Sminthopsis virginiae (de Tarragon, 1847)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602917 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FF97-247B-FFD5-F3340A440459 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Sminthopsis virginiae |

| status |

|

Red-cheeked Dunnart

Sminthopsis virginiae View in CoL

French: Dunnart a joues rouges / German: Queensland-SchmalfuRbeutelmaus / Spanish: Raton marsupial de mejillas rojas

Taxonomy. Phascogale virginiae de Tarragon, 1847 ,

type locality not given. Restricted by M. Archer in 1981 to “ Herbert Vale , Queensland, Australia.”

The Sminthopsinae have been subject of considerable morphological and molecular investigation, but confusion remains among some taxonomic relationships. A recent representative genetic phylogeny failed to support monophyly of the genus Sminthopsis with respect to Antechinomys and Ningaui . There were three deeply divergent clades of Sminthopsis . In one clade, S. longicaudata was sister to A. laniger . Another clade was composed of the traditional morphologically based Macroura Group: five Sminthopsis comprised a strongly supported clade that included S. crassicaudata , S. bindi , S. macroura , S. douglasi , and S. virginiae . S. virginiae was described by L. de Tarragon in 1847. In 1887, R. Collett noted that the type specimen was lost (along with its locality), and he dutifully described another specimen collected by C. S. Lumholtz that matched Tarragon’s description, from Herbert Vale (north-eastern Queensland). In 1897, Collett named nitela based on a few specimens collected by K. Dahl from Daly River, Northern Territory, which had been proffered by local Aborigines. Later (1922), O. Thomas gave the name rufigenis to a specimen from the Aru Islands. In 1934, T. Iredale & E. Le G. Troughton upset the applecart by referring Collett’s replaced north-eastern Queensland type specimen to S. lumholtzi in honor of the collector. G. H. H. Tate’s later work (1947) suggesting a synonymy of lumholtzi under rufigenis largely fixed the problem; the name lumholtzi has all but been lost in the taxonomic wake. We have a remnant of three subspecies today: virginiae , nitela, and rufigenis. Interestingly, genetics from more than a decade ago showed that mtDNA sequence divergences between the form nitela (Northern Territory) and the two other S. virginiae (Queensland and New Guinea) subspecies are equivalent to, or greater than, those noted between other dunnart species. Allozyme divergences between these subspecies were admittedly slightly lower; thus determination of whether nitela should be returned to full species status (as S. nitela, as Collett intended) requires further study. The latter subspecies may itself be a composite of several distinct forms within its distribution. Morphological evidence supports this division. Sminthopsis virginiae nitela lacks a continuous anterior cingulum on upper molar teeth, whereas one is present in the nominate form virginiae and rufigenis, as noted by M. Archer. Attempts to interbreed one male nitela and one female rufigenis were unsuccessful. In contrast, there is apparently no barrier to breeding between virginiae and nitela. Dasyurids of the same species will often not breed in captivity so these data are inconclusive on the question of reproductive isolation between the forms. Nevertheless, the three subspecies of S. virginiae appear to use different reproductive strategies: nominate virginiae and rufigenis are capable of breeding year-round and nitela is probably a seasonal breeder. All told, there is good evidence that the present taxonomy needs work. The three subspecies are retained here with a cautionary note that revision is needed; one or more may need to be returned to full species. Three subspecies recognized.

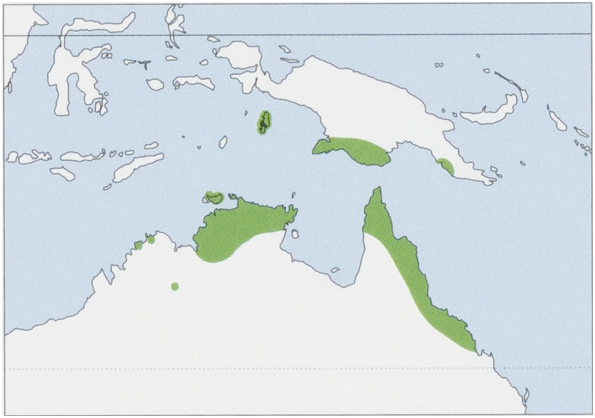

Subspecies and Distribution.

S.v.virginiaedeTarragon,1847—NEAustralia,inNEQueensland.

S. v. rufigenis Thomas, 1922 — S New Guinea (Trans-Fly regions and Central Province of P.a. New Guinea) and the Aru Is. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 9:6-13.5 cm (males) and 9-13.3 cm (females), tail 10-13.5 cm (males) and 9-12.2 cm (females); weight 31-58 g (males) and 18-34 g (females). The Red-cheeked Dunnart has pale-tipped, coarse, dark gray fur above and white to buff fur below. Pale fur tips give it an overall speckled appearance. It has a striking black face-stripe and rufous cheeks. The Red-cheeked Dunnart is a distinctive species of Sminthopsis . Tail is usually sparsely covered with short, dark hairs, but interestingly, some individuals from Northern Territory have pale tails. Growth of Red-cheeked Dunnarts appears to continue throughout life, albeit more slowly after sexual maturity; differences in age may explain the wide range in size recorded for wild-caught adults. Measurements provided above are for the largest series obtained from Western Province in Papua New Guinea, but Australian specimens typically fall within these ranges.

Habitat. Grassland savanna in New Guinea and woodland savanna and grassland, swampy and wetland habitats, and agricultural landscapes such as sugar cane plantations in Australia. All forms of Red-cheeked Dunnarts inhabit types of savanna woodlands and probably nest on the ground under the cover of dense vegetative material, such as Pandanus (Pandanaceae) fronds or thick grass. One study on the Mitchell Plateau in northern Western Australia found that Red-cheeked Dunnarts occurred on deepersoils of riparian and escarpment sites and occasionally on laterites of the plateau itself.

Food and Feeding. The diet of the Red-cheeked Dunnart consists largely of insects, but they are capable ofkilling and eating small lizards and probably other small mammals.

Breeding. Red-cheeked Dunnarts from the Western Province and Queensland have been bred in captivity. Length of estrous cycle is ¢.30 days; interval between mating and birth of young is c¢.15 days. Number of young that can be reared by females is limited by number ofteats (eight in subspecies nitela and virginiae and six in rufigenis). Young suckle for 65-70 days and are considered mature at 4-6 months old. In captivity, the Red-cheeked Dunnart will breed throughout the year; whether it will do so in the wild is unknown. There appears to be no barrier to breeding between Australian forms (e.g. a Queensland male virginiae sired young by a Northern Territory female nitela), but a barrier may exist between the New Guinean (rufigenis) and Australian ( virginiae and nitela) forms. Three attempts, over successive estrous cycles, to mate a Northern Territory (nitela) male with a New Guinean (rufigenis) female were unsuccessful.

Activity patterns. There is no information available for this species.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. There is no information available for this species.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Redcheeked Dunnart has a wide distribution, presumably has a large overall population, and does not face any major conservation threats. In Australia,it is thought to suffer from predation by domestic and feral cats. The Red-cheeked Dunnart occurs in a single protected area on the island of New Guinea butis present in numerous reserves in Australia. Unfortunately, virtually nothing is known about the ecology of the Redcheeked Dunnart, although populations may be affected byfires (that frequent much of their distribution) and rainfall. For example, increased abundance of Red-cheeked Dunnarts was observed in Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, after a series of unusually good wet seasons. One interesting study investigated if Red-cheeked Dunnarts attack cane toads (Rhinella marina), and if so, if individuals subsequently learn to avoid toads as prey. All toad-naive Red-cheeked Dunnarts attacked toads during their first encounter. Most individuals bit the toad on its snout, killed it by biting the cranium, and promptly consumed the toad snout-first, therebyinitially avoiding the toad’s deadly parotid glands. Notably, most Red-cheeked Dunnarts only partially consumed toads before discarding them, and only one individual showed visible signs of toad poisoning. Researchers concluded that all studied Red-cheeked Dunnarts rapidly learned to avoid toads as prey afterjust 1-2 encounters. Red-cheeked Dunnarts rejected toads as prey for the remainder of the study (22 days), suggesting a long-term retention of knowledge that toads are noxious.

Bibliography. Archer (1981a), Baverstock et al. (1984), Blacket, Adams et al. (2001), Blacket, Cooper et al. (2006), Bradley et al. (1987), Braithwaite & Lonsdale (1987), Collett (1897), Flannery (1995a), Helgen, Dickman, Lunde et al. (2008), Iredale & Troughton (1934), Krajewski et al. (2012), Luckett & Woolley (1996), Taplin (1980), de Tarragon (1847), Tate (1947), Thomas (1922), Waithman (1979), Webb et al. (2011), Woolley (2008m).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Sminthopsis virginiae

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Phascogale virginiae

| de Tarragon 1847 |