Lama glama (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5719719 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5719727 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03928E69-9A40-FFCE-D0DB-F7C0FB4BF492 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Lama glama |

| status |

|

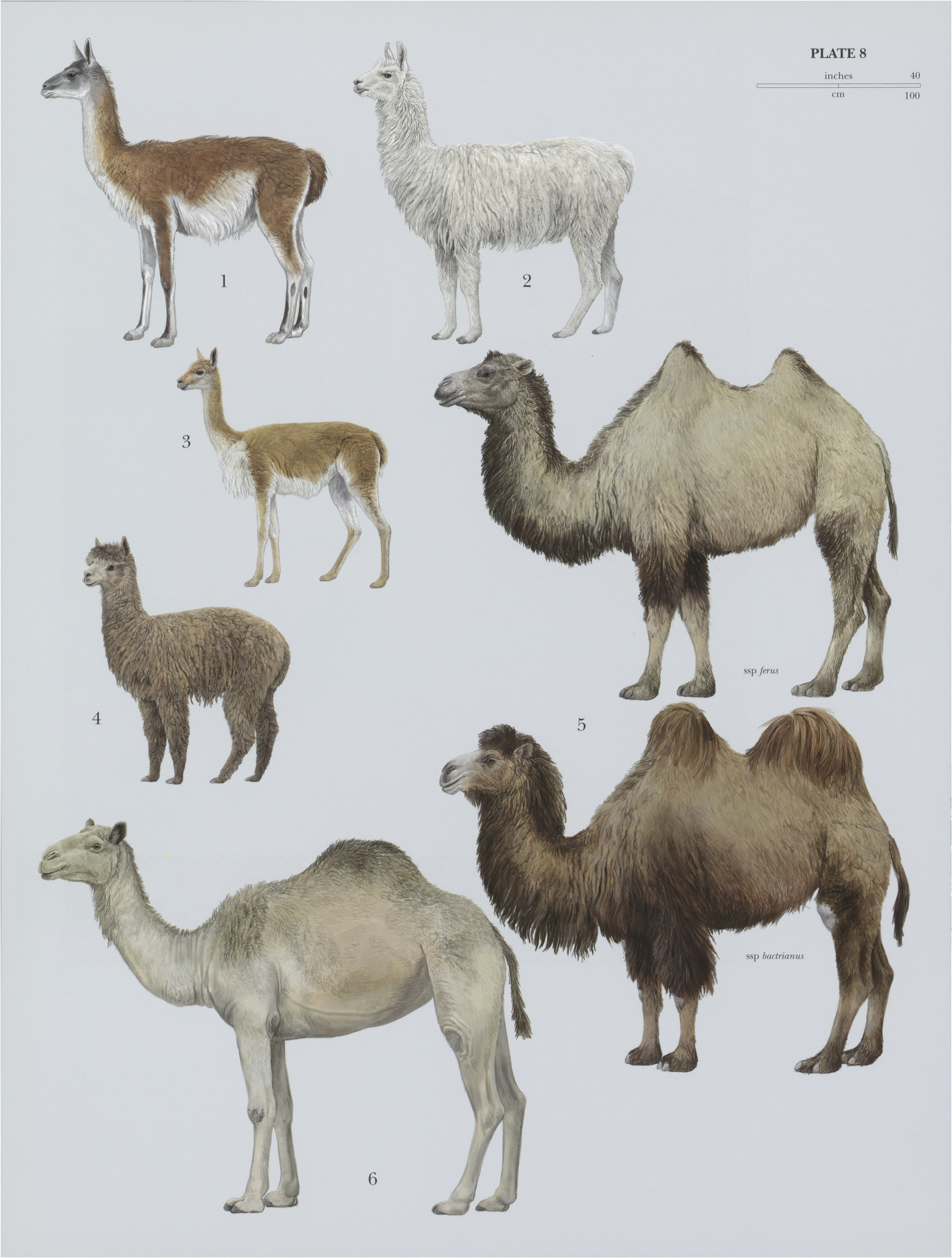

2 View On .

Llama

French: Lama / German: Lama / Spanish: Llama

Taxonomy. Camelus glama Linnaeus, 1758 ,

Peru, Andes.

The Llama was selectively bred from the Guanaco ( L. guanicoe ) for use as a pack animal and producer of meat. It is regarded throughout the world as the premier symbol of South American fauna. With the possibility of more than one center, Llama domestication occurred 4000-4500 years ago in the South-Central Andes (northern Chile and north-western Argentina) and/or 4500-5500 ago in the Central Andes (Junin de los Andes, Argentina). It is often assumed and reported that the Lake Titacaca region was a core of Llama domestication, but supporting data are lacking from early archaeological sites. Osteological remains and DNA analysis document the origin of domestication to be within the range of the northern subspecies of Guanaco L. g. cacsilensis. From its points of domestication, archeological evidence reveals that breeding and herding of Llamas spread widely throughout the Andean region to intermountain valleys, cloud forest on the eastern slope of the Central Andes, southern coast of Peru, to the mountains of Ecuador. Llamas closely resemble their progenitor the Guanaco in almost all aspects of physiology, behavior, general morphology, and adaptability to a wide range of environments. There are no subspecies, but two distinct phenotypic breeds: Short-Woolled and Long-Woolled Llamas.

Distribution. Llamas are found at 3800-5000 m above sea level in the Central Andes, from C Peru to W Bolivia and N Argentina. Llama distribution reached its apex during the expansion of the Inca Empire (1470-1532 ap), when pack trains were used to carry supplies for the royal armies to S Colombia and C Chile. Although originally indigenous and endemic to South America, Llamas have now been exported to countries around the world as a companion animal, featured in livestock shows, used for trekking and backpacking, cottage industry and home use ofits wool, and in North America increasingly utilized as a guard animal for protecting sheep and goats from canid predators. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 180-229 cm, tail 18-22 cm, shoulder height 102-106 cm; weight 110-220 kg. Llamas are the largest of the four cameloids and tallest of all Neotropical animals. Classical, camelid-body shape with long slender necks, long legs, and small head compared to the body. Their pelage can be white, black, or brown with all intermediate shades occurring and a tendency for spots and irregular color patterns. Wild-type Llamas occur with Guanaco coloration. There are two distinct phenotypic breeds. SHORT-WOOLLED LLAMAS: Slim and long-bodied, with short coats and visible guard hairs, Short-Woolled Llamas are typically the breed utilized for carrying cargo and are the more common of the two. In the Altiplano regions of La Paz, Oruro, and Potosi Departments the proportion of Short-Woolled Llamas varies between 65% and 83%, while in the Peruvian highlands they represent 80% of the total Llama population. The fleece is low density, low weight (1-3 + 1-1 kg biennially), and relatively thicker fibers with high medullation of 77-88%. Medullation refers to the presence and degree of medulla at the center of the fiber, and high medullation is “undesirable” because the greater the medullation, the bigger the fiber in diameter and so less fine. LONG-WOOLLED LLAMAS: The less common (17-35%) of the two, this breed is compact, short-bodied, and the pelage has fewer guard hairs. Their wool is longer, covering the entire body, generally uniform, and soft to the touch. The fleece is heavier (2-8 + 1-1 kg), denser, and has finer fibers (26-28 microns) with medullation of 26-33%, and on the average wool coarser than the Alpaca ( Vicugna pacos ). Genetic studies have revealed that 40% of the Llama population shows signs of hybridization with Alpacas. Intentional hybridization has been especially common during the past 25 years both in South America and abroad with the aim of improving wool quality, fleece weight, and economic value. Unfortunately the outcome has been a major loss of pure genetic lines. Indigenous Quechua peoples in the Andes subdivide hybrids into “llamawari” (Llama-like) and “pacowari” (Alpaca-like) based upon physical appearance. Llama ears are banana-shaped (distinctively curved inward) and relatively long (14-16 cm). They are docile, intelligent, and can learn simple tasks after a few repetitions. Mature Llamas weigh an average of 140 kg with full body size reached by four years of age. There are no obvious differences between the sexes, but males tend to be slightly larger. The male prepuce is slightly bent down and directed posteriorly for urination. The female vulva is small, located immediately below the anus, with a nose-like structure pointing out from the base; the compact udderis in inguinal area with four small teats. Llamas are long-lived with a life span of 15-20 or more years. The Llama is woolly in appearance; individual fibers are often coarse, not homogeneous, and have a wide variation in diameter. Its fleece is the heaviest (1.8-3. 5 kg) of the four cameloids, but often of uneven quality. As with the other cameloids, Llama fleece lacks grease,is dry, highly hygroscopic, and naturally lanolin free. Through selective breeding and/or hybridization with Alpacas, some Llama bloodlines have finer-fibered fleeces. The typical Llama fleece is dominated by external guard hair covering (c.56% offleece with fiber diameter 50-70 microns) with an internal undercoat of smaller diameter fibers (c.44% with 25-30 microns). Llama wool is more variable in color and diameter than Alpaca wool. Due to its relative coarseness, [Llama wool has little textile value and is worth half the value of Alpaca wool. Llama woolis rougher to the touch, but with greater felting properties since the cuticle scales protrude more. However, because Llama wool is characteristically strong and warm, it is commonly used by indigenous families for making blankets, ponchos, carpets, rugs, shawls, rope, riding gear, sacks, and “costales"—bags tied to the back of Llamas and used for carrying cargo. Only c.40% of the Llama population is shorn annually because producers want heavy fleeces with long fibers to sell commercially. Some Llamas are not shorn for years because the fleece pads the back for carrying cargo. Annually there are c.1,122,667 kg of Llama wool produced in Peru (60%), Bolivia (34%), and relatively small amounts from Argentina and Chile. In Bolivia an estimated 70% is sold commercially and 30% used for home use. Although the textile industry prefers white, Llama fleeces are of different colors (47% solid, 27% mixed, 25% white). A major problem with Llama woolis its high medullation: without (20%), fragmented (37%), continuous (39%), and kemp/hair (4%). If the fleece wool is separated from different parts of the body and coarse fibers are removed, a favorable proportion of fine wool is obtained. There are no sustainable plans for genetic selection of animals with fine diameter of high value. Although the population of Llamas in Argentina is relatively low, fiber diameter is fine: 48% at 21 microns or less and only 16% at 25 microns and more.

Habitat. In the Andean Altiplano where large numbers of Llamas are raised, the animals are a central part of the agro-pastoral system and the lifestyle of many people, since Llamas are heavily relied upon for carrying cargo and produce. In general these high-altitude grazing lands are low producing with annual production at 200-600 kg/ha for plains and mountainous zones and 600-2450 kg/ha for bofedales. The bofedal habitat is especially important for foraging Llamas during the dry season, yet fragile and susceptible to erosion if overgrazing is permitted.

Food and Feeding. [lamas are considered by their indigenous herders to be extremely hardy because of their ability to prosper in desolate-Andean environments. They have similar feeding habits to Alpacas, but distinct enough to make joint husbandry compatible and possible. Herders view the land andits forage as a single valuable unit because it feeds their Llamas and Alpacas. Land ownership is not important, but traditional use and designated rights to graze particular areas is critical. Studies in the highlands of Peru and Chile on the botanical composition of the diets of Llamas feeding on wet (bofedales) and dry (gramadales) meadows found a high overlap with Alpaca and sheep feeding habits, but significantly differed from Alpacas in the summer (61%) and winter (74%) because the two camelids were managed by herders to minimize competition. Llamas had higher digestion coefficients than sheep of organic matter, crude protein, dry matter, and fiber fractions of bunchgrasses, important forage for Llamas. These feeding trials comparing the abilities of Llamas vs domestic sheep in digesting organic material ofvarious qualities revealed the coefficients of digestibility for low quality to be 51 vs. 41 (24% difference between the species), medium quality 60 vs. 52 (15%), high quality 73 vs. 75 (-=3%), high fiber 58 vs. 52 (12%), medium fiber 62 vs. 58 (7%), and low fiber 67 vs. 65 (3%). Thus Llamas were significantly more efficient than sheep when forage was low to medium quality and high in fiber. Maintenance energy requirements for a 108 kg Llama is 2% of its body weight, or 2-2 kg dry matter of forage per day.

Breeding. The breeding season is from February to May. Males used for breeding are commonly familiar to the females, who when approached sit down in the copulatory position. Unfamiliar males usually have to chase the female and force her to recline. Research and extension agencies encourage herders to use one male with five females for three days, and then remove the male. The male is reintroduced 15 days later and the cycle is repeated until all females are bred. Gestation is 340-360 days. A single offspring is born, although exceptionally twins do occur. The female gives birth standing up, there is no licking of the neonate, and newborns can follow their mother within an hour. Llamas have a high potential for reproduction under good management: 85-95% annual reproductive rate on research and well-managed farms. However, in the Andes due to poor forage conditions frequently available to indigenous herders and the resulting poor condition of animals,fertility has been reported to be as low as 45-55%. In years of severe cold or droughts subadult mortality can be as high as 30-50%. Offspring regularly nurse up to the fifth month and are weaned by the herder at eight months, although if allowed to do so will continue to nurse irregularly until the female gives birth again the following year. Some females breed 8-10 days after parturition, but two to three weeks later is the norm. Mother Llamas are patient with suckling their young and some will accept nursing another female’s offspring. After weaning the young Llamas, some herders separate them from females until two years old, and then segregate them by sex. At three years of age a final selection is made for the best males to be sires with the balance to be used as pack animals or eventually meat. Females are bred at two and half years and not used as beasts of burden.

Activity patterns. Daily activity patterns of Llamas are essentially the same as Alpacas. That is, after having spent the night in or next to a rudimentary stone corral adjacent to the family’s residence (often a single-room hut called “choza” made of stones with a thatched roof), the Llamas move out soon after sunrise to feed in the local highaltitude grasslands, moving and grazing often unattended by a herder, then return to the choza as darkness approaches. Activity budgets (percentage of time) of Llamas compared to sheep grazing on native Andean pasture dominated by favorable forage ( Festuca dolichophylla), have shown that all other activities were similar, but that Llamas feed more (71% vs. 57%) and rested less (15% vs. 25%) than sheep.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. [Llamas (as well as Alpacas) of South America exist within a society of indigenous herders, whose main societal features are seasonal migration, a scattered population without villages or urban centers for permanent residence, and whose social structure is centered around large families with strong ties. Rules and traditions exist within each community that often determines important aspects of herd management. For example, in some systems male [lamas are maintained apart from the female segment in distant community pastures, and then reunited for the breeding/rainy season from January through March. The female segmentis a mixed herd of reproducing and replacement females, young, and one-year-olds of both sexes. When the yearlings are 12-18 months old some herders make a preliminary selection for meat production or future reproduction. Another system used extensively is one in which breeding males are permanently kept with the mixed herds of females year-round. Invariably Llama herders also maintain a flock of sheep that offers an important source of food for the family. A problem, however, is that the sheep compete for forage with the Llamas, reduce the land’s carrying capacity, and increase the probability of overgrazing. Llama herd size averages 40-60 in the more heavily populated communities, compared to 120-180 Llamas in the Altiplano with fewer people. In contrast, average accompanying flocks of sheep average 40-70 animals in both areas.

Status and Conservation. Bolivia has most (58%) of South America’s ¢.3-91 million Llamas, followed by Peru (37%), Argentina (4%), and Chile (1%); nearly all of which (99%) are found in indigenous communities. The total number of Llamas has increased 12% during the past decade. In Bolivia 370,000-500,000 families raise Llamas, in Peru 297,414, Argentina 2803, 80% of which have fewer than 90 animals. There are no known wild or feral populations. Llamas were intertwined with the rise and spread of the Inca Empire since its beginning in the Peruvian Andes in the early 1200s. With the help of Llamas, the Incas built sturdy walls, buildings, irrigation systems, and some 8700 km of roads throughout their empire. These roads eventually extended around 2500 km from Ecuador south to central Chile and parts of Argentina. Before the Spanish Conquest of Peru, Llamas numbered into the multimillions, but were severely decimated during the post-conquest period. While early Spanish chroniclers recorded the “virtual disappearance” of these animals within a hundred years, that was obviously an exaggeration. Indigenous and endemic to the South America, [Llamas have now been exported to countries around the world as a companion animal, featured in livestock shows, used for trekking and backpacking, and increasingly utilized as a guard animal for protecting sheep and goats from canid predators. In the USA there were 162,000 registered Llamas in 2010. Export of Llamas (as well as Alpacas) has increased international interest in these species, stimulating research in the medical, nutritional, reproductive, and disease disciplines. In the Andes, Llamas are viewed and described by native herders by masculine terminology. During ceremonies in which Llamas are being honored or sacrificed, they are referred to as “brothers” and when higher rank or importance is expressed, they are called “fathers.” Indigenous Llama terminology is based upon fleece color, patterns and patches, sex, reproductive status, age, size, shape, wool quality, and behavior. The combinations of these descriptive characters amount to over 20,000 words, forming a rich nomenclature used to identify and distinguish individual Llamas as well as Alpacas. Llamas have long been important beasts of burden for the Andean cultures and nations. Cargo-carrying Llamas have made it possible for peoples of the Andes to successfully inhabit this rugged-mountain environment. Extensive and ritualized prayers are said before departure of a Llama caravan, requesting permission and protection from local deities for the journey, safe passage, and that no incident will befall the Llamas or family members while traveling. Only men of the family travel with the Llama pack train, walking behind the animals. Castrated male Llamas are used primarily, and depending upon their maturity, size, and training, individuals are capable of carrying up to 25-30% of their body weight, or 25-35 kg, and traveling 20-30 km in a day for up to 20 days. The cargo is carried in a sack tied to the Llama’s back with a rope made from coarse Llama wool. Males are castrated at two years of age and training begins by accompanying the older animals on trips. Individual Llamas in the traveling caravan are not tied together, but follow the lead of two to three “Llama guides.” Such lead Llamas traditionally were adorned with colorful halters, frontal tapestries, and even a family or national flag atop its back. Animal leaders are given names to reflect their status, such as Road-Breaker, Condor Face, and Champion. Lead Llamas prevent junior animals from usurping the front position, and guide the way when fording rivers, crossing dangerous bridges, and when negotiating narrow paths along steep ravines. If the lead Llama stops, the entire caravan waits until it resumes traveling. At the end of the day, Llamas are unpacked and turned loose to graze and water. If available, they are kept in stone corrals for the night, otherwise they are grouped together with a rope running around them at neck level. Llama caravans use traditional trading circuits in the Altiplano, some descending into the Andean valleys, the Pacific coast to the west, or the Amazon jungle to the east. Goods are sold, purchased, and traded along the route as needed. From the coastal agricultural valleys fresh produce was obtained in exchange for corn, potatoes, wheat, and barley that were grown and carried down from the mountain agricultural valleys. In times past Llama trains traveled hundreds of kilometers to obtain highly prized salt from inland, natural-salt deposits and mines, some types of which were used for human consumption, others for animals. Today, the world of the Andean Llama herdsmen is rapidly changing with goods and produce now primarily transported by trucks and rail. Still, Llama caravans continue to be used and are especially important for transporting goods to remote regions of the Andes. Secondarily Llamas are used in South America for meat, fuel, and wool. Llama meatis often dried and stored as jerky, typically made by alternative freeze-drying during the Andean winter when nights are freezing and days sunny. With a dressing percentage of 44-48% yielding 25-30 kg of fresh meat, 12-15 kg ofjerky are produced. Jerky is not only a convenient form for long-term storage of meat, but is an excellent source of protein (55-60%). Llama hides are used for making shoes, ropes, and bags. Their fecal matter is valuable as fuel in regions where wood is scarce. It should be noted that despite the presence of many animals, the diet of Andean herdsmen is based upon agricultural produce. They eat little meat and drink no milk. Goat or cow cheese is consumed by some, and when meat is eaten,it is in the form of cameloid jerky or fresh sheep meat. Outside South America the Llama’s cargo-carrying ability has been discovered by hikers, hunters, and forest-work crews in North America, Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Llamas are quiet, gentle, unobtrusive, and easy to manage. Their hardiness, surefootedness, and trainability make them excellent pack animals and trail companions. The Llama’s agility allows them to negotiate terrain that would be difficult or impossible for other pack animals, and because of their padded feet and ability to browse, they have minimal impact on trails and mountain meadows. In North America Llamas have been used highly successfully as guard llamas for protecting sheep and goats from coyote and feral dog predation. Livestock owners report that their annual sheep losses dropped from 11% to 1% after the introduction of a guard llama, and more than half reported 100% reduction in predator losses. Single, gelded males are typically used, although females work equally well. In 2006, they were found across Canada as well as in every USstate. In the USA there were over 11,000 guard llamas in use on some 9500 sheep operations. Remarkably, half the sheep ranchers in Wyoming have guard llamas and they are common on sheep ranches in Colorado (39%), Montana (28%), and Utah (23%). In the Plains States, 23% of sheep producers in North Dakota and 21% in South Dakota use guard llamas. In the Midwest and the Eastern States, Missouri (23%) and North Carolina (24%) lead the way, respectively. Although not a panacea, guard llamas have proven to be a viable non-lethal alternative for reducing predation, requiring no special training and minimal care.

Bibliography. Bravo et al. (2000), Cardellino & Mueller (2009), Flores Ochoa & MacQuarrie (1995), Franklin (1982b), Franklin & Powell (2006), Gonzales (1990), Kadwell et al. (2001), Marin et al. (2007b), Novoa (1984), Quispe et al. (2009), San Martin (1989), Sumar (1996), Van Saun (2006), Wheeler (1984, 2006).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.