZON: All specimens are derived from the Aramis Member of the Sagantole Formation, between the GATC and DABT, and are therefore dated to 4.4 Ma (Renne et al., 1999).

DESCRIPTION: The most complete specimen is the holotype male skull ARAVP6/ 9332 (see fig. 1). The mandible is attached to the cranium by a thin layer of matrix that prevents the two from being safely separated. Therefore, the palate and much of the cranial base are not available for observation. Of the main cranial regions, only the left zygomatic is completely missing. The right orbit is damaged and lacks much of the right half, except for one triangular portion around the zygoma. The right zygomatic arch is mostly present, but crushed, missing only the region around the temporojugal suture. The right maxilla and mandible are weathered, revealing the roots of the teeth. The other cranial specimens are all considerably more fragmentary. ARAVP6/437 (see fig. 2) is a partial right male maxillary fragment with the dorsal surface up to the piriform aperture, the roots of the canine and fourth premolar, and complete central incisor and third premolar. ARAVP1/1723 (fig. 2) is a partial right female maxilla preserving the canine through third molar. ARAVP1/1007 (fig. 2) is a slightly crushed left female premaxillomaxillary fragment with the rostral surface preserved nearly to the lateral border of the piriform aperture, a damaged lateral incisor, and complete canine through first molar.

Pliopapio alemui is smaller in cranial size than all known Theropithecus and Papio , other than P. hamadryas kindae , P. angusticeps , and P. izodi , to which it is similar in size. It is sightly larger than all but the largest Macaca , such as M. thibetana and M. nemestrina . This cranial size estimate is confirmed by centroid sizes computed from a sample of 45 cranial landmarks (see fig. 3). In dental size, it is marginally smaller than Parapapio ado from Laetoli and Kanapoi,

2 Sex identifications throughout the text are based upon the highly dimorphic size and morphology of the upper and lower canines and the lower third premolar.

and similar to specimens from Ekora, the Lomekwi Member of the Nachukui Formation, the Tulu Bor Member of the Koobi Fora Formation, and Unit 2 of the Chiwondo beds. Dental dimensions for Pl. alemui are listed in table 1.

Rostrum. The infraorbital foramina are only preserved on the left side of ARAVP 6/933. The four foramina are arranged in a superolaterally concave arc, as in Theropithecus (Eck and Jablonski, 1987) . Relative to the orbit they lie roughly in midmediolateral position and are placed more closely to its inferior rim than in Theropithecus .

In ARAVP6/933 and ARAVP6/437 there is little to no development of maxillary ridges, similar to Parapapio (Freedman, 1957) , Theropithecus (Theropithecus) (sensu Delson, 1993), and most Macaca , but dis tinct from Papio and Mandrillus . The maxillary fossae are also extremely shallow. Once again, this is similar to the above genera and to Papio (Dinopithecus) (see Delson and Dean, 1993). From what is preserved in ARAVP1/1007 and ARAVP1/1723 the females seem to lack these structures as well.

The muzzle dorsum of ARAVP6/933 is largely smooth and saddleshaped, as it is in Theropithecus oswaldi . It is concave in the sagittal plane and forms a convex arc in paracoronal cross section at the level of the second molar. This cross section is sharper, however, with the nasals forming a more acute angle than they do in T. oswaldi . This is clos er to the cross section of Macaca mulatta , M. nemestrina , or M. thibetana , but with a relatively longer muzzle. When viewed laterally the muzzle profile is concave from gla Fig. 1 View Fig . Continued. bella to rhinion, displaying an antorbital drop, and is also concave from rhinion to nasospinale, and finally convex from nasospinale to prosthion. While the entire muzzle is quite long and not unlike that of Papio , the length of the segment from glabella to rhinion comprises less of the total muzzle length than it does in Papio (see fig. 4). Rhinion is also considerably more prominent than in Papio or Theropithecus .

The sutures of the muzzle are well preserved on the left side of ARAVP6/933 and on ARAVP6/437. The premaxillomaxillary suture follows the superior portion of the na sal aperture at a margin of approximately 4 mm, as it does in most larger papionins. Unlike in T. gelada , it does not enter the piriform aperture. The nasal process of the premaxilla projects further posteriorly than it does in Papio , approaching to within 1.5 cm of the orbits. The premaxillomaxillary suture is therefore largely an anterolaterally smoothly curving arc. The premaxillae project relatively far anteriorly beyond the canine, and there is a modest diastema separating the canine from the incisors (6.5 mm on the left side of ARAVP6/933).

When viewed superiorly, the muzzle is much narrower than the neurocranium (see fig. 5). In comparison to the length of the neurocranium, the muzzle is longer than in most Macaca or Parapapio and shorter than in Papio (Papio) and Mandrillus (see fig. 6). The muzzle of the female ARAVP1/1007 is considerably shorter than that of the male ARAVP6/933. When they are lined up at the first molar, the mesial edge of the lateral incisor of ARAVP1/1007 is even with the middle of the canine of ARAVP6/933.

The piriform aperture is preserved in ARAVP6/933, partially preserved in ARA VP6/437, and only a small portion is preserved in the female ARAVP1/1007. The outline of the piriform aperture is typically papionin, being roughly ovoid but forming a V at its inferior pole. In breadth it is slightly narrower than that of Papio . The nasals of ARAVP6/933 are distorted, but probably would have formed a straight superior margin. The premaxillae then bow gently laterally to the aperture’s widest point just above the roots of the incisors, then curve convexly to meet at nasospinale in a relatively acute inferior angle. There is no evidence of anterior nasal tubercles.

The maxillary dental arcade is preserved in ARAVP6/933, and it is preserved from C to M 3 in ARAVP1/1723 and from I2 to M 1 in ARAVP1/1007. The dental arcade is somewhat distorted in ARAVP6/933, but appears to have been largely Ushaped, with the canines marking the bases of an anterior arc composed of the incisors. The alveolar margins appear to be gently bowed laterally,

TABLE 1 Dental Measurements for Pliopapio alemui and Kuseracolobus aramisi

with their widest point at the mesial loph of M2 and narrowest at P3, bulging laterally again at the canine, although less so in the females ARAVP1/1007 and ARAVP1/ 1723. The molar series forms a short arc, with the M2 oriented slightly obliquely. The premolars are set in a straight line from M1 to C.

When viewed laterally, the maxillary dentition in ARAVP6/933 and ARAVP1/ 1723 is basically straight to very slightly concave, as in most cercopithecines. The palate is preserved in ARAVP6/933, but it is covered in matrix (which cannot be removed without causing damage to the specimen). ARAVP1/1723 preserves a small part of the palatal process, which is about 0.5 cm in depth anteriorly and deepens slightly posteriorly.

Zygomatic Arch. The maxillary root of the zygomatic arch arises from above the distal loph of M 2 in the male ARAVP6/933 and above the mesial loph of M 2 in the female ARAVP1/1723. This is farther anterior than in Papio , Gorgopithecus , and Theropi thecus (other than T. gelada and T. oswaldi leakeyi ). ARAVP6/933 is the only specimen to preserve the zygomatic arches. The anterior surface of its zygoma curves gradually and smoothly superoposteriorly, with only a very slight depression in the region of the infraorbital foramina and maxillozygomatic suture. This depression is unrelated to any maxillary fossae and is the only feature to interrupt the otherwise smoothly curving surface. The inferior margin of the anterior portion of the zygomatic arch is a smooth semicircular curve interrupted by a small pyramidal process where the maxillozygomatic suture intersects. The superiormost point of the inferior margin lies below the lateral edge of the orbit, at which point the zygoma curves inferiorly again. The temporal surfaces do not appear strongly excavated as in Theropithecus , but there is some damage and distortion here.

In superior view, the zygomatic arches are no more laterally flared than in most Macaca or Papio , but are more smoothly curved. This is particularly notable anteriorly where they are more posteriorly angled than in Papio . The zygomata of the latter genus jut out more sharply, perhaps due to greater maxillary fossa development. The scar for the origin of the masseter muscle is visible in ARAVP6/933 and terminates anteriorly very close to the maxillozygomatic suture. The posterior termination is not preserved, but must have been anterior to the zygomaticotomporal suture as there is no scar on the zygomatic process of the temporal.

Orbital Region. The orbital region is only preserved in ARAVP6/933. Internally both orbits are occupied by matrix. The supraorbital torus is relatively prominent, but thin superoinferiorly. It is mildly Vshaped in superior view and separated from the neurocranium by a broad ophryonic groove. Unlike in Papio , T. oswaldi , and larger Macaca , there are no bulges above the torus at the midpoints of the orbits. In frontal view, the superior orbital rim and torus rise only very slightly lateral to the sagittal plane, then curve inferiorly, giving the torus a mildly superiorly bowed surface and the orbits a slightly laterally ‘‘drooping’’ appearance. There are no supraorbital notches.

The interorbital breadth is narrow, and glabella is not prominent. There is some damage in this area, but nasion was probably the anteriormost point on the frontal. The orbits themselves are largely mediolaterally oval in outline, being relatively short and broad. The lacrimomaxillary suture seems to lie just at the orbital rim, and the lacrimal fossa was likely contained entirely in the lacrimal bone.

Calvaria. The calvaria is only preserved in ARAVP6/933. It is relatively globular in overall shape, with its greatest width at the external auditory meatus. It is generally lacking in superstructures and is considerably broader than the muzzle. When viewed in Frankfurt horizontal, the frontal bone rises above the supraorbital torus and achieves its maximum height about 1 cm anterior to bregma. The cranial vault remains at this height until about 2.5–3 cm posterior to bregma. The temporal lines are faint and widely separated, curving posteriorly less than 1 cm medial to the lateral orbital margins. Poste rior to this, they remain subparallel, approximating only slightly posteriorly. In conjunction with the weak temporalis development, postorbital constriction is slight and the temporal fossae are narrow. The nuchal crests are slight to nonexistent at inion, but become rather large laterally, having their greatest width behind the external auditory meatus. Viewed posteriorly, the vault is taller than that of Theropithecus , which is broad and low, but is similar to that of Papio or Macaca .

Basicranium. The basicranium of ARA VP6/933 is largely covered in matrix, and the foramen magnum is obscured by an articulated atlas. The occipital plane is probably inclined at about 45° in Frankfurt orientation. The mastoid processes do not appear to be prominent. The postglenoid processes may be closely approximated to the glenoid fossae, but this is difficult to tell, and it is impossible to see whether they are separated by a sulcus, as in T. oswaldi darti . The external auditory meatus are basically normal to the sagittal plane and appear nearly round in cross section.

Facial Hafting. The only specimen where the relationship between the face and neurocranium can be assessed is ARAVP6/ 933. The glenoid fossa lies closely in line with the alveolar plane. The glenoid fossa is only slightly more elevated than in Papio , but less so than in Theropithecus . Its position is not unlike that in Parapapio cf. jonesi from Hadar (see Szalay and Delson, 1979: 345). The face is less klinorhynch than that of Papio (Papio) , but also less airorhynch than that of Theropithecus gelada .

Mandible. ARAVP6/933 preserves most of the mandible, with considerable damage to the right side. ARAVP1/73 (see fig. 7) is a male mandible with most of the corpora and symphysis intact. The inferior margin is missing posterior to the symphysis. The complete dentition is present other than the left canine through right i1. ARAVP1/133 (see fig. 7) is a considerably distorted and crushed female mandible lacking the left ramus, but preserving most of the right. The inferior margins are largely intact, and the left and right p4m3 are present. ARAVP1/1006 (see fig. 7) preserves separate and partially crushed female right and left corpora with all of the dentition other than the right central incisor through the left canine. ARAVP1/ 563 (see fig. 7) is a female symphysis with some of the left corpus and the dentition from the right i1 through the left m2, and the right p3. ARAVP1/740 (see fig. 7) is a ju venile mandible with most of the corpus and the right dp3m1 and the left dcm1. ARA VP1/548 (see fig. 7) is a right juvenile corpus with dp4 and m 1 in place, and the tips of the crowns of i1c just beginning to emerge from their crypts.

The symphysis slopes at an angle similar to that of Macaca fascicularis . This is more sloping than in many papionins when viewed in profile, but less so than the symphysis of Parapapio ado from Laetoli (Leakey and

ARAVP1/548 (reversed). 3rd row: ARAVP1/73, ARAVP1/563. 4th row: ARAVP1/133 left corpus (1349 is an old number), ARAVP1/1006 left corpus. Bottom row: ARAVP1/133 right corpus, ARAVP1/1006 right corpus.

Delson, 1987) and Kanapoi (Patterson, 1968), and considerably less so than in the papionin from Lothagam (Leakey et al., in press). The incisive alveolar plane is oriented nearly vertically, whereas it projects more anteriorly in the abovementioned taxa. The incisor row is thus nearly vertical in Pliopapio alemui , whereas the incisors of the others are more procumbent, with the central incisor projecting well beyond the lateral. The projecting alveolar process of P. ado produces a symphysis that is quite different in profile from that of Pl. alemui (see fig. 8). The symphysis is pierced by a median mental foramen. There appear to have been very faint, triangular mental ridges. The superior transverse tori in ARAVP1/73 and ARA VP1/133 extend posteriorly to the middle of P 4 in superior view. Both superior and inferior transverse tori are well developed.

The Middle Awash mandibles show only slight or no development of corpus fossae. Although there is some damage to the inferior margin in ARAVP6/933, it appears that the deepest point was relatively anterior, perhaps under p4, and that the inferior margin curved gently convex down. The inferior margin is thus anteriorly divergent. The oblique line emerges near the level of the mesial lophid of m3 or the distal lophid of m2. The extramolar sulcus is smooth and weakly developed. The gonial region is unexpanded. If present at all, the mylohyoid line is poorly developed.

Viewed superiorly, the tooth rows are nearly parallel along their lingual surfaces, from M3 to P3, with the canine slightly medial and the incisors curving sharply medially. In lateral view there is a normal curve of Spee (i.e., the tooth row is concave upward).

The ramus is well preserved only in ARA VP6/933. It is backtilted, although less so than in Papio but more so than in Macaca or Theropithecus (Theropithecus) . The coronoid process is even with or slightly higher than the condyle, from which it is separated by a shallow semicircular mandibular notch. There is a deep triangular fossa below the coronoid process on an otherwise relatively smooth lateral surface. The masseteric tuberosity is faint, and the whole area of its attachment is not heavily scarred.

Dentition. The incisors are fairly large relative to the molars, which is typical for most papionins. The I1 is broad, flaring, and spatulate in anterior view. The I2 is more asymmetrical and not as broad, with a small lateral tubercle. The lower incisors have straight mesial and distal borders in anterior view, so that they are less flaring than the uppers. The lateral border of the i2 is more laterally curved than that of the i1. As is typical of cercopithecines, they lack lingual enamel and the labial surface stands out, yielding a somewhat chisellike occlusal surface. The labial surface is often ‘‘squared’’ in occlusal view. The canines are typical of cercopithecoids, being highly sexually dimorphic and having a mesial groove on the uppers that extends onto the surface of the root.

The upper premolars are typical bicuspid papionin teeth. The p3 is a highly sexually dimorphic tooth. The paraconid is less well developed than in the colobine, and the male mesiobuccal flange is significantly longer than that of the females. The p4 develops a small mesiobuccal flange in some males (e.g., ARAVP6/933), has more of a talonid than the p3, and has a fairly high lingual notch.

The molars in general are highcrowned for a papionin, with relatively little flare, especially in comparison to the Kanapoi sample. Cusp relief above the lower lingual/upper buccal notch is high for a papionin, but lower than in colobines. Accessory cuspules are often present in the lingual notch. In the upper molars, the lingual cusps are elevated relative to the central basin and seem to be connected by continuous, welldeveloped postproto and prehypocristae. The mesial loph is wider than the distal. The M2 is often the largest of the upper molars. The lower molars have normal low relief and higher lingual notch. The buccal cusps tend to be fairly columnar, with the mesial and distal foveae being pinched, although not to the extent of those of Theropithecus . The floor of the median buccal notch seems to slope downward distally. On the m1–2, the distal cingula develop a very small hypoconulid 6–10% of thc time depending on scoring. In the m3, the hypoconulid is generally tightly pressed against the hypoconid, so that the distal buccal notch is very constricted compared to the mesial. Additionally, the distal buccal notch rarely preserves any ‘‘shelf’’ at the base.

The dI2 has a crown that is basically spatulate, low in height, broad, and angles mesially. The root is broad and labiolingually flattened. The dC is a mesiodistally elongate tooth, with a crown that is approximately triangular in labial view. The dc crown has a prominent central cusp that is labiolingually compressed and a crest that extends mesially from its apex. Distally there is a small accessory cuspule. In general, the deciduous premolars are similar to adult molars, but narrower, with more lateral flare, and loph(id)s that are more weakly developed than the adult teeth. In addition, the upper dPs have relatively larger mesial and distal foveae. The mesial fovea is particularly large and elongate on the dP3. The dp3 protolophid is much narrower than the hypolophid. There is also a welldeveloped preprotocristid, and what may be a paraconid, yielding a mesial fovea that is triangular in shape. The dp4 is more similar to an adult m1, but narrower with a relatively longer mesial fovea.

SUBFAMILY COLOBINAE JERDON, 1867

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.