Panthera pardus (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6376899 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6772612 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/5923B274-4667-C80B-E2F9-C92EF6F09F23 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Panthera pardus |

| status |

|

5. View On

Leopard

French: Léopard / German: Leopard / Spanish: Leopardo

[.

Taxonomy. Felis pardus Linnaeus, 1758 ,

Egypt.

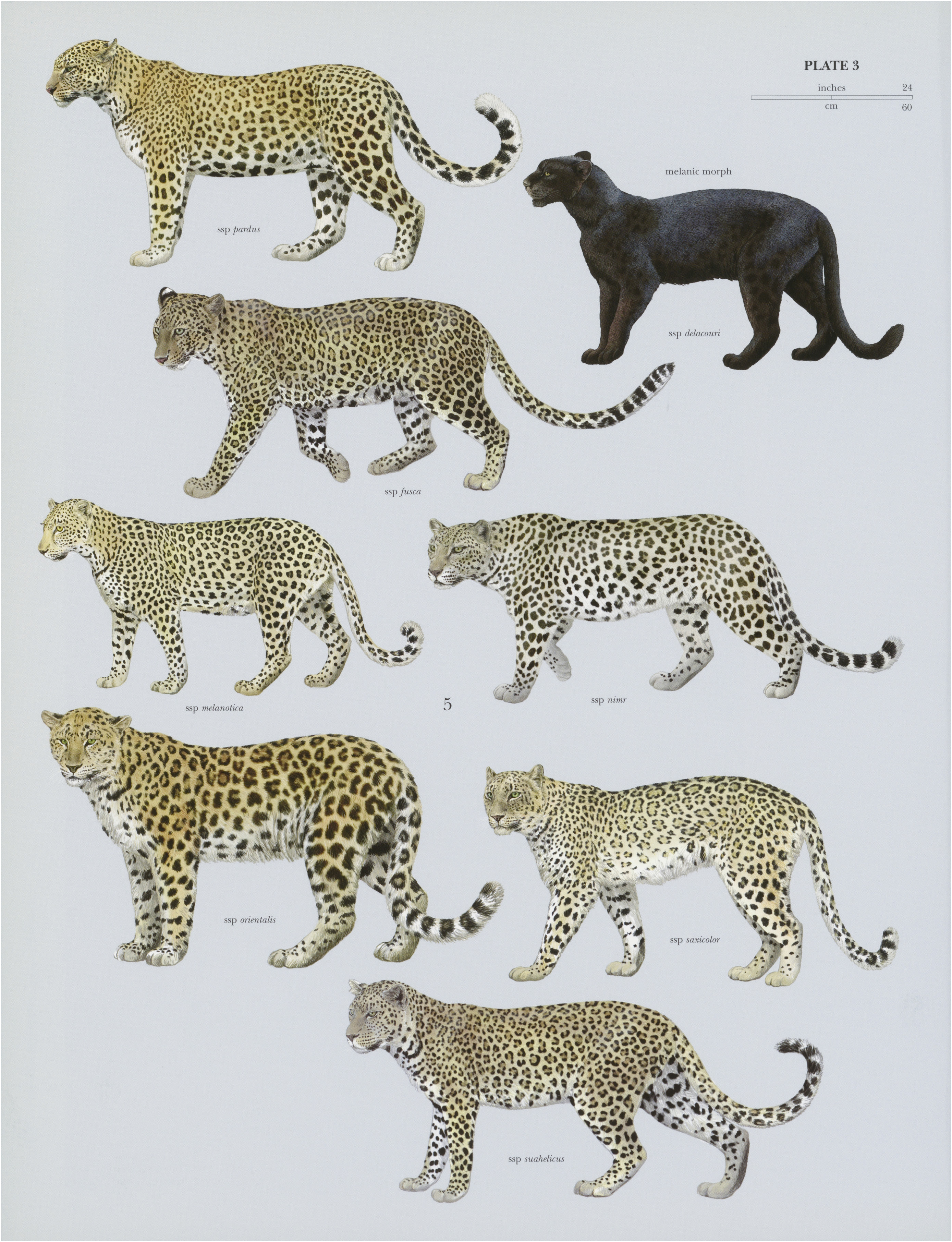

Recent morphological and genetic analyses suggests subsuming all African races into pardus , all populations on the Indian subcontinent into fusca, and all Central Asian races into saxicolor. Twenty-four subspecies are currently recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

P. p. pardus Linnaeus, 1758 — Sudan and NE Zaire.

P. p. adersi Pocock, 1932 — Zanzibar I (could be extinct).

P. p. adusta Pocock, 1927 — Ethiopian highlands.

P. p. ciscaucasicus Satunin, 1914 — Caucasus mountains.

P. p. dathei Zukowsky, 1959 — S and C Iran (of dubious validity).

P. p. delacouri Pocock, 1930 — S China to Malay Peninsula.

P. p. fusca Meyer, 1794 — Indian subcontinent.

P. p. japonensis Gray, 1862 — NC China.

P. p. jarvisi Pocock, 1932 — Sinai Peninsula.

P. p. kotiya Deraniyagala, 1949 — Sri Lanka.

P. p. leopardus Schreber, 1777 — Rain forests of W and C Africa.

P. p. melanotica Gunther, 1775 — S Africa.

P. p. melas Cuvier, 1809 — Java.

P. p. nanopardus Thomas, 1904 — Somali arid zone.

P. p. nimr Hemprich & Ehrenberg, 1833 —S Israel to Arabian peninsula.

P. p. orientalis Schlegel, 1857 — Russian Far East, Korea, and NE China.

P. p. panthera Schreber, 1777 — N Africa.

P. p. pernigra Gray, 1863 — Kashmir through Nepal to SW Xizang and Sichuan.

P. p. reichenow: Cabrera, 1918 — Savannas of Cameroon.

P. p. ruwenzori Camerano, 1906 — Ruwenzori and Virunga mountains of Zaire, Rwanda, and Burundi.

P. p. saxicolor Pocock, 1927 — N Iran and S Turkmenistan E to Afghanistan.

P. p. sindica Pocock, 1930 — SE Afghanistan through W and S Pakistan.

P. p. suahelicus Neumann, 1900 — E Africa, from Kenya S to Mozambique.

P. p. tulliana Valenciennes, 1856 — Turkey. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 92-190 cm,tail 64-99 cm; weight 21-71 kg. Adult males are larger than adult females. There is considerable regional variation in body size and weight. Adult Leopards from Cape Province, South Africa, are among the smallest, with mean weight of males at 30-9 kg and females at 21-2 kg. However, adult males weighing 50 to 60 kg are reported from many regions of the Leopard’s range. Background coat color varies from bright golden yellow to a pale yellow to rusty-reddish yellow, depending on region. Underparts are white. Hair is short and coarse in cats from warmer climates, but winter coat of Leopards from Russian Far Eastis soft, long (3-7 cm), and dense. Black spots are found on head, neck, shoulders, limbs, and hindquarters. Black spots form broken circles or rosettes on sides and back. The rosettes typically lack a black spot in center, as seen on the Jaguar. Melanistic Leopards are known from several regions of Africa, but there is a much higher frequency of black Leopards from Thailand, Malaysia, and Java. Tail is relatively long, more than half the head-body length, and covered with dark spots, bands, and blobs; tip is black above and white below. Backs of ears are white on upper half and dark below. Pattern of markings on coat, head, and muzzle are individually unique.

Habitat. As might be predicted from its broad geographic distribution, Leopards are able to live in almost every type of habitat. In sub-Saharan Africa the cats are found in all habitats that have an annual rainfall above 50 mm. They are also found in true deserts, but only where river courses extend into this otherwise inhospitable habitat. In the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park, South Africa, Leopards inhabit arid, open-dune sandveld with scattered shrubs and trees. They escape the intense midday heat by sheltering in porcupine or aardvark burrows. Tracking studies in the Kalahari have shown that Leopards can survive without drinking for as long as ten days. In other hot, dry deserts such as the Namib, Sahara, Sinai, and Arabian, Leopards also use caves, burrows, or the shade of dense vegetation to survive daytime temperatures that may reach 70°C. In other parts of Africa Leopards occur in the wetter habitats, including savannas, acacia grasslands, evergreen and deciduous forests, and scrub woodlands. They also occur in the rain forest habitats of Central and West Africa, where annual rainfall typically exceeds 1500 mm. Leopards are common throughout the Indian subcontinent, from the moist deciduous, teak, and shola forests of the Western Ghats to the dry, deciduous, bamboo, and mixed forests of the rugged tableland in central India. In the north they live in sal forest and the tall grasslands on the outwash plains of the Himalaya as well as in the mountainous terrain of Pakistan and Kashmir to 5200 m. In Myanmar, Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, and Java the cats are found in dense, primary rain forest and a variety of other forest types. In the Russian Far East Leopards inhabit mountainous forested regions. They prefer broken topography with Korean pine and second growth oak forest. In this area, a key limiting factor is snow depth. The cats prefer habitats where the average long-term snow cover does not exceed 15 cm. Whatever type of habitat they live in, Leopards are often able to persist in close proximity to people, as long as they are not persecuted and have access to secure den sites. Remarkably, three Leopards were discovered living in an abandoned engine at the railroad station in Kampala, Uganda. In India it is not uncommon to read newspaper accounts ofvillagers finding leopards hiding in sheds and outbuildings.

Food and Feeding. Leopards are adaptable generalists, able to survive on an extraordinary variety of large or small prey. In many areas the cat’s diet consists largely of small to medium-sized mammals (5-45 kg), but even ungulates weighing two to three times the cat’s body weight are occasionally taken. Leopards can also survive on extremely small prey, an ability that allows them to live in areas from which larger prey has long since been extirpated. The cat has a truly catholic diet, taking an incredible variety of different prey sizes and types. At least 92 prey species are known from the Leopard’s diet in sub-Saharan Africa. Where Leopards live near villages their diet often includes dogs, cats, sheep, goats, calves, and pigs. A large number of sheep or goats can be killed in a single incident when a Leopard findsitself in a pen with a frightened flock. The Leopard’s fondness for dogs is well known and there are many accounts of family pets or village dogs disappearing in the night. Food habit studies from different parts of the Leopard’s geographic distribution illustrates the cat’s adaptability. In the Serengeti, Impala ( Aepyceros melampus) and Thompson's Gazelles ( Eudorcas thomsonii) are the principal prey, but other bovids (Bushbuck Tragelaphus scriptus, Common Reedbuck Redunca redunca, Blue Wildebeest Connochaetes taurinus, Grant's Gazelle Nanger granti, Topi Damaliscus korrigum, Hartebeest Alcelaphus buselaphus) are also taken. Less frequently taken prey incude Common Warthog (Phacochoerus africanus), Burchell’s Zebra (Equus burchellir), hyrax, spring hare, baboons, birds, and small carnivores. Impala are also the dominant prey (78% ofkills) in Kruger National Park, although the cats occasionally prey on other bovids (Bushbuck, Reedbuck, Blue Wildebeest, Waterbuck Kobus ellipsiprymnus, Kudu Tragelaphus strepisceros, Nyala 1. angasii, Common Tsessebe Damaliscus lunatus, Common Eland Tawrotragus oryx, Sable Antelope Hippotragus niger, and African Buffalo Syncerus caffer). In the Kalahari, Springbok ( Antidorcas marsupialis) is the most important prey (65% of kills), but duikers, Steenbok ( Raphicerus campestris), Blue Wildebeest, Hartebeest, and Gemsbok ( Oryx gazella) are also taken. Incidental prey included small carnivores, birds, rodents, Cheetahs, Aardwolves, and Aardvarks. Duikers were the most important prey in north-east Namibia; Steenbok ranked second. A variety of other carnivorous animals were also killed, including Aardwolf, Cheetah, Genet, Bat-eared Fox, Wildcat, and python. A major difference in the diets of African Leopardsis that cats from tropical rain forests take signifi cantly more primates. In the Ituri Forest, Zaire, primates comprised 25% of prey items in Leopard scats. Of 13 species of diurnal anthropoid primates in the area, remains of at least eleven species were identified in scats. Arboreal guenons, mangabeys, and colobines ( Cercopithecidae ) were taken in proportion to their abundance, but predation on ['Hoest’s Monkey ( Cercopithecus lhoesti), a terrestrial species, was much greater than expected based on their availability. Despite the increased percentage of primates in the diets of Ituri Forest Leopards, their principal prey was medium-sized ungulates. In the Tai National Park, Ivory Coast, primate remains were found in 25% of scats; Leopards killed at least eight species of primate (Ceropithecidae, Lorisidae ). Duikers were the dominant prey in the park, but bushpigs (Potamochoerus), Forest Hogs (Hylochoerus meinerizhageni), porcupines, pangolins, hyrax, Water Chevrotain (Hyemoschus aquaticus), and rodents were also taken. Leopards in Asia prey largely on small to mediumsized ungulates. In Nagarhole National Park, India, Chital, muntjac, and Sambar ( Cervidae ) were found in 656% of scats; the remains of Gaur and Four-horned Antelope ( Tetracerus quadricornis), Wild Boar, and chevrotain were found in 19% of scats. Incidental prey included primates, hares, porcupines, and Dhole. The small (15-20 kg) muntjac was the dominant prey (43%) in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand. Primates ranked second (11%) in scats, followed by porcupines (10%). Less frequently occurring prey included Sambar, Wild Boars, Hog Badgers, pangolins, rodents, birds, lizards, and crabs. In Wolong Reserve, China, Tufted Deer ( Elaphodus cephalophus) are the principal prey (41%). Musk deer, Sambar, Wild Boar, and several species of bovids (Serow Capricornis, Takin Budorcas taxicolor, Goral Naemorhedus ) were taken occasionally. Surprisingly, rodents were the second most frequently occurring prey (17%) in scats. The remains of a Red Panda and a Giant Panda were each found in a scat. In the Russian Far East more than half of the Leopard's diet consists of Siberian Roe Deer. Secondary prey include Siberian Musk Deer, Sika Deer, Wild Boar, hare, badger, Raccoon Dog, and pheasants. Leopards locate their prey primarily by sight and sound, and they spend considerable time looking and listening for prey as they walk slowly about their home ranges. Having detected an animal, the Leopard will stalk it, preferring to get as close as possible before launching an attack. Alternatively, it will lie in ambush, waiting for the prey to come close enough to attack. Adult prey are rarely pursued, although young, inexperienced animals are sometimes chased for considerable distances. Most hunting is done at night, taking advantage of the cover of darkness, and what little information is available suggests hunting success is higher at night. Leopards occasionally hunt during the daytime, but typically only in areas with dense cover. Few people have actually observed Leopards trying to capture an animal. In Kruger National Park, Leopards were unsuccessful on thirteen daytime attempts, but two attempts at night were both successful. In the Serengeti National Park, only one of nine and three of sixty-four daytime attempts to capture prey were successful. Like otherlarge felids, Leopards commonly kill large prey with a bite to the throat. Small prey are usually dispatched with a bite to the nape or back of the head. Leopards go to great lengths to avoid losing their kills to scavengers and larger predators. They will drag carcasses hundreds of meters to get to areas with dense cover or to cache kills in trees. Hauling a carcass into a tree involves a great feat of strength. One Leopard managed to haul a 125 kg giraffe calf up into a tree to a height of 5-7 m. The habit of caching kills in trees appears to be more common in Africa, where large carnivores such as Lions and hyenas will quickly steal kills from the smaller and less powerful leopard. In the Serengeti, Leopard kills stored in trees lasted about four times longer than similarsized kills stored on the ground. How often a Leopard kills depends on variables such as size of prey, seasonal changes in cover, individual differencesin levels of experience, and reproductive constraints. Leopards in Kruger National Park killed on average about one Impala per week. The longest interval between kills of large prey was 19 days. In the Serengeti, where Thompson's Gazelles were the principal prey, Leopards made a kill about every five to six days. A female Leopard in South Africa’s Londolozi Game Reserve was seen with 28 kills weighing more than 10 kg in 330 days, or about one kill every 11-8 days. The kill rates in Kruger were slightly higher in the wet season than in the dry season, which was thought to be related to the increased density of stalking cover following the onset of the rains. Males in Kruger killed a large prey animal about once every 7-2 days compared to once every 7-5 days for females without young. In the Kalahari Desert, male Leopards made a kill about every three days, compared to once every 1-5 days for females with cubs. As the interval between kills got longer, Leopards in the Kalahari increased the distances they traveled each day to increase contact rates with prey. Females in north-east Namibia without young made a kill about once every 5-5-6 days, whereas females with dependent young made a kill every 3-9—4-4 days. Although the kill rate was not much higher for females with young, they did kill larger prey, resulting in a greater per capita food intake. The amount of meat consumed varies, depending on the size of the prey, how much meat is lost to scavengers, and the percentage of carcass that is inedible. Estimates of consumption vary from 4.7-3. 1 kg /day for adult male Leopards in Kruger to 2-9 kg/day for adult females in the same area. Leopards in captivity are maintained on about 1-2 to 2-6 kg/ day, but they surely have less caloric demands than animals in the wild.

Activity patterns. In most areas where Leopards have been studied the cats are largely nocturnal. In Sri Lanka, where they are the only large carnivore, they are commonly sighted in open habitats during the daytime, suggesting that their activity patterns are influenced by the presence of other large carnivores.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Few studies have actually monitored the movements of Leopards, but in the interior dune areas of the Kalahari Desert, males traveled an average of 14-3 km/day. Females with cubs averaged 13-4 km/day. The maximum distances traveled by males were 27-3 km per day (non-mating period) and 33 km /day (mating period). The maximum distance traveled by a female with cubs was 24-6 km/day. In more productive habitats the distances traveled per day are considerably less. Leopards in Tsavo National Park averaged 2-6 km/day (range 0-9-4-2 km/day) and in the South-west Cape Province the distances traveled by three males were usually less than 3 km /day. There is great variation in home range sizes of Leopards. In high-quality habitats females can meet their needs within relatively small areas. The home range of an adult female living on the prey-rich floodplain of Nepal's Chitwan National Park measured only 8 km? while the ranges of two females living along the edge of the park were 6-13 km*. In Kruger National Park, females living in riparian habitats had similarly small ranges, averaging about 14-8 km*. The ranges of resident females on a livestock ranch in Kenya were about 14 km ®. Male ranges in these areas were two to three times larger than female ranges. The year-round home ranges of two female Leopards in the Russian Far East were 33 and 62 km?*; a male’s range was at least 280 km?. In areas of extremely low prey density, female ranges of 128 to 487 km? have been reported. The home range of a male in the interior dune area of the Kalahari Desert was estimated at 800 km ®. Leopardsare solitary, and outside of mating the only long-term association is a female and her young. Each male’s range usually overlaps the range of one or more adult females. The larger male ranges will often include areas ofless productive habitats; females compete for the best areas, because habitats with abundant resources enhance their reproductive success. In some parts of Africa, long-term sightings of individually-recognizable Leopards suggest that females are philopatric, in that daughters tend to establish ranges next to their mothers’. Density estimates of leopards vary from a low of 0-6/ 100 km ® in the interior dune area of the Kalahari Desert to 30-3/ 100 km? in the riparian forest areas of Kruger National Park. Estimates of 3-5 to 12:5/ 100 km? appear to be more common.

Breeding. Zoo records show that females may come into estrus at any time of the year and they remain in heat for one to two weeks. In the wild mating associations are brief, lasting only one or two days. Young are born after a gestation period of about 96 days. Litter size varies from 1-3, but there are records of females having as many as six cubs. Most litters consist of two young. Females use caves, rocky outcrops, abandoned burrows, or dense thickets for birth dens. For the first few days after the cubs are born the mother spends practically all her time at the den, resting and nursing the young. Later, when she leaves to hunt, she may be away from the den site for 24-36 hours. Leopard cubs are very vulnerable to predation during this time. Most cub mortality occurs during the first few months of life. Older cubs are also left unattended for long periods of time. Studies in north-east Namibia found that three-month-old cubs were left for periods of one to seven days while their mother hunted. Young generally begin traveling with their mother when they are about three months old and weigh 3-4 kg. There are records of five-month old cubs killing hares and other small animals, but more commonly this coincides with the appearance of their permanent canines at about 7-8 months of age. By the time Leopards are 12-18 months of age, the young are usually independent of their mother, but the timing of dispersal varies from 15 to 36 months. Sexual maturity is attained by two to three years of age.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Four subspecies (Arabian, Amur, North African, and Anatolian Leopard) classified as Critically Endangered on The IUCN Red List. Four subspecies (Caucasus, Sri Lankan, North Chinese, and Javan Leopard) listed as Endangered. Otherwise classified as Near Threatened on The IUCN Red List. The Leopard is in the odd position of being endangered in some parts of its range and a pest in others. Leopards clearly have the ability to survive near humans. They can feed on almost any type of prey and do not have highly specific habitat requirements. However, they are vulnerable to persecution. The greatest threat to the Leopard's continued survival is the loss of habitat and wild prey as livestock activities expand.

Bibliography. Arivazhagan et al. (2007), Bailey (1993), Bertram (1982), Bothma & LeRiche (1984, 1986, 1989, 1990), Cat News (2006), Desai (1975), Eaton (1977), Eisenberg & Lockhart (1972), Grassman (1998b), Grobler & Wilson (1972), Hamilton (1976), Hart et al. (1996), Hayward etal. (2006), Heptner & Sludskii (1992b), Hes (1991), Hoppe-Dominik (1984), llany (1981, 1990), Jenny (1996), Johnson et al. (1993), Karanth & Sunquist (1995, 2000), Khorozkyan & Malkhasyan (2002), Le Roux & Skinner (1989), Martin & Meulenar (1988), McDougal (1988), Mendelssohn (1989), Mills (1984b), Miquelle et al. (1996), Miththapala, Seidensticker & O'Brien. (1996), Miththapala, Seidensticker, Phillips et al. (1989), Mizutani & Jewell (1998), Muckenhirn & Eisenberg (1973), Norton & Henley (1987), Norton & Lawson (1985), Nowell & Jackson (1996), Odden & Wegge (2005, In press), Pienaar (1969), Pocock (1932a), Rabinowitz (1989), Sadleir (1966), Schaller (1967), Scott (1985), Seidensticker (1976a, 1977), Seidensticker et al. (1990), de Silva & Jayaratne (1994), Smith (1977), Stander et al. (1997), Stuart & Stuart (1991), Sunquist (1983), Sunquist & Sunquist (2002), Turnbull-Kemp (1967), Wilson (1977).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.