Camelus dromedarius, Linnaeus, 1758

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5719719 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5719745 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03928E69-9A4F-FFC6-D57E-FE83F6A8F649 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Camelus dromedarius |

| status |

|

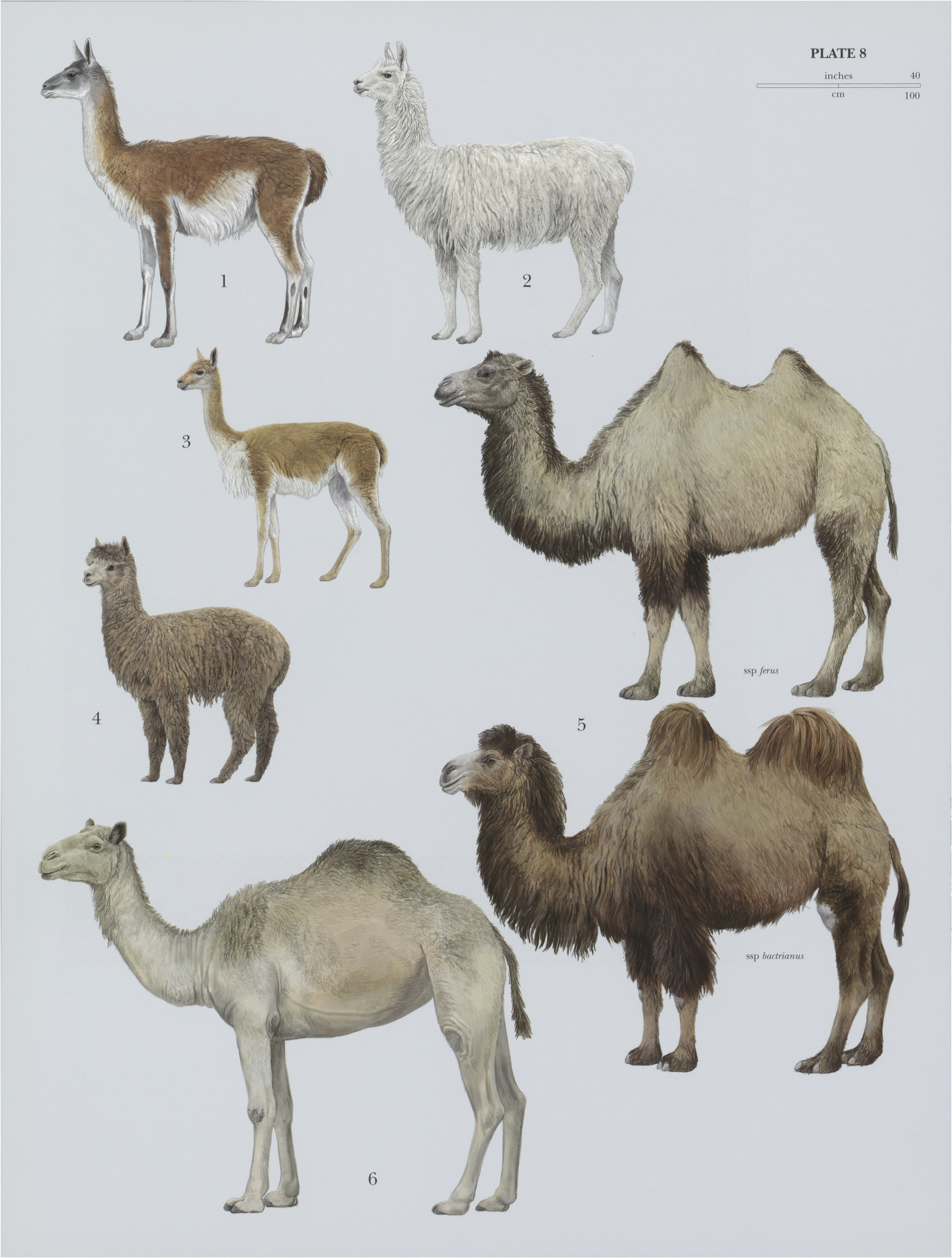

6 View On .

Dromedary Camel

Camelus dromedarius View in CoL

French: Dromadaire / German: Dromedar / Spanish: Dromedario

Other common names: Camel, Arabian Camel, One-Humped Camel, Single-Humped Camel, Ship of the Desert

Taxonomy. Camelus dromedarius Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL ,

“Habitat in Africae desertis arenosis siticulosis.” Restricted to “deserts of Libya and Arabia” by Thomas in 1911.

This species is monotypic.

Distribution. A species found in the arid and semi-arid regions of N Africa to the Middle East, and parts of C Asia. A sizeabledfreeranging/feral population in C&W Australia. The Dromedary overlaps with the domestic Bactrian Camel (C. bactrianus ) in Turkey, Afghanistan, Iran, India, Kazakhstan, and Turkmenistan. Dromedaries are a domestic species with c¢.50 breeds selected and used for pulling carts, plowing, lifting water at wells, carrying packs, milk production, smooth riding, and racing. The breeds include those in Saudi Arabia (Mojaheem, Maghateer, Wadah, and Awarik), India (Bikaneri, Jaisalmeri, Kachchhi, and Mewari), Pakistan (Marecha, Dhatti, Larri, Kohi, Campbelpuri, and Sakrai), and Turkmenistan (Arvana). The evidence for domestication comes from archaeological sites dating ¢.4000-5000 years ago in the S Arabian Peninsula with the wild form becoming extinct ¢.2000-5000 years ago. No non-introduced wild populations exist. In Asia Dromedaries occur from Turkey to W India and N to Kazahkstan. All camels in Africa are Dromedaries, 80-85% in the Sahel and NE portion of the continent ( Somalia, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Kenya), with the S distribution limited by humidity and trypanosomiasis. Dromedaries in S Africa show no evidence of loss of genetic diversity within 16 populations and very low differentiation among populations. In Kenyan Dromedaries two separate genetic entities have been identified: the Somali and a group including the Gabbra, Rendille, and Turkana populations. In India two distinct genetic clusters have been described for Dromedaries: the Mewari breed being differentiated from the Bikaneri, Kutchi, and the Jaisalmeri breeds. From the 17" to the early 20" century unsuccessful attempts were made to introduce Dromedaries to the Caribbean, Bolivia, Peru, Colombia, Brazil, Namibia, and south-western USA. Successful introductions of camels were made to the Canary Islands in 1405 and some 10,000 to Australia from 1840 to 1907. Camels were important for exploring and developing the Outback of C&W Australia, where they were used for riding; drafting; transporting supplies, railway, and telegraph materials; and as a source of meat and wool. Most (6600) introduced Dromedaries came from India. Three breeds were originally introduced: camels for riding from Rajasthan, India, camels for heavy work from the Kandahar region of Afghanistan, and camels for riding and carrying moderate cargo loads from Sind, Pakistan. The camels in Australia today are a blend of these original imports. By the 1920s, there were an estimated 20,000 domesticated camels in Australia, but by 1930, with the arrival of rail and motor transportation, camels were no longer needed and many were released to the wild. Well suited to the Australian deserts, the camels bred prolifically, spreading across arid and semi-arid areas of the Northern Territory, Western Australia, South Australia, and into parts of Queensland, and today they occupy 37% of the continent. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 220-340 cm, tail 45-55 cm, shoulder height 180-200 cm; weight 400-600 kg. Males and females of near equal size, but in some breeds the females are ¢.10% smaller than males. Body is often sandy colored, but can range from nearly all white to black or even two-colored piebald. Body shape characterized by a long-curved neck, long and thin legs, and deep narrow chest. The hindquarters are less developed than the weight-bearing front legs. Large eyes are protected by prominent supraorbital ridges. Facial features include thick eyebrows, long eyelashes, and transparent eyelids that allow partial vision when the eyes close in sandstorms. Thick fine hair in winter for warmth sheds in summer. Hair is longer on throat, shoulder, and hump. The single hump, on the middle of the back (c. 20 cm higher than shoulder)is a reservoir offatty cells bound by fibroustissues, used in times of food and water scarcity. Hump size varies, depending upon an individual's nutritional status. In a state of starvation, the hump can be almost non-existent. The head is small relative to body size. Slit-like nostrils, surrounded by sphincter muscles, can close to keep out dust and sand. Split upperlip with two independently moving halves and a pendulous lowerlip allow for prehensile-like grasping of forage. Upper middle and inner incisors are replaced by a tough dental pad that opposes the lower incisors. Canines, especially the upper, are massive and pointed. Skin is tightly attached to underlying tissues and modified into horny pads at the sternum, elbows, carpals,stifles, and tarsals: these protect the body when a camelis lying down on hot or rough ground. No facial glands, but males have well-developed occipital glands 5-6 cm below the nuchal crest on either side of the neck midline. The glands increase in size with age, and during the rut they secrete a pungent coffee-colored fluid. Small oval erythrocytes may enhance blood circulation and oxygen carrying capacity. Dromedaries are digitgrade each with two dorsal nails and padded feet well adapted for sandy substrates; the front feet are larger than the hindfeet. The mammary gland has four quarters and teats. Adult dental formula: 11/3,C1/1,P 3/2, M 3/3 (x2) = 32 with permanent lower incisors appearing at 2:5—6-5 years and all teeth emerged by eight years. A triangular bone ¢.3 x 2: 5 cm is lodged in the tendinous fibers in the center of the diaphragm, preventing compression of the interior vena cava and distributing muscular pull over a larger surface. Lungs are not lobed. The stomach is complex, with three compartments. When foraging on green and moist plants Dromedaries do not require drinking water. If wateris available in summer, they will drink regularly at dawn. In extreme drought, they need access to waterholes. The Dromedary’s ability to endure severe heat and dryness does not depend upon water storage; instead, numerous mechanisms minimize water loss. In well-watered animals body temperature fluctuates only c.2°C. When necessary, water conservation is aided by heat storage (hyperthermia): camels do not sweat until body temperature exceeds 41-42°C, thus avoiding water loss through perspiration. The body temperature of camels deprived of water can fluctuate as much as 6°C by heating up during the day to 41°C and then cooling at night to 35°C. Dehydrated Dromedaries have a depressed rate of breathing, minimizing water loss through respiration. Paired, fluid-producing sacs connecting the nasal cavities and a pair of lateral nasal glands and sacs serve to moisten incoming dry air. Dromedaries can tolerate water loss greater than 30% of their body mass, whereas 15% lossis lethal for most mammals. Such water loss is from intraand intercellular fluids, and not from plasma, allowing for relatively constant circulation of blood and maintaining the ability to cool. Water loss is ¢.50% greater in shorn compared to unshorn camels. Dromedaries often go without water in the Sahara Desert for seven or eight months, beginning in October, existing only on water content of plants. At temperatures between 30°C and 50°C they can go without water for 10-15 days, and even in the hottest weather need water only every 4-7 days. They can quickly rehydrate by drinking large quantities of water (10-20 1/minute and up to 130 1/minute), consuming up to 30% of their body weight within minutes. Dromedaries can drink salt water in even greater concentrations than seawater. They can consume water containing 19,000 ppm (parts-per-million) in dissolved salt without a decline in condition, compared to sheep, which can consume water at 10,000 ppm and cattle 5000 ppm. Dehydrated camels excrete less fecal water, greatly reduce urine volume, highly increase urine concentration, and recycle urea from the kidneys to the rumen for protein synthesis and water recirculation. Their erythrocytes have high osmotic resistance and can swell to 240% of their initial size without hemolysis during rehydration. Accumulation of fat in the hump instead of subcutaneously facilitates heat dissipation. The gallbladderis absent. The dulla, a pink, tongue-like bladder that hangs out the side of mouth of rutting-agitated males,is actually an inflation ofthe soft palate and unique to Dromedaries. Dulla inflation is typically accompanied by large amounts of saliva foam and gurgling vocalization.

Habitat. In Africa Dromedaries occupy the Sahara Desert, known forits long, hot-dry season and a short rainy season. In Australia, Dromedaries favor bushy semi-arid lands and sand plains because of the availability of year-round forage, and avoid heavily vegetated and hard rocky areas.

Food and Feeding. Dromedaries are capable of surviving on poor-quality forage under arid conditions, aided by their ability to select high-quality plant species, increase digestion of low-quality forage, cover large distances while foraging, and diversify the nature of their diet by being both browsers (shrubs and trees) and grazers (forbs and grasses). In the Sahara browse and forbs make up 70% oftheir diet in winter and 90% in summer. Over 300 forage plants have been reported, with Acacia, Atriplex, and Salsola common in their diet. In Syria shrubs dominated the diet during the dry season, but camels switched mainly to herbaceous species with the onset of the wet season. In Australian deserts food intake by volume is 53% browse, 42% forbs, and 5% grasses. Dromedaries browse on trees and tall shrubs up to 3-5 m by grasping with their lips and either breaking off branches or stripping leaves. Under extreme cases of limited forage, the Dromedary can not only decrease its food intake, but also reduce its metabolic rate. Compared to sheep and cattle, Dromedaries require less energy for maintenance; their protein requirements are at least 30% lower than cattle, sheep, or goats. Feeding trials have revealed that Dromedaries utilized fed energy for maintenance with an efficiency of 73% comparable to sheep, and for growth with an efficiency of 61% better than sheep and cattle. The relationship of food intake to body size is low. They can live on only 2 kg of dry matter for limited periods, and 8-12 kg are sufficient for a working Dromedary carrying 130-227 kg load for six hours a day at a speed of 5 km /h for a 24day trip. When forage conditions are lush, camels tend to overeat for their immediate needs and store the excess energy in their humps. Dromedaries require six to eight times more salt than other animals, with 30% oftheir diet from halophytes (plants that tolerate and even require salty conditions). High salt intake is imperative for alimentary absorption of water by camels, with salt deficiencies leading to cramps and cutaneous necrosis. Although consumption of grain can cause indigestion in animals unaccustomed to it, working Dromedaries require 2 kg of grain per day.

Breeding. The breeding season is variable depending upon latitude and climate patterns. Dromedaries typically breed in winter, except near the Equator, where there can be two mating seasons or even year-round mating. In the Arabian camel, sexual receptivity is triggered by rainfall and subsequent availability of forage. There is follicular activity in the female year-round, but it peaks in winter and spring. Mating induces ovulation, which occurs 30-40 hours afterwards; estrus ceases three days later. An unmated female's cycle averages 28 days;follicles mature within six days, are maintained for 13 days, and regress over eight days. The percentage of females that conceived: 50% after a single copulation, 30% after two, and 20% after three or more, during the first two days of estrus. Left and right ovaries are equally active and alternate in follicle production. Egg migration is common, 50% of left-horn implants form corpora lutea in the right ovary, explaining the long oviductal transport time of six days. Simultaneous ovulation from both ovaries occurs 14% of time, but twin pregnancies only 0-4%. The left horn of the uterus is larger than the right and carries 99% of pregnancies. Normal pregnancy produces one offspring, with twins being extremely unusual. The scrotum is high in the perineal region with testes larger during rut. Penis is covered with a triangular sheath opening pointing posteriorally and directed between the hindlegs. A complete separation of the penis from preputial adhesions prevents erections at 6-10 months before sexual maturity. Female lies down in sternal recumbency during copulations averaging 8-120 minutes involving 3-5 ejaculatory pulses by the male, each stimulated by intracervical pressure on his highly mobile urethral process. Mating females normally ruminate; the male may salivate, inflate his dulla, or gurgle during mating. Gestation averages 377-390 days (range of 360-411 days), regardless of whether the calf is male or female. The typical calving interval is 2-3 years (two in Australia), with estrus occurring 4-5—-10 months after parturition. The mean birth massis 37-3 kg (26-4-52-3) with no difference between sexes. Annual calving rates are low (35-40%) because of high (18-20%) embryonic death, abortions, and stillborns. In free-ranging herds, young remain with their mothers for first two years. Males begin rutting at three years but are not fully active sexually until they are 6-8 years old. They continue to breed until 18-20 years of age. Females are sexually mature at three years and typically first mate at 4-5 years and reproduce until they are 20-25, and some until the age of 30. Puberty is delayed by inadequate body weight caused by insufficient food. Birthing duration is typically 30 minutes, with the female in a sitting position. The mother noses and nibbles, but does not lick her newborn. The main birth season in Australia is June to November, during the rut, but newborns have been observed year-round. Before parturition cows segregate themselves (without their previous twoyear-old calf) from their original group and give birth in seclusion in dense vegetation. Isolation thought to be both an anti-predator behavior and perhaps more significantly, avoidance of infanticide by rutting males. After remaining alone for up to three weeks, when the new calf is fully mobile, the female joins other recent new mothers, forming a new cow group. These core groups remain stable until the calves are weaned at 15-18 months, the length of time depending on environmental conditions. Life span of wild/feral animals is 20-35 years. Domestic Dromedaries live substantially longer, with reported maximum longevity 40-49 years. The first cloned camelid was a Dromedary Camel achieved in 2010 by use of somatic cell nuclear transfer.

Activity patterns. Wild/feral populations exist only in Australia, where they show a daily pattern of feeding in the morning and afternoon hours and increased resting in the middle of the day. Midday resting is highest in winter. Elsewhere Dromedaries are domestic and intensely managed and regulated by traditional pastoral communities, often in conjunction with other livestock. In the Sahara, when they are allowed to roam without herders, they form stable groups of 2-20 animals. Dromedaries graze for 8-12 hours per day and then ruminate for an equal amount of time. When forage is especially poor they spread out over large areas and break up into units of 1-2 individuals. Guarded herds feed by day (lying down during the hottest hours) and rest by night, but unguarded, their activity pattern is reversed.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Dromedaries are extremely mobile and capable of using large areas to fulfill their nutritional needs. Depending upon environmental and social parameters, wild/feral populations of Australia may be nomadic, migratory, or move within a home range. They commonly travel 30 km /day even when food is plentiful. In summer, when plants are dry, they comfortably walk up to 60 km to waterholes every second or third day; in winter they drink water only irregularly, some once per month, others less often. In free-ranging Australian populations, social groups are core cow groups, breeding groups, male groups, and solitary males. Core cow groups occur only in summer (October to March/April) outside the breeding season. These groups of about 24 animals consist of females and their calves of similar age; the groups are stable for up to 1-5-2 years until the young are weaned. Summer cow groups are open to all other individuals (cows with and without calves, including younger and weaker adult males). Individuals join for irregular periods of time. Breeding groups are seen in winter (April/May to September). They are composed of one mature male and several cows with their calves; the male defends the females against other males in a classical harem arrangement. Soon after taking over a cow group the rutting male aggressively chases away weaned two-year-old males; these young males join male groups. The rutting male herds cows for 3-5 months, leaves voluntarily, and does not return to the same cow group the following year; thus the rutting male is never the father of the calves in his group. Male or bachelor groups of up to 30 non-breeding males of all ages are present year-round. These are loose groupings that regularly split up as individuals leave the group and join other males. Solitary males tend to be old males. A rutting male shows ritualized postures and patterns, including vigorous biting when fighting with and defending his breeding group against other males. It should be noted that aggressive spitting, as observed in Bactrians and the South American cameloids has not been observed in Australian Dromedaries. However, Dromedaries may vomit when severely frightened or overly excited. Night time hypothermia in a rutting male may increase the duration and success of his daytime fighting before the male overheats. No classical territoriality has been observed in Australia, but short-term home ranges of 50-150 km* and an annual range, commonly of 5000 km?, shows a tendency forsite attachment to home ranges. Dromedaries show amazing plasticity of social organization with extremes in environmental conditions. During two years of extremely high rainfall in the Australian Outback when food productivity was extraordinarily high, animals coalesced into large herds of up to 200. During the rutting season the herd was subdivided into several breeding groups, each with one herding male, all roaming around together. The subgroup holders tolerated each other to a certain point within the big herd and even showed some cooperation in defending their cows when intruding bachelors came too close. However, during two years of virtually no rainfall (although water was always available for drinking) when food became acutely sparse, normal cow groups split up, even to the extreme of only one mother with her calf. In such harsh droughts conspecifics became each other’s strongest competitors. A social system similar to that seen in Australia occurs in Africa at Equatorial latitudes, except the non-breeding season is in winter. Mixed herds (males and females of all age classes), some as large as 500 camels, are more common. In Algeria domestic herds were much less rigid: 46% of the herds were males, females, and young; 21% males and females without young; 18% females and young; and 14% males only. In Turkmenistan domestic populations were divided into the social units similar to those in Australia. In breeding groups of wildferal populations the male directs the movements of his group from behind, while females rotate in the lead. Domestic herds have a natural tendency to walk in single file, especially when moving to water wells. Dromedaries do not use dung piles for defecation or urination. Freeranging camels showed no marking behavior in the Sahara, but males in Israel mark particular areas with poll-gland secretions. They like to roll in sandy locations and will form lines waiting their turn.

Status and Conservation. World Dromedary population decreased 15% from 1960 to 2000, with current numbers 18-21 million, including one million camels in Australia. In some countries the decline has been severe over the last century; for example in Syria the population decreased from 250,000 in 1922 to not more than 22,000 in 2010. In Australia Dromedary competition with livestock for forage and water, and significant environmental and infrastructure damage caused by Dromedaries, have prompted culling, with the goal of maintaining a sustainable population for utilization of their meat, hides, and wool. Despite groups of Dromedaries seen moving and grazing without a herder in the Sahara and Arabian deserts, they all have owners. Numbers have drastically declined in Arabian countries during past half century due to modernization and industrialization, forced settlement of nomads, desert forage resources not well developed, low reproductive rate, decreased demand for camel meat and milk, poor genetic selection for breed improvement, and government encouragement of other domestic species.

Bibliography. Al-Ani (2004), Arnautovic & Abdel-Magid (1974), Baker (1964), Baskin (1974), Bhargava et al. (1963), Dagg (1974), Dorges et al. (1995, 2003), EI-Amin (1984), Ellard (2000), Gee & Greenfield (2007), Gidad & El-Bovevy (1992), Grigg et al. (1995), Guerouali & Wardeh (1998), Guerouali & Zine Filali (1992), Gauthier-Pilters (1984), Gauthier-Pilters & Dagg (1981), Klingel (1985), Kohler-Rollefson (1991). McKnight (1969), Mehta et al. (1962), Newman (1984), Novoa (1970), Peters (1997a) Peters & von den Driesch (1997b), Saalfeld & Edwards (2008), Schmidt-Nielsen, B. et al. (1956), Schmidth-Nielsen, K. (1964), Schmidt-Nielsen, K. et al. (1967), Singh, U.B. & Bharadwaj (1978), Singh, V. & Prakash (1964), Wilson (1984), Yagil (1985).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.