Pteralopex taki, Parnaby, 2002

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6448815 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6794976 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03AD87FA-FF82-F66D-8CB2-308EFE21F70D |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Pteralopex taki |

| status |

|

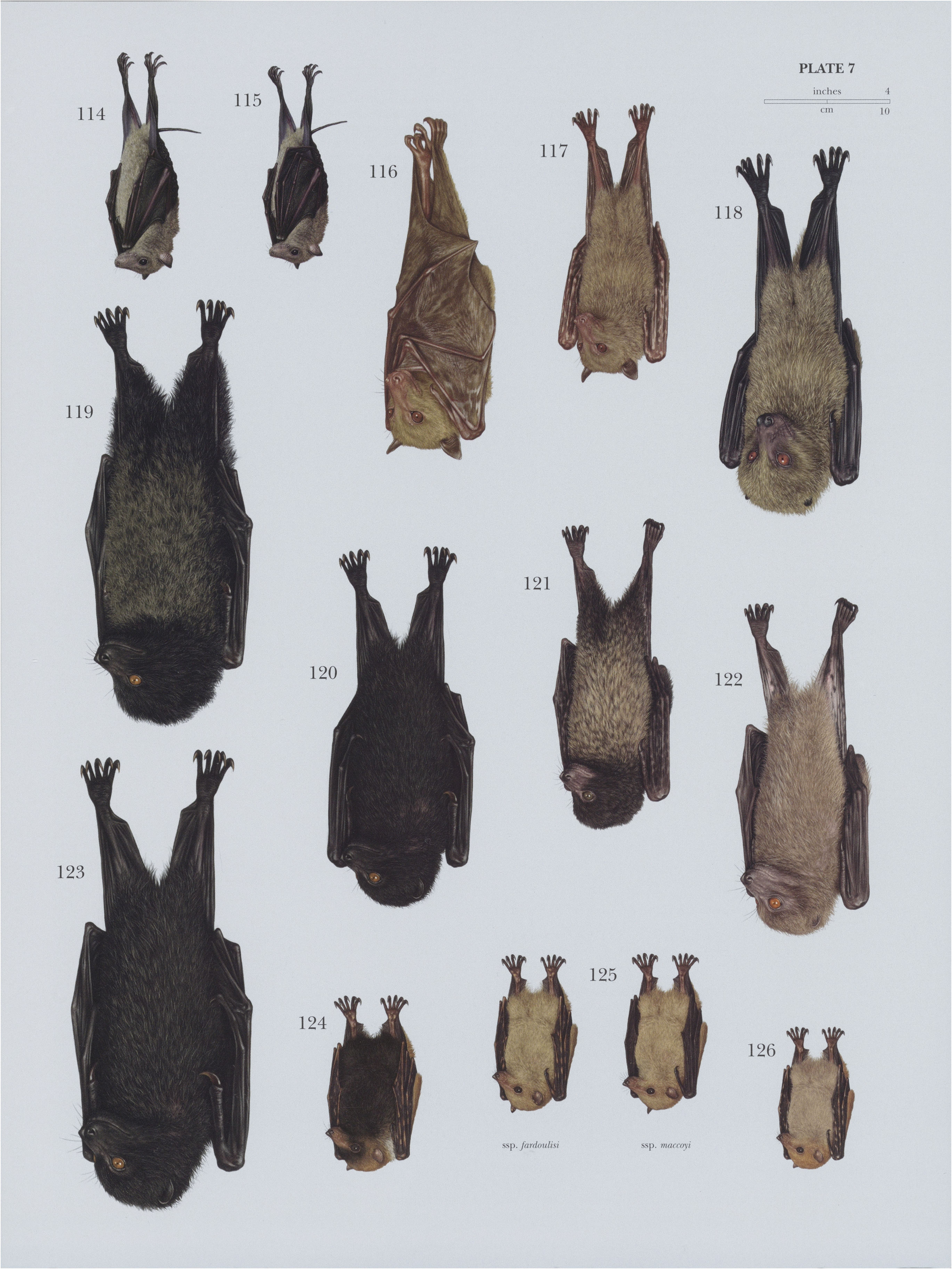

122. View Plate 7: Pteropodidae

New Georgia Monkey-faced Fruit Bat

French: Roussette de Nouvelle-Géorgie / German: New-Georgia-Affengesichtflughund / Spanish: Pteralopex de Nueva Georgia

Other common names: New Georgian Monkey-faced Fruit Bat, New Georgia Monkey-faced Bat

Taxonomy. Pteralopex taki Parnaby, 2002 View in CoL ,

*Mi Javi, 8° 31' S, 157° 52' E. 5 km north of Patutiva Village, Marovo Lagoon, New Georgia Island, Solomon Islands. Elevation ~ 50 m.” GoogleMaps

Pteralopex taki is closely related to P. pulchra and genetically distinct in 4% of loci examined. Monotypic.

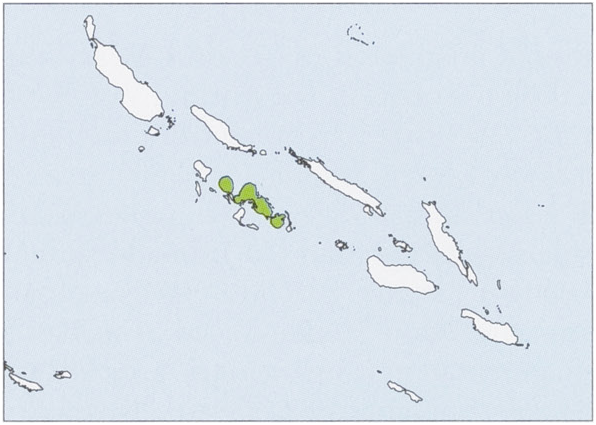

Distribution. Solomon Is (Kolombangara, New Georgia, and Vangunu). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 190 mm (tailless), ear 14-17 mm, forearm 112-123 mm; weight 225-351 g. Head of the New Georgia Monkey-faced Bat is round, with almost hairless stout muzzle; nostrils are short and divergent. Eyes are moderately large and slightly directed forward, with orange-brown irises. Ears are short, round with blunt tips, and not concealed in fur. General pelage is pale brown, grayish on head, moderately long, and soft; venter has longer and woollier pelage and is pale brown mixed with golden hairs, also on crown in some specimens. Forearm and tibia are sparsely haired. Uropatagium is very narrow, missing in center; and calcar is short. Wings are brown, with undersurfaces to a great extent depigmented, giving appearance of dark and white mottling, more intensely between body, forearm, and fifth digit but also on skin of hindlegs. Index claw is present; all claws are brown. Skull has strong basicranial deflection. Laterally, rostrum is relatively long; forehead is flat, orbit has complete ring formed by circular postorbital process annectant to thick arched zygoma; zygomatic root is above upper alveolar line, and braincase is domed. Dorsally, rostrum is relatively wide, nasals and interorbital region are narrow, postorbital foramina are tiny or missing, temporal lines join right behind orbits in obvious sharp sagittal crest, postorbital constriction is very narrow, braincase is oval, and nuchal crest is obvious. Ventrally, palate is relatively narrow, long, and flat; incisor row is arched; tooth rows are nearly parallel; postdental palate is relatively short; ectopterygoids are large; and ectotympanic is annular but wider anteriorly. Mandible is strong; symphysis is obvious; coronoid is raised and widely decurved; condyle is above sinuous lower alveolar line; and angle is rounded off, with obvious masseteric line. There are 14 palatal ridges; five are smooth, undivided anterior ridges; five more are raised, medially divided ridges; eleventh ridge is undivided;last three ridges are post-dental, close to palation; and middle and posterior ridges are denticulate. I* is larger than I' and with raised posterobasal ledges; C' is massive and long, with large secondary distal cusp and obvious lingual cingulum; P' is minute; posterior cheekteeth are squarish in occlusal outline, with strong anterior and posterior basal ledges and main labial cusp not very tall laterally and decreasing posteriorly; and M? is small. Lower dentition has minute bifid I, and very large tricuspidate L; left and right elements are almost in contact medially and have large distal basal shelf; C, is short, with large distal shelf and raised distal ledge; P, is comparatively large and tricuspidate; posterior cheekteeth are taller than canine anteriorly, decreasing in height posteriorly, with labial main ridge divided into two cusps and posterior ledge raised as a cusp in lateral view, and occlusal outline is rectangular to round posteriorly; and M,is small.

Habitat. Old growth lowland rainforests from sea level up to elevations of ¢. 400 m. Large trees are vital for the New Georgia Monkey-faced Fruit Bat. Abandoned oldvillage sites with planted native and exotic fruiting trees are suitable, even preferred foraging habitat, but they are always close to primary forest. Logged and cyclone-damaged forests are avoided.

Food and Feeding. The New Georgia Monkey-faced Fruit Bat is predominantly frugivorous, with some flowers in its diet. Fruits consumed are from trees and vines and are either white, pale green, or dark red and very soft to very tough in texture. Fruit from 18 plant species were identified in diets, and figs ( Ficus spp. , Moraceae ) are preferred. Some unripe fruits are eaten (e.g. Canarium , Burseraceae ; and Ceiba , Malvaceae ). Flowers used include Cocos (Arecaceae) , Ceiba , Barringtonia (Lecythidaceae) , and the exotic Carica (Caricaceae) . New leaves of certain trees and vines are consumed. New Georgia Monkey-faced Fruit Bats fill their cheeks with fruit, squeeze the juice, and discard dry fibrous pulp and large seeds; small-seeded fruit (seeds less than 3 mm) are eaten whole. Individuals forage alone and silently; they take fruit on the wing and fly to feeding roosts inside forests. Mixed seeds from different plant species indicate that individuals visit more than one tree each night. Strong dentition suggests use of hard food items, confirmed by pieces of bark, rotten wood, and moss in feces; skilled nut cracking was observed in one temporarily captive individual. These food items are consumed in low proportions and might be important seasonally or during food scarcity.

Breeding. Lactating and pregnant New Georgia Monkey-faced Fruit Bats and immature males and females were recorded in February—-May and a non-reproductive female in June. This suggested seasonal monoestry with reproductive activity concentrated in wet season, with one young/year.

Activity patterns. New Georgia Monkey-faced Fruit Bats are nocturnal. They leave their roost on orjust after dusk at 18:30-19:00 h, each flying in a different direction. They roost in hollows in canopies or emergent trees. Hollows are located 15-21 m high in trees averaging 26 m and typically halfway up and inside large strangler fig trees ( Ficus ) with central cavity and several entrances.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The New Georgia Monkey-faced Fruit Bat roosts in small groups; up to nine adults and dependent young have been reported. Roosts are shared with different individuals and also with other mammals (e.g. Admiralty Flying Foxes, Pteropus admiralitatum ; Dwarf Flying Foxes, P. woodfordi , or Northern Common Cuscus, Phalanger orientalis , Phalangeridae ). New Georgia Monkey-faced Fruit Bats emit a very loud, high-pitched call, sometimes repeated several times, interspersed with soft chucking, and accompanied by wing flapping that is responded to immediately by other conspecific with identical call beginning before first call had finished, suggestive of duet calling. First callers where males, with females responding on one occasion. Chattering sounds are produced in day roosts. The New Georgia Monkey-faced Fruit Bat flies under the canopy. Home range length is greater than 1 km. It was observed flying over sea between New Georgia and Vangunu, less than 1 km apart, to feed in gardens.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. The New Georgia Monkey-faced Fruit Bat has a limited extent of occurrence (less than 600 km?), its primary habitat of lowland forests is in rapid decline, and its overall population is estimated to be only ¢.400 individuals distributed on three islands very close to each other (connected during last glacial maximum), and individuals regularly move among the islands to forage. It is hunted for food but not intensely;it is vulnerable to experienced hunters who can locate roosts in conspicuous hollowed trees and by sounds occupants make during the day. Recent surveys confirmed presence of New Georgia Monkeyfaced Fruit Bats on Kolombangara Island. It does not occur in any protected area. Main threats stem from its dependence on old growth lowland rainforest that is rapidly declining due to logging, land conversion to agriculture, and effect of cyclones. Large trees lost to logging operations are a key threat.

Bibliography. Fisher & Tasker (1997), Flannery (1995a), Helgen (2005), Ingleby & Colgan (2003), Lavery (2017e), Parnaby (2002b).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Pteralopex taki

| Don E. Wilson & Russell A. Mittermeier 2019 |

Pteralopex taki

| Parnaby 2002 |