Dasyurus maculatus (Kerr, 1792)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602779 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FFBB-2457-FFC2-F38908600755 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Dasyurus maculatus |

| status |

|

22. View On

Spotted-tailed Quoll

Dasyurus maculatus View in CoL

French: Quoll a queue tachetée / German: Fleckenbeutelmarder / Spanish: Dasiuro de cola moteada

Other common names: Tiger Cat, Tiger Quoll

Taxonomy. Viverra maculata Kerr, 1792 , Port Jackson, New South Wales, Australia.

In recent genetic (mtDNA and nDNA) phylogenies, the quoll group (D. geoffrou, D. hallucatus View in CoL , D. maculatus View in CoL , and D. viverrinus View in CoL ) form a monophyletic clade; the sister taxon to this group is the Tasmanian Devil ( Sarcophilus harrisiz ). Data from mtDNA more than a decade ago indicated that the two recognized subspecies were not reciprocally monophyletic (although they are very different in size), but the Tasmanian subspecies maculatus View in CoL was reciprocally monophyletic and clearly divergent from mainland animals. Researchers concluded that gracilis and the nominate maculatus View in CoL on the mainland need to be managed separately because they face different threats and are disjunct, and the Tasmanian population should be recognized as a distinct subspecies. Their status is presently is under review. Two subspecies recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

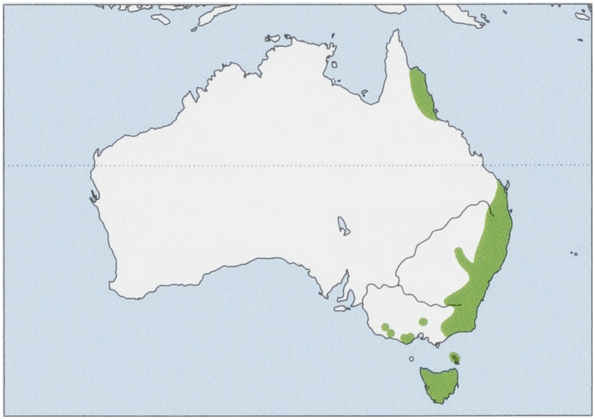

D. m. gracilis Ramsay, 1888 — N Queensland. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 38-759 cm (males) and 35-45 cm (females), tail 37-55 cm (males) and 34-42 cm (females); weight 1.5-5 kg (males) and 0.9-2.5 kg (females) for D. m. maculatus ; head-body 33-51 cm (males) and 31-44 cm (females), tail 31-44 cm (males) and 28:5—41 cm (females); weight 0-85-25 kg (males) and 0.8-1.6 kg (females) for D. m. gracilis . There is marked sexual dimorphism for size. The Spotted-tailed Quoll is distinguished from all other eastern Australian and Tasmanian quolls by its profusely spotted tail and large size (including hindfoot length more than 5:7 cm). There are five fingers on hands and five toes on feet.

Habitat. Treed habitats including tropical, subtropical, and temperate rainforests; wet and dry sclerophyll forests; vine thickets, woodland, and coastal scrub. In Tasmania, the Spotted-tailed Quoll also occurs in heathland. In one field study, Spotted-tailed Quolls were partly arboreal, although most activity occurred on the ground or on fallen logs. Hollow logs were most frequently used as dens; however, rock crevices, burrows, tree hollows, and artificial structures were also used. Fallen timber was used extensively for shelter and traveling and may enhance habitat quality. In another study at three differentsites in south-eastern Australia, habitat use differed among sites, but gullies, drainage lines, escarpments, and ridges were used regularly. Mid-slopes were used less frequently. Habitat use wassignificantly related to prey densities at mostsites. Rock dens appeared to be preferred over log dens, resulting in use of ridges with complex rocky outcrops, which were used as den sites. Complexity of habitats was high in gullies, lower slopes, and riparian flats; moderate on mid-slopes; and low to moderate on upper slopes and ridges. High prey densities and presence of preferred den substrates were the two factors that influenced habitat use by Spotted-tailed Quolls.

Food and Feeding. Generally speaking, diets of Spotted-tailed Quolls include invertebrates, reptiles, birds, mammals, and carrion. Juvenile Spotted-tailed Quolls are more dependent on invertebrates, small mammals, and birds; in contrast, c.70% of the adult’s diet is composed of medium-sized mammals such as small macropods, possums, gliders, rabbits, and bandicoots. One study examined the diet of Spotted-tailed Quolls in north-eastern tablelands of New South Wales by fecal analysis. Mediumsized mammals (0.5-7 kg) formed the bulk of the fecal content in terms of volume and frequency of occurrence. Most frequently consumed vertebrates were Southern Greater Gliders (Petauroides volans), European Rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), Longnosed Bandicoots (Perameles nasuta), Northern Brown Bandicoots (Isoodon macrourus), Red-necked Pademelons (Thylogale thetis), Eastern Ring-tailed Possums (Pseudocheirus peregrinus), Common Brush-tailed Possums (7richosurus vulpecula), and Short-eared Brush-tailed Possums (7. caninus). Insects are frequently eaten, but birds and reptiles occur relatively infrequently in the diet. Seasonal variation in diets of the Spottedtailed Quolls is marked, with insects and reptiles consumed more frequently and mammals less frequently in summer than in winter. Relative volumes of mammals and insects consumed also mirror this seasonal pattern. The Spotted-tailed Quoll is an opportunistic predator, consuming a wide variety of taxa and evidently varying its diet to take advantage of short-term fluctuations in prey abundance. The extremely high proportion of mammals in the diet identifies the Spotted-tailed Quoll as a hypercarnivore—a meat specialist. In other research, the relationship between the diet of the Spotted-tailed Quoll and abundance of its prey was investigated in rain-shadow woodland habitat in southern New South Wales for one year before and two years after a high-intensity, broad-scale wildfire. Medium-sized mammals, particularly brushtailed possums (Trichosurus) and lagomorphs (the European Rabbit and the European Hare, Lepus europaeus—both introduced), followed by small and large-sized mammals dominated the diet before the fire. After the fire, there was a shift in use of food resources in response to changes in prey availability. Brush-tailed possums, lagomorphs, and bandicoots were all significantly less abundant in winter following the fire, and populations of lagomorphs, but not possums, increased in the second winter after the fire. Spotted-tailed Quolls adapted by eating significantly more lagomorphs in each of the two years after the fire and eating proportionately more carrion.

Breeding Female Spotted-tailed Quolls are seasonally polyestrous, and cycle again immediately if they fail to conceive or lose their first litter. They have a 28day estrous cycle and are receptive for 3-5 days during each cycle. Most mating occurs between late May and early August. Females will mate with multiple males and exhibit strong mate choice. Copulation may last up to 17 hours. The pouch, which develops when the breeding season is imminent, contains six teats in two crescent rows. An average litter of five is born in June-August after gestation of c.21 days. Young become free of the teat after c.7 weeks and are left in the den while the female hunts. Males appear to make no investment whatsoever in rearing young. Social play in young is well developed at c.13 weeks, and juveniles are fully independent at 18-20 weeks. Two to four young are typically weaned. Females reach adult size at c.2 years old, and males reach maximum size at c.3 years old. Individuals may live for up to five years in the wild, although in the northern subspecies, most individuals do not survive beyond c.2 years. In one study, Spotted-tailed Quolls were monitored to assess changes in plasma progesterone and fecal estrogens and progestagens, vaginal smears, and qualitative changes in pouch appearance during the estrous cycle. Pouch condition was characterized based on size, color, and secretions and was found to accurately reflect reproductive status, being significantly correlated with changes in sex steroids and vaginal cytology. During the follicular phase, pouch redness and secretions were maximal and were associated with increased sex steroid concentrations and onset of copulation. Post-ovulation, pouches became wet and deep and developed a glandular appearance; plasma progesterone and fecal progestagen concentrations remained high and sustained throughout the luteal phase. These features were identical during the pregnant and non-pregnant estrous cycle.

Activity patterns. The Spotted-tailed Quollis active day and night but more so at night. In one study, 22 trap and 349 radio-tracking locations were used to analyze habitat use of 19 Spotted-tailed Quolls at three sites. Data from radio-tracked individuals at all three sites revealed they used gullies, drainage lines, and escarpments when moving. They followed drainage lines up to saddles and crossed from one catchment to another. They used gullies and escarpments to move and hunt. One male was tracked to a rabbit burrow in the bank of a gully, and other Spotted-tailed Quolls entered rabbit burrows. Movements were recorded both day and night in some locations. At one site, riparian flats and gullies were used for hunting. Individuals were tracked to hollows in trees that were in gullies or on riparian flats. On five occasions, Southern Greater Gliders (Petauroides volans) were observed escaping from trees that Spottedtailed Quolls had been tracked to, and on another seven occasions, they were located in trees. Further, remains of Greater Gliders were found near trees that other Spottedtailed Quolls were tracked to. Hunting for Greater Gliders was only recorded during daylight hours. In another study, researchers tracked 25 Spotted-tailed Quolls (19 males and six females) over an accumulated distance of 10,140 m. Most activity was recorded on the ground (61%) or on top offallen logs (37%). Only 1% of activity was arboreal; maximum height to which an individual climbed a tree was 3 m. A small proportion of activity was also recorded on top of raised rocks or boulders (1%). Spottedtailed Quolls were significantly more active on top offallen logs during the day (43%) than at night (34%), although activity on the ground did not vary significantly. There was no difference between day and night in terms of mean height traveled above the ground or mean vegetation cover that was used.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Spotted-tailed Quolls are solitary and occupy very large home ranges that likely vary in size depending on habitat richness and density of females. Females are territorial but tolerate their own female offspring within their home ranges of 180-1000 ha. Males are not territorial, and their larger home ranges of 2000-5000 ha overlap those of other males and females. Spotted-tailed Quolls may move 3-5 km during their daily activities and have been recorded moving up to 8 km in a single night. In another study, radio tracking of Spotted-tailed Quolls in forested ranges of north-eastern New South Wales also revealed that home ranges were extensive, with males occupying large, overlapping ranges (minimum convex polygon, MCP, up to 757 ha) and females occupying smaller, nonoverlapping territories (MCP up to 175 ha). Spotted-tailed Quolls have a number of vocalizations, including a low hissing sound, a harsh call likened to the “blast from a circular saw,” which is used in conflict encounters, and a soft, clicking “cisp-cisp-cisp” noise, uttered during the mating season. Spotted-tailed Quolls are renowned for their use of latrines (sites with aggregations of feces); these are often on top of boulders or logs, particularly on prominent high points. Peak latrine use occurs during the breeding season, suggesting that latrines enable males to monitor reproductive status of females. Latrines are likely also used to mark territorial boundaries and landscape features and communicate presence without physical contact.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Near Threatened on The IUCN Red List. The Spotted-tailed Quoll occurs in more than 20,000 km?, with an estimated population of.20,000 mature individuals. The subspecies gracilis is listed as endangered in Australia. It is now evidently extirpated from the Atherton and Evelyn tablelands; there are few sightings south of 17° 45’ S. This represents a decline in extent of occurrence of ¢.20% for this subspecies. Mainland nominate maculatus is listed as endangered in Australia, and Tasmanian maculatus is listed as vulnerable. The consensus of experts is that the Spotted-tailed Quoll is seriously threatened; the existing reserve system is fragmented and not large enough to conserve viable populations of a large, mobile mammal with an extensive home range. Landscape-scale management of the Spotted-tailed Quoll is unfortunately complicated by multiple land tenures. In south-eastern Queensland, the Spotted-tailed Quoll has undergone a range contraction suggested to be in excess of 30% over the last 25 years; it is now rare in most areas. Remaining populations exist in southern Darling Downs (Stanthorpe to Wallangarra), Blackall and Conondale ranges, Main Range (Goomburra to Spicers Gap), Lamington Plateau, and McPherson/ Border Ranges (from Springbrook to Mount Lindsay). It is extant in the Australian Capital Territory and eastern New South Wales and patchily distributed as far west as Warrumbungle National Park in New South Wales. The most abundant populations of Spotted-tailed Quolls are believed to be in north-eastern New South Wales, where they are most commonly encountered on the northern coast and ranges from Hunter Valley, Taree, Port Macquarie, to Coffs Harbour, as well as gorges and escarpments of the New England Tableland. In Victoria, the subspecies maculatus is now only patchily distributed through Eastern Highlands, East Gippsland, Otway Range, and the Mount Eccles-Lake Condah area. Records of the Spotted-tailed Quoll from this region since 1970 are concentrated in upper Snowy River Valley, Otway Range, Mount Eccles National Park, Rodger River—Errinundra Plateau area, and around Gippsland Lakes. In Tasmania, the subspecies maculatus is absent from islands and absent or rare in the central midlands and parts of the central eastern coast that have been cleared for agriculture. It is more frequently recorded in wet forests or scrub in north-eastern highlands and in the west of the island. The Spotted-tailed Quoll is presumed extinct in South Australia. Potential threats include loss and fragmentation of habitat through clearing, logging, and inappropriate burning regimes; non-targeted poisoning and trapping; competition with introduced predators; poisoning by eating cane toads (Rhinella marina); and human persecution, especially at poultry yards that they frequent for easy prey. One study investigated non-targeted impact of baiting using sodium monofluoroacetate (compound 1080) to control feral domestic dogs; a population of radio-collared Spotted-tailed Quolls was subject to an experimental aerial baiting exercise. The trial was conducted at a site on New England Tablelands, New South Wales, without a recent history of that practice. Sixteen quolls were trapped and radio-collared before baiting. Fresh meat baits were delivered from a helicopter at a rate of 10-40 baits/km. In addition to 1080 (4-2 mg), each bait contained the bait marker rhodamine B (50 mg), which becomes incorporated into growing hair if an animal survives bait consumption. Two mortalities of Spotted-tailed Quolls were recorded following aerial baiting; however, neither of the carcasses contained traces of 1080. Given that one individual died 34 days after bait delivery, most likely none of the radio-collared quolls succumbed to baiting. Vibrissae samples collected from 19 Spotted-tailed Quolls captured after the baiting showed that 68% had eaten baits and survived. Furthermore, consumption of multiple bait was common, with up to six baits consumed by a single female. Results of the study demonstrated that most, and perhaps all, Spotted-tailed Quolls survived the baiting trial, including those that consumed dog baits.

Bibliography. Belcher (1995), Belcher & Darrant (2004, 2006), Belcher et al. (2008), Burnett & Dickman (2008a), Claridge et al. (2005), Dawson et al. (2007), Firestone et al. (1999), Glen & Dickman (2006a, 2006b), Glen, Cardoso et al. (2009), Hesterman et al. (2008), Jones & Barmuta (1998, 2000), Kértner (2007), Kértner et al. (2004), Maxwell et al. (1996).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Dasyurus maculatus

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

D. hallucatus

| Gould 1842 |

Sarcophilus harrisiz

| F. G. Cuvier 1837 |

D. viverrinus

| Shaw 1800 |

Viverra maculata

| Kerr 1792 |