Pseudantechinus bilarni (Johnson, 1954)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6611402 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FFA0-244E-FA04-FB040CC50A7B |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Pseudantechinus bilarni |

| status |

|

10. View On

Sandstone Pseudantechinus

Pseudantechinus bilarni View in CoL

French: Dasyure de Harney / German: Harney-Fettschwanz-Beutelmaus / Spanish: Falso antequino de Bilarn

Other common names: Harney’'s Antechinus, Northern Dibbler, Sandstone Antechinus, Sandstone Dibbler

Taxonomy. Antechinus bilarni Johnson, 1954 ,

Oenpelli (12° 20° S, 133° 3’ E), Northern Territory, Australia. GoogleMaps

P. bilarni was first collected in 1948 on the American-Australian expedition to Arnhem Land. Its specific moniker was derived from the local Aboriginal pronunciation of the name of an Australian naturalist and author, B. Harney, who was a member of the expedition. There are currently six recognized species of “false antechinuses:” bilarni , macdonnellensis , mimulus , ningbing , roryi , and woolleyae , macdonnellensis , and mimulus were both initially placed under the genus Antechinus , along with Parantechinus apicalis . Nevertheless, with remarkable foresight, G. H. H. Tate in 1947 erected a new genus ( Pseudantechinus ) for the “false antechinuses,” macdonnellensis and mimulus , and a monotypic genus for apicalis (Parantechinus) . In 1964, W. D. L. Ride doubted the validity of Tate’s new genera, and returned all three species to Antechinus . P. bilarni was also initially placed in Antechinus . Later, in 1982, P. A. Woolley examined penile morphology of Ride’s Antechinus supergroup and proposed that macdonnellensis , bilarni , the then undescribed “ ningbing ,” and apicalis formed a distinct group from other Antechinus . M. Archer duly resurrected both of Tate’s genera, consigning macdonnellensis and “ ningbing ” to Pseudantechinus and bilarni and apicalis to Parantechinus . D. J. Kitchener and N. Caputi later described P. woolleyae and recommended that bilarni be switched from Parantechinus to Pseudantechinus , where it dubiously remains. Genetic work on the Pseudantechinus has paralleled morphological research since the early 1980s when P. R. Baverstock and colleagues used allozymes to confirm Tate’s contended genera Pseudantechinus and Parantechinus . Direct sequencing of a variety of mtDNA and nDNA has been conducted over the last decade, with the primary aim of clarifying generic placements within the dasyurid (carnivorous) marsupials. Consensus ofthis work is that the monotypic genera containing Parantechinus apicalis and Dasykaluta rosamondae are evidently discrete from each other and from the genus Pseudantechinus ; P. bilarni is very different genetically from Parantechinus ( P. apicalis ) and all other species of Pseudantechinus . Monotypic.

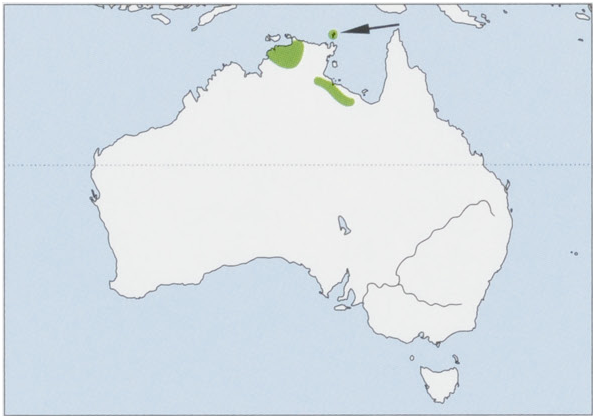

Distribution. Top End of Northern Territory, Australia, from Table Top Range in the NW to Wollogorang Station, and E just over the Queensland border; also occurs on Marchinbar in the Wessel Is. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 9-11.5 cm,tail 9-12.5 cm; weight 20-40 g (males) and 15-35 g (females). Male Sandstone Pseudantechinuses are slightly heavier than females. Fur is grayish-brown above and pale gray below. There is a patch of darker hairs on forehead, and there are chestnut patches behind ears. Tail is long and thin, whereas congeners typically have tails that are fattened at the base.

Habitat. Most common on scree slopes of large boulders covered by open eucalypt forest, with perennial grasses up to 3 m high for much of the year. On the western Arnhem Land Plateau (Little Nourlangie Rock), total numbers of captures of Sandstone Pseudantechinuses per habitat were: 176 males and 145 females in closed forest; 246 males and 294 females on scree slopes; 142 males and 196 females in rocky crevices; and 110 males and 163 females on rocky slopes. Closed forest accounted for 12% of the study area, scree slope 26%, rocky crevices 36%), and rocky slopes 26%. High diversity of plants on the most favored scree slopes provided good ground cover, and the many large boulders over the area evidently provided plentiful nesting sites for Sandstone Antechinuses. This region is subject to monsoonal rains in November-March, with a dry season in May-September when populations of Sandstone Pseudantechinuses may shift to patches of deciduous vine thicket.

Food and Feeding. There is no specific information available for this species, but insects likely comprise a major part of the diet of the Sandstone Pseudantechinus.

Breeding. One study found that breeding in the Sandstone Pseudatechinus occurred once a year, from late June to earlyJuly when scrota of males were largest. After breeding, males showed a temporary decrease in body weight, and size of scrotum decreased until just before the next breeding season. Male Sandstone Pseudantechinuses did not undergo annual die-off characteristic of species of Antechinus and Phascogale . About one-quarter of male and female Sandstone Pseudantechinuses survived to breed in a second season, and some females produced a third litter. Females rarely carried more than 4-5 young in the six-nipple pouch. Up to 15% of young were lost in the first month or two oflife. Females were more active during this period, possibly needing to hunt more to produce sufficient milk for growing young. Maternal mortality was also higher at this time, perhaps because of increased predation on less evasive, heavily burdened females. Young were weaned late in the year and reached sexual maturity by the following June. About three-quarters of young that survived to maturity moved away from the site where they were born. Captive Sandstone Pseudantechinuses have been observed to mate in July and give birth in August, an interval of 38 days. In a capturemark-release study at Little Nourlangie Rock, Northern Territory from February 1977 to June 1979, 174 male and 162 female Sandstone Pseudantechinuses were captured in 34,800 trap nights. Breeding was strictly seasonal, with mating in late June. Pouch young were carried in August-September. Lactation continued until December when free-living young first entered the trappable population. Male Sandstone Pseudantechinuses exhibited seasonal increases in testes’ size, which decreased after mating. Males underwent a second cycle of increase in testes’ size. Histological sampling revealed spermatogenesis during their second breeding season. Males can live well into their third year; males were trapped at ¢.32 months of age. Thus, three age classes of males may be in the population at any one time. In another study, conducted on individuals caught 200-250 km east of Darwin, the period of breeding activity in female Sandstone Pseudantechinuses occurred from at least the latter part ofJuly to mid-August, at which time all females captured were pregnant. Pouch young were subsequently recorded from mid-August to mid-September, and, based on the immature state of young in mid-September,it was estimated they would need to remain attached to teats for at least another 2-3 weeks. Adult females continued to lactate at least into the latter half of November. In a sample of three females bearing pouch young, one carried the maximum number of young (six), one five, and one four. Ofsix females in later stages of lactation in November, average number ofteats suckled was four (range 2-6 teats).

Activity patterns. There is no information available for this species.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. In a mark-release study of Sandstone Pseudantechinuses at Little Nourlangie Rock, Northern Territory, both sexes exhibited two peaks of activity. In males, these activity periods occurred in March— April when young entered the population and in July-August when males were more mobile and seeking mates. There were high numbers of transient males at this time. Female Sandstone Pseudantechinuses exhibited a peak in activity with the influx of young in March-April and another in August-September when mothers are carrying pouch young. This may indicate that females carrying young consume more food and thus spend more time hunting. Nevertheless, because they were not so active during the post-pouch lactation period, it may also be that while they carry pouch young, their hunting efficiency is impaired, necessitating greater activity. Both factors (and others) may explain this behavior. Lower activity of Sandstone Pseudantechinuses in October-November (males) and December—January (females) coincided with generally low captures in traps at those times; not only were fewer individuals caught but those captured were also caught less often.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Near Threatened on The IUCN Red List. There are evidently less than 10,000 mature Sandstone Pseudantechinus remaining in the wild; there have been 20-30% declines of populations at two sites, and the Sandstone Pseudantechinus has been completely lost from anothersite. The overall magnitude of declines of the Sandstone Pseudantechinus is unknown, butit is thought to be less than 10% within ten years, making it close to qualifying as Vulnerable under IUCN’s criterion C. Conservation threats to the Sandstone Pseudantechinus are generally not well known; it is affected by frequent fires, which are major threats. Introduced cane toads (Rhinella marina), poisonous if ingested, might also threaten the Sandstone Pseudantechinus.

Bibliography. Archer (1982c), Baverstock et al. (1982), Begg (1981), Calaby & Taylor (1981), Cooper, N.K. et al. (2000), Kitchener (1991), Kitchener & Caputi (1988), Krajewski & Westerman (2003), Ride (1964), Tate (1947), Westerman et al. (2007), Woinarski (2008a), Woolley (1982, 1995, 2008g).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Pseudantechinus bilarni

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Antechinus bilarni

| Johnson 1954 |