Talpa europaea, Linnaeus, 1758

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6678191 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6671976 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/0380B547-B64D-FF9C-9AAB-F9B6FE58CBA1 |

|

treatment provided by |

Valdenar |

|

scientific name |

Talpa europaea |

| status |

|

European Mole

French: Taupe d'Europe / German: Maulwurf / Spanish: Topo europeo

Other common names: Common Mole, Mole

Taxonomy. Talpa europaea Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL ,

“Europe.” Restricted byJ. R. Ellerman and T. C. S Morrison-Scott in 1951 to “Engel- holm, Kristianstad, Sweden.”

Talpa europaea View in CoL is in subgenus Talpa View in CoL and europaea View in CoL species group. Talpa europaea View in CoL from Italy is genetically and cranially highly divergent from the remaining populations and might represent a distinct species. Small blind moles occupying Thrace in Bulgaria and Turkey are usually classified as 1. levantis View in CoL , but they are genetically closer to 1. europaea View in CoL . Because no taxonomic name is available for this lineage, it is here retained in 7. europaea View in CoL . Up to seven subspecies have been recognized in Europe, and this number was frequently reduced to two subspecies that differ in relative rostral breadth: nominate europaea View in CoL and frisius named by P. L. S. Miller in 1776. Morphological diversity in 7. europaea View in CoL is more complex, and four groups have been defined based on variability of cranial shape. In the past, many species of Talpa View in CoL were regarded as synonyms of 1. europaea View in CoL ( altaica View in CoL , caucasica View in CoL , occidentalis View in CoL , ognevi, romana View in CoL , and stankovici View in CoL ). Subspecific taxonomy requires reassessment. Monotypic.

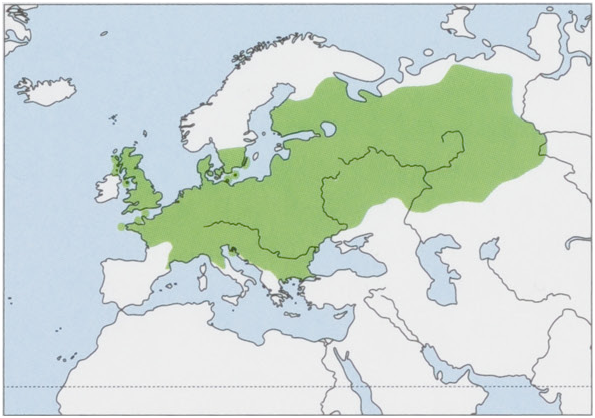

Distribution. Most of Europe, from the British Is and NW France E to W Siberia as far E as Irtysh and Ob rivers, and from S Sweden, S Finland, and S Karelia (Russia) S to N Italy and N Balkans; marginally present also in NW Kazakhstan. In E Europe and in Asia the border roughly follows the extreme extension of the taiga in the N (northernmost record is from Pechora River close to 68°N) and the steppe-forest—steppe transition in the S. Present on some Is in the Baltic Sea and around Denmark (Oland, Funen, Zeeland, Bjgrng, Tasinge, Tung, Langeland, Riigen, Usedom, and Wollin), around Great Britain (Sky, Mull, Anglesey, Wight, and Jersey), offshore W coast of France (Ouessant and Ré), and on Cres (Croatia) as the only Mediterranean I. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 121-159 mm (males) and 113-144 mm (females), tail 26—40 mm (males) and 25-38 mm (females), hindfoot 17-2—20-8 mm (males) and 17-18:5 mm (females); weight 87-128 g (males) and 72-106 g (females). Males average 26-33% heavier than females. Size varies geographically and between years, and European Moles tend to be smaller with increasing latitude and elevation. Furthermore, extremely cold winters select for smaller size. Body is cylindrical, neck is short, and conical head ends in pointed snout. Tail is short and constricted at base; it is usually carried erect. Forelimbs are broad, flat, and oriented sideways. Extra sesamoid bone further enlarges surface area of palm. All five fingers have powerful claws. Hindlimbs are relatively weak, with five toes bearing much smaller claws. Eyes are reduced but still functional, and palpebralfissure is open. There is no external pinna. Fur is dense and velvety, uniformly long, shorter in summer (7-8 mm long), and longer in winter (9-12 mm). Head has shorter hair. European Moles are mainly dark slate-gray to black, slightly lighter underneath. Abnormal coloration is more frequent than in other mammals and includes albino, piebald, cream, yellow, orange, tobacco-brown, and silver variants. Secretions from skin glands provide yellow-brown stain on mid-ventral

hair. Snout is naked, and rhinarium is broad. Extremities are hairless, except for stiff sensory vibrissae that margin forelimbs. Long and stiff hairs sparsely cover tail and have sensory function. Females have four pairs of nipples: two pectoral and two inguinal. Pelvis is of europaeoidal type (i.e. fourth sacral foramen encircled in bone). Skull is long and narrow, tapering gradually from braincase where it is widest. In lateral view, outline is long and wedge-shaped, with rounded off occipital region. Zygomatic arches are weak and parallel. Mandible is slender, ramus is curved downward near middle; coronoid process is large and broadly rounded. Teeth are moderately large. Upper canine is large, with two roots; lower canine is small and resembles anterior incisor; and P is large and caniniform. Remaining premolars have 2-3 roots each. Molars are large, upper molars are triangular, and lower molars consist of distinct trigonid and talonid. Dental formulais13/3,C1/1,P4/4,M 3/3 (x2) = 44. Missing or supplementary premolars are rare. Chromosomal complement has 2n = 34, FN = 68, and FNa = 64.

Habitat. Various habitats with soil deep enough for burrowing and containing suitable prey from sea level up to elevations of ¢.2700 m in mountains of Bulgaria. Abundances of European Moles and earthworms are positively correlated. They consequently avoid acid soils, and critical level is pH 4-5. They originally inhabited deciduous forests but are now widespread in pastures, arable land, parks, and gardens. Sand dunes, marshes, coniferous forests, birch ( Betula , Betulaceae ) woodland, shallow and rocky soils, and alpine pastures are marginal habitats.

Food and Feeding. Earthworms and their cocoons are the main diet of European Moles, and different studies encountered them in more than 50% of stomachs analyzed. Larvae of scarab beetles ( Scarabeidae ), click beetles ( Elateridae ), long-legged flies ( Dolichopodidae ), and crane flies ( Tipulidae ), followed by larvae of lovebugs ( Bibionidae ), dagger flies ( Empididae ), owlet moths ( Noctuidae ), ground beetles ( Carabidae ), various adult insects, centipedes, and mollusks are also eaten. Proportion of different items in a diet does not depend on sex or age. Diet composition is fairly stable throughout the year, but earthworms can be a higher percentage in winter. Earthworms are usually consumed from the head end, with their gut contents ejected; captive European Moles eat smaller species first. Stomach contents weigh an average of 5 g (maximum 12-6 g). A European Mole weighing 100 g needs 60 g of food daily. Captive individuals were maintained on a mixed diet of earthworms, mealworms, maggots, and newborn mice. They voluntarily ate up to 50 g of food at once. Earthworms are cached in expended underground galleries, containing up to 790 earthworms weighing 1500 g (i.e. sufficient amount to feed an individual for more than three weeks). Anterior 3-5 segments of earthworms are removed or mutilated to immobilize them and prevent escape. Caches contain large earthworms (Octolasium and Lumbricus terrestris) in higher proportions than their abundance in the environment, suggesting selective caching. Majority of caches are built up in autumn and are connected with winter nests and fortresses.

Breeding. European Moles are promiscuous. Estrusis short, lasting less than 24 hours. Breeding season starts in February—April, earlier in the south and later in the north. First litter is born in spring, and in some regions, a second litter follows in summer. In western Russia, ¢.9% of females does not reproduce at all, and in the Urals, 15% have two litters. Gestation lasts c.4 weeks. Numbers of embryos are 1-9/female, and the mean varies between 2-5 (Germany) and six (Belarus). About 6-25% embryos are resorbed. Young are born naked and helpless; they weigh 3-2-3-5 g and are 40 mm long. Eyes open at 22 days old when young are 119 m long. During lactation, which lasts 4-5 weeks, females increase food consumption. Young start leaving nests at ¢.33 days old and disperse at 5-6 weeks. They attain sexual maturity in the following year, but in extreme northern Russia, yearling females do not reproduce. Mortality of young (0-5-1-5 years) is 64% in Holland and 85% in Russia. In established populations of European Moles, annual mortality is fairly stable at ¢.50-60%. Overwinter survival correlates negatively with temperature, at least in Russia. European Moles older than three years are rare in a population, and only c.1% attains an age ofsix years. Maximum longevity is ¢.7 years.

Activity patterns. European Moles are fossorial and spend most of their time in extensive and elaborate burrow systems. There can be ¢.6 m of tunnels/m? of meadow. Tunnels are c.5 cm in diameter. Moles dig two kinds of tunnels: surface tunnels that serve as hunting grounds and deep tunnels that are 5 cm to more than 1 m underground. A network of deeper permanent tunnels connects the burrow with hunting grounds. In deciduousforests, European Moles burrow through moss and litter without even entering soil. Light soil or litter is arched up over the top. An individual is capable of excavating up to 30 m of surface tunnels during a single night. Excavated soil is pushed aboveground in molehills, covering an average of 0-14 m*. Molehills are important habitats for larvae of the grizzled skipper (Pyrgus malvae). Beneath each molehill is a sloping or vertical tunnel leading to the underground gallery. To get enough of food, European Moles dig more in poor soil than in good soil. Numbers of molehills therefore reflect habitat quality to a larger extent than densities of European Moles. In a high-density pasture, there can be 4107-21,063 molehills/ha containing 23-63 tons of dirt and covering 4-3-11-2% ofsoil surface. Nevertheless, European Moles only dig for a small proportion of their time and prefer to feed in established burrows. Peak molehill production occurs in spring and autumn. In marshy areas that are prone to flooding and in shallow soils, European Moles occasionally construct large molehills (“fortresses”) containing up to 50 kg ofsoil; they are more permanent and frequently associate with caches. The nest is at ground level but is still insulated by the fortress. Normally, the nest is located below the surface in the central part of the burrow system. Nests are c¢.16 x 20 cm and lined with dry vegetable matter. Each individual has a single nest, but females can construct 2-3 nests during breeding season. European Moles abandon nests with rotten litter. They move aboveground during postnatal dispersion, in search of food, and under abnormal soil conditions, especially extreme droughts. They are able climbers and swim well, willingly to enter water even in winter. If tunnels

are flooded, European Moles move to elevated areas where they immediately start digging. They are active an average of 55% of their time. Diurnal activity is mainly triphasic, with three eight-hour cycles (i.e. 3-4 hours of activity interrupted by equal periods of rest). During each eight-hour cycle, an individual uses a distinct one-third of its territory and tends to return to the same parts on successive days. Activity patterns depend on temporal and spatial dispersion of food rather than interactions between neighbors. Lactating females return to their nest 4-6 times/day; males during breeding season frequently do not reappear in their nest for several days.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. European Moles are solitary and territorial. They scent-mark their territories with secretions from paired anal glands. They show temporal intraspecific avoidance, and two neighbors only exceptionally approach each otherto less than 6 m. Antagonistic interactions are rare. When two individuals engage in an encounter, they fight with forelimbs, bite, and chase each other through tunnels. Fights are rarely fatal. Adults with established territories usually do not disperse. A vacant territory is promptly reoccupied. Home ranges of non-breeding European Moles in England average 2324 m®, regardless of sex. Male breeding territories average 6040 m*. Overlap among home ranges averaged 12-8% of each home range being shared by neighbors. Overlap is less in neighbors of the same sex than in male-female neighbors. Daily home range averages 342 m®. Densities are 0-2-8-5 ind/ha.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The European Mole is included in red books of Voronezh and Omsk regions (Russian Federation). A population on Cres Island is classified as endangered in the Red book of Croatia. In the past, European Moles were trapped for furs in large number in many parts of the distribution. Over one million of skins were traded in 1906 in London alone, and in the 1920s, more than twelve million skins were exported to the USA each year. Between 1934 and 1938 in the former Soviet Union, 23-31 million skins were sent to market annually. This number dropped to 5-6 million annually in the late 1970s and gradually ceased by late 1980s. Trapping was practiced even in marginal habitats in the Republic of Komi (northern Russia) where the peak was reached in 1937 with 21,500 skins harvested. In Poland, ¢.250,000 skins were traded annually before 1960. Moles can disappear from heavily polluted areas; e.g. cooper pollution eradicated European Moles from plots of 90-100 km*. Moles are perceived as pests in farmland because of possible silage pollution from molehills. In parks, sports fields, and ornamental gardens, presence of molehills is frequently considered to be esthetically unacceptable. European Moles are controlled in most countries where they occur, and various types of kill-traps are used. Other methods involve “sonic” mole devices to scare moles, chemical repellents, and poison. In the UK, strychnine could be used to control moles starting in 1963, but it was banned in 2006. A recent postmortem examination of trapped moles showed that acute hemorrhage was the major cause of death from traps, which contradicts the International Humane Trapping Standards and, in at least some countries, national animal welfare standards. An alternative to lethal control of European Moles is reduction of earthworm availability by direct poisoning, lowering soil pH, and by removing litter.

Bibliography. Atkinson et al. (1994), Baker et al. (2015), Bannikova, Zemlemerova, Colangelo et al. (2015), Colangelo et al. (2010), Edwards et al. (1999), Ellerman & Morrison-Scott (1951), Feuda et al. (2015), Funmilayo (1977 1979), Gorman (2008), Gorman & Stone (1990), Hutterer (2007a), Kiris (1973), Kristofik & Danko (2012), Krystufek (1999b), Macdonald et al. (1997), Malkova (2005a), Mellanby (1966), Milner & Ball (1970), Morris (1966), Mller (1776), Nesterkova (2014), Niethammer (1990a), Peshev et al. (2004), Polezhaev (1994), Popov (1960), Prostakov & Harchenko (2011), Skoczen (1958, 1961a, 1961b), Streitberger & Fartmann (2013), Todorovi¢ et al. (1972), Tvrtkovi¢ (2006), Zaitsev et al. (2014).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Talpa europaea

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2018 |

stankovici

| V. Martino & E. Martino 1931 |

caucasica

| Satunin 1908 |

occidentalis

| Cabrera 1907 |

levantis

| Thomas 1906 |

romana

| Thomas 1902 |

altaica

| Nikolsky 1883 |

Talpa europaea

| Linnaeus 1758 |

Talpa europaea

| Linnaeus 1758 |

Talpa

| Linnaeus 1758 |

europaea

| Linnaeus 1758 |

Talpa europaea

| Linnaeus 1758 |

europaea

| Linnaeus 1758 |

europaea

| Linnaeus 1758 |

europaea

| Linnaeus 1758 |

europaea

| Linnaeus 1758 |

Talpa

| Linnaeus 1758 |

europaea

| Linnaeus 1758 |