Calliax de Saint Laurent, 1973

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.3821.1.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:3F7440FB-B9A6-4669-A1B2-4DAB6CFEB6B7 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5117642 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03CA87CA-FFCB-C812-00A2-FB07FACCB745 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Calliax de Saint Laurent, 1973 |

| status |

|

Genus Calliax de Saint Laurent, 1973

Type species. — Callianassa (Callichirus) lobata de Gaillande & Lagardère, 1966 .

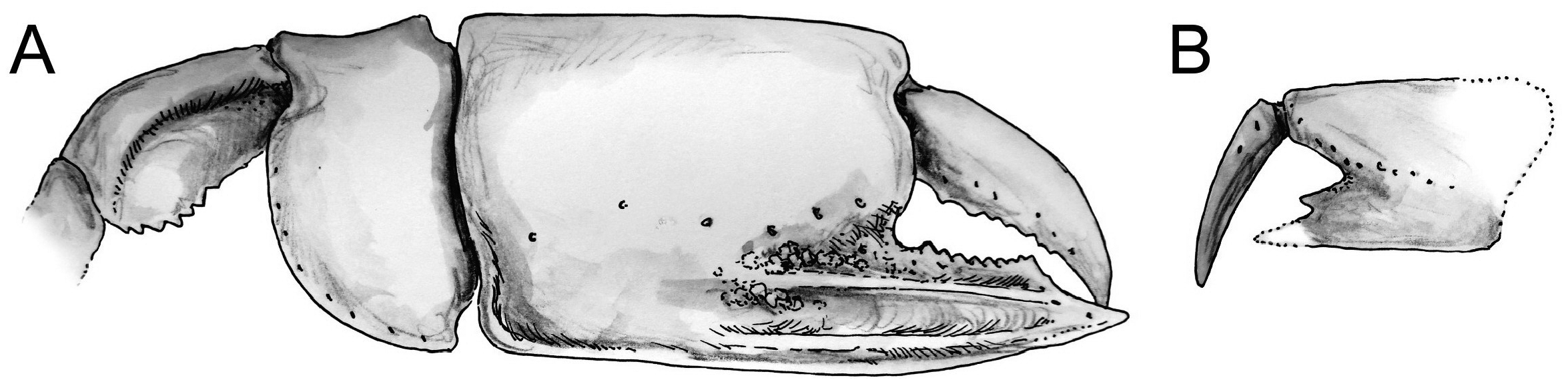

Extant species included. — Three species (including one referred species but not formally named): Calliax doerjesti Sakai, 1999 ( Figs 3A–B View FIGURE 3 ); Calliax lobata ( de Gaillande & Lagardère, 1966) ( Figs 3C–D View FIGURE 3 ); Calliax sp. sensu Taviani et al. (2013).

Fossil species included.– Calliax michelottii (A. Milne Edwards, 1860) comb. nov. More fossil occurrences in open nomenclature are recognized (see Table 1 View TABLE 1 ).

Diagnosis. Carapace lacking dorsal oval; rostrum short, with blunt tip, rostral spine absent. Pleonal segment 2 longest, no lateral tufts of setae on segments 3–5. Telson slightly wider than long, lateral margin curved, posterior margin straight or slightly convex. Eyestalk about twice as long as wide, slightly flattened dorso-ventrally; cornea small, weakly pigmented. A1 peduncle shorter than that of A2. Mxp1 epipod tapering anteriorly. Mxp2 with small, leaf-like epipod. Mxp3 subpediform (sensu Ngoc-Ho 2003), propodus and dactylus rounded, exopod absent. P1 unequal, dissimilar. Major P1 propodus rectangular, usually longer than high, fixed finger shorter than manus, with a double ridge accompanied by a furrow extending onto manus and parallel to the lower margin of propodus. Fixed finger as long as dactylus in major P1, shorter than dactylus in minor P1, with wide proximal gap and large triangular proximal tooth on cutting edge. Major P1 carpus shorter than high, distinctly shorter than propodus. Major P1 merus longer than high, keeled, lower margin armed with small spines. P3 with small proximal heel on propodus, P5 subchelate. Paired arthrobranch on Mxp3 and P1–4. Male and female Plp1 uniramous male and female Plp2 biramous, all lacking appendix interna, male Plp2 with appendix masculina overreaching endopod. Plp3–5 biramous, foliaceous, appendix interna finger-like in both sexes. Uropodal endopod and exopod slightly longer than telson, with rounded posterior margin; exopod with dorsal plate terminating in short distal setal row [emended from Ngoc-Ho (2003: 489) with characters on major P1].

Remarks on the taxonomy. Calliax has a complex taxonomic history. The genus was erected by de Saint Laurent (1973) with Callianassa lobata de Gaillande & Lagardère, 1966 , as the type species. Since then the concept of the genus has been changed several times (cf. Manning & Felder 1991; Sakai 1999, 2005, 2011; Ngoc- Ho 2003; Hyžný 2012; see also Dworschak 2007). Here the view of Ngoc-Ho (2003) and Sakai (2011) is adopted, and thus, only two formally described extant species are recognized. Discussion on distinguishing Calliax from related taxa based on soft-part morphology was provided by Ngoc-Ho (2003) and will not be repeated here.

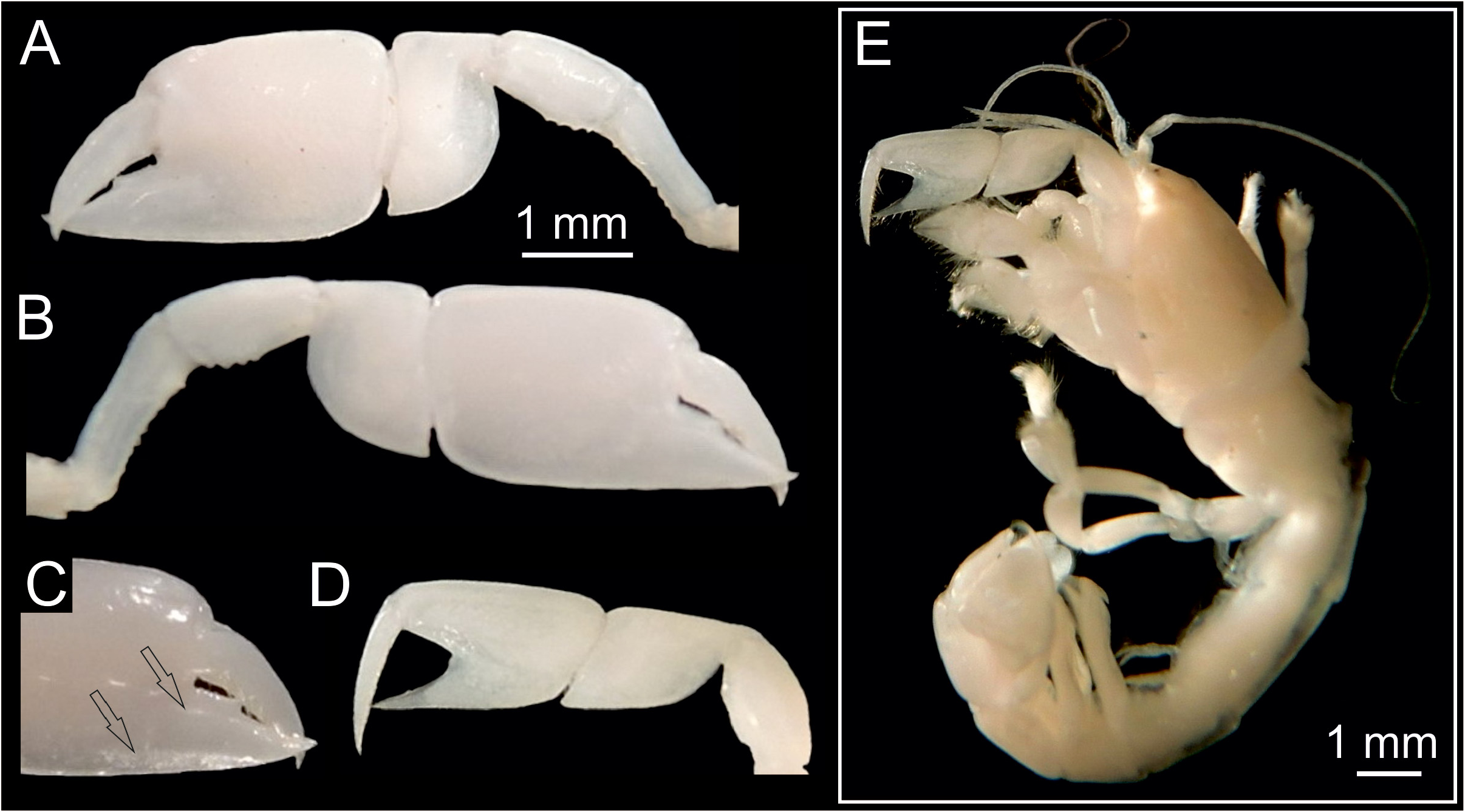

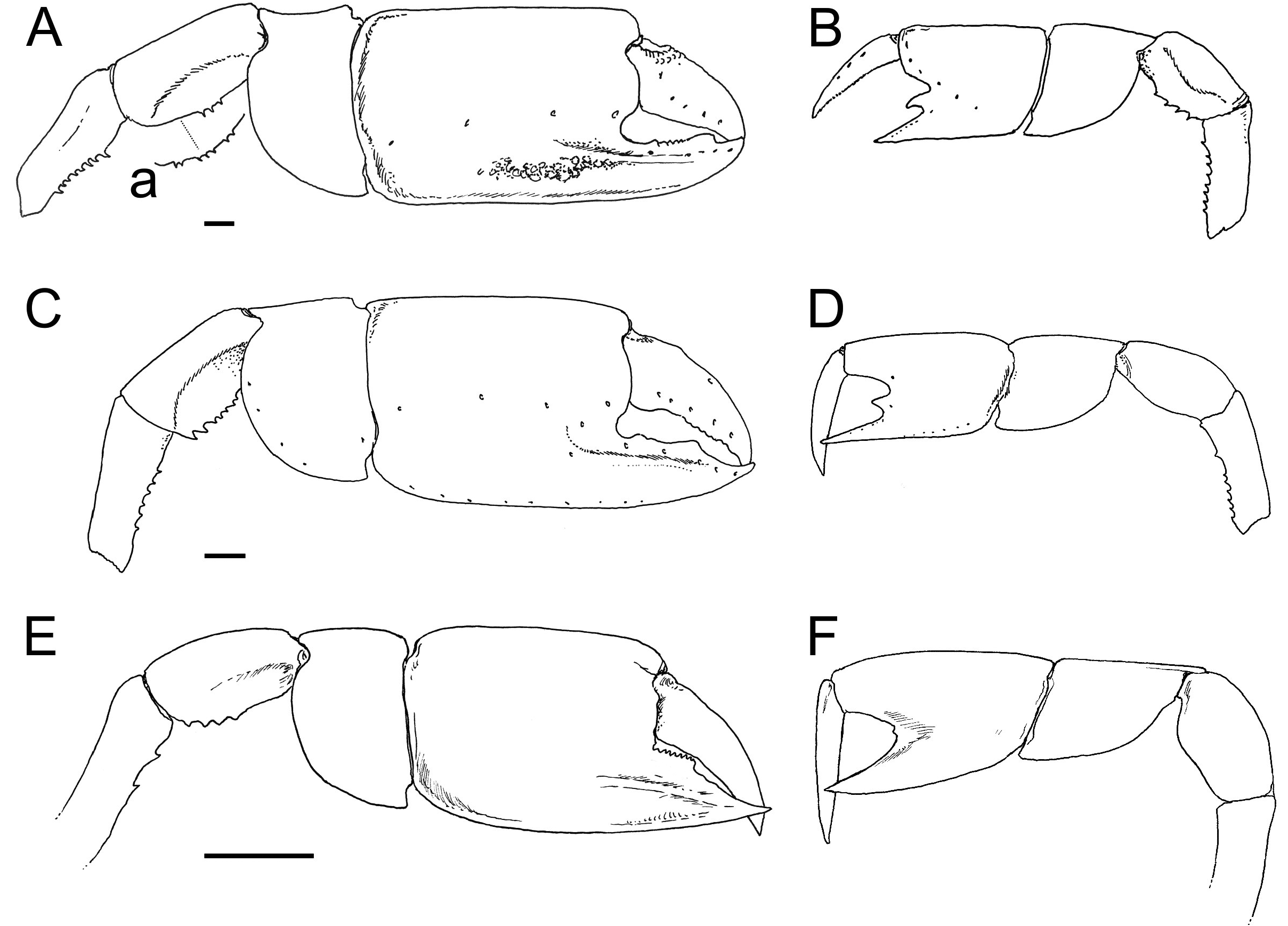

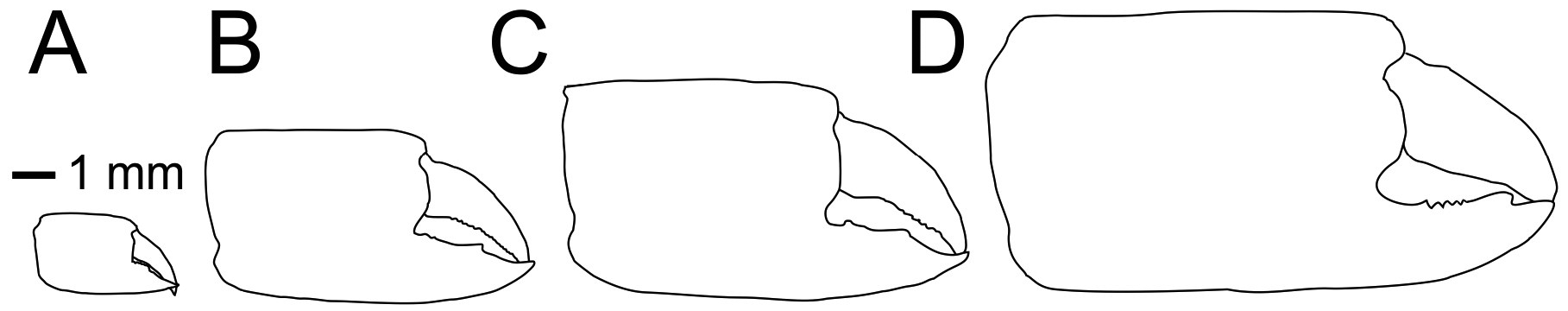

When dealing with chelipeds the two known extant species of Calliax can be characterized by unequal and dissimilar chelae, from which the minor one has „fixed finger shorter than and separated from the dactylus by a wide gap, bearing a large triangular proximal tooth ( Ngoc-Ho 2003: 490)“. This morphology approaches a subchelate cheliped state. Comparison of the illustrated major P1 propodus of C. lobata ( de Gaillande & Lagardère 1966: fig. 2a; de Saint Laurent & Božić 1976: fig. 23; Ngoc-Ho 2003: fig. 17D), C. doerjesti ( Sakai 1999: figs. 28, 29b) and Calliax sp. ( Taviani et al. 2013: fig. 8) clearly shows consistency in its general shape, i.e. propodus is rectangular and usually longer than high and on its lateral surface the fixed finger possesses two ridges accompanied by furrow (or furrows) parallel to the lower margin of propodus and extending onto manus. The ridges are visible especially when viewing under low angle light ( Fig. 2C View FIGURE 2 ). There are several distinct setal pores (accompanied by tubercles) arranged obliquely across the lateral surface of propodus. In Calliax the major P1 carpus is always much shorter than manus, with rounded proximo-lower margin ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3 ). The merus is longer than high with a distinct meral keel and its lower margin is usually armed with small spines. The above mentioned combination of the characters of minor chela and major propodus, carpus and merus is unique for Calliax ; thus, the genus can be identified on the basis of chelipeds alone.

The number of spines on the lower margin of P1 merus may vary between respective members of Calliax and may help in distinguishing taxa at the species level, although possible variation has not been studied in detail yet. Regarding the number of meral spines, there are discrepancies in the literature. Sakai (1999: 114) in the description of C. doerjesti mentioned that the lower margin of the merus was “armed with three interspaced denticles”. One of the figures ( Sakai 1999: fig. 29b) indeed shows three small spines, however, in the other one ( Sakai 1999: fig. 28) depicting the same specimen (holotype) the merus is armed with seven spines ( Fig. 3a View FIGURE 3 ). Ngoc-Ho (2003: fig. 17D; note that the published figure depicts the right major chela, whereas the caption refers to it as the left one) figured the holotype (male) of C. lobata with seven spines on the merus and de Saint Laurent & Božić (1976: fig. 23a) figured a female specimen of C. lobata also with seven spines. Calliax cf. C. lobata , examined and figured herein ( Figs 2 View FIGURE 2 , 3E–F View FIGURE 3 ), possesses only four blunt spines, presumably mirroring its small size ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4 ).

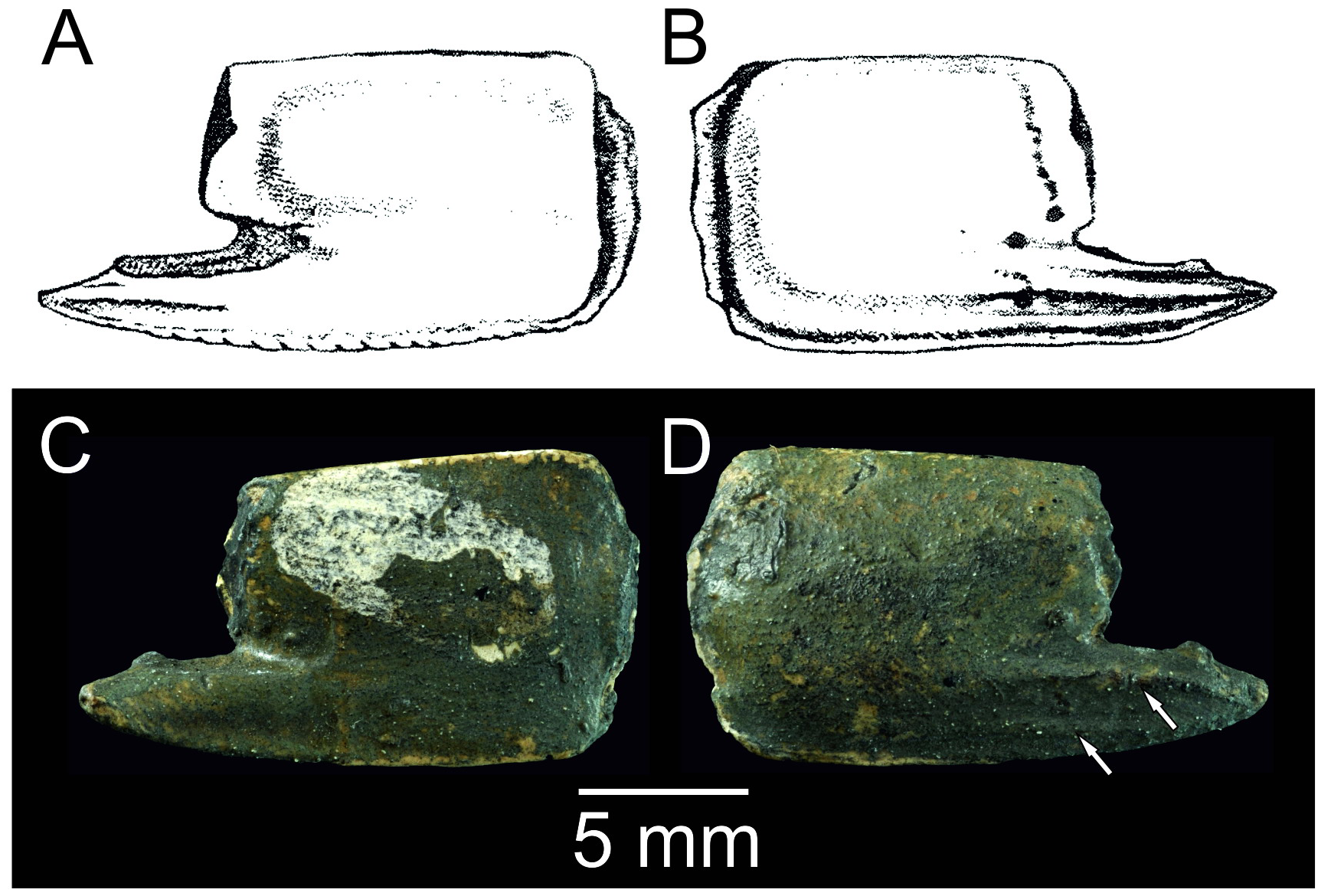

Remarks on the fossil record. Articulated chelipeds are relatively sparse in the fossil state and often only isolated propodi are at hand. In this respect, the major P1 propodus of Calliax is distinct enough to be differentiated from all other ghost shrimp genera. It must be stressed, however, that the more cheliped elements are found, the more secure assignment at the genus level can be provided.

The best preserved and most numerous remains of Calliax in the fossil record belong to species originally described as Callianassa michelottii ( Figs 5–10 View FIGURE 5 View FIGURE 6 View FIGURE 7 View FIGURE 8 View FIGURE 9 View FIGURE 10 ). It is discussed in detail below.

Feldmann et al. (2005) reported several isolated cheliped elements from the Miocene of the Navidad Formation of Chile as Callianassoidea sp. 1. Although the authors stated that it does not resemble any callianassoid genus ( Feldmann et al. 2005: 431), the figured material ( Feldmann et al. 2005: fig. 2A) exhibits striking similarities with Calliax as discussed herein. Interestingly, Callianassa szobensis Müller, 1984 , which is herein considered a junior subjective synonym of C. michelottii (see below) and hence a member of Calliax , is mentioned by Feldmann et al. (2005) as similar to their Callianassoidea sp. 1. The same locality also yielded another specimen which has been identified as Callichirus sp. The figured propodus ( Feldmann et al. 2005: fig. 2A) shows a relatively short manus; however, the fixed finger with ridges and a furrow indicates its affinities to Callianassoidea sp. 1 ( Feldmann et al. 2005: fig. 2D). Both specimens are treated here as Calliax sp. 1 .

Feldmann et al. (2011) reported fragmented material from the Miocene of Tierra del Fuego ( Argentina) as “Cheliped Form B” of indeterminate callianassoid. As already noted by Hyžný & Hudáčková (2012: 13), the minor chela exhibits remarkable similarities to Calliax , ( Feldmann et al. 2011: fig. 5E) showing a fixed finger shorter than the dactylus and separated from it by a wide gap with a proximal tooth (cf. Ngoc-Ho 2003: 490). The major P1 propodus ( Feldmann et al. 2011: fig. 5B), however, does not possess the ridges on the fixed finger. It is fairly likely that the two specimens do not belong to the same taxon, as they were not found associated with each other. For the purposes of this contribution only the minor chela is referred to here as Calliax sp. 2 .

Charbonnier et al. (2013) reported a single near-complete propodus from the Paleocene of Pakistan identified as a minor chela of Calliax . Indeed, the specimen shows all features typical for minor chelae of the genus ( Charbonnier et al. 2013: fig. 2) as discussed above. This occurrence is considered the oldest confirmed fossil record of the genus, treated here as Calliax sp. 3 .

Callianassa whiteavesi Woodward, 1896 from the Campanian of Canada ( Woodward 1896; Feldmann & McPherson 1980; Schweitzer et al. 2003) was assigned to Calliax by Schweitzer et al. (2003). The material is rich and sufficiently preserved to reconstruct both chelipeds ( Feldmann & McPherson 1980). The species differs markedly from any Calliax species. It does not possess the typically shaped minor cheliped as discussed above, nor has it parallel ridges on the base of the fixed finger. Moreover, some specimens exhibit a rather deep dactylus, a character not observed in Calliax . As a result, the species is excluded from Calliax herein. Until the type material is restudied we suggest to keep the species under Callianassa sensu lato.

Swen et al. (2001) reported a single fragmentary right propodus from the Maastrichtian of the Netherlands as “ Calliax ? sp.”. The material is too fragmentary for resolving its generic status. The oblique development of the ridge at the base of fixed finger ( Swen et al. 2001: fig. 5.3), however, points to closer affinities to Eucalliax or Calliaxina rather than Calliax .

Van Bakel et al. (2006) listed in a table of Cenozoic decapods from Belgium the presence of Calliax in the Miocene strata. The material was recently described as a new member of the family Axiidae ( Fraaije et al. 2011) .

Occurrence and distribution. Paleocene–Holocene. Two formally described extant species are known from West Atlantic (Florida) and Mediterranean ( Sakai 2011). Based on the reports discussed above ( Feldmann et al. 2005, 2011), the geographical distribution of the genus was much wider during the Miocene than today, and the genus was apparently also present in the East Pacific (see below). All occurrences are reviewed in Table 1 View TABLE 1 .

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |