Tapirus indicus, Desmarest, 1819

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5721161 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5721177 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/039CED53-FFC4-FF88-FA50-21E814549604 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Tapirus indicus |

| status |

|

Malayan Tapir

French: Tapir de Malaisie / German: Schabrackentapir / Spanish: Tapir malayo

Other common names: Asian Tapir, Indian Tapir, Malay Tapir

Taxonomy. Tapirus indicus Desmarest, 1819 View in CoL ,

Malaysia, Malay Peninsula.

Recent studies have suggested including it in the genus Acrocordia. Considered monotypic here, although an all-black form from Sumatra was named brevetianus on the basis of two individuals.

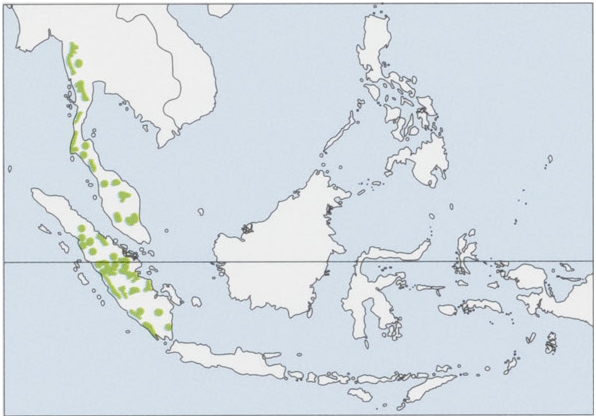

Distribution. Malayan Tapirs occur in two disjunct and isolated populations, one on mainland SE Asia in peninsular Malaysia, Thailand, and Myanmar, and the other in the S & C Sumatra, in Indonesia. View Figure

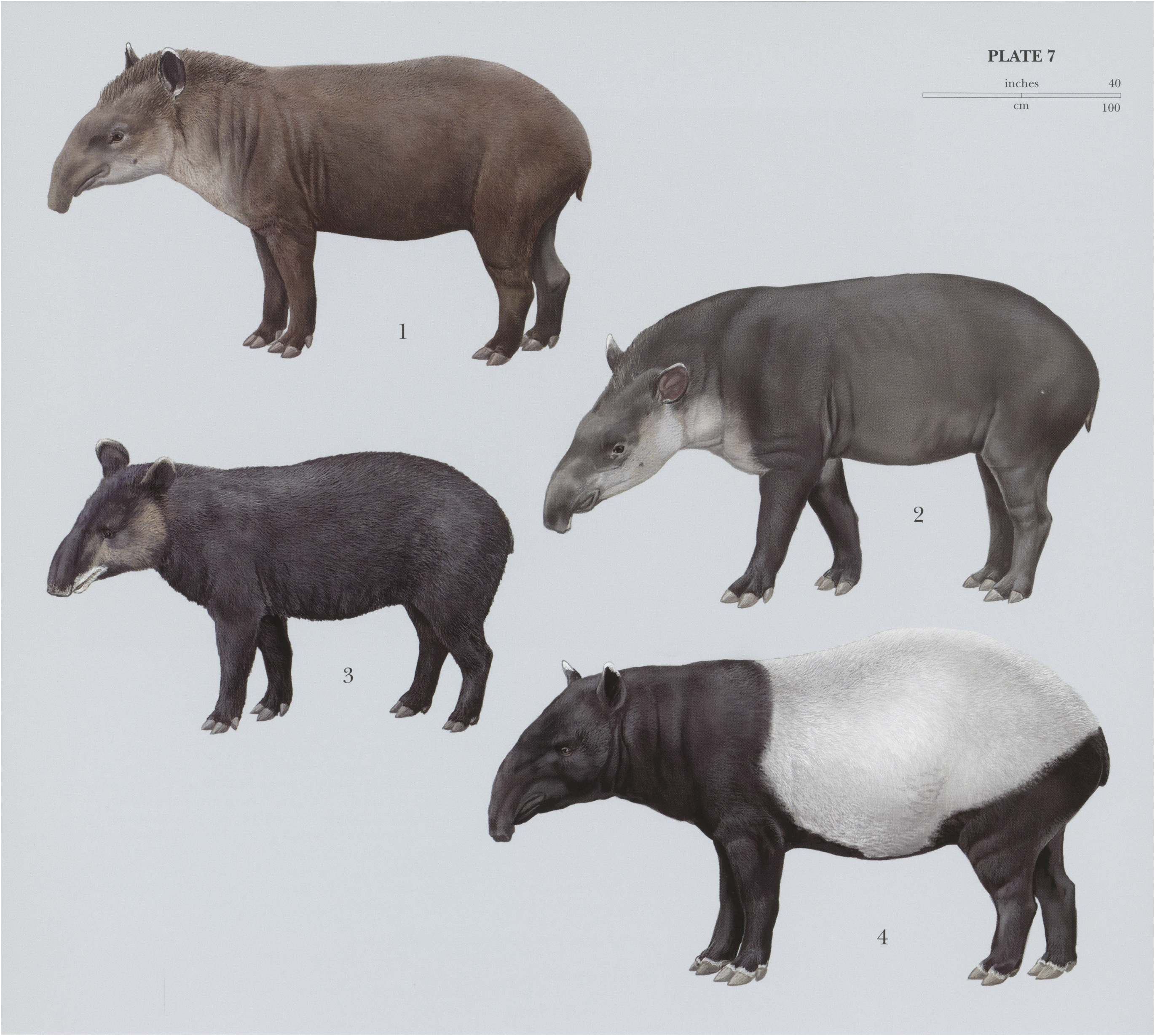

Descriptive notes. Head—body 250-300 cm, tail less than 10 cm, shoulder height 100-130 cm; weight 280-400 kg. Malayan Tapirs are the largest ofall tapir species. In fact, the Malayan Tapir is one of the largest herbivores of the South-east Asian rainforest, with only wild cattle species, rhinos, and elephants surpassing it in size. The Malayan Tapir can be easily identified by its color pattern. A white saddle starts behind the front legs and extends over the back to the tail. The contrasting colors form a disruptive pattern that blends the animal with its environment and makes it more difficult for predators to recognize it as potential prey. Completely black individuals have been photographed by camera-traps, particularly in Sumatra and Malaysia. Young Malayan Tapirs have length-wise stripes and pale spots; the white saddle only starts to show after approximately 70 days. It takes approximately 5-6 months for the last remains of the juvenilestripes to completely disappear. Although Malayan Tapirs do not have the crest seen on Lowland Tapirs, the skin on the back of the head and nape is nearly 2-3 cm thick, presumably for protection from predator fangs. It also protects the neck when the tapir is moving through dense undergrowth. The proboscis of the Malayan Tapir is longer and stronger than that of its Latin American relatives. Malayan Tapirs have a well-developed sense of smell and hearing and can move with great speed through dense undergrowth. Interestingly, it has been observed that they can escape predators by going under water and staying submerged for considerable lengths of time.

Habitat. Malayan Tapirs are found predominantly in tropical lowland moist forests and occur in both primary and mature secondary forests offering good cover. In the Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Thailand tapirs range from 100 m to 1500 m in alttude, and in Sumatra, tapirs may reach an altitude of 1500 m, or possibly 2000 m when crossing a ridge. They are not found in northern Myanmar, northern Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia,likely because of the more seasonal climate and harsher dry season of the forest in these areas. In Thailand, tapirs are associated with a variety of forest types including dry dipterocarp, mixed deciduous, dry evergreen, and hill evergreen. Tapirs move into evergreen forest during the dry season when food is scarce and forestfires are present. They return to the dry dipterocarp and mixed deciduous forest in the rainy season when sprouts of leaves and twigs emerge. Although Malayan Tapirs are generally considered to be lowland animals, they do travel a long way up mountains. In Indonesia, they inhabit lowland areas during the dry season and move to mountain areas during the wet season. Because the lowland forests are disappearing at a faster rate than the montane forests, an accelerated reduction in range and population is suspected. The Malayan Tapir habitat in Indonesia has been described as humid, swampy, densejungle with an understory of shrubby plants and grassy meadows bordering streams. In southern Sumatra, researchers found the highest densities of tapirs in undisturbed swamp areas and lowland forests on well-drained soil. The same researchers further stated that tapir densities were lower in early-stage successional forest than in late-stage successional forest that was formerly logged. Similarly, in the Jambi Province of southern Sumatra, a study showed that undisturbed areas were preferred over disturbed areas; however, signs of their presence were abundant in forest fringes as well as logged or otherwise disturbed forest, and sometimes these animals wandered into rubber and oil palm plantations. In Bengkulu, Sumatra, tapirs are considered to be a problem species for stripping bark from rubber trees. The Malaysian Department of Wildlife and National Parks (DWNP) inventories show that Malayan Tapirs are found within a 5 km radius of major cities like Seremban, Kuantan, and Temerloh. Another important aspect of their habitat use is that saltlicks apparently are visited once or twice a month, preferably with the new and the full moon. Malayan Tapirs generally stay in the vicinity of water. They like to spend a considerable time in the water and often defecate there. Several individuals have been rescued after falling into village wells or getting stuck in mud wallows.

Food and Feeding. Malayan Tapirs are selective browsers, concentrating their diet on young leaves and growing twigs. Preferred food plants mostly (42%) belong to the plant families Euphorbiaceae and Rubiaceae . Most of the plants consumed are woody and only a few herbaceous plants are consumed. In addition to foliage, Malayan Tapirs consume considerable amounts of fruit that they pick up from the ground. During feeding they sometimes push over small trees and break smaller sapling stems and branches in orderto get to the leaves and twigs. The heights at which they break stems were found to range between 0-8 m and 1-4 m. Feeding is not concentrated in particular locations. Suitable leaves and fruits appear to be eaten as encountered. Whereasit was reported by one source that their preferred food plants are characteristic of forest fringe and secondary growth, another source stated that the only feeding signs were found on understory plants in the primary rainforest. More than 115 species of plants are known to be eaten by Malayan Tapirs. Approximately 75% of these plants comprised 27 species and these are considered to be the most highly preferred food items. In Thailand, 39 species of plants were preferred. Their diet comprised 86-5% leaves, 8:1% fruit, and 5-4% leaf/twig matter. The most common plant species consumed by Malayan Tapirs in Sumatra are Symplocos, and Asplenium, Artocarpus , and Durio are occasionally eaten in secondary forests. Some herbaceous plants (Curculigo latifolia) and low-growing succulents (Homalomena and Phyllagathis rotundifolia) are also consumed, as is club moss (Selaginella willdenonii). The saplings of Baccaurea parviflora are browsed heavily.

Breeding. There is very little data about the reproduction of Malayan Tapirs in the wild. Adult females usually produce a single offspring after a gestation period of 13-14 months (390-410 days). In May 2007, a female held at the Malay Tapir Conservation Centre (MTCC) at the Sungai Dusun Wildlife Reserve in Malaysia gave birth to twin calves, one male and one female. This was the first recorded twinning in the species. To model the dynamics of Malayan Tapir populations in the wild, data from captivity have been used to estimate reproductive parameters. Captive females return to a cyclic estrus during lactation, but allow males to mount 153 days, on average, after giving birth. Mating was once observed in a captive pair on five consecutive occasions, averaging 29-4 days (range 29-31) between copulations, suggesting interestrous intervals of about 30 days. The earliest known mating ages are three years for males and average 2-8 (range 2-3-3) years for females. The earliest recorded conception by a female Malayan Tapir, at Saint Louis Zoo in the USA, occurred at 36 months, although females have mated as early as 31-32 months of age. The life span is about 30 years. A Malayan Tapir Population and Habitat Viability Assessment (PHVA) Workshop held in 2003 modelled the dynamics of Malayan Tapir populations in the wild. Considering that natural situations impose a toll on growth and achieving sexual maturity, it was assumed that in the wild both sexes are capable of reproducing for the first time at age five. Maximum age of reproduction in the wild was estimated to be 24 (+ 2) years for both sexes. The generation length of wild Malayan Tapirs was estimated to be twelve years. A female Malayan Tapir could potentially bring up some 5-15 young in her lifetime. Zoo records from the Zoo Negara, Malaysia, show birth rates with a 1:1 sex ratio.

Activity patterns. A Malayan Tapir camera-trap study in Way Kambas National Park, Sumatra, Indonesia, found the tapirs to be strictly nocturnal, with an activity pattern that peaks at 19:00 h, when their only possible predator, the Sumatran Tiger, is least active. A more recent camera-trap study in the Taratak village, West Sumatra, noted an activity peak at 22:00 h. Tapirs studied in Taman Negara in Malaysia were observed to browse occasionally during the daytime hours but were mostly encountered atrest.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. A telemetry study on Malayan Tapirs in Taman Negara, Malaysia, revealed a very large home range size of 12-75 km?.

The home range of one of the monitored males overlapped the home ranges of several other individuals. An area of 0-52 km?® was occupied over a period of 27 days, during which time the male associated with a female and her young. The average straight line distance traveled per day by a male was 0-32 km. A more recent telemetry study in Krau Wildlife Reserve, also in Malaysia, estimated a home range of approximately 10-15 km?®. One ofthe study animals moved within a range of 70 km? Malayan Tapir density estimates appear to be lower when compared to the three Latin American tapir species. In Thailand, nine individuals were observed in an area of approximately 256 km?, resulting in approximately 0-035 ind/km?In southern Sumatra, the density of tapirs has been estimated to range from 0-3 ind/km? to 0-44 ind/km? in undisturbed swamp forests and lowland forests on well-drained soil, and 0-02 ind/km? in more hilly and mountainous areas in the Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park. In Kerinci-Seblat National Park, also in Sumatra, Malayan Tapir density based on tapir signs on line-transects and camera-traps was 0-15 ind/km?. A more recent camera-trap study in the Taratak village in Sumatra resulted in a density estimate of 0-5 ind/km?. Several camera-trap studies have noted that Malayan Tapirs are predominantly solitary. A camera-trap study in Krau Wildlife Reserve revealed that they disperse substantial distances and that they visit saltlicks significantly more often than any other animal speciesin the reserve. There have been sporadic records of Malayan Tapirs crossing palm oil estates as the animals travelled from one forested area to the next.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List. The species previously was listed as occurring in northern India, southern China, southern Cambodia, and possibly southern Vietnam. There was an authenticsounding record from Laos in 1902. Further investigation of historical records and other indications from Laos, Vietnam, Cambodia, northern Thailand, and even southern China have found none that has any compelling evidence in its support. There is no credible historical-era record from north of the Thai-Malay Peninsula, although there are fossil remains from Vietnam and China that indicate a much wider range under different climatic scenarios. In Thailand, Malayan Tapirs are found along the western border, on the peninsula south to the Malaysian border, and in Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in the north. In Myanmar, the species is found restricted to the Tenasserim region, a narrow strip of territory between Thailand and the Indian Ocean.The speciesis listed as Endangered due to an ongoing population decline caused by habitat loss and fragmentation and increasing hunting pressure throughout its range. Malayan Tapirs are shy animals and appear to be highly sensitive to forest fragmentation. Population declines were estimated to have been greater than 50% in the past three generations (36 years), driven primarily by large-scale conversion of habitat to palm oil plantations and other human land-use. The rate of reduction in population is inferred to be proportional to the reduction of the tropical rainforest area in South-east Asia over the same period; however, it may be higher due to indirect threats. The population on the island of Sumatra, Indonesia, historically the main stronghold of the species,is considered to be the most endangered because of largescale habitat destruction. Approximately 60% of the forest cover of Sumatra has been lost over the past 15 years. As a consequence, more than 50% of the Malayan Tapir habitat is thought to have been lost, with much of the remaining forest either outside of protected areas or outside of the range of the species. Even in the protected areas, illegal logging continues. Less than 10% of the suitable habitat has been preserved, and much of that is degraded. In Thailand, remaining populations are isolated in protected areas and forest fragments, which are mostly discontinuous and offer little opportunity for genetic exchange. In Malaysia, forest loss is extremely severe, especially because of expanding oil palm plantations. Nevertheless, the current forestry trend seems to have stabilized at approximately 43% remaining forest cover (57% lost), of which at least half can be considered tapir habitat. In Myanmar, 3-2% of the land is protected and most tapir habitat lies outside of these protected areas. Although hunting has been a minor threat to the species in the past, it seems to be increasing as people are beginning to see the Malayan Tapir as a food source. Historically, tapirs were not hunted for subsistence or commercial trade in Thailand or Myanmar, since their flesh was considered distasteful, and some hill tribes believed that killing a tapir brings bad luck, so they are not hunted. However, some recent localized hunting has been reported in Sumatra. Nevertheless, it is uncertain how many individuals are actually hunted every year. Hunting could become a cause for concern, as already reduced and isolated populations would be at great risk for extirpation. Another problem is the removal of tapirs for zoos in Indonesia. In the past, several Indonesian zoos, especially Pekanbaru Zoo, traded in live tapirs for sale to other Indonesian zoos or private collections, or for sale as meat in local markets to the non-Muslim community. Fifty tapirs are reported to have passed through the Pekanbaru Zoo since 1993. Some of these animals are suspected of having originated from protected areas. Lastly, there have been reports of tapir road-kills in Malaysia. Further research efforts are needed to determine the total population size of Malayan Tapirs. In 2008, the population in Malaysia was estimated to be approximately 1500-2000 individuals. The speciesis legally protected in all range states and the habitat of large parts of the range is protected, including a number of National Parks in Thailand, Myanmar, Peninsular Malaysia, and Sumatra. Thailand supports one of the most comprehensive systems of protected areas in South-east Asia, comprising 17% of land area. Malayan Tapirs are recorded from forest areas in the west and south of the country, including transboundary forests in border areas and large isolated forest remnants. The transboundary forests represent the most extensive contiguous habitats for large mammals left in the country. They include the Western Forest Complex (Thai-Myanmar border), which includes twelve protected areas and covers over 18,730 km?, including both dry and wet forests, and the Kaeng Krachan/Chumpol complex, which covers 4373 km? mostly wet evergreen forest on the Thai-Myanmar border. The Balahala Forest is an expanse of 1850 km? of tropical rainforest on the Thai-Malay border. All areas are contiguous with large forest areas on opposite sides of the border. Recent survey efforts suggest that tapirs are present though uncommon in each of these transboundary forest areas. Thus, most existing Malayan Tapir habitat in Thailand is protected and the future for conservation of the species in that country is positive. In Myanmar, Malayan Tapirs are entirely restricted to rainforests in the Tenasserim Ranges along the Thai-Myanmar border. Two new protected areas have been designated in the Tenasserims, Tanintharyi National Park and Lenya River Wildlife Sanctuary. If these areas can be protected, they will preserve valuable tapir habitat in the future. Currently, civil unrest in Myanmar makes these areas inaccessible for wildlife surveys.

Bibliography. Abdul Ghani (2009), Barongi (1986, 1993), Blouch (1984), Brooks et al. (2007), CITES (2005), Duckworth et al. (1999), DWNP (2003), Ferris (1905), Fountaine (1962), Harper (1945), Holden et al. (2003), Holmes (2001), Kaewsirisuk (2001), Kawanishi (2002), Lekagul & McNeely (1988), Lynam (1996, 1999, 2000, 2003), Lynam et al. (2008), Medici (2001), Medici et al. (2003), Medway (1974), Meijaard (1998), Pournelle (1966), Prayurasiddhi et al. (1999), Read (1986), Santiapillai & Ramono (1990), Schipper et al. (2008), Steinmetz et al. (2008), Traeholt (2002), WCS (2001, 2003), Williams (1978, 1979), Williams & Petrides (1980), Yin (1993).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.