Pereute cheops Staudinger, 1884

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.1080/00222931003633227 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F66F7D-AA28-BC3D-FE0A-FC0FFE0DFC37 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Pereute cheops Staudinger, 1884 |

| status |

|

Pereute cheops Staudinger, 1884 View in CoL

This species ( Figure 8 View Figures 4–13 ) is endemic to southern Costa Rica and western Panama of Central America ( D’Abrera 1981; Lamas 2004) where it appears to be restricted to montane rain shadow valleys on the Pacific slope of Cordillera de Talamanca ( DeVries 1987). DeVries (1986, 1987) listed the larval food plant as Antidaphne viscoidea based on an ovipositing female, although the immature stages were not reared on this plant. He also provided brief notes on the egg and first-instar larva: the eggs were laid in a single cluster and were described as bright yellow; the larvae were reported as being slightly hairy, with the head capsule black and body translucent green. The final-instar larva and pupa have not previously been reported. The following observations on the life history of P. cheops were based on material reared from Costa Rica at Copey ( 1850 m a.s.l.) on the Pacific slope of Cordillera de Talamanca.

Immature stages

Fifth-instar larva

See Figures 89–91 View Figures 81–91 ; 39 View Figures 34–44 mm long, head capsule 3.5 mm wide ( n = 15); head black, with long yellow setae; body maroon to chocolate-brown, with a darker middorsal line, numerous small yellow panicula from which arise long yellow setae (up to 3.3 mm long), and numerous very short brown secondary setae; prothorax with a broad, rectangular-shaped black dorsal plate bearing numerous long yellow setae; posterior end of metathorax with a single transverse row of long yellow setae; anterior end of abdominal segment 1 with an obscure yellow subdorsal patch bearing a few long setae (approx. 11); abdominal segment 10 with a black dorsal plate bearing a few short setae; spiracles black.

Pupa

See Figures 222, 223 View Figures 218–235 ; 26 View Figures 24–33 mm long, 7 mm wide ( n = 16); dark shiny brown, tinged reddish on abdomen; head with a short prominent anterior projection, and a small subdorsal protuberance posteriorly; anterior projection stout, upturned, bifurcated apically and T-shaped; prothorax with a pronounced longitudinal dorsal ridge; mesothorax with a pronounced longitudinal dorsal ridge, a double rounded lateral protuberance at base of fore wing, and a broad lateral ridge posterior to lateral protuberance; metathorax with a shallow longitudinal dorsal ridge; abdominal segment 1 with a very small dorsolateral protuberance; abdominal segments 2 and 3 each with a dorsolateral protuberance; abdominal segment 4 with a weak dorsolateral protuberance; abdominal segment 2 with a middorsal ridge; abdominal segments 3–8 each with a prominent middorsal projection, terminating in a tooth-like point at apex; abdomen with a few short setae, more prominent in ventro-lateral region; spiracles black.

The immature stages are similar to those of P. charops , but in P. cheops the finalinstar larva possesses a less pronounced transverse band of setae on the metathorax and abdominal segment 1, and the pupa possesses a few short setae on the abdominal segments, which are absent in P. charops . Pereute cheops lacks the small subdorsal protuberance on abdominal segment 9 which is present in P. charops .

Larval food plants

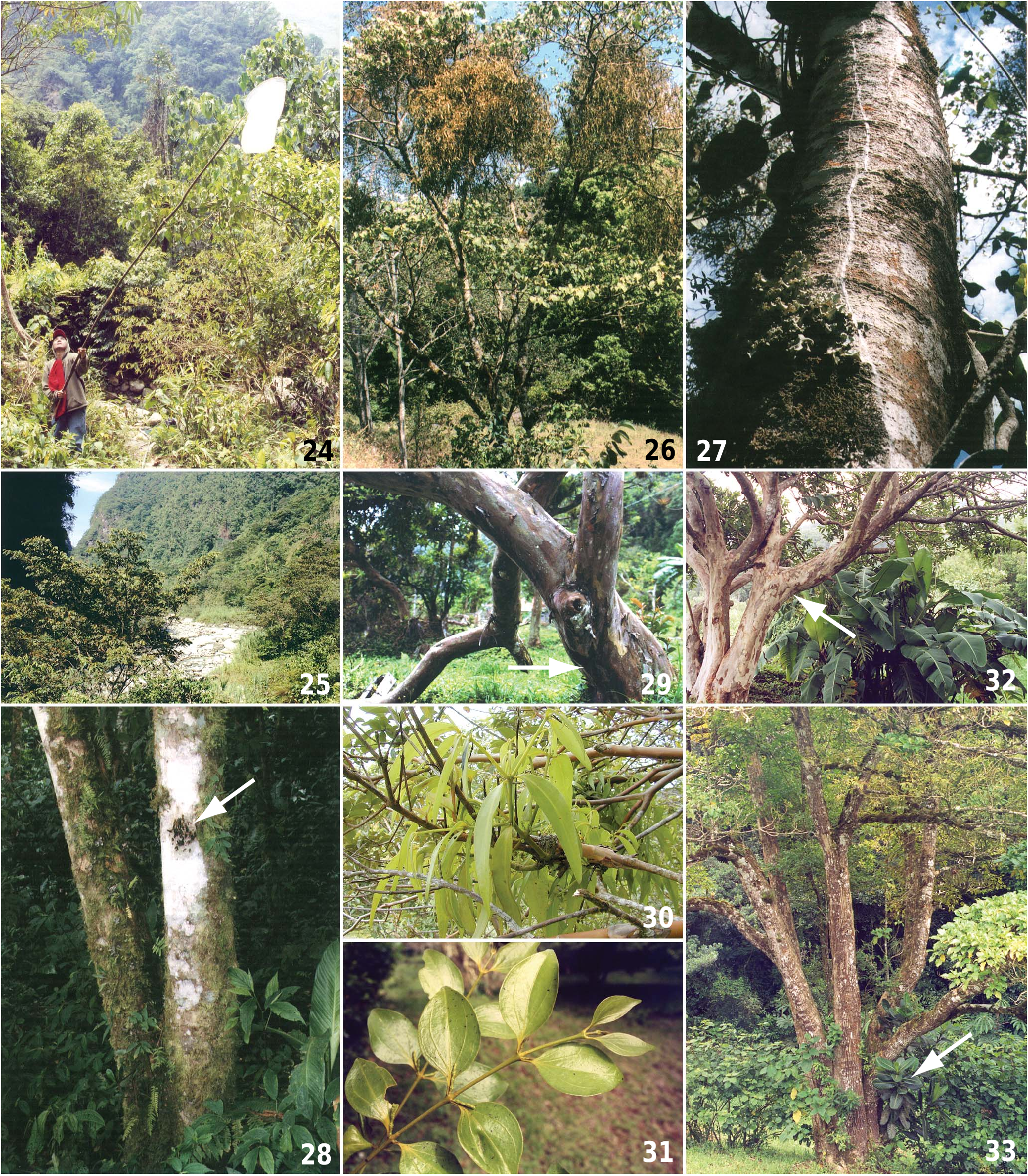

In Costa Rica, four cohorts of the immature stages were found associated with Phoradendron tonduzii parasitizing Croton (Euphorbiaceae) growing in disturbed habitat ( Figure 26 View Figures 24–33 ) ( Appendix 1).

Biology

The egg-laying habits were not recorded, but DeVries (1986, 1987) observed a female lay a single cluster of eggs and noted that the first-instar larvae feed gregariously. At Copey, we found two cohorts comprising final-instar larvae ( n = c. 50) and prepupaepupae ( n = 6) at the base of the trunk of the host tree. The larvae were monitored in the field over a three-week period in February–March 2000. During the day the larvae sheltered gregariously in a lose silken “nest” amongst soil, leaf litter, bark, debris and moss at the base of the trunk of the host tree; most larvae were in fact hidden beneath debris and loose soil. A narrow but conspicuous silken trail, approximately 1–3 mm wide, extended a distance of 10 m along the main trunk, from the larval “nest” to a mistletoe clump growing in the canopy of the host tree ( Figure 27 View Figures 24–33 ). During the morning and early afternoon (09:30–14:00 h), larvae were observed to avoid direct sunlight by moving to the most shaded part of the trunk/ground with changing position of the sun. When molested or disturbed they raised the head back and released a green fluid from the mouth. On 5 February, a sample of larvae ( n = 26) was held in captivity for 24 h before being released; the larvae were observed to spin large quantities of silk over the mistletoe foliage and branches for mobility before proceeding to eat the leaves at night. By 17 February, less than half of the cohort ( n = 23) remained, and these larvae had moved from the “nest” at the base of the host tree to a narrow fork in the main trunk approximately one metre from ground level where they were well concealed. The larvae did not feed but remained settled in a compact cluster in the fork of the host tree and some were entering the prepupal stage. About a week later (27 February) the larvae pupated. The pupae were tightly clustered together and aligned vertically head upward, attached by the cremaster and a central girdle to a large silken web spun over the surface of the trunk. When molested or touched the pupae wriggled or twitched with sudden jerky movements. Prior to emergence, the red median band of the fore wing of females was visible through the pupal wing case. In captivity, adults emerged synchronously (over a two-day period, but mostly within 12 h) and fully expanded their wings within about 45 min of emergence; however, the wings were soft and adults were not able to fly until 18–24 h later. During this period they sat motionless until their wings were fully hardened.

We did not observe adults ( Figure 8 View Figures 4–13 ) in the field, but males have been noted to fly high over the forest canopy where they patrol a territory around the tops of several trees in long, circling, gliding flights with minimal wing beat; such flights may last for several hours without pausing to rest ( DeVries 1987). In captivity, we noticed that females, when settled, kept their wings closed, but slowly raised the fore wing just past the hind wing to expose the brilliant orange median band on underside of the fore wing, which contrasted sharply against the black ground colour; after a period the fore wing was then lowered and withdrawn behind the hind wing, first slowly and then more rapidly, rendering the wings wholly dark brown-black, the effect of which made the butterfly difficult to detect.

The developmental time of the life cycle was not recorded, but in captivity the pupal duration lasted 18 d.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |