Vicugna pacos (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5719719 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5719739 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03928E69-9A44-FFC1-D0A7-FD9EF7A7FE66 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Vicugna pacos |

| status |

|

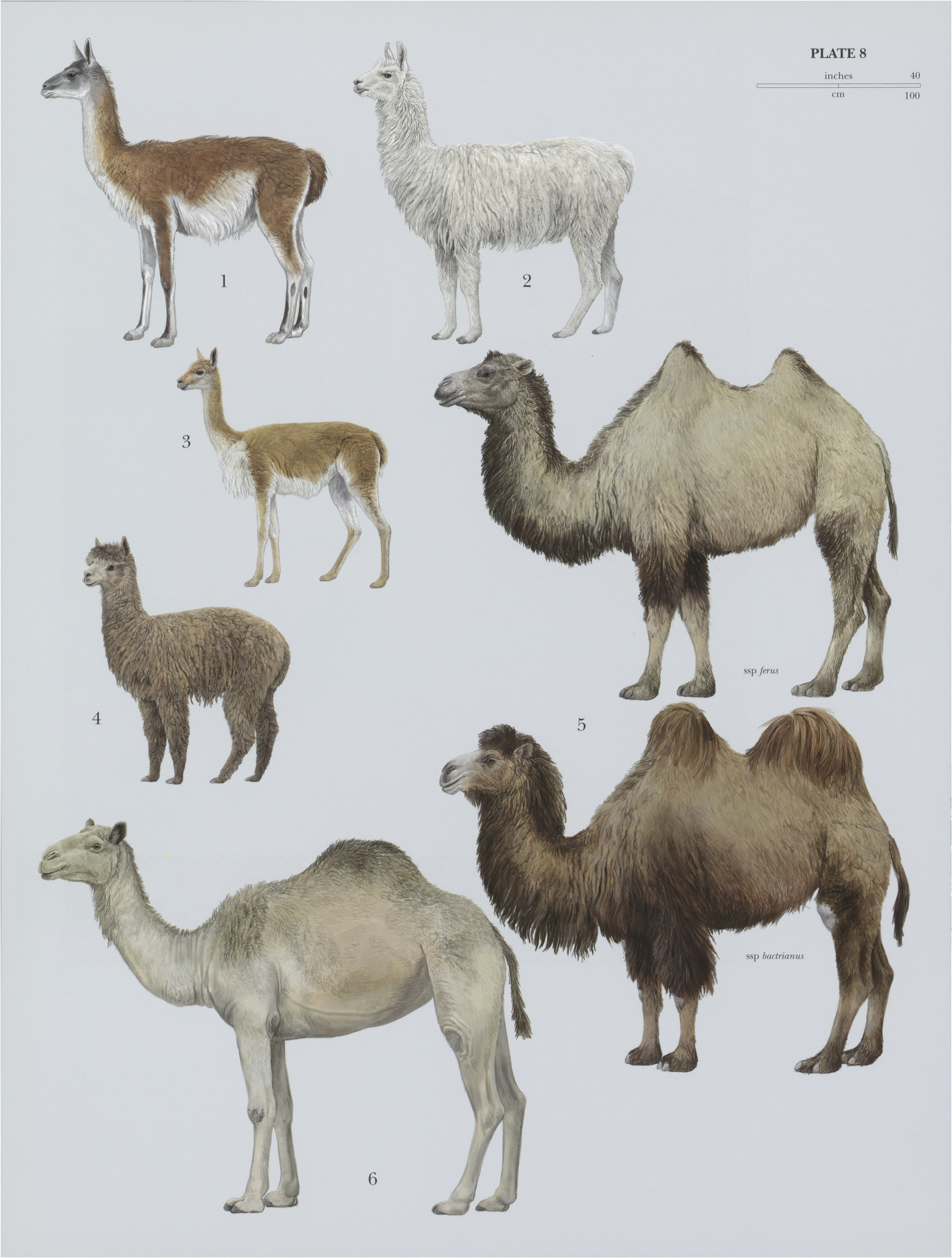

4 View On .

Alpaca

French: Alpaca / German: Alpaka / Spanish: Alpaca

Taxonomy. Camelus pacos Linnaeus, 1758 ,

Peru.

The Alpaca is a domesticated camelid indigenous and endemic to South America, well known for the characteristics of its fine-diameter wool: soft, silky, high luster, lightweight, and warm. Alpaca woolis used for luxurious blankets, sweaters, and cloth. The species was long classified in the genus Lama , but recent DNA studies (mtDNA sequences and nuclear microsatellite markers) have established that the Alpaca was domesticated from the Vicuna subspecies V. vicugna mensalis, showing significant genetic differentiation to warrant a change in its genus to Vicugna and its designation as a separate species. Archeological digs at the Telarmachay site in the Central Andes of Peru indicate that the Alpaca was domesticated 5500-6500 years ago by a hunter-gatherer society. These early indigenous herders selected for an animal with a docile nature while maintaining the fineness of its progenitor’s wool. No remains of Alpaca have been found to date at archeological digs in the south of Central Andes (northern Chile and north-western Argentina), but only early domesticated Llamas ( Lama glama ). The Alpaca has no subspecies, but two distinct breeds are recognized: the Huacaya and Suri.

Distribution. Alpacas are found in the Central Andes from C Peru into mid-Bolivia and N Chile. In the 1980s—1990s Alpacas were imported into the USA, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Europe. There are no known wild/feral populations of Alpacas. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 114-150 cm,tail 18-25 cm, shoulder height 85-90 cm; weight 55-65 kg. Alpacas have long necks; relatively short, straight ears (c. 15 cm), thin and agile legs, and fluffy-appearing bodies because of their long wool. When shorn, however, the bodyis slender and Vicuna-like. There are two distinct breeds. HUACAYA ALPACA: Huacayas are the more common (¢.90%) of the two breeds. Its body, legs, and neck are covered by wool that is long, fine (27-5 microns), and wavy; the head and feet are covered by short wool. Wool grows 5-15 cm/year depending upon nutrition and decreases with age. Huacaya wool is crimped (regular and successive undulations) and similar in appearance to Corriedale sheep wool. Huacayas are bigger in size, have shorter and relatively coarser wool, and lighter fleeces than Suris. There are three general categories of wool: “Baby Alpaca” (20-23 microns some as low as 16-17 microns)is the finest and most expensive wool from recently born animals; “Tui” wool is from the first shearing at 12-18 months; and “Standard” Alpaca wool (c.24 microns) is from animals of two years of age and older. White Huacayas are the most common (c.80%), especially on large commercial Alpaca ranches, compared to 30% white animals in indigenous flocks. White wool accounts for over 80% of the total annual Alpaca wool production. Although most Alpaca wool has little cortex in its fibers,it can be easily dyed just as sheep wool, giving woollen mills greater flexibility with white Alpaca wool. Huacaya Alpaca crossed with a Vicuna produces a Paco-Vicuna, which resembles a large-bodied Vicuna and has 17-19 micron wool. Resource managers are concerned that accidently escaped Paco-Vicunas could have harmful genetic consequences on populations of pure Vicunas. SURI ALPACA: Suris arise from a very small percentage (2%) of Huacaya x Huacaya crosses, thus the origin of the breed. Because of their long-hanging wool, phenotyically Suris are quite distinct from Huacayas. Suri wool is silky (24-27 microns), straight, without crimp, generally finer, longer, more lustrous, softer to the touch, less elastic, less resistant to tension, and faster-growing compared to the Huacaya. The wool parts on the animal’s back create a mid-body line that is capable of growing up to 15 cm /year. Some individual Suris, called “wasis” by Andean herders, are not shorn for years, resulting in the fleece growing until it touches the ground; only a few such special animals are kept and are revered by the indigenous people. Around 17% of the offspring from Suri x Suri crosses produce Huacaya types. In their South American homeland, Suri Alpacas are considered to be longerlived, more delicate, less hardy, and to have lower fertility than Huacaya Alpacas. Recent research has found thatjuvenile mortality is high because of lack of wool coverage on the midline. However, when given the right management and equally good pastures, they thrivejust as well and with similar fertility as Huacayas. During lactation Suri Alpacas lose weight more than Huacayas because they produce more milk (udders are larger on Suri females). As a result, Suri young are heavier than Huacayas because they have a greater availability of milk. Body wool is uniform or multicolored; 22 natural colors have been categorized, ranging from white to black, with intermediate shades of grays, fawns, and browns. The upperlip is split for grasping forage. The eyes are large, round, and slightly forward looking. The feet have soft-padded soles and two toes, each ending with large pointed nails. Testes are small, oval-shaped and located in the perineal region under the tail. Life span is 15-20 years. The cuticle on individual wool fibers is made up of poorly developed, elongated, and flattened cells. While such rudimentary cuticle scales without ridges results in poor felting qualities, it makes the Alpaca wool extraordinarily smooth and soft to the touch. Still, Alpaca wool is 3-6 times stronger than human hair. Based upon strand diameter and morphology, the fleece (pelt) of this ungulate is made up of two types of hair: wool and hair. Similar to fine sheep wool, the medulla can be non-existent in unusually fine Alpaca wool, but has been observed in Peruvian Alpaca fibers averaging 17 microns. Such pure Alpacas are considered “one coated” because their fleece consists only of the fine undercoat hairs and lack the outer coarser guard hairs. As the proportion of medullation increases (as it does with age), wool diameter increases and fineness decreases, thatis, the proportion of the medulla progressively increases with the thickness of the individual wool strand. Woolis of the cortex type of fineness, and hair is of the medullar type with larger diameter. Hair is especially common on the chest, face, and extremities, but it is not unusual to find individual hairs intermixed throughout the fleece. This is especially common in “Huarizos,” hybrids between an Alpaca female and a Llama male. Huarizos show intermediate physical characteristics of the two parents, and relatively coarse wool (c.32 microns in diameter). Their fleeces contain as much as 40% guard hair. Huarizos are considered undesirable by the Alpaca wool industry and are being selected against on commercial Alpaca farms. Nearly all (90%) Alpacas on large farms are shorn annually and done indoors with shearing scissors or by mechanized clippers. In indigenous family herds in the Andes only half of the animals are shorn each year, and done under rustic conditions in the out-of-doors with hand shears. Shearing of males, geldings, non-pregnant and some pregnant females takes place in November and December, while new mothers with young, yearlings, and thin males and females are done in February to April. Annual shearing yields 1.5-2. 8 kg of wool per Alpaca in South America (enough to make four sweaters), and up to 3-6 kg in USA and Australia. Fineness of Alpaca fleeces vary from farm to farm in Peru (24-7-32-3 microns, averaging 28-9 microns), but in other countries where it has been introduced, 16-24 microns is more typical. In the Andes Alpaca wool increases in diameter from 17-4 microns to 27-5 microns from the first shearing at ten months to six years of age. Large Alpaca farms in Peru are able to practice better husbandry through pasture management, selective breeding, and health care. Of 3762 shorn Alpacas on one such farm in Puno, Peru, in the 1980s, wool was sorted and classified into the following five quality categories: X 3% at 19 microns, AA 52% at 25 microns, A 17% at 37 microns, LP 23% at 44 microns, and K 5% at 49 microns. Still, nearly half was considered “thick” relative to the Alpaca’s potential for producing fine wool. Now, two decadeslater, better management and selection is beginning to improve wool quality. Alpaca wool production and quality is strongly influenced by artificial selection (genetics) and nutrition. Seasonally wool production varies under the extreme conditions of the Alpaca’s high-altitude habitat: fiber or strand length has been shown to be 25% longer during the rainy season in the Andean highlands, reflecting the percentage of crude plant protein that decreases from 11% in the wet season to 3-5% in the dry season. Wool quality decreases (increase in diameter) when Alpacas are grazed on high-quality pasture compared to native range of poor to very poor quality. For example during a 15month feeding trial relative to controls, Alpacas on diets in Andean rangeland vs. managed pastures of alfalfa, increased the body weight of mothers and young 10 kg and 22 kg respectively, fleece weight 0-4 kg and 0-8 kg, staple length 2-3 cm and 1-8 cm, fiber diameter 5-2 microns and 6-9 microns, and yield 4-1% and 10-8%. In another study adult Alpacas on high-feeding regimes resulted in increased stand diameter (fine 21-22 microns to thick 27-28 microns), but wool production per head/year increased from 1-1 kg to 2-4 kg. But, because there is little commercial difference in value per kilogram in the two wool diameters, total monetary value was doubled on the higher feeding regime. Contrary to the long-time belief that Alpacas produce finer wool at higher elevations in the Andes, recent studies with controls have shown that when on the same diet wool quality was similar. Commercially, the majority of Alpaca wool is made into carded and semi-carded thread. In the textile industry it is often blended with merino sheep wool to be made into overcoats and high-fashion knitwear. In general, Alpaca wool quality in the Andes is lower than its potential due to poor management and the extensive Alpaca/ILlama hybridization that has occurred over the past 400 years since Spanish colonization. DNA studies have revealed that today’s Andean Alpaca population shows a high (80-92%) level of hybridization. Along with a significant reduction in Peru’s Alpaca population during colonization, pure colored animals significantly decreased to the point that they became rare. The difference between Alpaca and Llamas and between Huacaya and Suri Alpacas has also been impacted. Alpaca husbandry is now addressing these problems. Additionally, in the 1970s the Alpaca population in Peru dropped resulting in a 40% decline of wool production due to land and agrarian reforms. A number of revealing physiological parameters have been measured in Alpaca. Body temperature of normal adult males (n = 50) and females (n = 50) is the same (38-7°C), pulse rate/minute in males (83-2 + 2-2) is higher than females (76:6 + 1-9), and respiration rate/minute is similar for males (29-2 + 1-1) and females (28-3 + 0-79). For young Alpaca 10-12 months old (n = 50) body temperature is 38-5 + 0-04, pulse rate 83-8 + 2-9, and respiration rate 33-1 + 0-19. For femalesin the last days of gestation body temperature (38-3 + 0-07) is the same as non-pregnant females, but pulse rates (83-5 + 2-3), and respiration rates (34-8 + 1-9) were higher.

Habitat. Alpacas are raised in the Andean highlands; regionally known as the Altiplano and Puna. The Puna ecosystem is rolling grassland and isolated wetlands typically at c.3500-5200 m altitude with two marked periods: the rainy season from October to April and the dry season from May to September. Most (75%) precipitation falls from November to March in the form of both hail and rain. In Peru the annual precipitation varies from 800 mm in the south to 1200 mm in the central mountains. The mean annual temperatures are less than 10°C and nocturnal frosts are common, especially during the dry season. Diurnal fluctuations can be as much as 20°C in the mesic Altiplano and even greater in the dry or desert Altiplano. The short growing season, as determined by moisture and night-time cloud cover, occurs between December and March. Vegetation is dominated by herbaceous grasses and forbs. Few trees exist and shrubs are only locally abundant. Perennial bunchgrasses are common including the genera Festuca , Poa , Stipa , and Calamagrostis , as well as the grass-like sedges Carex and Scirpus . High-quality forage is more abundant during the rainy season and scarcer during the remainder of the year. A critical habitat and principal source of forage for Alpacas in the Andes that allows intensive-localized foraging are bofedales or mojadales. Providing lush forage and moist vegetation that Alpacas thrive on, bofedales are localized islands of perennial greenery with deep organic soils moistened by subterranean and considerable surface water often forming small pools. Both natural and artificial bofedales exist, some man-made ones dating back to pre-Inca times. These high-altitude marsh areas can provide year-round forage, allowing herders and their animals to remain in the same area for extended periods. Depending upon water availability, they are productive only during the rainy season or throughout the year. As a result, their carrying capacity is highly variable, from 2-8 Alpacas/ha/year. Natural mojadales compared to irrigated artificial ones, typically have greater plant cover with more palatable and nutritious forage. Vegetative composition of bofedales in the humid Puna varies between several dominant species, including Distichia muscoides, Eleocharis albibracteata, Hypochoeris taraxacoides, Hidrocotilo ranunculoides, Liliaopsis andina, and others. A percentage cover of 64-72% of desirable species (Werneria nubigena, Werneria pymaea, Hipochoeris stenocephala, Ranunculos sp., Carex fragilaris) is excellent Alpaca forage. Reported total accumulated bofedal forage (dry weight) from January to August was 1021 kg /ha that grew at an average rate of 4-2 kg/ha/day. Protein ranged 8-3-13-4% and crude fiber 19-2-34-1%. Annual bofedal growth varies with season: 60% during the summer growing season (January-April), 21% during the transition to the dry season (May-June), and 19% in the dry season (July-December). Wet artificial bofedales have greater sustained productivity than natural bofedales with 10-11% protein in both the wet and dry seasons and capable of supporting 3—4 Alpaca/ha/year. Continuous year-round grazing of native grasslands is the most common grazing management practice used by indigenous herders, but technicians are encouraging enhancement of rangeland conditions through rotational grazing and reducing stocking rates of Alpacas and competing sheep. Recommended stocking rate for Alpacas on Andean native pastures is 2-7 animals/ha/year on excellent range, 2 good, 1 average, 0-33 poor, and 0-17 very poor. However, intensively managed, irrigated pastures of grasses and legumes at 3850 m altitude can support 25 Alpacas/ha/year. Research indicates that despite the high elevations and low night-time temperatures, it is possible to increase considerably the sustained carrying capacity of Andean rangeland by the introduction of improved forage species. Managed pastures of irrigated ryegrass ( Lolium perenne) and white clover (Trifolium repens) with application of nitrogen fertilizers can carry up to 30 adult ind/ha compared with the usual rate of 1-1-5 ind/ha on natural grasslands. On Andean rangelands grazed by Alpaca,tall grass communities are commonly set on fire during the dry season (June—October) by native indigenous herders. The objective is the destruction of bunch grasses that will encourage the growth of ground forage preferred by Alpaca and sheep. However, studies have shown that annual burns are not beneficial because they not only stimulate the rapid regrowth of bunchgrasses, but promote hillside soil erosion and encourage the growth of undesirable invasive plant species. Burning every third or more years during the wet season is a more effective approach for improving Alpaca range and habitat.

Food and Feeding. Historically, an Alpaca was considered to be equivalent to three sheep, but modern animal nutritionists in Peru consider that Alpacas consume 1-2—-1-5 times as much forage as one sheep. Alpacas are selective for these familiar Altiplano plants: Compositae/composites 31 4% (Hipochoires stenocephala, Werneria novigena), followed by Cyperaceae /sedges-rushes 26-1% ( Eleocharis albibracteata, Carexsp.), Gramineae /grasses 19-1% ( Calamagrostis rigescens, Festuca dolichophylla), Rosaceae /roses 14-6% ( Alchemilla pinnata, Alchemilla diplophylla) and minor percentages of Ranunculaceae / buttercups 5:6% ( Ranunculus breviscapus), Leguminosae/legumes 1-7% (Trifolium amabile) and others. Plant leaves,stalks, and flowers with protein content as high as 17-4% are selected by Alpaca when feeding in quality bofedales in the rainy-growing season. Year-round feeding studies on the chemical composition of ingested forage with fistulated Alpacas in Peru and Bolivia yielded the following: dry matter 9-9%, organic material 88-8%, minerals 11-2%, total protein 15-1%, ether extract 7-4%, crude fiber 27-5%, nitrogen-free extract 38-:8%, and detergent neutral fiber 61:6%. General apparent digestibility of bofedal nutrients was dry matter 64-9%, organic material 64-1%, and total protein 64-8%. Total digestible nutrients (TDN) of bofedal forage eaten by Alpacas was similar between the rainy (54-1%) and dry (66:5%) seasons, as was the average energy from TDN at 60-3%. Average daily weight gain per Alpaca grazed on typical (control) bofedales was 0-093 kg, but experimentally at low stocking rates (2 Alpaca/ha/year) weight gain was 0-101 kg/day, medium stocking (4 Alpaca) 0-084 kg/ day, and high stocking (6 Alpaca) 0-079 kg/day. Although the carrying capacity is around one Alpaca/ha/year, overgrazing occurs at 1-8-2-5 Alpaca/ha/year, lowering the quantity and quality of available forage. In indigenous Andean communities where herders own the animals but not the land and the communal grazing lands are used through permission from the community, overgrazing of the natural grasslands is not uncommon. Although efforts are being made to counter the situation, a long history of bofedal overuse by traditional Alpaca herders has frequently resulted in low live (50 kg) and carcass (25-5 kg) weights, reduced fleece weights (1-2 kg), low fertility (35%), and high juvenile mortality (30%). Like Vicunas, Alpacas need frequent water intake. Water consumption by Alpacas grazing on bofedales was high during the dry season at 3-08 kg/animal/day and less in the rainy growing season at 2-04 kg. In another Peruvian study digestibility of high-altitude forage by Alpacas in both Altplano and bofedal habitats was lowest (50-62%) in the winter-dry season and highest (66-76%) in the spring/summer-wet season. Comparative feeding trials measuring the coefficients of digestibility revealed that when fed dry forage low in protein (less than 7-5%) Alpacas were 14% more efficient than sheep, but at high protein levels (greater than 10-5%), sheep were slightly (2%) more efficient. Other studies have reported that Alpacas have a digestion coefficient 25% higher than sheep, particularly on low-quality forage. Maintenance-energy requirements for a 60 kg Alpaca is 2% of its body weight, or 1-2 kg dry forage per day. Alpacas in Peru forage more selectively than Llamas. Diets are highest in grass during the wet and early dry season. As the dry season progresses, the diets of Alpacas in bofedal habitat became largely sedges and reeds (81%). Animals in dryer habitats consume more grass (68%). A study of live weight changes of Alpaca adult males, females, and their progeny, was conducted for three seasons under continuous grazing on natural grasslands on the Mediterranean range of Central Chile. Live weight changes were highest in spring (100-200 g/day), moderate during winter (50-100 g/day), and negative only at the end of summer and in autumn (-110 g/day to — 150 g /day). Weight gains of newborn Alpacas were greatest (110-150 g/day) in the first 90 days after birth and then decreased slightly, reaching values of 75 g /day at 8-5 months old. Weight gainsstabilized at 10-20 g/day at three years of age.

Breeding. Alpaca females in Peru reach puberty at 60% (33-40 kg) of their adult weight, or at c.12-14 months of age when being grazed on native pastures. Although such young females exhibit sexual behavior, ovulation, fertilization, and embryonic survival similar to adults, most breeders waitto first breed females at two years of age when they have reached greater physical maturity. Male Alpacas in Peru are first used for reproduction at two to three years of age, because the penis is still adhered to the prepuce in one-(84%) and two-year-olds (50%), with all males adhesion free at three years old. The rate of detachment is dependent upon the level of testosterone secreted from the testes. The breeding season is from January to April using several different husbandry techniques. If the females are unfamiliar with the breeding male, they most likely will not accept him. Such males become familiarized by staying with the females in the same stone corral or encircled together by rope for a number of hours each day for 20 days; pregnancy rate is as high at 85% using this method. The most common technique is to run four to six breeding males per 100 females together, year-round. Artificial selection is less controlled by this approach, so males with desired traits are chosen (typically white colored, dense and good quality wool, and normally developed testes 4-5 cm long and 2-5 cm wide). On large, Peruvian Alpaca farms no more than 200 females are run with 10-12 males, half of which are rotated in one-week intervals for two months during the breeding season. Males work well for one week, but then begin to fight with each other and establish hierarchies and harems, thus the rotational system. Alpaca breed and give birth seasonally. When males and females are kept together year-round, births only occur during the rainy season from December to March. The continuous association of the sexes produces an inhibiting effect on the sexual activity of the male. But when males are separated from females and only brought together for breeding, births are year-round. Copulation occurs with the female in sternal recumbency, and lasts 20-50 minutes. Non-pregnant Alpaca have no well-defined cyclical sexual activity (estrus), but are always in the follicular phase and state of receptivity until ovulation is induced by copulation. There is no period of sexual inactivity in Alpaca and other cameloids, nor a relationship between size of ovarian follicle and sexual receptivity. Ovulation occurs ¢.26 hours after copulation. Ovulation can be also be induced by the injection of chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), and then occurs c¢.24 hours later. Following ovulation the corpus luteum forms and reaches maximum size and secretory activity at approximately eight days. With no gestation the corpus luteum regresses within 12-18 days after mating, giving way to the formation of new follicles. With conception and gestation, the corpus luteum continues its secretory activity and thereafter the female is not sexually receptive. Pregnancy is assessed by sexual behavior of the female in presence of a new male. Studies have found that at least 85% of the females that ovulate in response to the coital stimulation have at least one fertilized ovum within three days of mating. However, in Peru there is 34% embryonic mortality during the first 30 days of gestation, seriously affecting the annual birth rate of Alpacas. Nearly all (95%) of the pregnancies are in the left horn of the bifurcated uterus, although both ovaries are equally active. Thus, transuterine migration from the right to the left horn of the uterus is common, as evidenced by the corpus luteum in the right ovary and the fetus in the left horn of the uterus. The placenta is simple-diffuse and of the chorial epithelium type. Reproductive studies in Peru on Alpaca mothers (n = 1684) showed that age of the female, year of birth, and the quality of diet were important factors influencing the length of gestation and date of birth. First time mothers at two years of age and those 15 years and older had longer gestation periods (403 and 401 days respectively) than middle-aged females four to twelve years of age (380-390 days). Females grazing on higher quality, cultivated pastures had longer gestation periods than those on native rangelands (389 vs. 379 days). Also in years with favorable vs. poor range conditions, gestation was longer (392 vs. 381 days) and newborns weighed more (8-7 vs. 8-1 kg). The explanation for this may be that females on good forage can afford longer gestations, give birth to a larger young, and be assured that favorable forage will be available for costly lactation. In contrast, females on poor forage have shorter gestations, cannot afford long gestations because of the potential cost of lowering their own health, and need to start lactation as soon as possible while there is at least some forage available before the dry season begins. Age of the Alpaca mother and date of parturition also influenced offspring survival in the Peruvian studies. In a curvilinear fashion, survival of young born to mothers two and three years of age was lower than those with mothers 9-11 years old (82% vs. 91% survival), but declines to 88% for mothers 15 years of age. In Australia, the gestation of spring-mated females is ten days longer than fall-mated females. Birth weight of Alpaca neonates averages 8-4 kg in Peru, with significant variation as indicated among femaleage groups. The importance of good maternal nutrition is critical for such a species with an unusually long gestation. At 180 days or almost half way through gestation the fetus weighs 600 g, only 7% of its eventual 9 kg at birth. Some 93% ofits growth takes place in the last half of gestation, and at 230 days or two-thirds of the way into gestation, a remarkable 72% ofits growth is yet to be gained. The heavy energy demands of lactation lasting 6—8 months, mostly coincides with the Andean rainy, or growing season. Even though multiple ovulations occur c¢.10% of the time, Alpaca twins are extremely rare in Peru and in the USA; only one out of ¢.2000 births. If neonatal twins do occurthere is a significant difference in size, e.g. 4 kg and 6 kg, with the smaller one typically in the right horn of the uterus dying during gestation resulting in the death of the other. After giving birth the female comes into estrus within 48 hours, but only with initial follicular growth. Follicular size and activity capable of ovulation in response to copulation is observed from the fifth day, but the higher rates offertility begin ten days after parturition with the highest fertility 20-30 days postpartum. The Peruvian Alpaca birth season is from December to May. Females are not separated from the herd due to the lack of space. The umbilical of the newborn is treated with iodine or an herb solution to prevent infection and diarrhea. Newborns are watched closely by the herder to assure first nursing is successful (first milk is high in colostrum, rich in antibodies). Parturition in indigenous herds averages a low 50% and juvenile mortality is high (15-35%); itis estimated that no more than half of the female Alpaca of reproductive age produce young every year. Young born during the birth season also had higher survival than those born late. Additionally, juvenile survival is curvilinearly related to birth weight. Neonates weighing 9-11 kg had an average 92% survival but those weighing 4-5 kg survived at a rate of 30-50%. When pregnant females (n = 424) and their young were monitored,it was found that newborn birth weight, and weight and width of the placenta increased with age of the dam reaching a peak at nine years and then declined progressively. Placental efficiency also increased with female Alpaca age, showing a bimodal shape and peaking at 6-11year-old females; more young died from two-year-old females than any other age; and dead neonates weighed less (6-4 kg) than those that survived (7-8 kg). In indigenous herds, young-of-the-year are usually not weaned due to the lack of extra pastures and the labor involved. Instead, young nurse beyond one year of age, including up to the time the mother gives birth again. To impede the yearling from competing with the newborn for nursing, herders will sometimes temporarily pierce the yearling’s nose with a stick. In commercial Alpaca herds weaning occurs in September through October, sometimes until November, when young are 6-8 months old.

Activity patterns. The daily routine or activity pattern of indigenous Alpaca family flocks is quite consistent. After having spent the night in a stone corral or next to the family house (usually a stone hut called a choza), the animals are released or move out on their own to graze for the day soon after sunrise. While the family’s sheep flock is tended by a herder, the Alpaca flock is not accompanied by a herder. Instead,its daily movements and activity patterns while grazing are self-directed within 1-2 km of their home base to local bofedales and other feeding areas of their choice. As sunset approaches, the flock returns to the home site by themselves without being escorted by a herder. Daytime activity budgets (percentage of time) of Alpacas compared to sheep while both species grazed on native-Andean pasture dominated by the favorable forage Festuca dolichophylla, have shown that while other activities were similar, Alpacas fed more (71% vs. 57%) and rested less (11% vs. 25%) than sheep.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Seasonal patterns of Alpaca movement are determined by herders as influenced by the availability of forage, varying from one locality to next. One common annual movement of Alpacas in the Andes is to graze herds during the rainy season (generallyJanuary to April) in lower mountains (3600-4100 m) areas characterized by pampas, slopes, and rounded ridges. Then in the dry season (generally May to December) they are moved up to the high altitudes (4100-5200 m) to find favorable forage, bofedales, and water. When the rainy season begins, they are moved back to lower areas where grasses are beginning to grow and to avoid severe hailstorms and other weather at higher altitudes. Herders, however, without access to two seasonal sites maintain their animals in the same area year-round. Indigenous families that raise livestock in the Peruvian Andes on the average have 70 Alpacas (30-120), 30 Llamas (4-50), and 50 sheep (10-80). More importance is placed upon Alpacas because they offer greater economic diversity. Most (90-95%) of the Alpaca woolis sold, the balance used for home use. Many of the young males one to two years old are sold for meat production, and old animals are culled to make jerky. In three Peruvian Alpaca farms that were cooperatively, family, and individually owned, percent herd composition was females: 60/ 65/ 70; gelded males: 25/30/25; breeding males: 3/4/5; white animals: 70/70/90; and colored animals: 30/30/10. With Alpacas that are owned as private property, each member of the family owns animals but herd control is under the family. Ownership is designated by ear markings or colored yarn. Animals are often given as presents or ceremonial gifts. They play an important role in the rituals, symbols, mythology, and ceremoniesin the life of Andean people. Individual animals are recognized and described by physical characteristics and usually given a name. Alpacas have feminine attributes in the Andean cosmic vision oflife and the world, and generically referred to as “mothers” and “dear mothers.” Alpacas are highly social with strong herding behavior, making them easier to drive when necessary. In small, mixed-sex herds, dominance is clear with a few adult males as the leaders. Alpacas are more skittish and shy with strangers than Llamas. When a free-ranging flock is approached on foot, they will distance themselves more quickly than a herd of Llamas. Once they become familiar with you, however, they are docile and easier to handle than sheep. There are no known unmanaged or feral populations of Alpaca that would allow us to assess their social organization and full repertoire of behavior. However, a number of subtle-contrasting characteristics exist in Alpaca behavior that turn out to be, not surprisingly, very similar to the Vicuna: tighter grouping, vocal communication more common, less communicative with their tails, love water and bathe regularly, greater susceptibility to heat stress, higher site fidelity, males more protective of females, less cooperative, and more distant and stand-offish.

Status and Conservation. Alpacas and Llamas were important to ancient Andean civilizations such as the Tiwanaku Culture that dominated the Lake Titicaca region from ¢.300 BC to 1000 Ap, and the Inca Culture that dominated the Central Andes in the 15% and 16" centuries. When the Incas captured the cameloid-rich kingdoms near Lake Titicaca and south, they acquired giant herds of Llamas and Alpacas. The Incas then sent “seed herds” throughout their empire and commanded that they be reproduced. State-controlled husbandry of Alpacas produced vast herds that numbered into the millions. The Incas placed special emphasis on avoidance of crossbreeding with Llamas and selective breeding of pure-colored Alpacas (brown, black, and white) for quality wool and sacrifice to deities. The Spanish invasion in the 16™ century destroyed that advanced management system and there ensued a breakdown of controlled breeding. Today, the raising of Alpacas in the high altitudes of Peru and Bolivia contributes substantially to the economy of the region. However, animal production is limited by the low level of technology, adverse climate, disease, herders with scarce resources, and frequent over utilization of native rangelands. The Andean grazing system is extensively based upon utilization of native high-altitude grasslands by mixed herds that include not only Alpacas, but sheep and Llamas as well. Pastoralism and mixed agropastoralism form the subsistence base for the agricultural segment of the high Andes. Indigenous communities control the greatest number of camelids and sheep, as well as half of the native rangelands, which comprise ¢.95% ofthe land area above 3800 m. The Alpaca population in South America is c.4-5 million, down some 20% since the mid-1960s, but up 25% from the early 2000s. Today, numbers are at least stable, if not increasing. Most Alpacas are in Peru with 91%, followed by Bolivia 8% and Chile 1%. Few Alpacas occur in Argentina because of the lack of moist Puna and the dominance of the dry Puna. More than 73-87% are in southern Peru (Arequipa, Cuzco, Moquegua, Puno, and Tacna), with nearly half of the world’s Alpaca in the Department of Puno. Females represent c¢.70% of the total Alpaca population. A high percentage (85-95%) of Alpacas are owned and managed by native herders in small flocks ofless than 50 animals, but some commercial Alpaca herds are as large as 30,000 -50,000 individuals. Although indigenous herders raise most Alpacas, productivity traditionally has been the lowest due to over stocking, improper health care, and inbreeding. Peru has ¢.789,775 producers raising Alpacas; Bolivia has 13,603, and Chile 916. Starting in the early 1980s Alpacas were exported from Chile, Bolivia, and Peru to the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Europe, where cottage industries in Alpaca wool have developed. In the USA the Alpaca Owners & Breeders Association numbered over 4500 members with 143,000 registered Alpacas in 2010. Peru exports c. US $ 24 million worth of Alpaca products (wool, tops, yarns, woven fabrics, and knitwear) annually to countries around the world, especially China, Germany, and Italy. Annual Alpaca wool production in South America is 4-1 million kg (90% from Peru), yet only represents 0-6% of the world’s fine-fibered wool production (fine sheep wool is ¢.90-95% followed by cashmere at 5-10%). Because of a high market demand for white wool from Huacaya Alpaca, which can be dyed to any desired color, the Alpaca population has become dominated (80-87%) by white individuals. The result has been a scarcity of individuals with pure natural colors and a reduction of genetic diversity in the species. Pure black Alpacas are the rarest. The problem has been recognized and pure natural colors are now beginning to recover. Alpaca wool prices were at their peak from the 1960s-1980s then declined due to land reforms and competition from synthetics. Prices, however, still remain high at four times the value of sheep wool. In North America in its raw state, an ounce of Alpaca varies from US $ 2 to US $ 5. Each stage of the process (cleaning, carding, spinning, knitting, finishing, etc) adds more value to the wool. As a finished garment, it can sell for US $ 10/0z. In addition to its importance as a producer of fine wool, Alpacas have been a valuable source of meat and hides in South America. In the late 1990s some eleven million kilograms of Alpaca meat were produced annually in Peru, representing 10-15% of the country’s total Alpaca population. The best yield and tenderest meat is from animals 1-5-2 years old, but most are slaughtered at 7-8 years old because their wool has become too coarse for economic production. Alpaca meat is healthful, rich in protein and low in cholesterol and fat. Prime cuts are 50% of the carcass and sold either fresh or frozen to meat markets, restaurants, hotels, and supermarkets. Hides are tanned for soft leather products or sold with the fleece intact as wall hangings, rugs, and toys. For indigenous peoples that raise most Alpacas, family income from these animals is primarily from meat (44% fresh, 16% dried) and secondarily from the wool (31%). Despite its excellent quality, the price received for Alpaca meat is 50% less than that for sheep and beef, due to long standing prejudice towards camelid meat. Beginning in the 1960s Peru was the world leader in quality Alpaca research, especially by the progressive staff and visiting scientists working at the La Raya Research Station from Cuzco University. With the export of Alpacas around the globe starting in the 1990s, serious science on this longneglected species and family expanded to a number of countries. Universities in the USA and Australia pursued vigorous research programs into reproduction, disease, genetics, and nutrition. The future for the Alpaca is encouraging. Wide opportunities exist for improved successful Alpaca production in the highlands of Peru and Bolivia, especially if the stewardship of the Alpaca’s principle habitat, bofedales, is improved towards sustained and balanced use.

Bibliography. Allen (2010), Bravo & Varela (1993), Bravo, Garnica & Puma (2009), Bravo, Pezo & Alarcén (1995), Bryant et al. (1989), Bustinza (1989), Calle Escobar (1984), Cardellino & Mueller (2009), Castellaro et al. (1998), Fernandez-Baca et al. (1972a, 1972b), Flores Ochoa & MacQuarrie (1995), Florez (1991), Gonzales (1990), Groeneveld et al. (2010), Hoffman & Fowler (1995), Huacarpuma (1990), Kadwell et al. (2001), Moscoso & Bautista (2003), Munoz (2008), Novoa & Florez (1991), Orlove (1977), Quispe et al. (2009), San Martin (1989), Sumar (1996), Sumar et al. (1972), Tuckwell (1994), Villarroel (1991).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.