Macaca fascicularis (Raffles, 1821)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863175 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFD0-FFD6-FAE9-629DF8B9F5F8 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Macaca fascicularis |

| status |

|

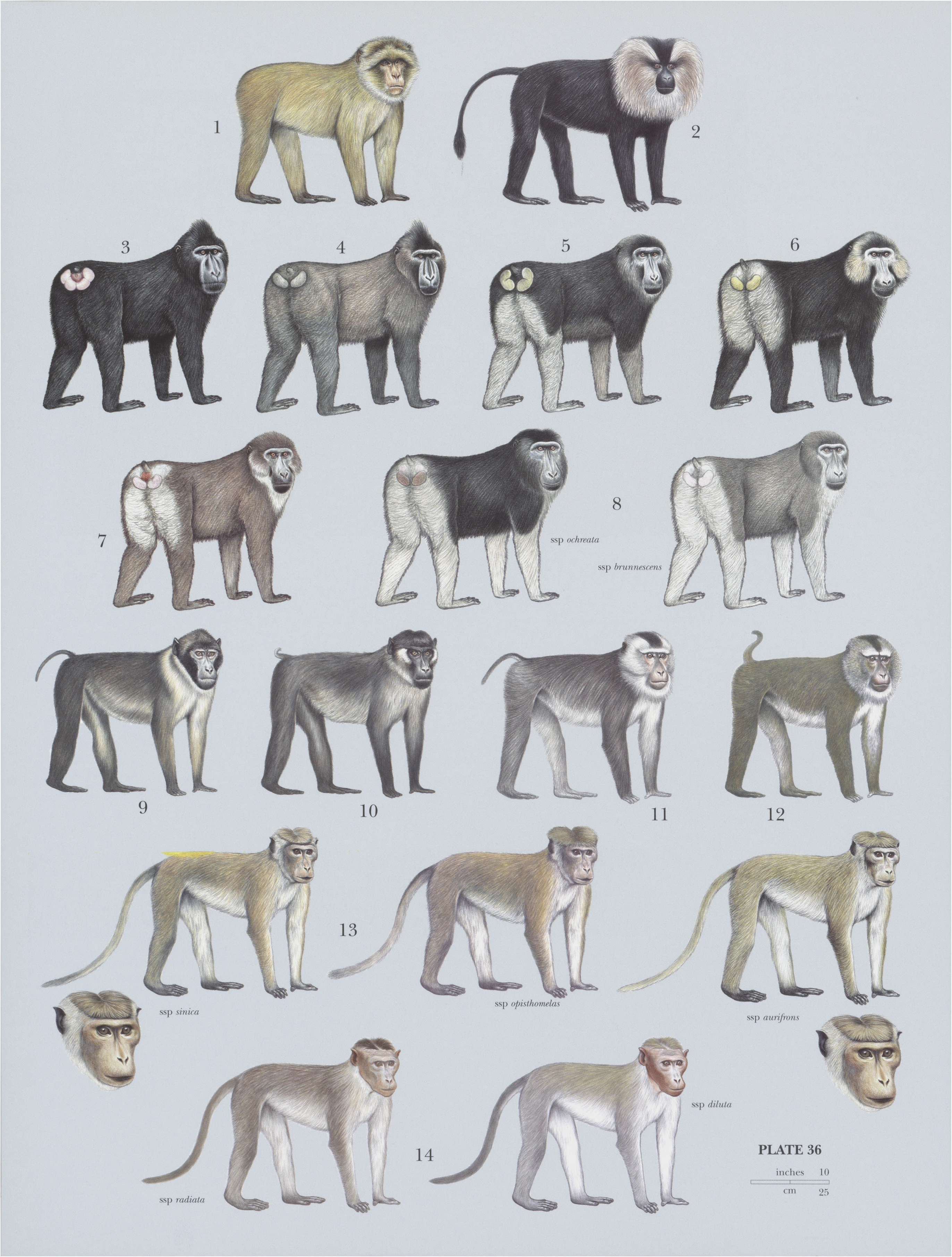

19. View Plate 36: Cercopithecidae

Long-tailed Macaque

Macaca fascicularis View in CoL

French: Macaque crabier / German: Java-Makak / Spanish: Macaco cangrejero

Other common names: Crab-eating Macaque, Longtail Macaque; Burmese Long-talied Macaque (aureus), Con Song Long-tailed Macaque (condorensis), Dark-crowned Long-tailed Macaque (atriceps), Kemujan Long-tailed Macaque (karimondjawae), Lasia Long-tailed Macaque (/asiae), Maratua Long-tailed Macaque (tua), Nicobar Long-tailed Macaque (umbrosus), Philippine Long-tailed Macaque (philippinensis), Simeulue Long-tailed Macaque (fuscus)

Taxonomy. Simia fascicularis Raffles, 1821 ,

Indonesia, Sumatra, (Bengkulu).

The M. fascicularis species group of macaques, including M. fascicularis , M. mulatta , M. cyclopis , and M. fuscata , is differentiated primarily on the shape of the male genitalia. In M. fascicular, the apex of the glans penisis bluntly bilobed, and the breadth of the glans is 41-55% of its length. The fascicularis species group has alternately been defined as including only M. fascicularis and M. arctoides . Ten subspecies are recognized based on complete (or nearly complete) discontinuity in variation of the same characters in the nominate species, M. f. fascicularis : color of dorsal pelage, crown, or outer thigh; lateral facial crest pattern; head-body length in adult males; and relative tail length of adult males. M. fascicularis is parapatric or marginally sympatric with M. mulatta for ¢.2000 km from south-eastern Bangladesh, west-central Thailand, and southern Laos to central Vietnam (c.15-20° N). Intermediate tail length and possibly noticeable geographic variation in dorsal pelage color, lateral facial crest pattern, head-body length, and skull length suggest hybridization in the latter three regions. All these characters in M. fascicularis north of the Isthmus of Kra (c.10° N) tend to be intermediate between those in M. fascicularis south of the Isthmus and those in M. mulatta . Y-chromosomes of M. mulatta have spread at least 400 km south to c.12-5° N within the distribution of M. fascicularis . The subspecies aureus has a contact zone with the nominate form fascicularis in the eastern and southern parts of the Isthmus of Kra and may intergrade also with the nominate form or M. mulatta in central and eastern parts of the Indochinese Peninsula. A contact zone between the subspecies philippinensis and fascicularis inhabited by mixed-phenotypic populations occurs in eastern and central Mindanao, southern Negros, and possibly nearby islands in the Philippines. Ten subspecies recognized.

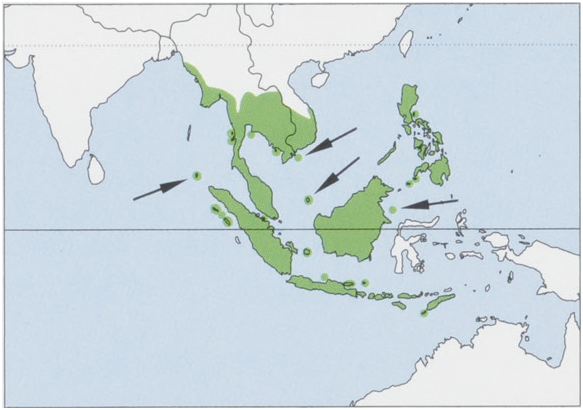

Subspecies and Distribution.

M. f. fascicularis Raffles, 1821 — S Laos, S Vietnam, Cambodia, E & S Thailand (and offshore Is), S to the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Sumatra, Java, Bali, and most but not all offshore Is, also extending into the Sulu Archipelago and Zamboanga Peninsula of W Mindanao, in the Philippines; probably artificially introduced in the Nusa Penida-Timor Is chain.

M. f. atriceps Kloss, 1919 — Ko Khram I (= Khram Yai), off SE coast of Thailand.

M. f. aureus E. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1831 — SW Bangladesh (Teknaaf Peninsula), S Myanmar (including the Mergui Archipelago), WC Thailand (S to ¢.10° N), and Laos. M. f. condorensis Kloss, 1926 — SE Vietnam (Con Son and Hon Ba Is in the South China Sea).

M. f. fuscus G. S. Miller, 1903 — Simeulue I, off NW Sumatra.

M. f. karimondjawae Sody, 1949 — Karimunjawa I and presumably nearby Kemujan I, N ofJava.

M. f. lasiae Lyon, 1916 — Lasia I, off NW Sumatra.

M. f. philippinensis 1. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1843 — Philippine Archipelago N of ¢.10° N. M. f. tua Kellogg, 1944 — Maratua I, off E Borneo.

M. f. umbrosus G. S. Miller, 1902 — Nicobar Is (Katchall, Little Nicobar, and Great Nicobar Is). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 37-63 cm (males) and 31.5-54.5 cm (females), tail 36— 71-5 cm (males) and 31:5-62.8 cm (females); weight 3.4-12 kg (males) and 2.4-5.4 kg (females). The Long-tailed Macaque is the smallest of the fascicularis species group. Adult males are generally larger than adult females; mean head-body length of males exceeds that of females by 13%. Geographic variation in dorsal pelage coloration is noticeable, ranging from buffy to yellowish-gray to golden brown to reddish brown to dark brown to blackish. Erythrism of dorsal pelage varies in intensity in different regions. Crown is usually more brightly colored than the back. Crown hairs are directed backward and outward, sometimes forming a small, pointed central crest or, alternately, a darker cap. Outer surfaces of limbs fade from about the same color as the adjacent area of the trunk to pale grayish to pale golden brown at wrists and ankles. The dorsal surface ofthe tail is darker at the root (golden-brown or blackish) and gets progressively paler toward the tip. Pelage on under surfaces of trunk, limbs, and tail is thin and pale gray to whitish. Thinly haired facial skin is brownish to pinkish with sharply defined whitish upper eyelids (although hair may be concentrated on the upperlip or chin). Cheek whiskers usually sweep upward from near the angle of the jaw to the outside margin of the crown between the eyes and ears (transzygomatic crest pattern); less frequently, in some populations (or individuals), the crestis restricted to the posterior region of the lowerjaw (infrazygomatic cheek pattern). All dorsal pelage of newborn infants is conspicuously dark brown to blackish. Infant facial skin is bare, lacking pigment, and pinkish.

Habitat. Preferred habitats include seashore, along with mangrove forest, riverbanks and swamp forest, most commonly found at low elevations but up to ¢.2000 m above sea level. A 1996-1999 survey in west-central Sumatra found Long-tailed Macaques only in lowland and hill dipterocarp forests at elevations of less than 800 m. They can live successfully in edge habitats and are often found near human settlements in fields, botanical gardens, plantations, temple precincts, fruit orchards, and vegetable gardens. Some populations may invade human habitation in search of food. Dependence on human sources of food is widespread in Thailand, and the only natural populations there may be confined to the Western Conservation Corridor, specifically Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary in Uthaithani Province.

Food and Feeding. Long-tailed Macaques are opportunistic feeders, omnivorous but primarily frugivorous. They consume leaves and other plant parts, invertebrates (crustaceans, bivalves, and snails near water and insects inland) and small vertebrates (fish). On the seashore, they select and transport rocks to crack open oysters to eat. Loss of forest habitat may result in crop raiding of rice and corn in rural areas and scavenging (and begging) for food in urban areas.

Breeding. Seasonal peaks in copulations, pregnancies, and births occur among populations of Long-tailed Macaques, but timing varies geographically and between years at the same locality—apparently associated with fruiting cycles. Single birth occurs after a gestation of 160-168 days. Females probably become reproductively active at c.3-5 years old, and their first infant may be born when they are c.4 years old. Males usually begin to copulate as subadults at 5-6 years old, after they have left their natal troop. The mean duration of the menstrual cycle in 28 captive females was 30-9 days. Prominent swelling of the bare skin between the root ofthe tail and anus occurs at puberty, and skin around the vulva frequently reddens. In post-pubertal females, sexual swelling and reddening are generally less conspicuous and are highly variable in size and duration. In a well-studied population in northern Sumatra, mating and consortships of most females tended to increase with increasing intensity of one of these characteristics. Mating may be initiated by either sex by staring at the other and usually continue with the male’s examination of the perineum of the female. The male mounts the female by gripping her hips with his hands and her calves with his feet. Ejaculation may occur either as a result of a single mount or multiple mounts. During a 4year period in northern Sumatra, overall annual birth rate (births/adult female) was 0-58. High and low birth rates tend to occur in alternate years in the wild, but captive females are capable of producing young every year. A non-provisioned female may produce c.8-9 offspring during her reproductive life (age c.4-20 years). In captivity, known maximum life span for the Long-tailed Macaque is 37 years. Mean birth weight in a large captive group was 318-2 g (+ SD 45-2 g) for 563 female infants and 347-5 g (+ SD 55-2 g) for 600 male infants. In captivity, nursing lasts 9-22 months, although 15 months appears to be average. Adult male infanticide may be one of the important causes of infant death. The gradual change from blackish neonatal pelage to adult coloration begins at 2-3 months of age when infants begin to obtain some of their food independently; the transition appears to be complete before the eruption of permanent first molars at c.15 months old.

Activity patterns. The Long-tailed Macaque is diurnal. It often forages on the ground in coastal and riparian areas; 25% of encounters in Sumatra and 26-5% in East Kalimantan Province (Indonesian Borneo). Feeding occupies 13-55% of daily walking hours. It is predominantly arboreal in inland forest, favoring the lower and middle forest strata; 98% in Peninsular Malaysia and ¢.97% in East Kalimantan. Tall, relatively bare trees near a river may be preferred sleeping sites. Groups of Long-tailed Macaques may flee from danger on the ground or in the canopy or both. They are excellent swimmers and apparently enter the water for pleasure.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Non-provisioned groups of Longtailed Macaques contain 5-100 individuals, although they may subdivide into smaller units to forage. Groups are multimale-multifemale, with resident lineages of female kin and males emigrating from their natal groups. Dominance/subordination hierarchies exist within and between lineages in females and among males. Known ratios of sexually mature males to sexually mature females are 1:0-58-7-1. Predator detection may be a major determinant of social behavior and group size. Home ranges are quite variable at 12-5 ha to more than 300 ha. Home range overlap is generally slight and encounters between adjacent groups are relatively rare, although home range of a “daughter group” may overlap extensively with that of her natal group. Reported mean daily movements are 325-1900 m and may be positively correlated with group size.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The [UCN Red Lust. Subspecies condorensis and umbrosus are classified as Vulnerable, philippinensis as Near Threatened, fascicularis as Least Concern, and atriceps, aureus, fuscus, karimondjawae, lasiae, and tua as Data Deficient. Populations of Long-tailed Macaques have been decimated in Bangladesh by shrimp farming and shipbuilding, and habitat availability and quality have been significantly reduced in Myanmar. Throughout much ofits distribution, especially that of the nominate form fascicularis , human-macaque conflict is burgeoning in both rural and, more recently, urban landscapes as human populations expand and forest habitat is encroached upon. Responses have included culling (Peninsular Malaysia), increased quotas for trapping of wild monkeys for domestic research as well as “breeding stock” for primate export companies (Indonesia), and sterilization (Singapore)—frequently in the absence of surveys and population estimates, or using questionable survey data. At the same time, wild populations suspected of having been laundered as captive-bred may be exploited for the international trade driven by industrial testing and biomedical research. According to the CITES database maintained by the United Nations Environment Programme-Wildlife Conservation Monitoring Centre (UNEP-WCMC), more than 254,000 live Long-tailed Macaques were exported for medical, scientific, commercial, and breeding purposes from 2004 until July 2010. Imports of Long-tailed Macaques into the USA—the world’s largest user of primates and, as such, a bellwether of pressure on wild populations—increased from 17,124 individuals in 2004 to 24,629 individuals in 2005 and reached 26,799 individuals in 2008. A recent decline in numbers imported into the USA may be associated with outsourcing. Participants in the open meeting at the 2008 Congress of the International Primatological Society (IPS) in Edinburgh, UK, to review the biennial listing of the “World’s 25 Most Endangered Primates ,” ajoint activity of the[IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group, Conservation International, and IPS, officially recognized the Long-tailed Macaque as the first “widespread and rapidly declining” primate species, and thelisting of the Long-tailed Macaque on The IUCN Red List is currently being reassessed.

Bibliography. Abegg & Thierry (2002a), Anonymous (2010), Aggimarangsee (1992), Bennett et al. (1986), Crockett & Wilson (1980), Duckworth et al. (1999), Eudey (1979, 1980, 1981, 1987, 1991, 1994, 2008), Fittinghoff & Lindburg (1980), Fooden (1971, 1976, 1991b, 1995, 2006), Groves (2001), Gumert et al. (2011), Hamada, Kawamoto, Kurita et al. (2009), Hamada, Kawamoto, Oi et al. (2009), Jadejaroen et al. (2010), Jintanugool et al. (1985), Khan et al. (1985), Kingsada et al. (2010), Lekagul & McNeely (1988), Lim Boo Liat (1969), Mack & Eudey (1984), Malaivijitnond et al. (2010), McGreal (2012), Medway (1972), Molur et al. (2003), Muroyama & Eudey (2004), Payne (1985), Rijksen (1978), Rodman (1973), San & Hamada (2010), San et al. (2009), Sandu (2010), Thao et al. (2010), Vietnam, Ministry of Science, Technology and Environment (1992), Wheatley (1980), Yanuar et al. (2009).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.