Pteropus poliocephalus, Temminck, 1825

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6448815 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6794764 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03AD87FA-FF9B-F675-8968-33E4F691F217 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Pteropus poliocephalus |

| status |

|

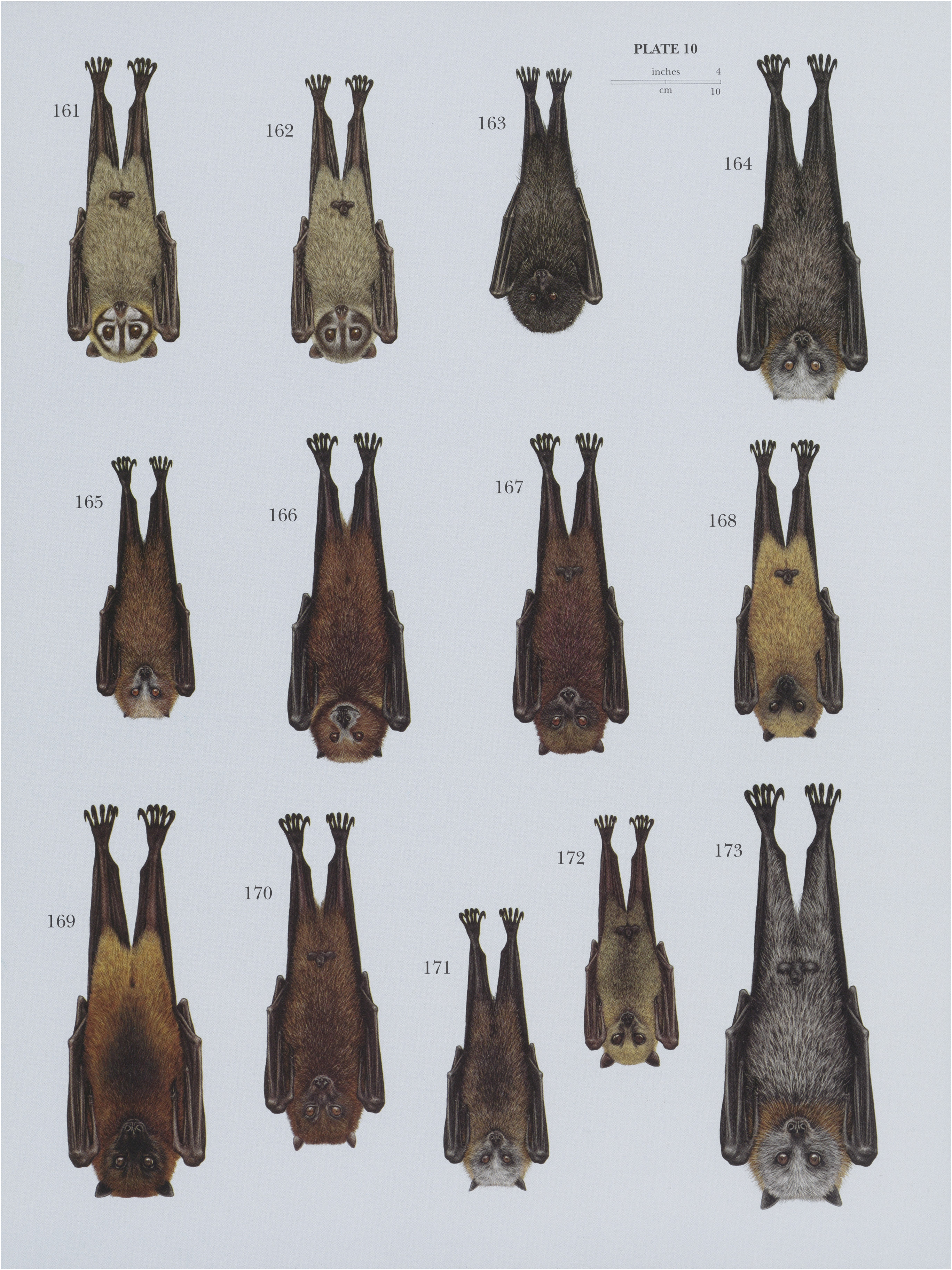

173. View Plate 10: Pteropodidae

Gray-headed Flying Fox

Pteropus poliocephalus View in CoL

French: Roussette a téte grise / German: Graukopf-Flughund / Spanish: Zorro volador de cabeza gris

Taxonomy. Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck, 1825 View in CoL ,

Australia.

Pteropus poliocephalus is the only member of the poliocephalus species group. Monotypic.

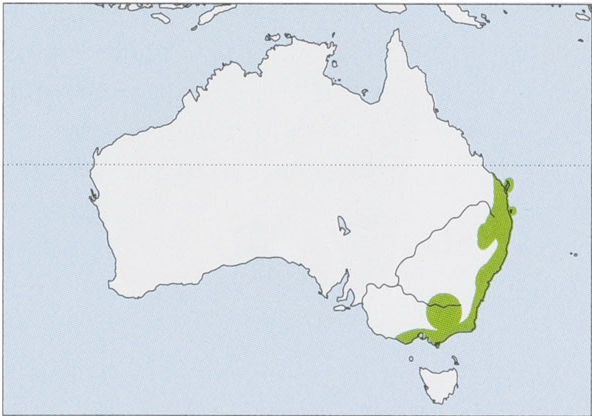

Distribution. Endemic to E coast ofAustral-1a, ranging from SE Queensland (including Fraser, Moreton, and North Stradbrooke Is) through New South Wales to Victoria. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 220- 280 mm (tailless), ear 19-39 mm, hindfoot 34-44 mm, forearm 151-177 mm; weight 0-41.1- 3 kg. Males and females differ in weight but have similar forearm lengths. Head of the Gray-headed Flying Fox is light gray but can vary in shades. Furis long and dense all over, including on dorsal side of humerus, proximal one-half of forearm, and down tibia to ankle. Body pelage has primarily two types of hairs: one long and dark gray and the other light gray to silver. Mantle is rusty brown to russet and forms complete collar around neck. Belly fur has flecks of white and bufty hairs. Long hairs are dark brown at bases. Wing membranes are dark brown to black. Skull is pteropine, with large orbits and undeveloped or low sagittal crest. Zygomatic arches are unusually slender. Coronoid is weak, with low coronoid height. Canines are long, slender with narrow cingulum, and nearly straight (lower canines are slightly more recurved). Front face of C' has deep vertical groove. P? and P* are shorter than usually found in flying foxes. M? is slightly larger than P|. Diploid number is 2n = 38, with 32 metacentric or submetacentric and four acrocentric autosomes. X-chromosome is submetacentric, and Y-chromosome is acrocentric and minute.

Habitat. Historically forests and mangroves in coastal lowlands of south-eastern Australia, usually roosting near water in stands of forests of native species such as paperbark ( Melaleuca spp. , Myrtaceae ) and Casuarina (Casuarinaceae) or cultivated species. The Gray-headed Flying Fox lives much further south than other species offlying foxes and can tolerate frosty temperatures. It can be found in botanical gardens in Melbourne, Australia, which is a 450 km extension ofits historic distribution. Urban development has made the area warmer and more humid, with high levels of precipitation, and has also brought more potential food sources due to cultivation of new trees and shrubs species that provide year-round foraging opportunities. Colonies are usually near a freshwater source.

Food and Feeding. The Gray-headed Flying Fox feeds in canopies on a wide variety of fruits, flowers, pollen, nectar, and, on rare occasions, leaves from more than 200 plant species from 50 families. Most of the diet is flowers from Myrtaceae , particularly multiple eucalypt species ( Melaleuca salicina, Syncarpia glomulifera, Eucalyptus spp. , Corymbia spp. , Angophora spp. , and Melaleuca spp. ), Proteaceae ( Banksia spp. , Grevillea robusta , and Stenocarpus sinuatus), and Fabaceae ( Castanospermum australe). Many Myrtaceae species do not flower reliably every year, resulting in variations in foraging sites. Various native and cultivated fruits are also eaten, especially native figs ( Ficus spp. , Moraceae ). When food resources are scarce, the Gray-headed Flying Fox is more likely to raid orchards or other introduced plants including Cinnamomum camphora ( Lauraceae ), Celtis spp. (Cannabaceae) , Ligustrum spp. (Oleaceae) , and Psidium spp. (Myrtaceae) . In areas where it overlaps with the Black Flying Fox ( P. alecto ), diets are similar, but it is unclearif there are differences in foraging behavior or diet preferences.

Breeding. The Gray-headed Flying Fox breeds seasonally and reproduces once a year, with females giving birth to one young in October-December. Birthing period coincides with fruit harvest season in many parts of New South Wales and does not shift significantly from year to year, despite earlier suggestions that breeding occurred opportunistically in response to resource shifts. Mating occurs primarily in March-April. Gestation lasts six months; lactation lasts 3-4 months. Females reach sexual maturity in their second year, but few females younger than three years are thought to be able to raise young to adulthood. Males are always sexually active but begin establishing territories and harems in January, with increasing frequencies of copulations in February and testes swelling in March. Females do not conceive before April despite sperm being available, and it is unclear what prevents conception. Males have been known to copulate out of season with females, even after testes have regressed, resulting in late conception. This was verified experimentally in captive colonies, and lactation does not inhibit ovulation. Mass abortions and premature births have been recorded in response to environmental stress. Females can conceive again after abortion, but there is limited time for them to do so. Starting at one month of age, young are left at roosts when mothers go to forage (October-December). Young begin to forage with the mothers in January-February and are weaned in late February to March. Young then segregate to outer edges of colonies to avoid adult males arriving to establish their territories for the new mating cycle. The Gray-headed Flying Fox occasionally hybridizes with the cooccurring Black Flying Fox and possibly the Spectacled Flying Fox ( P. conspicillatus ).

Activity patterns. Gray-headed Flying Foxes are nocturnal. They leave roosts around dusk to forage and return around dawn. During the day, they rest at roost sites and exhibit typical pteropodine activity, such as wing fanning and occasional conspecific territorial interactions.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Gray-headed Flying Fox is generally gregarious and roosts colonially, at times in groups of 20,000-30,000 individuals. Total population spread across coastal eastern Australia is considered to be in a single, mobile population of 320,000-435,000 individuals. Individuals have been recorded to fly as far as 40 km to feed, but most foraging distances are c. 20 km. It does not have adaptations to withstand food shortages, and there are few areas in its distribution where nectar is available continuously throughout the year, meaning it must migrate in response to changing food availability. The Gray-headed Flying Fox has historically migrated south in summerto cooler climates and north in winter to warmer climates, along with responding to where food becomes available, with some adults dispersing as far as 750 km. Migration does not occur as a unit; hence, colonies are found at smaller sizes than the total population size. Occasionally, Gray-headed Flying Foxes co-roost with Black Flying Foxes, Spectacled Flying Foxes, and Little Red Flying Foxes ( P. scapulatus ), but they maintain spatial segregation.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. There has been contraction of northern extent of distribution greater than 500 km in the past 100 years, with an expansion of ¢. 750 km in the south and increasing numbers of permanent colonies. The Gray-headed Flying Fox is experiencing continued population decline, estimated to have been more than 30% in the last three generations as inferred by direct observation, shrinkage in distribution, loss of overwintering habitat, and probably competition and hybridization with co-occurring Black Flying Foxes. Major threatis loss of foraging and roosting habitat to land conversion for agriculture, agroforestry, and urban development. Additional threats include electrocution on power lines, entanglement on barbed wire or netting, and extreme weather events. Climate change will also contribute to loss of habitat and likely increase frequency of human-wildlife conflict or heatrelated mortality events. There has been an increase in persecution offlying foxes in general due to public concerns about diseases, smell, and noise associated with large colonies, particularly as colonies move into areas where they were previously rare. Subsidies for installing netting to protect crops in New South Wales and reduction oflicenses to shootflying foxes have been initiated to reduce potential for bat mortality. Slow sexual maturation and low reproductive rate suggest slow population growth rate and low rates of natural mortality in adults. Increase in mortality caused by new threats puts the population at risk of severe decline because it cannot easily bounce back. While there is a lack of evidence of direct competition, Gray-headed Flying Foxes are increasingly being displaced by the Black Flying Fox and other species offlying fox, suggesting that indirect competition favors the Black Flying Fox. The Gray-headed Flying Fox occurs in some protected areas, but none of them has necessary conditions to maintain viable populations. It breeds well in captivity.

Bibliography. Andersen (1912b), Churchill (2008), Corbet & Hill (1992), Eby & Law (2008), Eby & Lunney (2002), Hsu & Benirschke (1977), Lunney et al. (2008), Ratcliffe (1932), Simmons (2005).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Pteropus poliocephalus

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2019 |

Pteropus poliocephalus

| Temminck 1825 |