Tragelaphus selousi, Rothschild, 1898

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6512484 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6636778 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F50713-996F-FFD5-0644-F871FDC1F2FB |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Tragelaphus selousi |

| status |

|

Zambezi Sitatunga

French: Sitatunga du Zambeéze / German: Sambesi-Sitatunga / Spanish: Sitatunga del Zambeze

Other common names: Selous’s Sitatunga, Zambezi Marsh Buck

Taxonomy. Tragelaphus selousi Rothschild, 1898 ,

Zambezi Valley.

The Zambezi Sitatunga was formerly considered a subspecies of T. spekii , but it is diagnostically different from other sitatunga. The new separation of T. spekii into five species, each with its own nomenclatural history, makes demarcation of current ranges difficult. Monotypic.

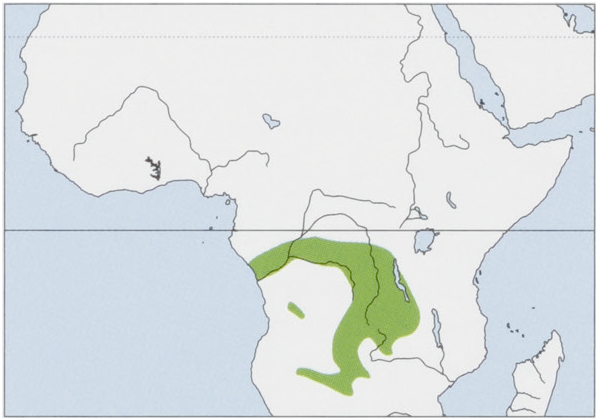

Distribution. Discontinuous and limited to wetland environments from S Republic of the Congo through C DR Congo and SW Tanzania, S to Zambia, Angola, and Botswana. Maps and distributional information here are provisional pending future research. View Figure

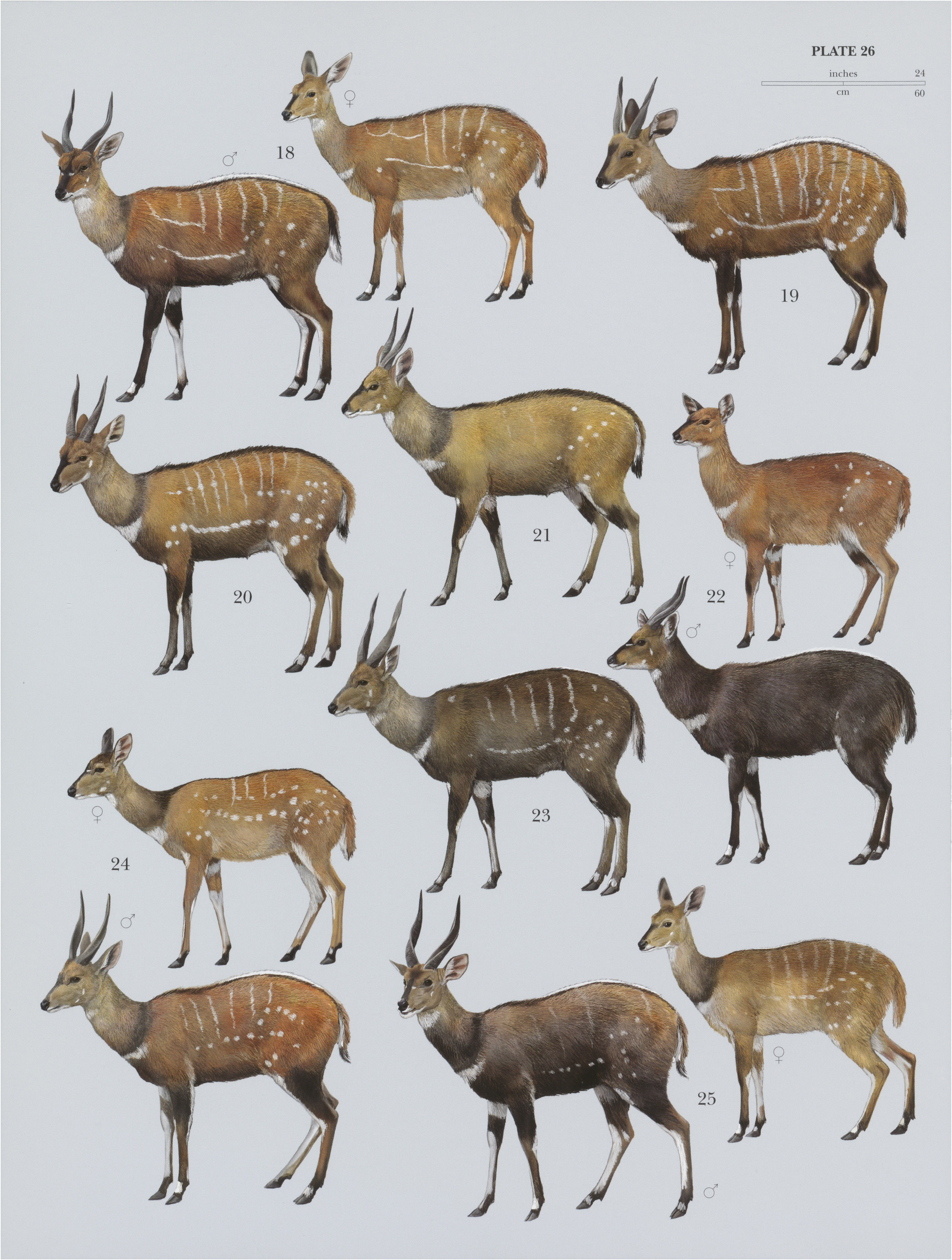

Descriptive notes. Head-body 115-170 cm,tail 30-35 cm, shoulder height 88-125 cm (males) and 75-90 cm (females); weight 75-125 kg (males) and 50-57 kg (females). These measurements are general for the sitatunga group and should be considered provisional until further information is available, although the Zambezi Sitatunga initially was described as larger than the Lake Victoria Sitatunga (7. spekit) and comparable to the Western Sitatunga (7. gratus ). Sitatungas are among the most sexually dimorphic tragelaphines relative to body weight, with mass of males as much as 170% that of females. Unique to the sitatunga group, the hooves of all but the Nkosi Island Sitatunga (7. sylvestris ) are very elongated, with flexible toe joints and large false hooves, which helps prevent them from sinking into the mud and vegetation mats of their preferred swampy habitats but makes them clumsy on dryland. The pelage tends to be shaggy, oily, and water-repellent, and males develop a scraggly mane as they age. Unlike other sitatungas, both sexes of the Zambezi Sitatunga are gray-brown to brown, with prominent preorbital spots in males and faint or obsolete preorbital spots in females. One female museum specimen had a faint lateral line and rump spots. Young Zambezi Sitatungas have long, dull-brown hair, faint preorbital spots, a dark dorsal stripe, a faint lateral line of spots, rump spots, and hints of stripes. Zambezi Sitatungas from Bangweulu, Zambia, are mostly as described above, but one museum specimen was pale yellow-brown. Variation in the skull is considerable among the various populations of the Zambezi Sitatunga; e.g. those from Bangweulu are longer-faced and have relatively longer horns than those from the Okavango Delta, Botswana, which may be taken as representing true Zambezi Sitatungas. Male-only keeled horns are spiraled 1-5 times and average about 58 cm in length, with a recorded maximum of 91-1 cm on fully mature males. Dental formula is 10/3, C 0/1, P.3/3,M3/8(x2) = 32.

Habitat. Sitatungas as a group, except the Nkosi Island Sitatunga, are described as semi-aquatic, limiting most of their activities to the swamps and marshes associated with rivers, lakes, and lowland forests of poor drainage that are scattered intermittently throughout their range. They are excellent swimmers and will avoid danger by escaping to deep water. A sitatunga can submerge its entire body, with little more than its nostrils above the surface. In the Okavango Delta, Botswana, Zambezi Sitatungas are restricted to perennial swamps of papyrus (Cyperus papyrus) and phragmites (Phragmites mauritianus); their use of other habitats is very dependent on seasonal flooding of the Delta. During periods of high water (January-June), Zambezi Sitatungas are driven from their preferred papyrus/phragmites habitats and use upland fringes of shallowly flooded grasslands. They return to papyrus/phragmites stands when water levels recede and establish well-developed paths and bedding sites among the reed beds.

Food and Feeding. Herbivorous and often described as intermediate feeders, Zambezi Sitatungas are not considered to be selective feeders and consume many species in proportion to their availabilities. In the Okavango Delta, seasonal differences in diet occur relative to flooding regimes. During low-water periods, when they are confined to marshes, their diets may be composed oflittle more than papyrus; 80% of papyrus umbels are consumed when available. During periods of high water, Zambezi Sitatungas spend more time in upland wooded areas and islands, where leaves of the trees Acacia nigrescens and Diospyrus mespiliformis are browsed heavily, even to the point of being denuded. Sprouts of a fern Cyclosurus interruptus and a grass Eragrostis inamoena on burned areas are attractive to Zambezi Sitatunga.

Breeding. The peak birthing season of the Zambezi Sitatunga has been reported to occur in June-July, with most of the breeding in January-February, during the rainy season. Otherwise, little is known about variation among populations, but they are probably comparable to other sitatunga species. Young Zambezi Sitatungas may remain hidden longer than other sitatunga species.

Activity patterns. Feeding activities of Zambezi Sitatungas are most pronounced in the morning and evening, mainly from 06:00 h to 09:00-10:00 h in the Okavango Delta. Their nocturnal activities there, outside of the protection of papyrus/phragmites marshes, were directly related to the phase of the moon; far fewer animals moved into upland grassy areas just prior to and during a full moon. Time spent feeding during low-water conditions differed between males (34% of their time) and females (77%) in the Okavango Delta.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Zambezi Sitatungas in the Okavango Delta appear to move little during seasonal flooding, which forces them into less preferred habitats of shallowly flooded grasslands; under such conditions, three young males were never observed more than 100 m from their original sightings. Densities in the Okavango Delta were 0-8 ind/km?. As a group, sitatungas are not very gregarious, and adults tend to occur alone except during breeding. True to form, 60% of Zambezi Sitatungas in the Okavango Delta occurred alone, and 34% in groups of only two individuals. About half of those were pairs of adult females. Immature and adult males were typically alone, indicating to the observers some level of intolerance and perhaps even exclusive home ranges. Males bark at each other throughout the year, suggesting a role in avoiding direct interactions. One Zambezi Sitatunga survived 16 years in captivity, which may be comparable to but is likely longer than in the wild.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List (under 7. spekii ), which does not differentiate the five species identified here. Generally, numbers of sitatungas are stable in areas of low human population density and decreasing elsewhere. As many as 170,000 sitatungas may occur discontinuously throughout the group’s range in Africa, with about 40% living in protected areas. That number, however,is considered an overestimate, and local populations are threatened by loss of habitat, altered hydrology of their critical wetland habitats, livestock grazing and likely associated disease transmission, uncontrolled burning of swampland, and overharvest for subsistence and the bushmeat trade. In the late 1990s, populations of Zambezi Sitatungas were said to be stable in Botswana and Zambia, particularly in the Bangweulu Swamps, Kafue National Park, and Kasanka National Park, but rare in the Kafue Flats and in Mozambique, Namibia, and Zimbabwe. In many parts of Africa, competition and disease transmission between livestock and wildlife are pressing conservation concerns. Successful control of the tsetse fly ( Glossina spp.), for example in the Okavango Delta, permitted expanded cattle grazing, bringing increased competition with wild bovids such as the Zambezi Sitatunga and other wildlife. Demand for water from an expanding human population can alter flow regimes, which subsequently reduces or eliminates wetlands critical to the Zambezi Sitatunga. Unregulated hunting and poaching for bushmeat also threaten conservation of the Zambezi Sitatunga. Minimizing loss of wetland habitats and,critically, their interconnectedness, which minimizes isolation and permits dispersal and gene flow, is fundamental to the long-term conservation ofall sitatunga, including the Zambezi Sitatunga.

Bibliography. Ansell (1972), Bro-Jorgensen (2008), Cotton (1935), East (1999), Estes (1991a, 1991b), Games (1983), Groves & Grubb (2011), Huffman (2004q), IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008bi), Kingdon (1982, 1997), Lydekker & Blaine (1914), Nowak (1999), Rothschild (1898), Smithers (1971), Walther (1964), Weigl (2005), Williamson (1986).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Tragelaphus selousi

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2011 |

Tragelaphus selousi

| Rothschild 1898 |