Macaca silenus (Linnaeus, 1758)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863139 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFC3-FFC7-FA35-6602F83AF421 |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Macaca silenus |

| status |

|

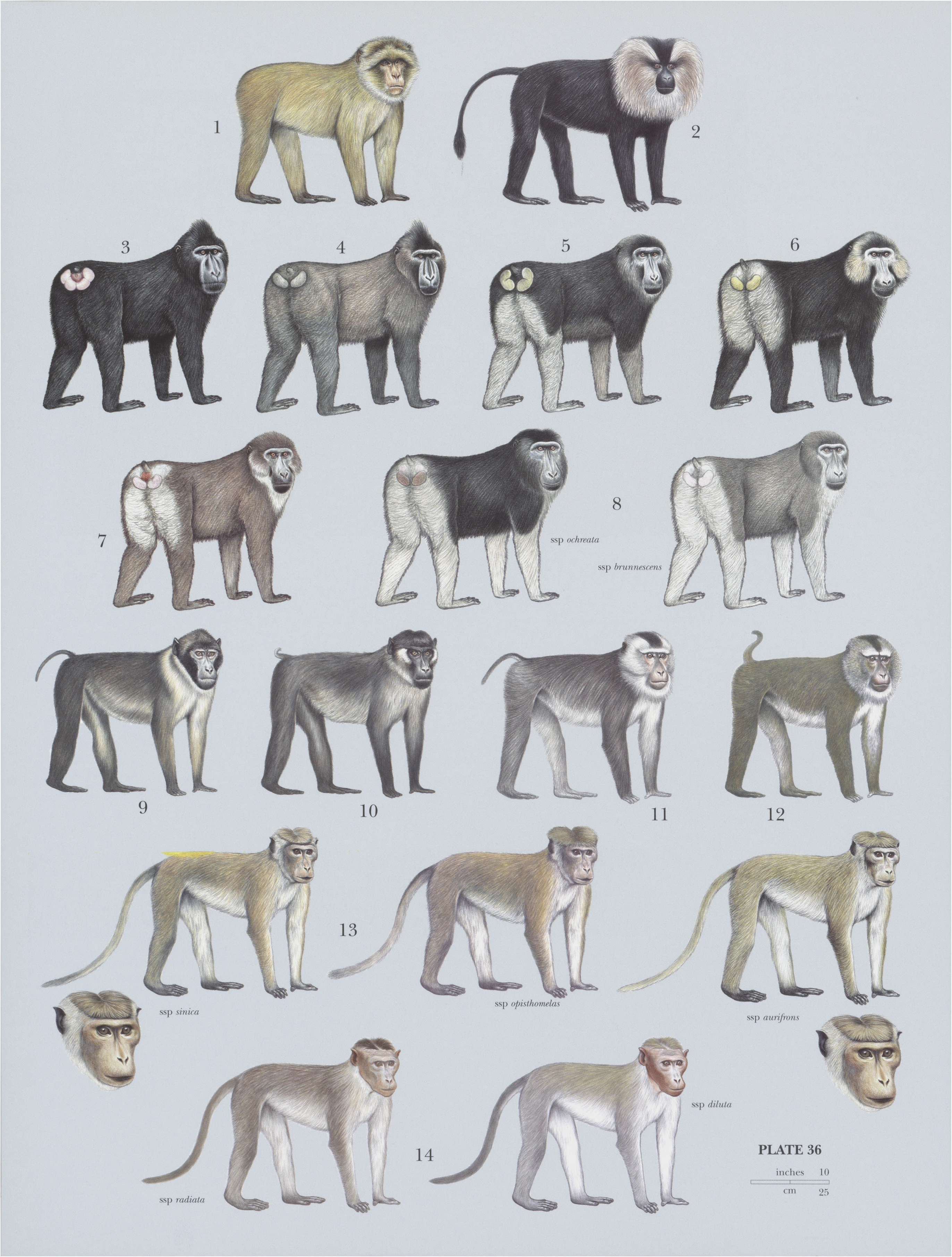

2. View Plate 36: Cercopithecidae

Lion-tailed Macaque

French: Macaque a queue de lion / German: Bartaffe / Spanish: Macaco de cola de len

Other common names: \ Wanderoo

Taxonomy. Simia silenus Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL ,

“Ceylon.” Corrected by J. Fooden in 1975 to India, Western Ghats, inland from Malabar coast.

M. silenus is a member of the silenus species group of macaques, with its phylogenetic sister species being M. leonina , and including M. siberu , M. nemestrina , M. pagensis , and the seven Sulawesi species. Monotypic.

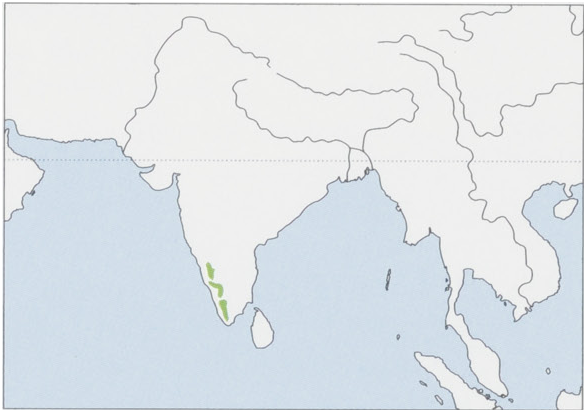

Distribution. SW India, endemic to the hills of the Western Ghats in the states of Karnataka , Kerala, and Tamil Nadu, stretching from Anshi Ghats in the N to the Kalakkad Hills in the S, at elevations of 800-1300 m. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 51-61 cm (males) and 42-46 cm (females), tail 24— 39 cm (males) and 25-32 cm (females); weight 5-10 kg (males) and 2-6 kg (females). Adult female Lion-tailed Macaques are ¢.33% smaller than adult males. The face is all black and surrounded by a large characteristic grayish-brown cheek and chin ruff. Fur is otherwise glossy black. The Lion-tailed Macaque is characterized by thin but strongly projecting supraorbital ridges and a flat broad nose. Eyes are closelyset, hazel, and complemented by large conspicuous eyelids contrasting with the dark face. Tailis 55-75% of the head-body length and has a tuft of hair at the end, like that of a Lion (Panthera leo). Tail is normally pendulous but is carried to one side or carried up during sexual displays and carried low when frightened or to show submission.

Habitat. Climax tropical evergreen and broadleaved monsoon forests (referred to regionally as “sholas”) with canopies reaching 30-50 m mostly at elevations of 100 1800 m. Lion-tailed Macaques are habitat specialists and broadly sympatric with the folivorous Nilgiri Langur (Semnopithecusjohnii). Close to the Arabian Sea, western slopes receive heavy south-west monsoons and up to 6000 mm of rain/year. Eastern slopes in the rain shadow are drier and typically have dry deciduous and scrub forests. Below 300-600 m, the forest grades into low-lying moist deciduous forest. Seasonally, Liontailed Macaques may enter forest at lower elevations, and they may use them more if they are not hunted. Above elevations of 1500-1800 m, vegetation grades into montane forest with a lower canopy. They spend most of their time in the forest canopy: 40% at 21-30 m above the ground and 26-5% at 11-20 m. In undisturbed climax forest, they are very rarely seen on the ground (just occasionally to eat mushrooms). Floristic composition differs between forests in the northern and southern parts of their distribution, probably affecting, subtly or otherwise, their diets and movements. The canopy of the northern forests ( Karnataka ) is abundant in Dipterocarpus (Diperocarpaceae) . In the south,it is frequently dominated by Cullenia exarillata ( Malvaceae ), a favored food species. In some areas, Lion-tailed Macaques are able to persist in human-modified landscapes: mosaics of degraded and secondary forest patches, home gardens, and tea and cardamom plantations. Their capacity to adapt to progressively degraded forest fragments was elegantly studied by M. Singh and coworkers in the Puthuthotum coffee/tea estate, one of many on the Valparai Plateau in the Anaimalai Hills in Tamil Nadu State. Forest fragments in the region were 5-15,000 ha, and each was occupied by 1-6 groups of Lion-tailed Macaques. In 2000, a forest patch under study totaled 102 ha, of which a part (68 ha) was underplanted with cardamom and another with coffee (32 ha). The forest had been selectively logged in 1989-1990 and 1997-1998, and in many areas, non-native planted and pioneer trees predominated. Climax native species had been lost. Canopy height had decreased (19 m in 1994 to 14 m in 2000), and the canopy was severely broken (cover in 1994 was 62% vs. 27% in 1999). Basal area of the forest trees (area of tree trunks at breast height) dropped from 67-2 m?/ha to 17-4 m?/ha from 1994 to 1999. In 2000, c.40% of the area had no mature trees, and lianas and vines were almost completely absent. Two groups of Lion-tailed Macaques occupied this forest, and group size increased from 1995 to 2000 despite major changes in structure and floral composition. One group grew from 36 to 51 individuals and the other from eleven to 17 individuals. Birth rates of both groups were | infant/2-4 female years (number of potentially reproductive females each year from 1996 to 2000). Lion-tailed Macaques adapted their diets and movements to these small forest patches and human modified landscapes. Compared with groups in undisturbed climax forest, they did not travel as far each day (averages of 1211 m and 734 m for the two groups compared with 1810 m for a group studied in tall forest). This was explained by a more clumped distribution of key food sources (many of them non-native and planted) of macaques in the disturbed areas. Lion-tailed Macaques wentto the ground to forage, even picking up large fallen fruits such as those of native jackfruit ( Artocarpus heterophyllus, Moraceae ) and Cullenia —a behavior never seen in tall forest. They also used the ground to travel through tea plantations to gain access to fruits and flowers of coffee, Lantana ( Verbenaceae ; invasive exotic), reach other forest patches, and even rest. Time spent in trees decreased from 95% in 1990 to 71% in 2000. The rate of encounters between groups increased from one encounter every eleven and a quarter hours of observation to one encounter every five and a half hours of observation in the same period. In great contrast with diets of groups in of tall-forest, nearly 40% of the plant part of the diet involved cash crops and non-native and introduced pioneer species. The majority of the cash crop part of the diet was the mesocarp and seeds of coffee, and the incidence of coffee bushes in the forest understory resulted from macaques dispersing seeds. With the more broken canopy in the modified forest, the rate at which macaques fell out of the trees was very high (1-5 incidents/day). An evident effect of the forest fragmentation—the lack of any arboreal connection with other forests—was a reduced bias toward females in the adult sex ratio, because males were unable to disperse. Adult sex ratios in larger forests with multiple groups can be as high as 1:9-9, but the two groups at Puthuthotum had sex ratios of 1:4-6. A very large part of the remaining habitat for the Lion-tailed Macaque comprises such forest patches in human-dominated landscapes, and their capacity to adapt to them is the reason they are not on the verge of extinction.

Food and Feeding. The Lion-tailed Macaque is primarily frugivorous; fruit forms the major portion of its diet, supplemented with seeds, young leaves, berries, and nuts. Fruits of Artocarpus and fruits and flowers of Cullenia exarillata are important foods that are available throughout the year. Fruits of Palaquium ellipticum ( Sapotaceae ), Fugenia ( Myrtaceae ), Elaeocarpus munroii (Elacocarpaceae), Vepris biloculars ( Rutaceae ), and Viburnum acuminatum ( Caprifoliaceae ), and flowers of Loranthus (Loranthaceae) are also important in the diet in most months of the year. A number of species are important seasonally, including, for example, Syzygium mundagam ( Myrtaceae ), Lailsea wightiana ( Lauraceae ), and fruits of the palm Bentinckia condapanna ( Arecaceae ). Lion-tailed Macaques also eat bark, nectar, gums, and a variety of invertebrate and vertebrate prey. Fungi and lichens are eaten occasionally, and when close to villages, they eat cultivated fruits such as guava, passion fruit, coffee, and those of the exotic umbrella tree ( Maesopsis eminii, Rhamnaceae ), used to shade the coffee. Invertebrates and vertebrates comprise ¢.20% of the diet (proportion of time spent feeding on different items). The faunal component of the diet is higher in the dry season (24%; December—-May) when fruit is scarce than in the wet season (11%; June-November) when fruit is more abundant. They eat mostly invertebrates, including orthopterans, leaf insects ( Phyllidae ), and stick insects (phasmids) gleaned from the foliage and leaf litter, along with spiders picked out of their webs (communal spiders; the macaques mess with the web to scatter them and then pick them off one by one), moths and butterflies, cicadas, and dragonflies (eaten head first; wings and legs discarded), Hymenoptera and Isoptera (emerging adult forms), and caterpillars (if on a leaf, they are cajoled to a hard surface and then rubbed to remove anything extradermal—stinging hairs, stings and spines—before eating). They will eat secretions of the nest and eggs of tree frogs (Rhacophorus) and the tree frogs themselves (eaten by all ages and both sexes). Adults also eatlizards of the genera Calotes (tree lizards) and Draco (flying dragons), both in the family Agamidae . Lizards are killed by a bite to the head and eaten, head first, but without ingesting the skin and bones. Birds, nestlings, and bats are also eaten. They have been to seen to attack and severely injure the fawn of an Indian Chevrotain (Moschiola indica ); it escaped and was chased, without success, by the alpha male. In certain areas, local people wrap placentas of cows in a cloth and hang them from a branch, and Lion-tailed Macaques have been seen to rip open the bundle and eat the entire placenta.

Breeding. Lion-tailed Macaques breed throughout the year but with a birth peak in February-March. The menstrual cycle is ¢.40 days. Females are sexually mature at around four years old. Males begin to breed when they are c.8 years old. Receptive females exhibit a conspicuous small perianal swelling. Females first give birth typically at 6-5 years old, and interbirth intervals have been recorded as 20 months in captivity, 23 months in a group monitored in a forest fragment in a tea plantation, and 30 months in groups in extensive rainforest habitat. The gestation period is 162-186 days. Neonates have brown fur and pale pink skin and are nursed for c.12 months. Infants are weaned at 5-5-9 months. Any nipple contact post-weaning is reciprocated with punishment by the mother. Mothers invest greater parental care and interest toward male infants than female infants. Male infants are groomed twice as much as female infants. Individuals can live up to 38 years.

Activity patterns. Lion-tailed Macaques are diurnal and the most arboreal of the species of macaques. Foraging for food and eating take up a little more than half of their day. They rest for ¢.27% of the time, travel for c.15%, and interact socially (mating, play, allogrooming, and agonistic interactions) for ¢.3-5%. They show no distinct seasonal patterns in activity. In cooler weather or at higher elevations, they spend more time foraging and less time resting.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Lion-tailed Macaqueslive in groups of 4-30 individuals, usually 10-20, but at least one group in a forest fragment on a tea plantation in the Anaimalai Hills had more than 50 individuals in 2001 and 84 in October 2005. This extraordinarily large group and its exceptional increase in size were attributed to high infant survival (only one of 37 infants born in 2002-2005 died) in the absence of hunting and with an abundance of cultivated fruits and commercial crops (e.g. coffee). Groups typically have 1-3 adult males and about twice the number of females, besides subadults, juveniles and infants. Ratios of adult males to adult females can be as high as 1:9-9. There is a high rate of male movement among groups; females are philopatric. Male entry into other groups generally involves an aggressive takeover of the resident male rather than discretely entering the hierarchy and working one’s way up (as is typical of the Rhesus Macaque, M. mulatta , and the Japanese Macaque, M. fuscata ). Male Lion-tailed Macaques in a group tend to maintain their distance from each other compared with, for example, Bonnet Macaques ( M. radiata ) that are friendly, huddle a lot, and spend much of their time in close proximity. Male-male relationships in Lion-tailed Macaques tend be more agonistic than affiliative, and the male dominance hierarchy is strongly linear (much more so than in Bonnet Macaques). Selective pressures hinge on the fact that male Lion-tailed Macaques breed throughout the year, which results from the relative lack of seasonality in food availability. A male, as such, is able to defend his access to females (one or two receptive at any one time), which is otherwise difficult if the breeding season is very short with all females becoming sexually receptive over a short period, as happens in Bonnet Macaques. Short studies (two months or so) have indicated home range sizes of ¢.200 ha, but over longer periods, groups gradually change and expand their home ranges, which can extend to 500 ha or more. There is considerable overlap among home ranges of neighboring groups, but in a 500ha home range, the central core area of ¢.300 ha is rarely entered by other groups. Their large home ranges are related to the fact that they are selective feeders, depending on relatively few and widely dispersed food resources. Home ranges are smaller in fragmented forests next to plantations where food resources are more concentrated. Under natural circumstances, larger mammalian predators such as Leopards (Panthera pardus), Dholes (Cuon alpinus), and pythons (Python) are not a problem for Lion-Tailed Macaques because they so rarely go to the ground; however, they do mob them. Predators likely include the Indian black eagle (Ictinaetus malayensis) and the mountain hawk-eagle (Spizaetus nipalensis). Dogs are predators in humanmodified landscapes where Lion-tailed Macaques are more terrestrial.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red Last. Lion-tailed Macaques are offered the highest protection under Schedule 1, Part I, of the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act of 1972. In the late 19" and early 20™ centuries, large tracts of the forests of the Western Ghats were cleared for cultivation of rice, tea, cardamom, coffee, eucalyptus, and teak. Commercial crops such as Areca nuts and rice were even cultivated inside protected areas. Illegal settlement on reserved forests causes damage because of harvesting of non-timberforest products and the collection of firewood. Development projects such as dams (power generation and irrigation), mining and mineral exploration, road construction, and power lines threaten forests and the survival of the Lion-tailed Macaque. Today, these macaques are divided into three subpopulations. The most southerly occupies forest fragments in the Anaimalai Hills, to the south of a natural divide in the Western Ghats, the Palghat Gap in Kerala. To the north of the Palghat Gap, Lion-tailed Macaques are divided to two subpopulations due to their extirpation by hunting in the Coorg District of Karnataka . The most northerly subpopulation occurs in the region of Sirsi-Honnavara in Uttara Kannada District, Karnataka . Hunting (guns and traps) for food, traditional medicine, and the pet trade are also local but insidious threats. In 1968, it was believed that numbers of Lion-tailed Macaques in the wild did not exceed 1000 individuals. Surveys conducted in the mid-1970s recorded an all time low ofjust 400 macaques. In 2002, however, new and significant populations were discovered in the north ofits range, notably in the region of Sirsi-Honnavara in Karnataka , with an estimated 32 groups (790 individuals). This region is in need of protection and management. Protected areas in Karnataka are heavily hunted, and local extinction is probably inevitable if proper measures are not adopted. The total population of Lion-tailed Macaques in the wild is now estimated to be less than 3500-4000 individuals in 47 isolated populations, each having no more than 250 mature individuals. Mature individuals in the wild number less than 2500. About 1216 adult Lion-tailed Macaques have been reported in Kerala. In the Anamalai Hills of Tamil Nadu, ¢.500 individuals exist in two subpopulations of 7-12 groups. Lion-tailed Macaques occur in a number of protected areas, including Indira Gandhi Wildlife Sanctuary and National Park, Kalakkadu Wildlife Sanctuary, Kudremukh National Park, Periyar Wildlife Sanctuary, and Silent Valley National Park.

Bibliography. Abegg et al. (1996), Ali (1985), Ananda Kumar et al. (2001), Bhat (1984), Clarke et al. (1992, 1993), Easa et al. (1997), Fooden (1975), Ganesh & Davidar (1997, 1999), Green & Minkowski (1977), Harvey et al. (1991), Heltne (1985), Karanth (1985, 1992), Krishna, Singh & Kaumanns (2008), Krishna, Singh & Singh (2006), Kumar (1987, 1995), Kumar & Kurup (1981), Kumara & Singh (2004, 2008), Kurup (1978), Kurup & Kumar (1993), Lindburg (1980), Menon & Poirier (1996), Molur et al. (2003), Ramachandran (1998), Roonwal & Mohnot (1977), Singh, Ananda Kumar et al. (2002), Singh, Jeyaraj et al. (2011), Singh, Kaumanns et al. (2009), Singh, Kumara, Ananda Kumar & Sharma (2001), Singh, Kumara, Ananda Kumar, Sharma & Defalco (2000), Singh, Singh et al. (1998), Sugiyama (1968), Sushma & Singh (2006), Umapathy & Kumar (2000), Ziegler et al. (2007), Zinner, Hindahl & Kaumanns (2001).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.