Cercomacroides, Tello & Raposo & Bates & Bravo & Cadena & Maldonado-Coelho, 2014

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1111/zoj.12116 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F7A915-3256-BA07-D48D-FDB59B9FFB81 |

|

treatment provided by |

Carolina |

|

scientific name |

Cercomacroides |

| status |

|

AND CERCOMACROIDES

Posterior rate estimates (parameter ‘meanRate’ in BEAST) ranged from 0.30 to 0.42% s s−1 Mya –1 for FIB5, 1.92 to 2.16% for CYTB, 1.82 to 2.40% for ND3, and 2.24 to 2.86% for ND2. According to this tree ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ), the age of the roots of Cercomacra and Cercomacroides clades ranged from the late Miocene through the early Pliocene between 9.3 and 4.2 Mya [ Cercomacra , mean = 6.7 Mya (9.3– 4.5 Mya); Cercomacroides , mean = 6.2 Mya (8.6– 4.2 Mya)]. Subsequent major splits within the Cercomacra and Cercomacroides clades all are estimated to have occurred between the Late Miocene and Late Pleistocene (9.3–0.3 Mya within Cercomacra ; and 8.6–3.3 Mya within Cercomacroides ). The separation of Cercomacroides from Sciaphylax was estimated to have occurred c. 9.6 Mya (13.2–6.4 Mya), and this latter clade separated from the Hypocnemis – Drymophila clade c. 11.0 Mya (15.0–7.5 Mya). Finally, the Cercomacroides – Sciaphylax – Hypocnemis – Drymophila clade separated from Cercomacra at approximately 11.6 Mya (15.9–7.9 Mya).

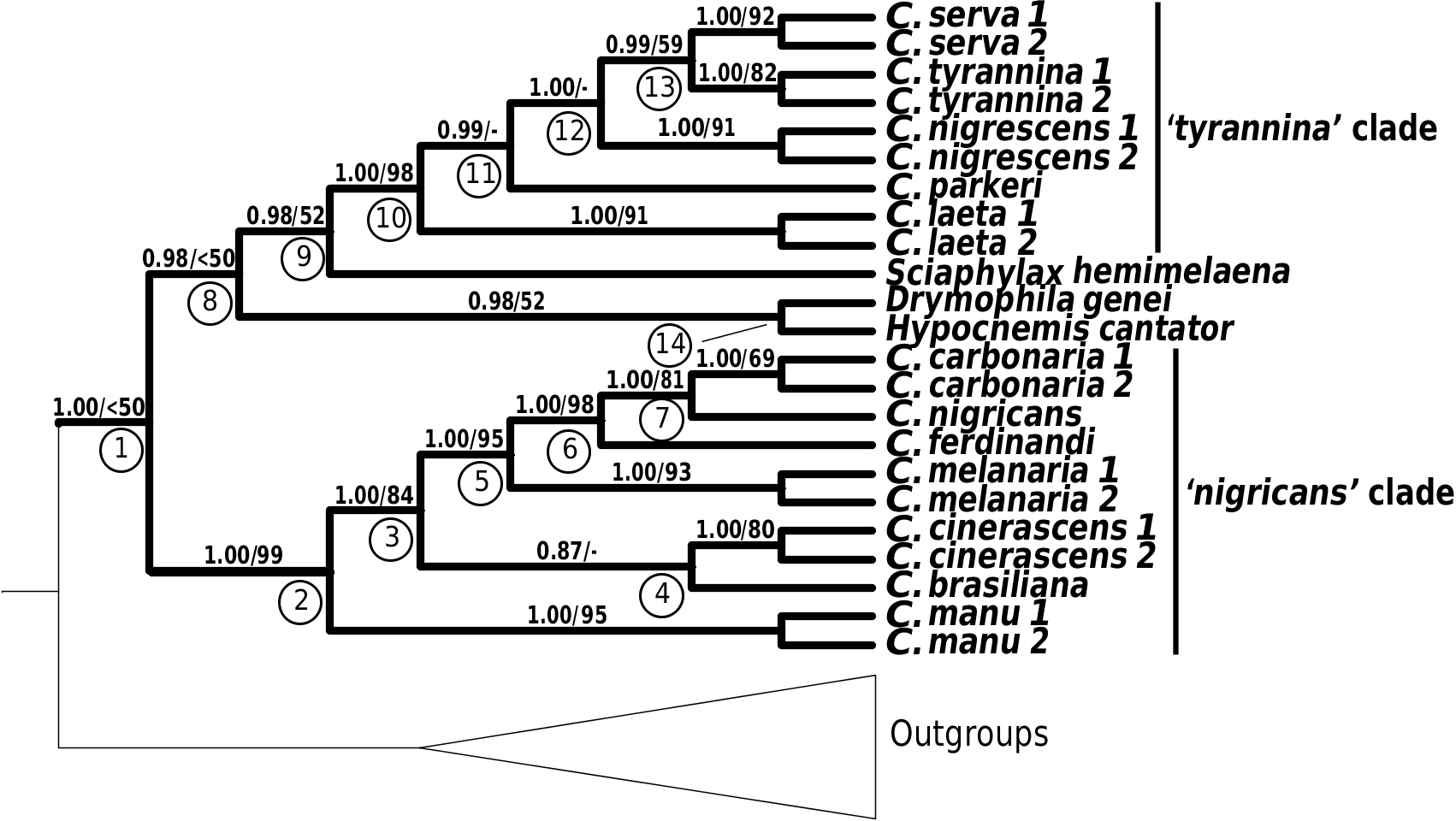

The ancestral Cercomacra lineage split from its most recent common ancestor in the mid to late Miocene (see above). Cercomacra manu , the taxon diverging first from the rest of the genus, split in the late Miocene to early Pliocene between 9.3 and 4.5 Mya. The phylogenetic position of brasiliana and cinerascens is not yet resolved. Cercomacra brasiliana is either sister to cinerascens ( Figs 3 View Figure 3 , 4B View Figure 4 ) or sister to the cinerascens –circum-Amazonian clade ( melanaria , ferdinandi , carbonaria , and nigricans ) ( Fig. 4A View Figure 4 ). Alternatively, it may be sister to the circum- Amazonian clade (although this relationship was not recovered in any of the analyses). Internal branches separating these three major clades are short and divergence of all three occurred within 1 Mya ( Figs 4A View Figure 4 , 7 View Figure 7 ). The mitochondrial tree suggests that brasiliana is sister to the cinerascens –circum- Amazonian clade, and that divergence occurred in the late Miocene to early Pliocene between 8.0 and 3.9 Mya. The mitochondrial topology shows that cinerascens is sister to the circum-Amazonian clade, diverging in the late Miocene to early Pliocene between 7.6 and 3.7 Mya. Within the circum- Amazonian clade, the split of melanaria from the rest of the taxa took place between 6.0 and 2.8 Mya. Subsequent splits in Cercomacra took place in the Pleistocene and included the separation of ferdinandi from the carbonaria – nigricans clade between 0.9 and 2.1 Mya, and the separation of carbonaria and nigricans between 0.8 and 0.3 Mya.

The ancestral Cercomacroides lineage split from its most recent common ancestor in the middle to late Miocene between 13.2 and 6.4 Mya. The lack of resolution of the internal nodes in the Cercomacroides tree due to data incongruence prevents us from determining the order in which internal splits took place. However, the mitochondrial topology suggests that the earliest split took place sometime in the late Miocene to early Pliocene between 8.6 and 4.2 Mya, and involved the basal divergence between nigrescens and the laeta – tyrannina – parkeri – serva clade. The order of splits that separated these four taxa is unknown, but based on the mitochondrial tree estimates, we can suggest that they took place not far from each other sometime between 6.8 and 3.3 Mya ( Fig. 7 View Figure 7 ).

Cercomacra View in CoL and Cercomacroides constitute two independent lineages of similar age distributed in several major areas of endemism (Table S4), whose relationships can provide important insights on the biogeography of the Neotropical lowlands. Both genera originated sometime between the late Miocene and early Pliocene. This range of time, particularly between 3 and 7 Mya, coincides with molecular estimates of the time of origin of several Neotropical avian genera (e.g. Lovette, 2004; Pereira & Baker, 2004; Barker, 2007; Miller et al., 2008; Ribas, Miyaki & Cracraft, 2009; Antonelli et al., 2010; Patel et al., 2011). Diversification in the late Miocene to early Pliocene coincides with a time period of dynamic geomorphological activity in the region ( Antonelli et al., 2010; Hoorn et al., 2010a; Wesselingh et al., 2010). During this period, the completion of presentday patterns of river systems and drainage divides in South America began to be achieved ( Campbell, Frailey & Romero-Pittman, 2006; Figueiredo et al., 2009; Hoorn et al., 2010b; Latrubesse et al., 2010). A combination of tectonics (Andean uplift) and sea transgressions, due to sea-level rise, led to the formation of structural arches, palaeorivers, and ancient lakes that may have contributed to diversification of biota ( Lundberg et al., 1998; Hoorn et al., 2010a; Wanderley-Filho et al., 2010). Diversification during the late Pliocene coincides with a time of strong global cooling and the formation of the first glacial period at the end of the Pliocene ( van der Hammen & Hooghiemstra, 2000), with subsequent effects on the vegetation cover, structure, and species composition of the region ( Colinvaux et al., 1996; Haffer, 1997, Colinvaux & De Oliveira, 2001; Haffer & Prance, 2001; Behling, Bush & Hooghiemstra, 2010). This also coincides with the presence of an extensive wetland system occupying the western Amazonian basin ( Klammer, 1984; Frailey, 1988; Marroig & Cerqueira, 1997; Hoorn et al., 2010b). The palaeogeographical conditions at that time (arches, river basins, etc.) that start forming at the late Miocene, together with climate fluctuations that characterized the late Pliocene to late Pleistocene, may have contributed to the origination of current Neotropical avian diversity ( Haffer, 1997; Aleixo & Rossetti, 2007; Antonelli et al., 2010).

All these factors may have played some role in the diversification of Cercomacra View in CoL and Cercomacroides lineages. Today, the distributions of members of these two lineages present an interesting contrast to the majority of currently documented biogeographical patterns for Amazonian birds. These birds exhibit a great degree of range overlap that exists within related lineages of different ages. Cercomacra View in CoL includes divergent overlapping Amazonian taxa, including the more restricted manu View in CoL and the widespread Amazonian cinerascens View in CoL along with the circum-Amazonian lineage, one of which ( carbonaria View in CoL ) has a distribution completely within the range of cinerascens View in CoL ( Fig. 1 View Figure 1 ). Ecological differences between these species are significant (e.g. manu View in CoL is a bamboo specialist, carbonaria View in CoL a gallery forest species and cinerascens View in CoL a mid-canopy, vine tangle specialist). The ecological differences between the broadly overlapping members of Cercomacroides ( serva and nigrescens ; laeta and tyrannina ) are less obvious and offer an interesting system to investigate the co-occurrence of comparatively young and ecologically similar lineages in Amazonia View in CoL .

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Cercomacroides

| Tello, Jose G., Raposo, Marcos, Bates, John M., Bravo, Gustavo A., Cadena, Carlos Daniel & Maldonado-Coelho, Marcos 2014 |

Cercomacroides

| Tello & Raposo & Bates & Bravo & Cadena & Maldonado-Coelho 2014 |

Cercomacroides

| Tello & Raposo & Bates & Bravo & Cadena & Maldonado-Coelho 2014 |

Cercomacroides

| Tello & Raposo & Bates & Bravo & Cadena & Maldonado-Coelho 2014 |

serva

| Tello & Raposo & Bates & Bravo & Cadena & Maldonado-Coelho 2014 |

nigrescens

| Tello & Raposo & Bates & Bravo & Cadena & Maldonado-Coelho 2014 |

laeta

| Tello & Raposo & Bates & Bravo & Cadena & Maldonado-Coelho 2014 |

tyrannina

| Tello & Raposo & Bates & Bravo & Cadena & Maldonado-Coelho 2014 |

Cercomacra

| SCLATER 1858 |

Cercomacra

| SCLATER 1858 |

Cercomacra

| SCLATER 1858 |