Kobus ellipsiprymnus (Ogilby, 1833)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6512484 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6636844 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03F50713-990A-FFB2-03C0-F55CFF1BF9A7 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Kobus ellipsiprymnus |

| status |

|

Ellipsen Waterbuck

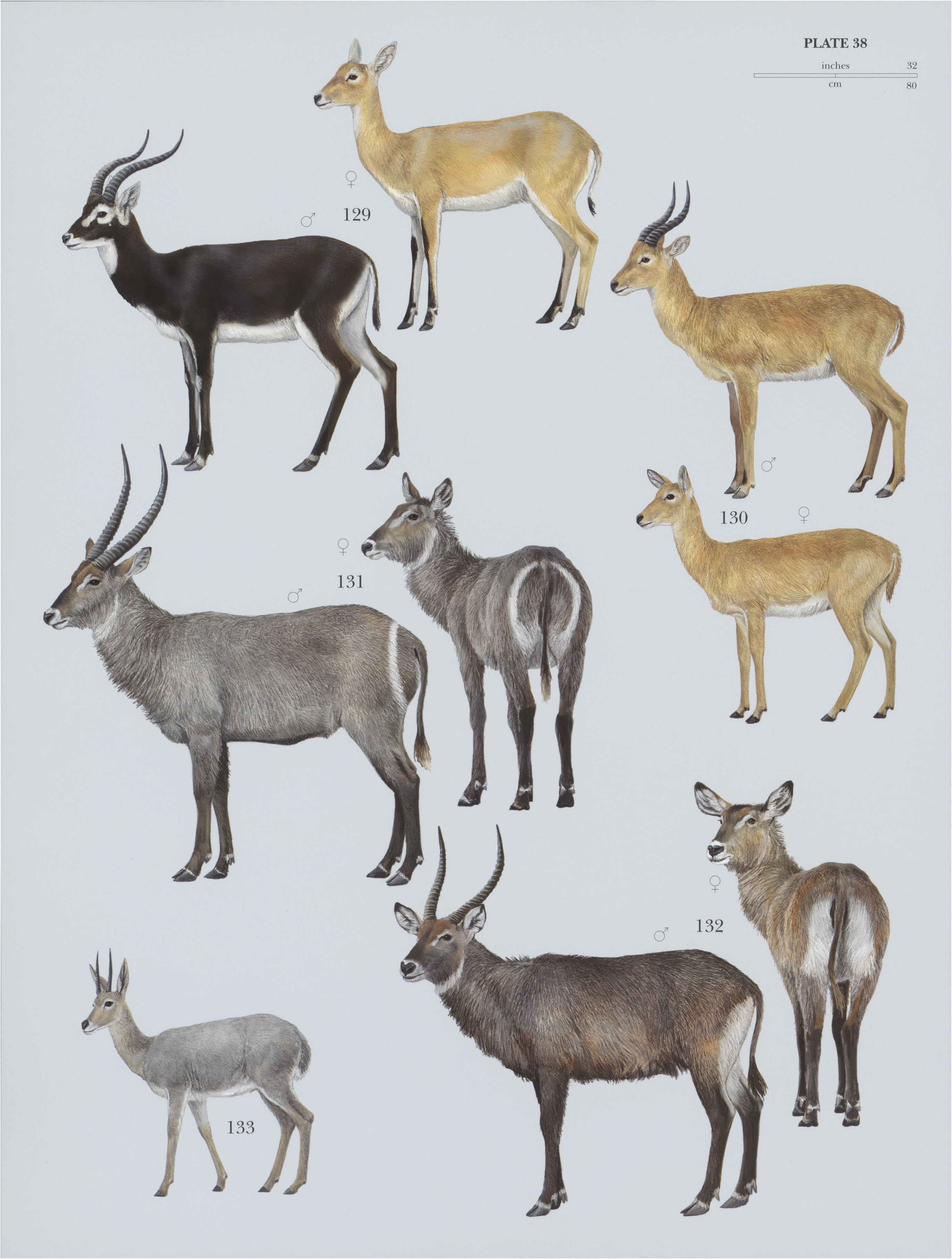

Kobus ellipsiprymnus View in CoL

French: Cobe a croissant / German: Ellipsen-Wasserbock / Spanish: Kob acuatico oriental

Other common names: Common Waterbuck

Taxonomy. Antilope ellipsiprymnus Ogilby, 1833 ,

district between Lataku and the west coast, South Africa.

Numerous subspecies of waterbucks have been described based on regional differences, but their validity requires additional study. Two broad groups of waterbucks are well recognized: Ellipsen Waterbuck and Defassa Waterbuck ( K. defassa ). These are treated as separate species here, although the latter is sometimes classified as a subspecies of K. ellipsiprymnus . Genetically, these two waterbuck groups are distinct, although hybridization occurs in regions of sympatry (e.g. Nairobi National Park and Samburu National Park, Kenya), resulting in intermediate phenotypes. Pending further review, this species is considered monotypic here.

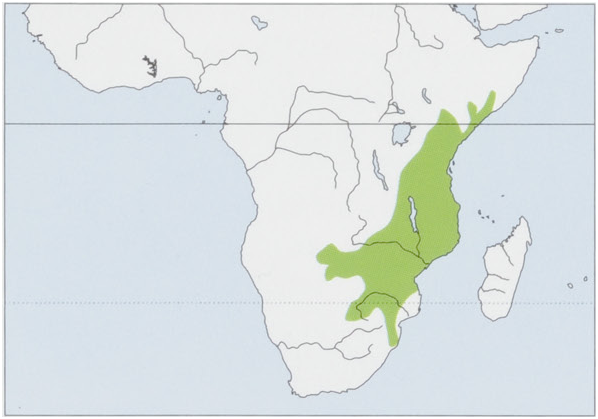

Distribution. S Somalia and E Kenya to E Botswana and NE South Africa. The distribution of the Ellipsen Waterbuck is separated from that of the Defassa Waterbuck by the Muchinga escarpment in Zambia; the two species coexist in C Kenya but are roughly separated by the Rift Valley. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 175-235 cm, tail 33-40 cm, shoulder height 120-136 cm; weight 250-275 kg (males) and 160-180 kg (females). The pelage is long, shaggy, and coated with an oily secretion. The hair on the neck is especially long and coarse and forms a rough mane. Overall color is a uniform gray-brown; each hair has a light base and dark tip, creating a grizzled appearance on close inspection. The dorsum is slightly darker than the flanks, and the underparts are scarcely paler except for the ventral midline, groin, inner thighs, and underside of the tail, which are white. A white band is present just above the hooves on the otherwise dark brown legs. The Ellipsen Waterbuck is readily distinguished from the related Defassa Waterbuck by a conspicuous white ring on the rump that runs above the base of the tail and circles the buttocks (in some individuals there is a gap in the white band at the base of the tail). The forehead is often brighter than the gray-brown cheeks, and a darker blaze is present from the eyes to the nose. A white line encircles the rhinarium, lips, and chin. White markings are also present at the medial corner of each eye, extending over the eye as a superciliary stripe. A white crescent-shaped bib marks the upper throat immediately below the angle of the jaw. The white markings of females (on both the face and rump) tend to be less conspicuous than those of males. The short, rounded ears are very hairy; the backs are dark and the inner surfaces white. Males alone possess horns; these lack the double-curvature typical of the genus Kobus and instead follow the profile of the nose before scooping upward. The basal three-quarters of each horn has heavy ridges. Horn length is typically 79-92 cm in mature males, with a tip-to-tip distance of 33-5— 74 cm. Dental formulais10/3, C0/1,P 3/3, M 3/3 (x2) = 32.

Habitat. Open grassland and wooded savanna, usually near water. Habitat selection is driven by food resources. During the rainy season, this species is often widespread in wooded areas (accounting for 42-72% of observations). In Zimbabwe, woodlands dominated by Brachystegia spp. and Hyparrhenia filipendula grasslands are preferred, although grassy areas with Loudetia simplex and Aristida junciformis are also used. As water becomes increasingly scarce during the hot-dry season (September—-November), Ellipsen Waterbucks alter their habitat use to exploit the green food resources in shoreline sedge habitats and shallow water papyrus beds. In favorable regions, the Ellipsen Waterbuck occurs at population densities of 2:6—4-8 ind/km?.

Food and Feeding. The Ellipsen Waterbuck is predominantly a grazer, although browse is seasonally consumed. In northern Botswana, perennial grasses comprise 92-100% of the diet based on observations of foraging individuals. Preferred species vary throughout the year and between regions as evidenced by several studies. Across the southern parts of its distribution, the perennial grasses Brachiaria spp., Cynodon dactylum, Digitaria spp., Heteropogon contortus, and Themeda triandra are generally consumed. Annual grasses, such as Panicum spp., are consumed primarily when the young plants are growing during the rains (generallyJanuary-March in southern Africa). The use of browse and ground-level forbs is concentrated in the dry season (May—-October) when grass quality decreases. Plant communities immediately surrounding permanent water provide the majority of forage consumed during the late dry season. Unlike the Defassa Waterbuck, Ellipsen Waterbucks will readily wade into water to forage, consuming mostly plant parts that extend above the surface of the water. Hydrophytic species found in the diet include Setaria spp., Hemarthria altissima, Cyperus spp., Phragmites spp., and Typha spp.

Breeding. Reproduction occurs throughout the year, although in Umfolozi Game Reserve, South Africa, births tend to occur in December—June (with a peak in February-March), a time when grassis plentiful. A courting male follows an estrous female while licking at her anogenital region, testing the female’s urine using an exaggerated flehmen response. Ritualized foreleg kicks (“laufschlag”) do not appear to be universal in the courtship of Ellipsen Waterbuck. The gestation period is estimated to be eight months, after which a single offspring is born. Infants spend the first 2—4 weeks oflife lying hidden in cover, with the mother visiting to nurse sporadically. After this lying-up period, offspring may group together in pairs or trios. Young Ellipsen Waterbucks are especially prone to infestations of the brown ear tick (Rhipicephalus appendiculatus) in January-March, which may lead to death; oxpeckers (Buphagus spp.) are not tolerated by waterbucks of any age. Both sexes of Ellipsen Waterbuck are slow to mature. Potential longevity in the wild is at least eleven years, and captive individuals have lived past 20 years.

Activity patterns. Ellipsen Waterbucks are most active around sunrise and sunset. Activity levels tend to be lowest around midday; resting may occur in shaded wooded areas or in the open. This pattern ofactivity and resting is poorly defined, and individuals or groups may be active at any time during the day. In the late afternoon, Ellipsen Waterbucks frequently emerge from cover into open grasslands. They may remain in the open at night, but nocturnal activity is poorly documented.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Females and juveniles live in small groups of up to 20 individuals. Group size is smallest during the rainy season, when the average is 4-4 ind/group, and highest during the hot-dry season, with an average of 6-9 ind/group. Female group composition is very flexible, with individuals joining and leaving on a daily basis. Perhaps as a result ofthis fluidity, there is no hierarchy or defined leader within these herds. Males are either solitary or live in bachelor groups of 4-6 males. In contrast to the flexible female groups, male herds are relatively stable and have a strong age-based hierarchy reinforced by sparring. Solitary adult males often (but not always) defend territories. Territory size appears to be based on resource availability rather than population density; the average size is 0-9 km*. Adjacent territories may have an area of overlap 50 m wide along their borders. Boundaries are maintained with ritualized broadside displays, with exaggerated head movements and postures to emphasize the horns of that resident male; vigorous horning of the ground or bushes may also signal territorial occupancy. Physical conflicts, usually tests of strength with horns locked together, occur primarily when a bachelor attempts to displace a territory holder. Relative to male territory size, female home range is very large: two females in Zimbabwe were found to range over 3-64 km* and 6-45 km®. Males thus defend prime feeding resources to attract females to their territory. This is most obvious during the hot-dry season, when all individuals concentrate around water sources. Bachelor males must forage within defended territories at this time; they are generally tolerated by territorial males except around shoreline zones of Phragmites—a habitat highly preferred by females. When food resources are more available during and following the rains, bachelor males disperse widely and avoid territories. Submissive displays, in which the head of the subdominant male is nodded up and down to flash the white collar, help reduce conflict when bachelor males infringe on territories. During these displays, the occupying male adopts a “proud” posture with the head held high and is able to send subordinate males off with a sharp forward sweep of the horns. The positioning of the tail also conveys important social signals; the conspicuous rump ring may help emphasize these movements.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List (as K. e. ellipsiprymnus ). The wild population has shown a declining trend; recent estimates place the population at approximately 105,000 individuals. The Ellipsen Waterbuck was once widespread wherever appropriate habitat was available, but because of the expansion of agriculture and settlement the species is now found in scattered populations and is often confined to protected areas. The largest numbers are found in South Africa and Kenya. Namibia, Malawi, Mozambique, and Swaziland have very low numbers. The Ellipsen Waterbuck formerly occurred in south-eastern Ethiopia (along the Shebelle River). This region has been extensively modified for agriculture and the speciesis believed to be regionally extinct.

Bibliography. Child & von Richter (1969), East (1999), Estes (1991a, 1991b), IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2008x), Lorenzen, Simonsen et al. (2006), Lydekker (1914), Melton (1983), Melton & Melton (1982), Smithers (1966), Tomlinson (1980a, 1980b, 1981), Von Richter & Osterberg (1977), de Vos & Dowsett (1966), Weigl (2005).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.