Mystacina tuberculata, J. E. Gray, 1843

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6418929 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6606898 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/61143626-C158-FFE5-FF33-F68CFD65FC06 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Mystacina tuberculata |

| status |

|

Lesser New Zealand Short-tailed Bat

Mystacina tuberculata View in CoL

French: Petite Mystacine / German: Kleine Neuseelandfledermaus / Spanish: Murciélago neozelandés pequeno

Other common names: New Zealand Lesser Short-tailed Bat; Kauri Forest Lesser New Zealand Short-tailed Bat

(aupourica), Southern Lesser New Zealand Short-tailed Bat (tuberculata), Volcanic Plateau Lesser New Zealand Shorttailed Bat (rhyacobia)

Taxonomy. Mystacina tuberculata J. E. Gray View in CoL in Dieffenbach, 1843,

“ New Zealand.”

Three subspecies recognized based on morphological characteristics, but they are not well supported based on molecular evidence.

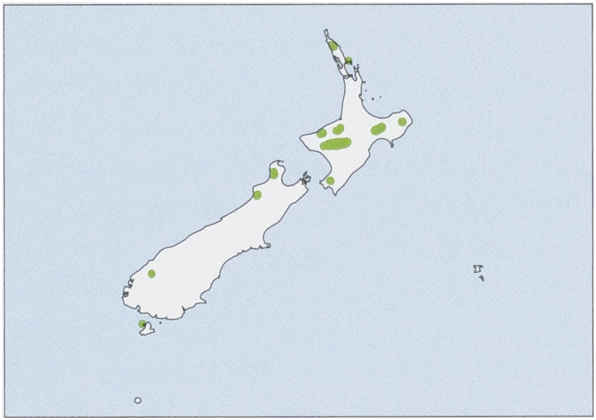

Subspecies and Distribution.

M.t.tuberculataJ.E.Gray,1843—SNorthIsland,SouthIsland,andCodfishI,NewZealand.

M.t.aupouricaHill&:Daniel,1985-NNorthIslandandoffshoreLittleBarrierI,NewZealand.

M. t. rhyacobia Hill & Daniel, 1985 — C North Island, NewZealand. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Total length with tail folded up 60-70 mm (plus ¢. 20 mm for uropatagium), tail c. 7 mm, ear 17-4-19-1 mm, hindfoot ¢c. 6 mm, forearm 36-9-46-9 mm; weight 10-22 g (pre-feeding). Body weight of female Lesser New Zealand Short-tailed Bats increases by ¢.35% during late pregnancy. Wingspans are 280-300 mm. Slight sexual dimorphism occurs in some populations, with females either heavier (4-3%) or heavier and possessing longer forearms (0-9%); some populations are monomorphic. Condylo-basal lengths are 17-3-19-1 mm. Pelage is brown (darker on dorsal surface than ventral) and covers body and head; ears, nose, wings, legs, andtail are bare. Skin is gray-brown. Nostrils are raised and cylindrical. Large basal talons on toes and thumb, reduced propatagium, and thickened proximal wing membranes aid in terrestrial locomotion. Males have permanently internal testes andlack bacula. Chromosomal complement has 2n = 36 and FN = 60.

Habitat. Large tracts of pristine, native forests from sealevel to high elevations. Native vegetationis required for roosting sites of Lesser New Zealand Short-tailed Bats, including large native trees for communal roosts. They will sometimes forage over grassland, open scrub, exotic pine plantations, rural gardens, andcliff faces and will fly across largetracts (c. 2 km) of grassland to reach foraging grounds. Historically, Lesser NewZealand Short-tailed Bats roosted in caves and burrows, but modern roosts have only been documented in trees and vegetation.

Food and Feeding. Lesser New Zealand Short-tailed Bats eat arthropods, fruit, nectar, and pollen, with a flexible diet that is largely dictated bylocal and seasonal food availabilities. There is some evidence of feeding on ferns and fungi. Arthropods are pursued via aerial-hawking, surface gleaning, andterrestrial locomotion on the forest floor. Lesser New Zealand Short-tailed Bats have several adaptations to nectarivory, including a gap in front teeth to extend papillated tongue. They are important pollinators and seed dispersers of a numberofnative plant species, including the endemic native woodrose Dactylanthus taylorii ( Balanophoraceae ).

Breeding. Male Lesser New Zealand Short-tailed Bats pursuea lek-breeding strategy when population densities are high, vocalizing nightly from singing roosts clustered around communal roosts used by females. Singing begins as early as September, peaking in January-February. Twoto five males share somesinging roosts in apparent longterm coalitions. Song output scales negatively with male size, and “timeshare” males are larger than solitary males. Smaller males appear to have higher paternity success. Females mate with males within their singing roosts, and vaginal plugs are formed during mating. Following mating, there is a delayin fertilization, implantation, or development. Females are monoestrous, giving birth once per year in December—January. Births are usually synchronized, taking place within a week ofeach other, and usually occurin a single communal roost selected as the maternity roost by the population (or young are carried to the maternity roost by the motherif born elsewhere). Females generally give birth to one young, although twins are possible. Young are hairless and c.5b g when born and arefully furred and volant by four weeks old.

Activity patterns. Lesser New Zealand Short-tailed Bats are active nightly 21-150 minutes after sunset, with activitylevels positively correlated with temperature and rainfall in winter, but uncorrelated with temperature in summer. Activity can be punctuated by periods of night roosting, depending on the population and moon phase. Individuals usually return to communal roosts within 30 minutes of the beginning of twilight. Lesser New Zealand Short-tailed Bats might use torpor daily and seasonally depending on food availabilities and daytime temperatures. They are generally active nightly even in subzero temperatures in winter. Wing morphology suggests high maneuverability and facilitates flying in cluttered environments, gleaning prey from surfaces, and ability to takeoff from the ground without sacrificing flight speed, estimated as high as 60 km /h.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Lesser New Zealand Shorttailed Bat is oneofthe most gregarious tree-roosting bats in the world, with communal roost trees containing thousands ofindividuals. Communal roosts are largest in spring and summer, and most individuals roosting alone in winter. Populations generally inhabit several communal roosts within their home range simultaneously, although coordinatedroost switching does occur, with all individuals leaving a single communal roost and inhabiting a new one overnight. Generally, individuals switch communal roosts every few days, although some communal roosts can be used continuously for months at a time. Many individuals also have solitary roosts that can be inhabited periodically year-round. Home range sizes vary among individuals and populations and are 0-05-62-2 km?*. Individuals can travel more than 10 km to reach nightly foraging grounds.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. Subspecies aupourica, rhyacobia, and tuberculata are listed as “Nationally Vulnerable,” “Declining,” and “Recovering,” respectively, by the New Zealand Threat Classification System. It is estimated that there are currently fewer than 50,000 Lesser New Zealand Short-tailed Bats in 13 known populations. Modern threats are competition and predation from introduced pests such as rats, feral cats, possums, and wasps. Pest management programs appear to be essential for the recovery and continued survival of the Lesser New Zealand Short-tailed Bat.

Bibliography. Arkins et al. (1999), Bickham et al. (1980), Borkin & Parsons (2010a), Carter & Riskin (2006), Christie (2006), Christie & Simpson (2006), Czenze et al. (2017a, 2017b), Daniel (1976, 1979, 1990b), Ecroyd (1996), Gray (1843b), Hill & Daniel (1985), Jones et al. (2003), Kunz & Lumsden (2003), Lloyd (2001, 2003, 2005a), O'Donnell (2008b), O'Donnell, Borkin et al. (2018), O'Donnell, Christie et al. (1999), Peterson et al. (2006), Sedgeley (2001a, 2003, 2006), Toth & Parsons (2018), Toth, Cummings et al. (2015), Toth, Dennis et al. (2015), Toth, Santure et al. (2018), Winnington (1999).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.