Ningaui yvonneae, Kitchener, Stoddart & Henry, 1983

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6608102 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6602857 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/EA7087C1-FF86-246B-FF09-F9D908100CF1 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Ningaui yvonneae |

| status |

|

54. View On

Southern Ningaui

French: Ningaui austral / German: Yvonnes Ningaui / Spanish: Ningaui meridional

Other common names: Kitchener's Ningaui, Mallee Ningaui

Taxonomy. Ningaui yvonneae Kitchener, Stoddart & Henry, 1983 ,

“Mt. Manning Area, Western Australia Goldfields, 29° 58’ S.. 119° 32" E.”

M. Archer described the genus Ningaui in 1975 with two species: N. timealeyi (from the Pilbara region in Western Australia) and N. nde: (from central Western Australia). Nevertheless, N. yvonneae was not recognized until later, based on skull morphology. In 1983, phenetic and phylogenetic analyses of skull morphology of 14 geographical groups of Ningaui indicated three species and that accurate identification of individuals to species was possible using skull characters but not external morphology. The genus Ningaui has the greatest similarity morphologically and genetically with the dunnarts (genus Sminthopsis ). In the same year that N. yvonneae was raised, allozyme electrophoresis of 28 loci to characterized 30 specimens of Ningawi from four Australian states. The ningauis fell into three genetic groups, with large differences between groups (21-32% fixed differences) and homogeneity within groups. One group from the Pilbara of Western Australia was shown to represent N. timealeyi ; a second group extending from the Kalgoorlie area of Western Australia to the far west of South Australia and north to the Tanami Desert of the Northern Territory was N. rides; and a third group extending from the Kalgoorlie area of Western Australia (where it is sympatric with N. ridei ) across southern South Australia and into north-western Victoria was identified as N. yvonneae, a species that had only been formally described that very year on the basis of skull morphology. Recent genetic (mtDNA and nDNA) studies have consistently resolved monophyly for Ningaui , but the genus Sminthopsis was not resolved as monophyletic with respect to Ningaui (or, interestingly, Antechinomys ). Within Ningaui , N. timealeyi was consistently resolved as a well-supported sister of a clade containing N. ridei and N. yvonneae. These genetic relationships accord with morphology because N. timealeyi can be distinguished from congeners by size and shape of footpads, nipple number in females, and some skull features, whereas N. ridei and N. yvonneae are unfortunately indistinguishable based on external features. Monotypic.

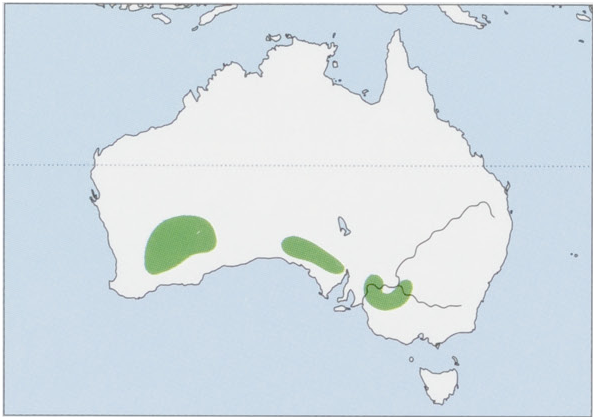

Distribution. S Australia, including S Western Australia, S South Australia, SW New South Wales, and NW Victoria. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 4-8-8:-1 cm (mean: 7-2 cm for males and 6-4 cm for females), tail 5.3-7.1 cm (mean: 6-2 cm for males and 6 cm for females); weight 6-14 g (mean: 10 g for males and 9 g for females). There is subtle sexual dimorphism for size. The Southern Ningaui can be distinguished from the Pilbara Ningaui ( N. timealeyi ) by its hindfoot, which has pads on rear of sole that are smaller and less obvious. The Southern Ningaui and the Wongai Ningaui ( NN. ridei ) are apparently sisters, based on genetic phylogenies. They are very similar morphologically; only skull characters can separate them. The Southern Ningaui has relatively smaller auditory bullae (ear bones) than the Wongai Ningaui.

Habitat. Spinifex ( Triodia spp. , Poaceae ) grassland and also heathland and low shrub and lowland (mallee) scrub habitats. The Southern Ningauiis a little-known species, with only one population on Eyre Peninsula in South Australia studied in detail. Dense spiny nature of spinifex provides permanent cover and invertebrate prey. Indeed, although the Southern Ningaui has been caught in areas where spinifex is sparse, finescale assessment of habitat use suggests it is a key habitat component; activities of individuals appears to be centered in and around spinifex hummocks.

Food and Feeding. Southern Ningauis feed on a wide variety of prey, the majority of which is smaller invertebrates caught among leaf litter. They subdue their prey quickly, usually giving a killing bite to the head before quickly devouring it headfirst. The Southern Ningaui can consume a large proportion of its body weight in a single night's foraging. One study of twelve individuals taken in pitfall traps from South Australia and maintained in captivity indicated that they fed opportunistically on invertebrates, dominated by Hymenoptera , Coleoptera , and Araneae . Nevertheless, the Southern Ningaui also consumed vertebrates, such as skinks. When presented with a choice of prey, Southern Ningauis consistently selected small prey items over large. Presumably, small prey items represent the most energy-efficient prey option, because the Southern Ningaui can more efficiently capture, subdue, and consume them than larger prey. Another study examined diet in Southern Ningauis inhabiting semi-arid mallee country in South Australia. Southern Ningauis included a variety of prey types in their diet, with eleven invertebrate taxa recorded from direct observation, eight of which were detected in feces. Taxa consumed most often by freely foraging Southern Ningauis were Araneae, Blattodea , and Orthoptera ; those most commonly detected in feces were Hymenoptera and Araneae . Taxa most commonly recorded in pitfall traps were Hymenoptera, Collembola , Coleoptera , and Acariformes. Male Southern Ningauis generally consumed more diverse prey than females, and they were more likely to consume Hymenoptera and Isoptera. Females were more likely to consume Lepidoptera and Hemiptera. Southern Ningauis captured prey from all available habitat components, but leaf litter and spinifex were the most commonly recorded capture sites. Southern Ningauis, like many other dasyurids, have a largely generalist insectivorous diet, but they do show some selectivity of certain taxa, particularly Blattodea, Orthoptera, Chilopoda, Lepidoptera, and Araneae .

Breeding. Studies from a population in the Middleback Ranges in South Australia indicate that breeding is primarily in midto late spring, with females rearing 5-7 young/ litter. Juveniles enter the trappable population in February, at which time they compose c.97% of the population. Thus, adults have an average life span of c.14 months and mostly disappear from the population after December; populations are composed of a single cohort for much ofthe year. There is no male die-off, and females are probably polyestrous, so there is at least the potential for a second litter in a season. One study of museum specimens indicated that male Southern Ningauis reached sexual maturity in their first year, so after the end ofJuly almost all male Southern Ningauis were considered reproductively mature.

Activity patterns. In one study of captive Southern Ningauis, they entered torpor frequently when food wasavailable; withdrawal of food increased occurrence of torpor to almost 100%. Minimum body temperatures during torpor of Southern Ningauis were lower, and torpor duration longer, than for many larger dasyurids. Apparently thermal stress on very small species such as the Southern Ningaui exerts a strong selective pressure to enhance daily torpor episodes to reduce heat loss.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. One study of a population of Southern Ningauis in South Australia indicated that although it was known to make occasional long-distance movements (up to 2 km), most distances between consecutive captures were much shorter (averaging less than 100 m). Females are apparently fairly sedentary; males exhibit much greater mobility, regularly moving more than 200 m between recaptures. This is particularly so during the breeding season when average distance moved can increase by up to 400%. Male Southern Ningauis tend to make much greater movements during the breeding season. Lower mobility during pre-breeding may coincide with temporary establishment of home ranges by males and less need to move around the landscape. In fact, this may be an important survival strategy during winter, permitting Southern Ningauis to become familiar with good foraging areas and refuge burrows in times of stress. Few adult Southern Ningauis remain alive beyond the end of breeding season; the few that do so (aged more than 14 months) may increase survival chances by establishing more permanent home ranges during a time of intense competition (because there is an influx ofjuveniles).

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Southern Ningaui has a wide distribution and presumably a large overall population, and it does not face any major conservation threats. Inappropriate fire regimes, grazing of domestic sheep, and mineral sand mining are localized threats and may lead to habitat fragmentation. The South Ningauiis present in many protected areas, several of which are located in Western Australia. Further studies are needed into distribution, abundance, and natural history of the Southern Ningaui. It is susceptible to fire. One study aimed to determine effects of an extensive wildfire (118,000 ha) on a small mammal community in mallee shrublands of semi-arid Australia. Small mammal surveys were undertaken concurrently at 26 sites: once before the fire and four times following the fire (including 14 sites that did not burn). Wildfire had a strong influence on vegetation structure and occurrence of small mammals. The Southern Ningaui showed a marked decline in the immediate postfire environment, corresponding with a reduction in hummock-grass cover in recently burnt vegetation.

Bibliography. Archer (1975), Baverstock et al. (1983), Bos & Carthew (2001, 2003, 2007a, 2007b), Carthew & Bos (2008), Carthew & Keynes (2000), Ellis, Menkhorst, van Weenen & Burbidge (2008a), Geiser & Baudinette (1988), Kelly et al. (2010), Kitchener, Cooper & Bradley (1986), Kitchener, Stoddart & Henry (1983), Krajewski et al. (2012), Woolnough & Carthew (1996).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

SubClass |

Metatheria |

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Ningaui yvonneae

| Russell A. Mittermeier & Don E. Wilson 2015 |

Ningaui yvonneae

| Kitchener, Stoddart & Henry 1983 |