Antechinomys laniger (Gould, 1856)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602859 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FF99-2474-FFCA-FE4806770A87 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Antechinomys laniger |

| status |

|

55. View On

Kultarr

Antechinomys laniger View in CoL

French: Kultarr / German: Springbeutelmaus / Spanish: Kultarr

Other common names: Jerboa-marsupial, Jerboa Pouched-mouse, Jerboa Marsupial Mouse; Pitchi-pitchi, Wuhl-wuhl (spencer)

Taxonomy. Phascogale lanigera Gould, 1856 ,

interior New South Wales, Australia.

This species was once considered to be the marsupial equivalent of the hoppingmouse (family Dipodidae ); indeed, A. lanigerwas long known as the Jerboa-marsupial. J. Gould provided the first description of this species in 1856 (incorrectly depicting it on the branch of a tree when it is in fact ground dwelling). G. Krefft in 1867 transferred it to Antechinomys after the generic description. In 1970, W. Z. Lidicker and B. J. Marlow concluded that based on morphology and ecology, two species, A. laniger (originally named by Gould) and A. spencer: (originally posited by O. Thomas) should continue to be recognized. In 1977, M. Archer included additional specimens, interpreting differences between the two forms as clinal. He believed Antechinomys to be monotypic, containing two allopatric forms, the nominate form and the spencer: form; these are today recognized as subspecies. Even in his early work, Archer considered Antechinomys to have close affinities with dunnarts, Sminthopsis ; thus, in his landmark revision of the genus Sminthopsis in 1981, Archer attributed subgeneric status to Antechinomys . Nevertheless, an early genetic (allozyme) study did not support such a close relationship between these genera and neither did unpublished work on penile morphology, in contrast to several direct DNA studies in more recent times. Today, Sminthopsis is the most speciose genus (currently 19 species) of living dasyurid marsupials and, along with its evidently close relatives Antechinomys (one species) and Ningaw: (three species), constitutes the clade Sminthopsini. Phylogenetic relationships among the 23 species in the Sminthopsini have been the subject of numerous morphological and molecular investigations in recent years. Genetic (several mitochondrial and nuclear genes) phylogenies have failed to support monophyly of the genus Sminthopsis with respect to Antechinomys and Ningawi. In a recent study, there were three deeply divergent clades of Sminthopsis . S. longicaudata wassister to A. laniger ; importantly, this was an alliance also obtained from several previous morphological analyses where there was good reason to include Antechinomys within Sminthopsis and also to link it (based on cranial morphology) with S. longicaudata . The clade containing Antechinomys and S. longicaudata was resolved with strong support in a combined mitochondrial and nuclear data phylogeny to the exclusion of the remaining species of Sminthopsis and all species of Ningauis. Two subspecies recognized.

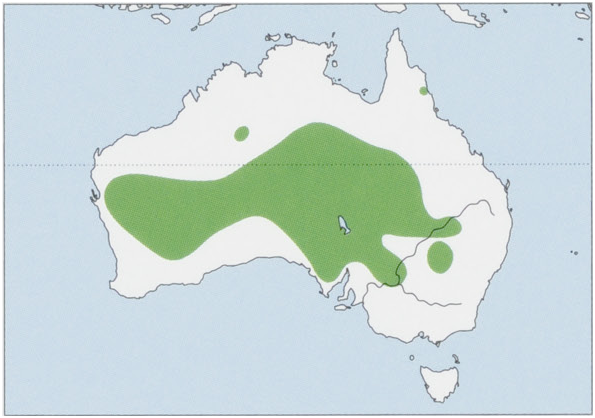

Subspecies and Distribution.

A. l. spenceri Thomas, 1906 — C Western Australia, S Northern Territory, SW Queensland, and N South Australia. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 8-10 cm (males) and 7.9-5 cm (females), tail 10-15 cm (males) and 10-14 cm (females); weight ¢.30 g (males) and ¢.20 g (females). There is sexual dimorphism for size. Kultarrs are grizzled fawn-gray to sandy-brown above and white on chest and belly; midline of face, crown of head, and eye ring are darker. Kultarrs have very large ears and large, protruding eyes. They have long, thin tails with a prominent pencil of dark brown to black hairs. Hindfoot is greatly elongated with only four toes. The nominate laniger may be distinguished from the subspecies spencer byits relatively smaller size, narrower palate, narrower skull, shorter caudal brush, shorter ears, shallower skull (with smaller tympanic wings), and typically possession of eight (opposed to six) nipples in pouch.

Habitat. Desert plains and stony and sandy lands where grasses and small bushes are the predominant vegetation;it is also found in Acacia (Fabaceae) scrubland. The eastern Australian subspecies laniger shows a preference for sparsely vegetated clay pans among Acacia woodland, whereas the central and Western Australian form spencer: seems to prefer stony granite plains dominated by Acacia , Eremophila (Scrophulariaceae) , and Cassia (Fabaceae) scrubland. Kultarrs have been found sheltering in logs or stumps, beneath saltbush and spinifex (7riodia spp., Poaceae ) tussocks, and in deep cracks in soil at bases of Acacia and Eremophila trees. The Kultarr also is found in burrows of other animals such as trapdoor spiders, hopping-mice, goannas, and agamid lizards, but it is unknown if wild Kultarrs will dig their own burrows. Captive individuals will dig shallow burrows and cover entrances with grass. Kultarrs have been found on land severely degraded by domestic cattle in central and western Australia, but this may reflect previous high productivities of such landscapes rather than any benign effect of cattle on the Kultarr.

Food and Feeding. Great lengths of hindlegs of Kultarrs supported the early view that they hopped, but studies have consistently shown quadrupedal locomotion, bounding rapidly from hindlegs to forelegs. This gait gives the Kultarr great maneuverability, permitting it to rapidly change direction by pivoting on its forefeet, which it does to evade predators or avoid being bitten by dangerous prey such as spiders or centipedes. Kultarrs feed predominantly on insects such as spiders,crickets, and cockroaches. One study found that rate of passage of food through the digestive tract, using mealworm cuticle as a marker in minced beef, was 1-6 hours and mean retention time was 3-9 hours. This rapid transit time was consistent for an animal of equivalent body mass, dietary preference, and gastrointestinal tract.

Breeding. The Kultarr has a long breeding season; both sexes are potentially capable of breeding in more than one season. Timing of breeding is different in geographically separated populations, and this evidently depends on photoperiod. Captive unmated females from south-western Queensland entered successive estrous cycles in July-February. Estrous cycles in August—January are typical of unmated Western Australian females. Studies in captivity indicate that individuals are capable of producing offspring in their second and third year of life. Gestation in captivity is more than twelve days, but exact length has not been determined. Field study indicates that females become pregnant during the first estrous cycle of the season, and most have a full complement of pouch young. Females have either six (subspecies spenceri) or eight (subspecies laniger ) teats. Young have been reported in the pouch in August-November. Pouch is a crescent-like fold of skin covering anterior part of mammary area; it develops during the breeding season and later regresses. Pouch protects young during initial stages of suckling. After c.30 days when young are ¢.25 mm long, they may be left in a nest. Later, they ride on their mother’s back during forays. Weaning takes place at ¢.3 months of age. Vocalizations between mother and young are used for mutual location; these are important in prompting retrieval of young straying from the nest or those dislodged from their mother’s back while on the move.

Activity patterns. Kultarrs are nocturnal and likely spend much of the night foraging. They are known to enter torpor. One study found that torpor lasted 2-16 hours. Longest durations were observed at 13-20°C; below and above this temperature range torpor bouts were shorter.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Kultarrs are ground dwelling and predominantly adapted to life in open country, but virtually nothing is known about movements and home range. Kultarrs appear to undergo fluctuations in population size, and they are considered rare and scattered. Kultarrs are notoriously difficult to trap using standard trapping techniques.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Kultarr is apparently not directly affected by human activity, but like other dasyurids,its security may be reduced by changed or intensified land use. Overall, the Kultarr does not appear to be threatened or vulnerable, but some populations, in areas such as southern New South Wales (where no specimens have been recorded since 1900), may be extinct. The Kultarr also appears to have disappeared from some parts of western New South Wales (Riverina and the north-west) and Queensland (Sandringham). Kultarrs occur in the southern Wheatbelt of Western Australia, western Goldfields, Ashburton, and Carnarvon Basin, Western Australia, where its apparent scarcity may be a trapping artifact. There are recent records of Kultarrs from north-eastern South Australia, Yellabinna Regional Reserve, western South Australia, and south of Lake Frome. At a site on Macumba Station in the stony desert area of northern South Australia, Kultarrs were trapped on every visit between July 1992 and mid-1996; drier conditions and increasing cattle degradation did not seem to lead to a noticeable drop in numbers. Species-specific trapping techniques need to be developed to permit effective survey and monitoring of Kultarrs. Other conservation steps need to be used, including long-term monitoring to validate adequacy of conservation activities, collation of distributional data, identification and status determination of the Kultarr across its distribution, construction of a habitat model to more accurately determine extent of source and sink habitat available to the Kultarr, and identification of used habitat patches to permit monitoring of changes in habitat quality, particularly due to excessive flooding and grazing. Home range, movement, habitat, and food requirements need to be studied over the long term, if a suitable study population can be located.

Bibliography. Archer (1977 1981a), Baverstock, Adams & Archer (1984), Baverstock, Archer et al. (1982), Geiser (1986), Geiser & Kortner (2010), Gould (1856), Haby, Foulkes & Brook (2013), Happold (1972), Krajewski et al. (2012), Krefft (1867), Lidicker & Marlow (1970), Maxwell et al. (1996), Morris, Woinarski, Ellis et al. (2008), Stannard & Old (2010, 2011), Valente (1984, 2008), Van Dyck et al. (1994), Woolley (1984a).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Antechinomys laniger

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Phascogale lanigera

| Gould 1856 |