Nezara, Amyot & Serville, 1843

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ doi:10.11646/zootaxa.2424.1.1 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/5347AD2B-FFD4-E875-EDCD-FF5052D1A996 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Nezara |

| status |

|

The genus Nezara View in CoL View at ENA

The revision work of Freeman (1940) established the current classification of the genus, including 11 valid species in Nezara : N. antennata , N. immaculata Freeman, 1940 , N. frontalis ( Westwood, 1837) , N. naspirus ( Dallas, 1851) , N. niamensis ( Distant, 1890) , N. orbiculata ( Distant, 1890) , N. robusta Distant, 1898 , N. similis Freeman, 1940 , N. soror Schouteden, 1905 , N. congo Schouteden, 1905 [synonymized to N. robusta by Freeman (1946)], and N. viridula . Linnavuori (1972) redescribed two species not included by Freeman (1940): N. mendax Breddin, 1908 and N. subrotunda Breddin, 1908 . After studying the type specimens of both species, we now consider N. mendax to be a valid species and N. subrotunda to be a junior synonym of N. naspira ( Dallas, 1851) . Zheng (1982) added the last known species to the genus, N. yunanna , from Duanli, Yunnan, based on 5 male and 2 female specimens deposited in the Nankai University, Tianjin, China.

At least seven other species are assigned to Nezara in the literature. Four of them were considered incertae sedis, two are transferred to different genera, and one is considered a junior synonym, as follows. Nezara griseipennis Ellenrieder, 1862 , and N. raropunctata Ellenrieder, 1862 were considered as incertae sedis by Stål (1876). However, they were listed in Lethierry & Severin (1893) and Kirkaldy’s (1909) catalogs. These species were described from Indonesia (Sumatra), and Indonesia (Java) respectively and the deposition of the types are unknown. In all collections studied, we have not examined any specimens with the characteristics described for these species. As such, we follow Stål (1876) in considering them as incertae sedis.

Distant (1902) described Nezara nigromaculata from Ceylon [ Sri Lanka]. Syntypes were deposited at BMNH. Digital photographs of these specimens were sent by the curator of BMNH collection, Dr. Mick Webb. From the examination of these photographs, we conclude that N. nigromaculata does not share the synapomorphies of Nezara . Thus, we transfer this species to the genus Acorsternum.

Breddin (1903) described N. pulchricornis from Fernando Po [= Bioko], Equatorial Guinea. He compared his species with Nezara fieberi Stål, 1865 which is now included in the genus Chinavia . Dr. Eckhard Groll, curator of SDEI collection, sent us digital photographs of the lectotype and of the following labels of N. pulchricornis : a) Holotype b) coll. Breddin / Typus / Fern. Po S. Isabel / Schouteden det. 1936 c) G. Schmitz det. 1982 [male] Acrosternum varicorne (Dallas) ? Gaedike (1971) referred to this specimen as the holotype, but this is actually an inadvertent lectotype designation (Rider, personnal communication). Apparently, Schmitz conclusions were never published. From the examination of these photographs, we conclude that N. pulchricornis does not share the synapomorphies of Nezara . Thus, we transfer this species to the genus Chinavia .

Nezara paradoxus Cachan, 1952 , was described based on a single male specimen collected in Tananarive, Madagascar Center, which was supposed to be deposited at MNHN. But the holotype was not located by CFS (second author) during a visit to that collection in 2003. Cachan’s description does not permit recognition of this species as a distinct taxon within Nezara . Consequently, we consider it to be incertae sedis.

Nezara antennata var. icterica Horvath, 1889 , was upgraded to species by Ghauri (1972), based on the distinct morphology of the parameres. The male lectotype of N. antennata var. icterica , deposited in the Hungarian Natural History Museum (HNHM) was studied from a digital image sent by Dr. D. Rédei. Dr. Rédei also sent the data from the lectotype and the 3 paralectotypes labels: a) Himalaya \ Plason b) Nezara [male]\ antennata Scott \ var. icterica Horv. c) Lectotype d) G. Schmitz det. 1984 \ Nezara viridula (L.) \ [male]. Paralectotype female a) Japonia \ Xántus b) 1 c) Nezara \ antennata Scott \ var. icterica Horv d) Paralec- \ totype \ [female] a) C. Schmitz det. 1984 \ Nezara viridula (L.)\(f. viridula ). Paralectotype female: same labels as the above specimen. Paralectotype female: a) Japonia \ Xántus b) Paralec- \ totype \ [female] c) Nezara antennata \ Scott, var. \ icterica nov. \ G. Horvath 1889 d) C. Schmitz det. 1984 \ Nezara viridula (L.) \ (f. viridula ). He also mentioned that although the specimens were labelled lectotype, and paralectotype, apparently these designations were never published. Taking into acount the general aspect of the male specimen and the form of paramere, we agree with G. Schmitz that this variety is conspecific with N. viridula . Also, Dr. Rédei sent similar data for Nezara antennata var. balteata Horvath, 1889 : a) Japonia \ Xántus b) 1 c) Nezara \ antennata Scott \ var. balteata Horv. d) Lectotype \ [male] e) C. Schmitz det. 1984 \ Nezara viridula (L.) \ f. torquata (F.). Wu (1933) synonymized N. antennata var. balteata with N. antennata . In order to confirm the identity of this variety, we sent to Dr. Rédei illustrations of the pygophore of Nezara species. He disagreed with Schmitz's identification, by the form of the paramere clearly having a long, finger-like process, similar to that of N. antennata ( Zheng 1982, fig. 2). Therefore, we agree with Wu (1933) and treat this variety as a junior synonym of N. antennata .

Nezara indica Azim & Shafee, 1978 was described from six female specimens collected at the University Botanical Garden, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh, India, and was deposited at the Aligarh Muslim University. Efforts to obtain this material were unsucessful. According to the original description of this species, it is similar to N. similis , differing by the long abdominal median tubercle surpassing the metacoxae. Another character mentioned was the presence of a tranverse impunctate band on the pronotum. Based on these characters, we conclude that this species does not share the synapomorphies of Nezara , and we consider it incertae sedis.

Description of characters

Thorax

Character 1. Pronotum, lines of punctures: (0) absent; (1) present. ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

Transverse, parallel lines of punctures, concolorous or olive green to yellow, are found on the pronotum of some species. ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 D–F View FIGURE 1 ). The lines may also be present on the scutellum and hemelytra. Freeman (1940) described the dorsal surface of N. niamensis and N. robusta as having a whitish-yellow background streaked with green, corresponding to the lines here described.

Character 2. Corium, basal third: (0) straight, not surpassing an imaginary line tangential to the humeral angles; (1) convex, surpassing an imaginary line tangential to the humeral angles ( Fig. 3A View FIGURE 3 2 View FIGURE 2 ). ci=100/ ri=100. Unambiguous.

The general form of body can be ovate ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 BC) or elongate ( Fig.1 View FIGURE 1 A–F View FIGURE 1 ). Species with an ovate body have the connexivum well exposed and the basal third of the corium convex, surpassing an imaginary line tangential to the humeral angles. Concerning the independence of this character, see comments in Character 8.

Character 3. Ostiolar ruga: (0) ruga long with anterior margin straight and apex rhomboid ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N C View FIGURE 3 ); (1) ruga auriculate, conspicuous; (2) ruga auriculate, inconspicuous ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N E View FIGURE 3 ); (3) ruga long with anterior margin curved and apex pointed ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N D View FIGURE 3 ). ci=60/ri=60. Ambiguous.

The morphology of ostiolar ruga is variable among Pentatomidae . The limits of Nezara and related genera were established by previous authors based on the length of ostiolar ruga ( Stål 1872, 1876; Kirkaldy 1909; Bergroth 1914; Freeman 1940). The cuticular folding and the extension of the ruga along the anterior margin of the metapleura has also been used by many authors in phylogenetic studies ( Gapud 1991; Grazia 1997; Barcellos & Grazia 2003; Forte & Grazia 2005). Gapud (1991) considered plesiomorphic a short ruga, not reaching the middle of metapleuron, because it is the common condition in most Pentatomomorpha. However, Gapud based his decision in a priori method for the determination of character polarity, a view that is not in accordance with the use of the cladistic methodology ( Cassis & Schuh 2009).

Following the outgroup method of Nixon & Carpenter (1993), the plesiomorphic state is characterized by the anterior margin of ruga straight, with rhomboid apex ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N C View FIGURE 3 ); in derived states 1 and 2, the form of the ruga are similar, but the ostiolar opening distinct ( Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 E View FIGURE 13 ). The state 3 corresponds to an anteriorly curved ruga with pointed apex ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N D View FIGURE 3 ). Freeman (1940) characterized N. orbiculata and N. capicola as having rugae long with the apex pointed, and the remaining having auriculate rugae. Although N. soror has auriculate rugae, it is reduced in relation to the other two species; it also has a pointed apex, therefore it is here codified as state 3 ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N D View FIGURE 3 ).

Character 4. Opening of odoriferous glands: (0) completely visible in ventral view, opening semi-ellyptical ( Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 D View FIGURE 13 ); (1) partially visible in lateral view, opening circular ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N E View FIGURE 3 ). ci=50/ri=0. Ambiguous.

The opening of the odoriferous glands can be ellyptical, easily seen in ventral view (species with long ruga and/or conspicuously auriculate) (e.g. Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N D View FIGURE 3 ). The apomorphic state is characterized by the ruga partially covering the scent gland opening, being visible only in lateral view ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N E View FIGURE 3 ).

Character 5. Metapleural evaporative area: (0) occupying more than half of the metapleura ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N D View FIGURE 3 ); (1) occupying less than half of the metapleura ( Fig.3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N E View FIGURE 3 ). ci=50/ri=50. Unambiguous

Metapleural evaporative area varies in extension, from restricted to an area around the opening to well developed occupying more than half of the metapleura. This character has been used by previous authors in phylogenetic analyses with distinct taxonomical levels ( Gapud 1991; Hasan & Kitching 1993; Campos & Grazia 2006).

Character 6. Green hemelytral veins: (0) absent; (1) present. ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous. Hemelytral veins may be greenish, especially when the membrane is observed with white paper placed below the membrane.

Abdomen

Character 7. Median tubercle on urosternite III: (0) absent; (1) present. ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

The presence or the form of a median tubercle on urosternite III has been used by several previous authors, mainly to identify genera and species ( Atkinson 1888; Cachan 1952; Gross 1976; Rolston & McDonald 1981; Linnavuori 1982). Freeman (1940) distinguished at least three states in his key of Nezara species. In phylogenetic analyses, the presence of this tubercle (e.g. Gapud 1991; Campos & Grazia 2006) or the form of its apex (e.g. Grazia 1997; Fortes & Grazia 2005) were also used as characters. We consider the variation in form of the tubercle exhibits continuous variation among the species, making it difficult to define discrete states. Therefore, the presence of the median tubercle was codified as a derived state. In the group studied, only Nezara has the derived state, but a median tubercle could be present in other genera of the Nezara group (e.g. Chinavia Orian , Porphyroptera China, 1929 , Neoacrosternum Day, 1965 ). In N. orbiculata , the median tubercle is longer than in the remaining species of Nezara ( Fig. 3A View FIGURE 3 ).

Character 8. Connexival segments IV to VII, dorsal view: (0) obscured by hemelytra; (1) exposed ( Fig. 3A View FIGURE 3 2 View FIGURE 2 ). ci= 100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

Connexiva not obscured by hemelytra are usually found in species with more oval body, which imply in a broader abdomen (see diagnoses of the species).

Even though characters 2 and 8 are related to the oval body shape found in N. orbiculata and N. soror , both characters described modifications of different body structures: the convexity of the basal third of corium (character 2), and the expansion of abdominal width (characters 8). Thus, such consideration supports the independence of the characters in a topological point of view.

Character 9. Spiracular maculae: (0) absent; (1) less than twice the diameter of the spiracles; (2) more than twice the diameter of the spiracles diameter. ci= 66/RI=66. Ambiguous.

A green macula juxtaposed next to each spiracles may be present and may vary in size. Schwertner (2005) described this character, and codified it as present in Pseudoacrosternum cachani Day , N. orbiculata and N. viridula . Here, we also codified it as present in Aethemenes cloris .

Character 10. Margins of body (pronotum, hemelytra and connexiva): (0) red band absent; (1) red band present ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 D–F View FIGURE 2 ). ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

A red band, sometimes extending to the head, may be present around the outer margin of the body. The band may be reduced, or absent in some areas. Schwertner (2005) used this character and codified it as present in Neoacrosternum rufidorsum (Breddin) and most Chinavia species included in his analysis of the Nezara group; this character was homoplastic, with reversals in some of the clades.

Character 11. Urosternite VII in females: (0) posterior margin arcuate, not elevated in relation to the placement of genital plates; (1) posterior margin strongly arcuate ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 B View FIGURE 16 ), well elevated in relation to the placement of genital plates. ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

According to Baker (1931) there is a trend in the development of the genitalia of both male and female: the more caudal the opening of the female genitalia, the more posterior the opening of the genital cup in males. This is true in Nezara species; the gonocoxites 8 are almost perpendicular to the sagital plan. This configuration is not observed in any of the outgroup taxa.

Character 12. Spiracles on laterotergites 8: (0) visible in more than half of its diameter; (1) totally obscured ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 A View FIGURE 16 ), or less than 1/3 visible ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 D View FIGURE 16 ). ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

The spiracles could be partially or totally obscured by the posterior margin of urosternite VII.

Female genitalia

Character 13. Laterotergites 9, shape: (0) uniformly flat; (1) basal half concave ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 B–C View FIGURE 16 ); (2) basal half laterally concave and convex at middle margin ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 E–F View FIGURE 16 ). ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

Fortes & Grazia (2005) considered the length of laterotergites 9, compared with the length of the laterotergites 8 as a character; they also studied the form of the apex of laterotergites 9. Schwertner (2005) analyzed the surface of basal half of the laterotergites 9 (flat or concave), and pointed out that the strongly concave basal half was a synapomorphy of Nezara . We have coded three states for this character, since in N. naspira the surface is concave but could have a callus well developed on middle margins, obscuring the concave area. ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 E View FIGURE 16 ).

Character 14. Gonocoxites 8, longitudinal sutures: (0) absent; (1) shallow sutures not attaining apical margin of urosternite VII ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 C View FIGURE 16 ); (2) deep sutures attaining apical margin of urosternite VII ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 F View FIGURE 16 ). ci=50/ ri=66. Ambiguous.

Length of gonocoxites 8 in relation to other genital plates was used by Grazia (1997); form of posterior margin by Fortes & Grazia (2005), Grazia (1997) and Schwertner (2005). The presence of longitudinal sutures near the posterolateral angles is here used for the first time. The Nezara species, except N. orbiculata , have the longitudinal sutures.

Character 15. Gonocoxites 9, 1+1 concave areas: (0) absent; (1) present. ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous. Gonocoxites 9 may have 1+1 concave areas near posterior margins of gonocoxites 8, resulting in a central area weakly elevated ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 A–C View FIGURE 16 ).

Character 16. Gonapophyses 8, discal area: (0) totally exposed, sub-retangular, sutural margins of gonocoxites 8 parallel, not juxtaposed ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 E View FIGURE 16 ); (1) partially obscured, triangular at basal half, sutural margins of gonocoxites 8 straight at base, juxtaposed at apical half ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 H View FIGURE 16 ); (2) partially obscured, triangular at basal half, sutural margins of gonocoxites 8 concave at base, juxtaposed at apical half ( Fig.16 View FIGURE 16 F View FIGURE 16 ). ci=66/ri=75. Ambiguous.

Discal area of gonapophyses 8 may be exposed or obscured by gonocoxites 8. Limits and form of sutural margins of gonocoxites 8 (divergent at base and juxtaposed on apical half or parallel, not juxtaposed) determine the extension and form of the exposed discal area of gonapophyses 8.

Character 17. Gonocoxites 8, posterior margins: (0) sinuous near sutural angles ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 E View FIGURE 16 ); (1) straight ( Fig. 10 View FIGURE 10 L View FIGURE 10 ). ci=50/ri=80. Ambiguous.

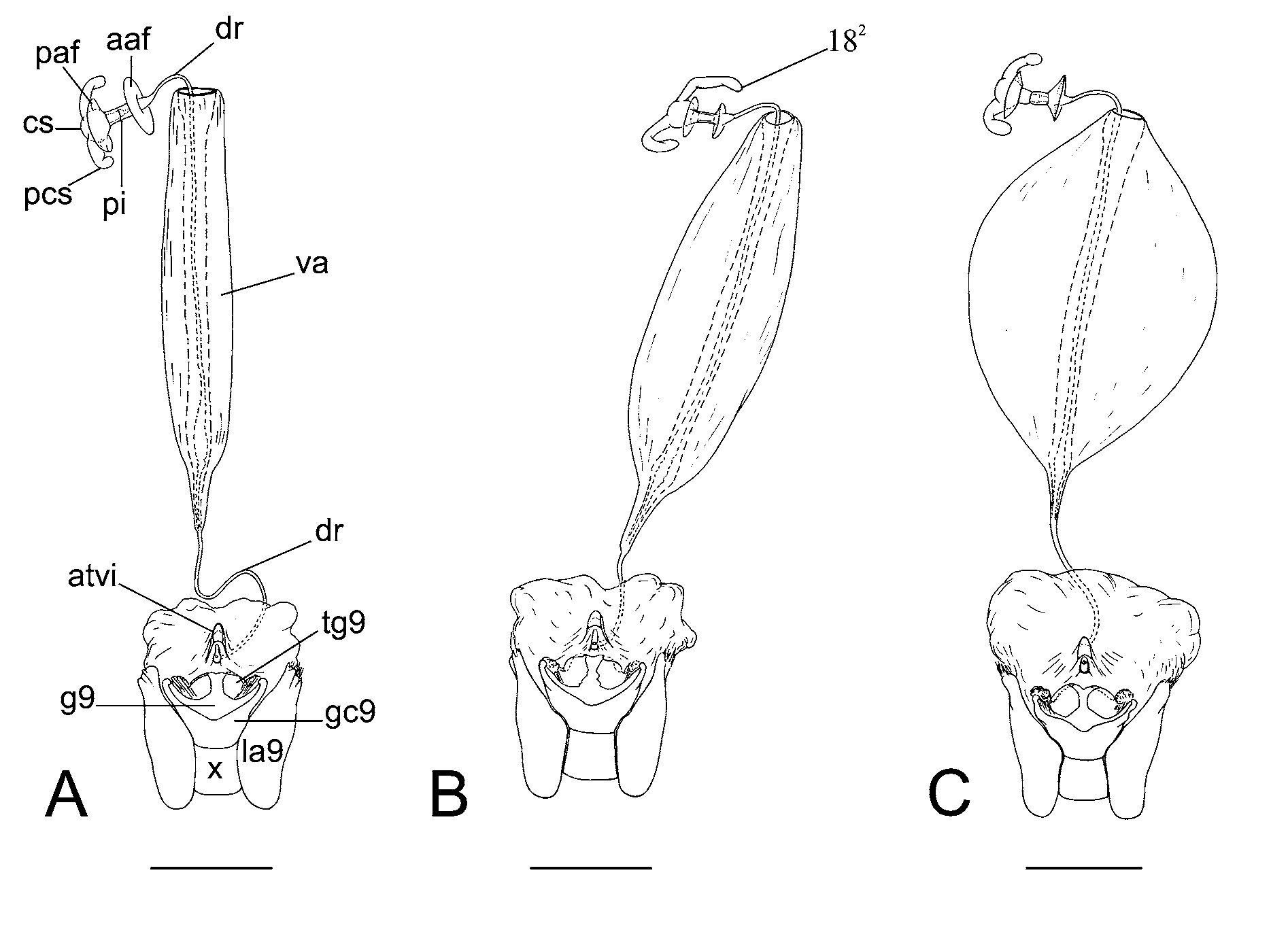

Character 18. Processes of capsula seminalis: (0) absent; (1) present, diameter reducing from base to acuminate apex; (2) present, sub cylindrical, rhomboid apex ( Fig. 17 View FIGURE 17 A–C View FIGURE 17 ). ci=100/ri= 100. Unambiguous.

Capsula seminalis with processes is a derived condition in Pentatomidae ( Grazia et al. 2008; Gapud, 1991), and are absent in Carpocoris purpureipennis . Campos & Grazia (2006) considered the diameter of the processes as an informative character. In the Nezara group, all species except Pseudoacrosternum cachani , have the processes of capsula seminalis, with acuminate or rhomboid apices ( Schwertner 2005). In Nezara , the processes are sub-cylindrical, well developed, and rhomboid at apex.

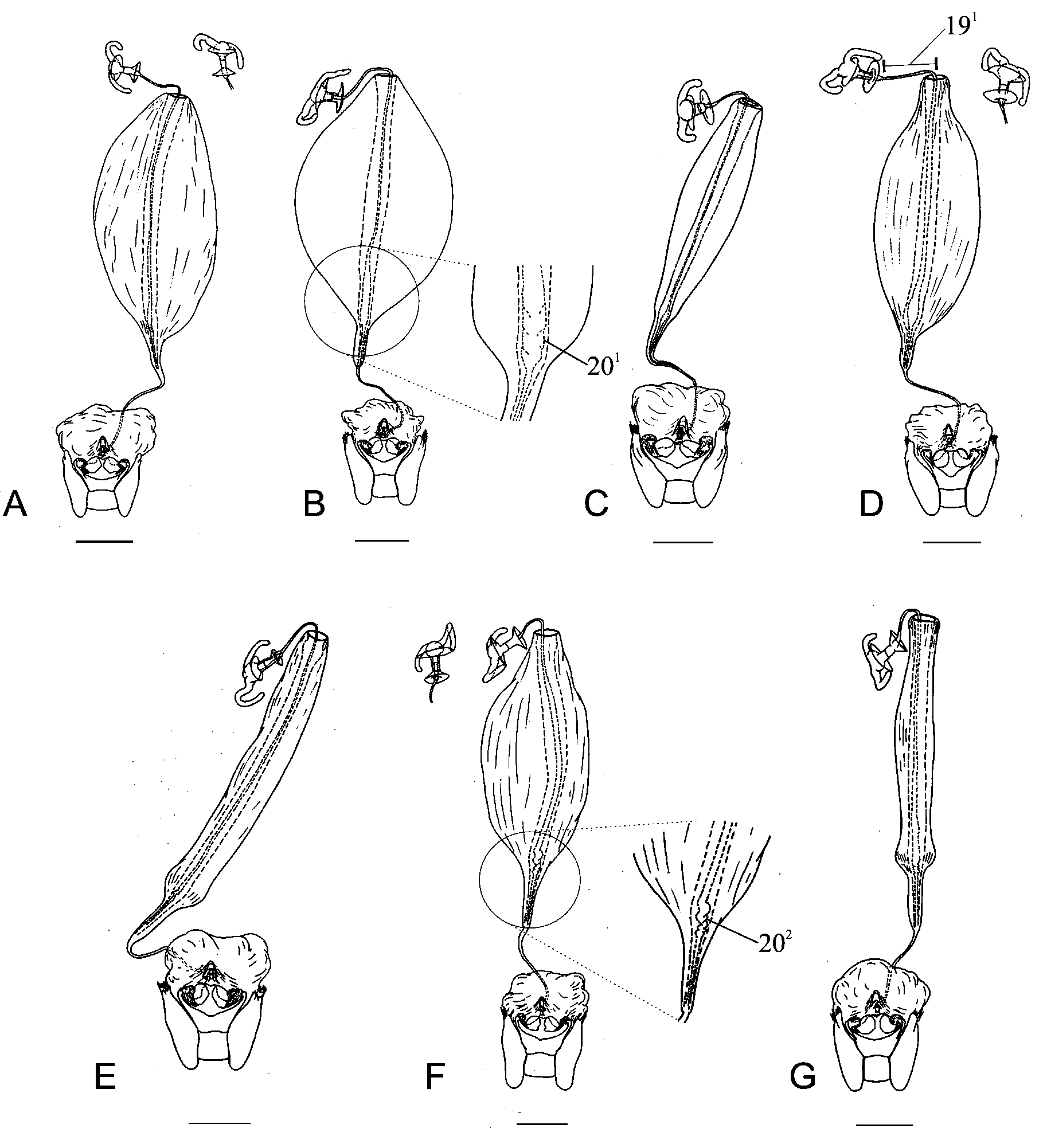

Character 19. Ductus receptaculi, distal area versus pars intermedialis: (0) ductus receptaculi less than three times the length of pars intermedialis ( Fig. 17 View FIGURE 17 C View FIGURE 17 ); (1) ductus receptaculi more than three times the length of pars intermedialis ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 D View FIGURE 18 ). ci=50/ri=50. Ambiguous

The ductus receptaculi, posterior to vesicular area, varies in length. Derived state found in some species of the ingroup has more than three times the length of pars intermedialis ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 D View FIGURE 18 ).

Character 20. Internal wall of ductus receptaculi: (0) without sinuosity; (1) with sinuosity, dilated ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 B View FIGURE 18 ); (2) with sinuosity, not dilated ( Fig. 18 View FIGURE 18 F View FIGURE 18 ). ci=66/ri=83. Ambiguous

The vesicular area results from the invagination of ductus receptaculi, which has three distinct walls ( Grazia et al. 2008). Campos & Grazia (2006) considered the diameter of the median and internal walls as informative characters. In Nezara , the internal wall may have a basal sinuosity.

Character 21. Gonapophyses 8, posterior margin: (0) without median longitudinal calloused band on posterior margin; (1) with median longitudinal calloused band on posterior margin. ri=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

Male genitalia

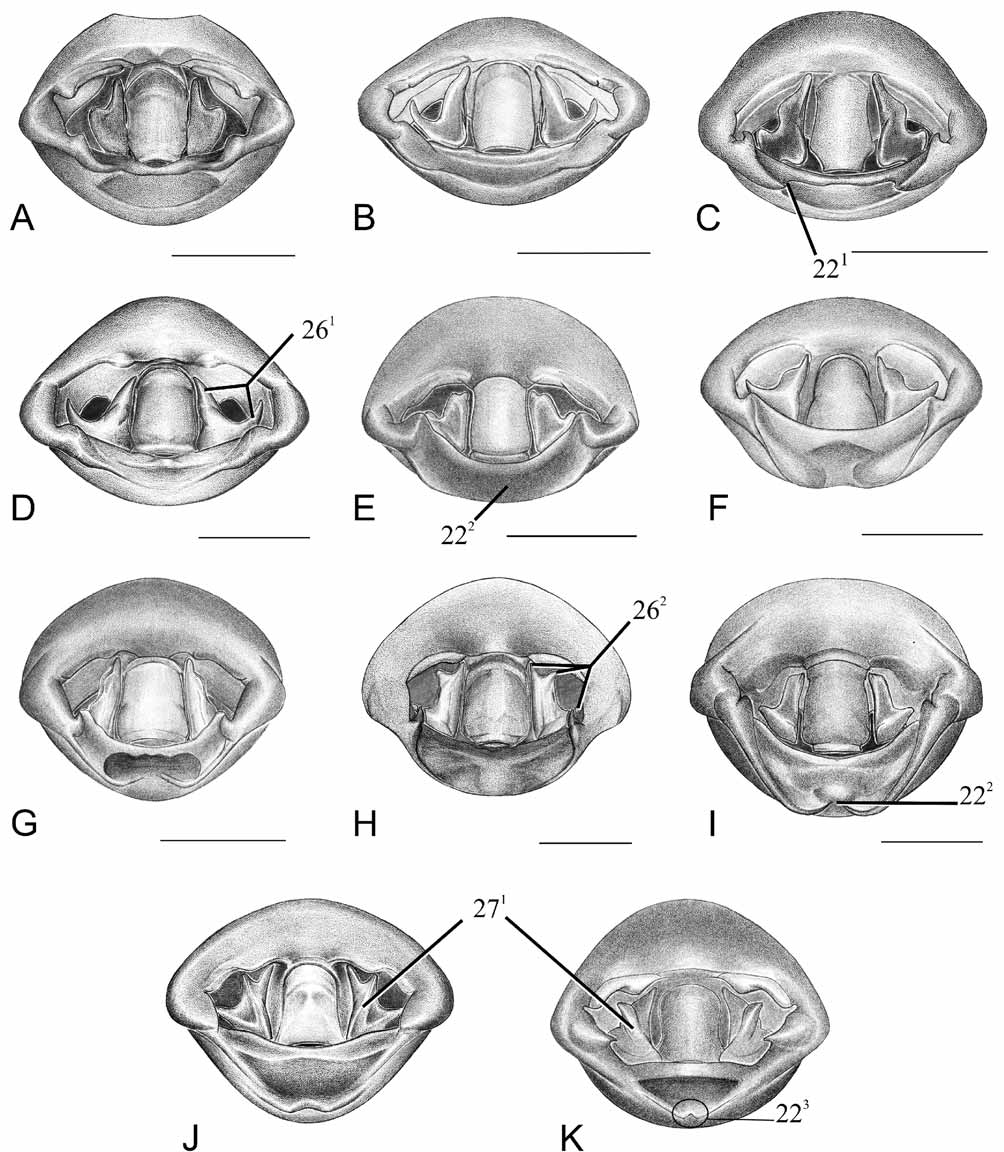

Character 22. Pygophore, ventral rim. (0) ventral rim not forming flaps; (1) flaps restricted to posterolateral angles, abruptly ending ( Fig. 8C View FIGURE 8 ); (2) flaps developed towards middle of ventral rim, continuous or not at mid line ( Fig. 8E–I View FIGURE 8 ). (3) flaps reduced, not continuous at mid line, with a bifid projection ( Fig. 8K View FIGURE 8 ). ci=100/ ri=100. Unambiguous.

Ventral rim and posterolateral angles of pygophore may have structures forming flaps visible in posterior view. These structures could be restricted to posterolateral angles ( Fig. 8C View FIGURE 8 ) or developed toward middle of ventral rim, continuous or not at mid line ( Fig. 8E–I View FIGURE 8 ). Sometimes the flaps are reduced, not continuous at mid line, and with a bifid projection ( Fig. 8K View FIGURE 8 ).

Character 23. Pygophore, superior process of dorsal rim: (0) posteriorly projected, apical region sclerotized; (1) forming a folded brim (semielyptical) ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N F View FIGURE 3 ); (2) forming a long brim developed towards ventral rim ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N G View FIGURE 3 ); (3) reduced or absent. ci=100/ri=100. Ambiguous.

Schaefer (1977) revised the terminology adopted by previous authors to the structures found in genital cup of Trichophora. However, till now there is not agreement in this terminology, probably because the lack of hypotheses of homology with well supported morphological and phylogenetic evidence. Within Pentatomidae , the use of distinct terminology has been very damaging to the interpretation and use of these characters in comparative studies ( Schwertner 2005). Here, we assume the correspondence of this character with the following: “superior lateral process” ( Sharp 1890), “genital plates” ( Baker 1931), “processus superieur” ( Dupuis 1970) and “genital cup processes” ( Barcellos & Grazia 2003).

Character 24. Pygophore, infolding of dorsal rim: (0) absent; (1) hairy region forming a simple band ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N F View FIGURE 3 ); (2) hairy region divided into two lobes of similar size ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N G View FIGURE 3 ); (3) hairy region divided into two lobes, one of them extending towards the internal wall of genital cup ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N H View FIGURE 3 ). ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

Barcellos & Grazia (2003) and Fortes & Grazia (2005) used characters related to expansions of the infolding of dorsal rim of the pygophore. Here, the outgroup was codified as lacking this structure because it does not have a hairy region at the infolding of the dorsal rim. However, Carpocoris purpureipennis has three other structures on the genital cup ( Tamanini 1958), that could be related to this character, as well as to character 23, beside the distinct morphology of them. In Aethemenes chloris , a line of hairs on dorsal rim, not forming a hairy band, is present, and was codified as absent for this character. Schwertner (2005) named this structure as marginal process of the infolding of dorsal rim, and the state calloused was found as a synapomorphy for Nezara . These calloused marginal processes could present the hairy region more or less expanded: in Nezara robusta and N. immaculata this region is expanded towards the ventral rim surpassing the imaginary line between the posterolateral angles of pygophore ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N H View FIGURE 3 ); in N. orbiculata the hairy region almost reaches the internal wall of genital cup. The illustrations show the limits of the hairy regions (the hairs were ommited).

Character 25. Pygophore, cup like sclerite: (0) low, not elevated, not occupying one third of the diameter of pygophore; (1) well sclerotized and elevated, occupying one third the diameter of pygophore ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N B View FIGURE 3 , 4A View FIGURE 4 ). ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

A cup like sclerite, well sclerotized, occupying one third the diameter of pygophore, with anterior and lateral limits elevated from the internal wall of pygophore ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4. N A View FIGURE 4 ) is exclusively found in all species of Nezara . In one of the outgroup species, Aethemenes chloris , has a cup like sclerite similar in diameter to Nezara but the anterior limit is fused to the pygophore wall. In Pseudoacrosternum cachani , the cup like sclerite is less elevated not occupying one third of the diameter of pygophore.

Character 26. Parameres lobes: (0) absent; (1) bilobate ( Fig. 8D View FIGURE 8 ); (2) trilobate ( Fig. 8H View FIGURE 8 ). ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

Morphology of parameres is often used in taxonomy and cladistics of Pentatomidae (i.e. McDonald 1966, Linnavouri 1972). Freeman (1940) characterized Nezara species based on the morphology of parameres in posterior view, emphasizing that in this position it was not necessary to remove the genitalia to identify the species. Barcellos & Grazia (2003) and Fortes & Grazia (2005) found strong synapomorphies in the morphology of parameres to define monophyletic groups of species. Schwertner (2005) used four distinct characters based on parameres morphology, including the development of the apical part in two or more lobes. Species of Nezara may have two or three lobes, often perpendicularly positioned in relation to the sagittal plane of the body, and easily visible in posterior view. Nezara mendax and N. soror have the apical part of the parameres developed into three lobes, one of which in sagittal plane, appears bilobate when observed in posterior view.

Character 27. Paramere, carina on median lobe: (0) absent; (1) present ( Fig. 8J–K View FIGURE 8 ). ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

If parameres are trilobate, then a carina may be present on the median lobe, posteriorly projected. This character was codified as not observed in the species having parameres without lobes or bilobate.

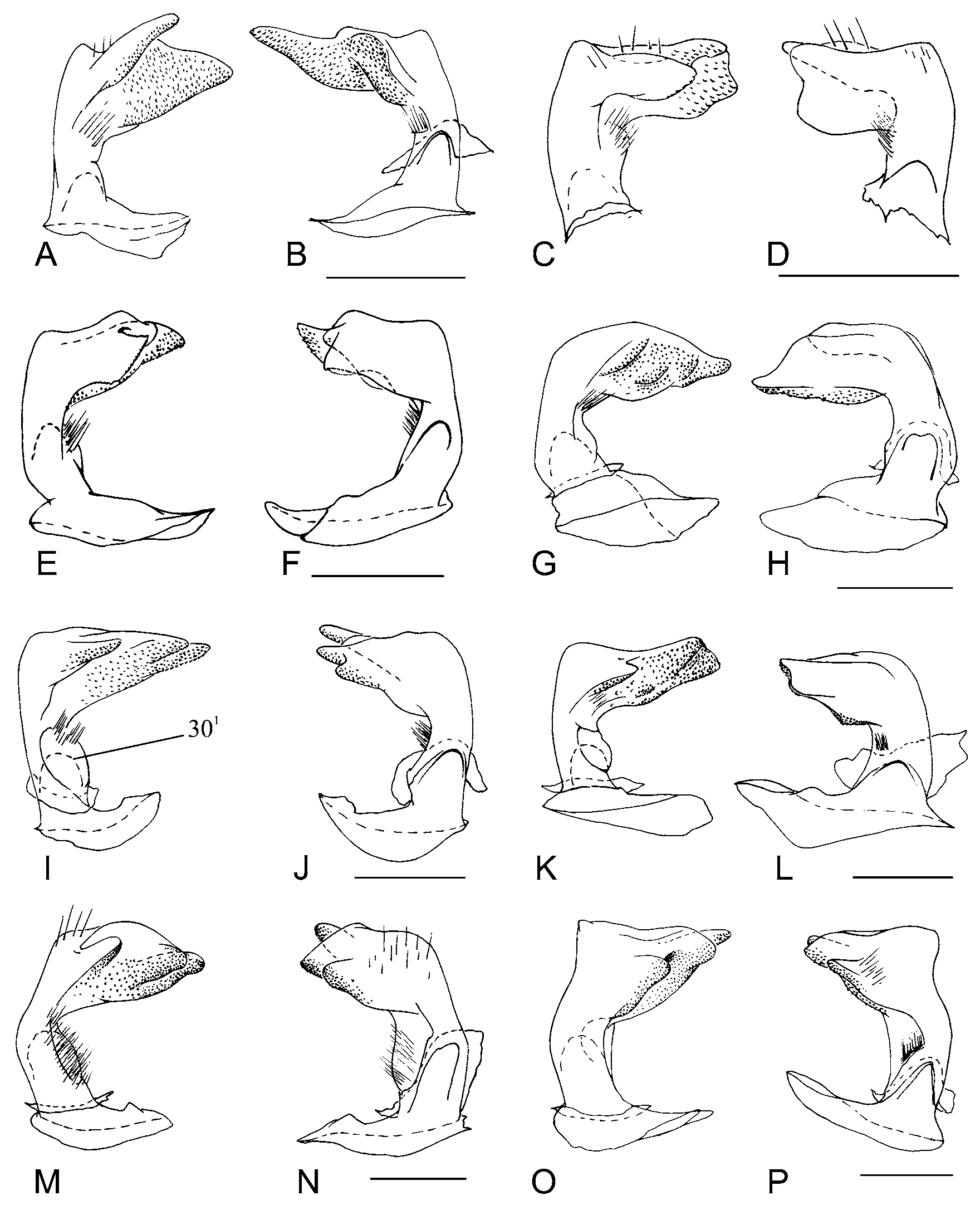

Character 28. Parameres, median bristles: (0) absent; (1) present. ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

Parameres with median bristles are often present in the Pentatomidae (e.g. McDonald 1966; Gross 1976; Linnavouri 1982). In Carpocoris purpureipennis , bristles are absent. In Nezara , the bristles are placed midway between the apical and basal parts of the paramere, on the internal surface. They can sometimes be reduced in number, as in N. viridula ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 C–E View FIGURE 12 ) and N. similis ( Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 A–B View FIGURE 11 ), or may be in higher density, occupying almost the entire lateral surface of the paramere, as in N. immaculata ( Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 M–N View FIGURE 11 ).

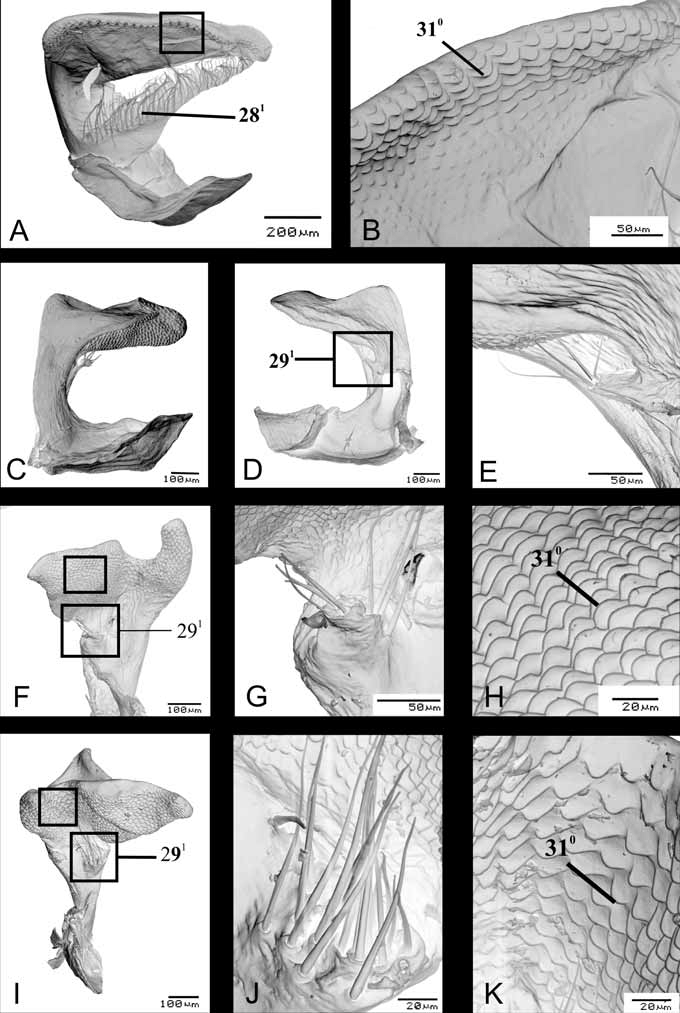

Character 29. Parameres, attachment of median bristles: (0) attached directly on paramere wall ( Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 B, E View FIGURE 13 ); (1) attached on a short, digitiform process which is itself attached to the lateral surface of the paramere ( Figs. 10 View FIGURE 10 C–H View FIGURE 10 , 12C, D, F, I View FIGURE 12 ). ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

The median bristles may be attached directly to the wall of the paramere ( Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 A, I, N View FIGURE 11 ; Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 B, E, H, K View FIGURE 13 ), or in a short digitiform process ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 E, G, J View FIGURE 12 ). Although Pseudoacrosternum cachani has a long process with bristles attached along its entire length ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 AB), the morphology of the process is distinct, and this character was codified as innapplicable. Freeman (1940) described a digitiform process in N. antennata and N. viridula , state also shared by N. yunnana . Santoro (1954) illustrated this character in N. viridula , but McDonald (1966) omitted the process in his illustration. Bao-ying et al. (2000) studied the morphology of the genital microstructures, using SEM, in distinct population of N. viridula from Australia and Slovenia, showing this character in detail.

Character 30. Paramere, elyptical area. (0) absent; (1) present. ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous. Some species of Nezara have the bristles attached to an elyptical area at middle of paramere, diagnonally positioned in relation to longitudinal plane ( Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 I View FIGURE 11 ; Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 E View FIGURE 13 ).

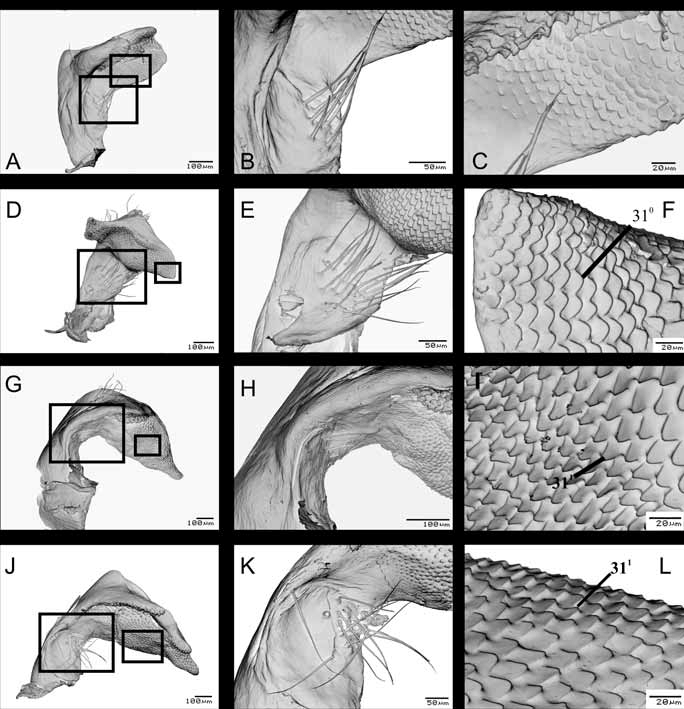

Character 31. Parameres, tegumentar microsculptures: (0) crenulate ( Fig. 12 View FIGURE 12 B,H, K View FIGURE 12 );(1) serrulate ( Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 I, L View FIGURE 13 ). ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

Anterior surface of apical part of paramere, in S.E.M, show two distinct tegumentar microsculptures: crenulate and serrulate. This character was illustrated by Freeman (1940) and McDonald (1966) for N. viridula , using light microscopy, but the form of these structures was difficult to observe. The character is broadly distributed among Heteroptera , being present in several species of Pentatomidae ( McDonald 1966) , Scutelleridae ( Cassis & Vanags 2006) , and Corixidae ( Tinerella 2006) .

Character 32. Phallotheca, median projection of ventral margin ( Fig. 15 View FIGURE 15 F View FIGURE 15 ): (0) absent; (1) present. ci=100/ ri=100. Unambiguous.

Character 33. Phallus, secondary gonopore process: (0) Secondary gonopore process larger than gonopore diameter ( Fig. 14 View FIGURE 14 A–B View FIGURE 14 ); (1) Secondary gonopore process less than one third gonopore diameter ( Fig. 4 View FIGURE 4. N B View FIGURE 4 ). ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

Character 34. Phallus, processus capitati: (0) equal or slightly larger than dorsal connective diameter ( Fig. 14 View FIGURE 14 A–C View FIGURE 14 ); (1) at least three times larger than dorsal connective diameter ( Fig. 14 View FIGURE 14 D View FIGURE 14 ). ci=100/ri=100. Unambiguous.

In Nezara , the processus capitati is more robust than in other taxa of Nezara group ( Schwertner 2005). Here, we compare the processus capitati diameter in relation to the diameter of dorsal connective.

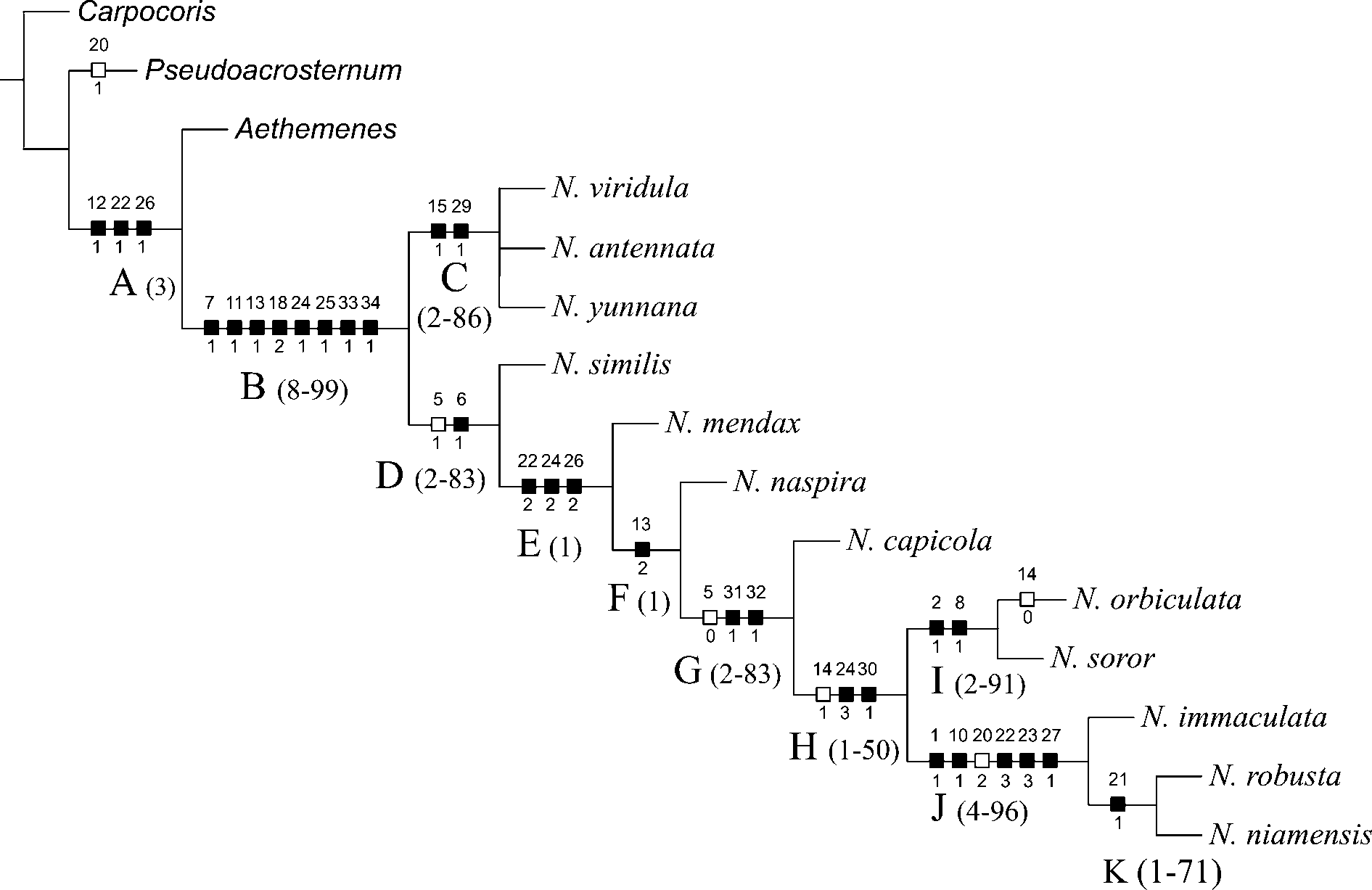

Analysis

The analysis of parsimony resulted in one cladogram with 60 steps, consistence index (CI) of 0.81 and retention index (RI) of 0.89 ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ).

Monophyly of the genus Nezara (Clade B) was corroborated by eight synapomorphies, one of general morphology, three of female genitalia and four of male genitalia ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ): median tubercle on urosternite III present (7 1); posterior margin of urosternite VII strongly arcuate ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 B View FIGURE 16 ), well elevated in relation to the placement of genital plates (11 1); basal half of laterotergites 9 concave (13 1); processes of capsula seminalis subcylindrical, rhomboid at apex (18 2); hairy region of the infolding of ventral rim of pygophore forming a simple band (24 1); cup like sclerite well sclerotized and elevated, occupying one third the diameter of pygophore, the anterior limit not fused to the infolding of dorsal rim (25 1); secondary gonopore process of phallus less than one third the gonopore diameter (33 1), and diameter of processus capitati at least three times larger than dorsal connective diameter (34 1). Six synapomorphies of eight are exclusive to the genus Nezara among Pentatominae , and increase the number of diagonostic characters of the genus ( Schwertner 2005)

A basal dichotomy ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ) splits the two oriental species and N. viridula (Clade C), from the afrotropical species (Clade D). Clade C include N. viridula , N. antennata and N. yunnana , which share two synapomorphies: concave areas (1+1) on gonocoxites 9 present (15 1, Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 A–C View FIGURE 16 ), and median bristles attached in a short digitiform process bent to lateral surface of paramere (29 1 Figs. 10 View FIGURE 10 C–H View FIGURE 10 , 12C, D, F, I View FIGURE 12 ). A hypothesis of relationship among species of clade C, based on the characters analysed here, was not obtained. Kon et al. (1988) and Kon et al. (1993) studied interespecific mating behaviour in N. antennata and N. viridula , evidencing the proximity of these species. However, for N. yunnana these data are still unknown, which make unapplicable the use of that character in a cladistic analysis.

Clade D, including the remaining species of Nezara , is supported by the green hemelytral veins present (6 1), a derived state found in all taxa of this clade, and by the homoplasious character metapleural evaporative area occupying less than half of the metapleura (5 1).

Clade E shares three derived states: ventral rim of pygophore with brims developed towards middle of ventral rim, continuous or not at mid line (22 2, Fig. 8E–I View FIGURE 8 ) [the state changed on clade J where the brims are reduced, not continuous at mid line, with a bifid projection (22 3, Fig. 8J–K View FIGURE 8 )]; infolding of dorsal rim of pygophore with hairy region divided in two lobes of similar size (24 2, Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N G View FIGURE 3 ) [the state changed on clade H where the hairy region is divided in two lobes, one of them extending towards the internal wall of genital cup (24 3, Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N H View FIGURE 3 )]; paramere trilobate was the only exclusive synapomorphy shared by all taxa of this clade (26 2, Fig. 8E–K View FIGURE 8 ), what could explain the weak Bremer suport of clade E.

Clades G and H are defined by two synapomorphies each, on characters of male genitalia. Clade G was supported by parameres with serrulate tegumentar microsculptures (31 1, Fig. 13 View FIGURE 13 I,L View FIGURE 13 ), and median projection of ventral margin of phallotheca present (32 1, Fig.15 View FIGURE 15 C,E,F,I View FIGURE 15 ). Clade H was supported by the infolding of the dorsal rim of pygophore with a hairy region divided into two lobes, one of them extending towards the internal wall of genital cup (24 3, Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N H View FIGURE 3 ), and paramere with elyptical area (30 1, Fig. 11 View FIGURE 11 I View FIGURE 11 ).

Clade I, corresponding to N. orbiculata + N. soror , shares two derived states of general morphology characters: basal third of corium convex, surpassing an imaginary line tangential to the humeral angles (2 1, Fig. 3A View FIGURE 3 2 View FIGURE 2 ); connexival segments IV to VII exposed in dorsal view (8 1, Fig. 3A View FIGURE 3 2 View FIGURE 2 ).

Clade J, including N. immaculata , sister-group of N. robusta + N. niamensis shares five synapomorphies, two of general morphology and three of male genitalia: lines of punctures on pronotum present (1 1); margins of body with red band; ventral rim of pygophore with brims reduced, not continuous at mid line, with a bifid projection (22 3); superior process of dorsal rim of pygophore reduced or absent (23 3); paramere with median lobe carina (27 1). Support of clade J was given by characters of general morphology (1 1, 10 1) and the derived state of the character 20 2 (internal wall of ductus receptaculi with sinuosity, not dilated), considering that the males of N. niamensis were not available in this study.

Clade K formed by N. robusta + N. niamensis is supported by gonapophyses 8 whith median longitudinal calloused band on posterior margin (21 1).

Nine characters and 12 states showed ambiguous reconstruction, five from general morphology (3 1, 3 2, 3 3, 4 1, 9 2), five from female genitalia (14 1, 16 2, 17 1, 19 1, 20 1), and two from male genitalia (23 1, 23 2). Female characters 16 2, 17 1 and 20 1 had more than one explanation, due to missing data (females of N. similis and N. mendax were not dissected). Character internal wall of ductus receptaculi has the state 20 2 (with sinuosity, not dilated) as a synapomorphy to clade J, however the state 20 1 is ambiguous. Both multistates characters 14 and 23 when optimized with ACCTRAN are synapomorphies to Nezara (Clade B, Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ); using DELTRAN option, derived states appear as synapomorphies to clades C (oriental species) and D (afrotropical species). Therefore, characters 14 and 23 represent possible synapomorphies to clades C and D, respectively.

The morphology of genitalia offers valuable exclusively derived characters in generic or suprageneric cladistics studies of Pentatomidae ( Grazia 1997; Barcellos & Grazia 2003; Fortes & Grazia 2005; Schwertner 2005), representing half or more of the synapomorphies found, with the prevailing of male characters. In taxonomic studies, the morphology of genitalia is extensively used due to the variability of the structures. Male structures are more susceptible to female selective pressure, being more divergent in closely related species than non sexual characters ( Eberhard 1985; Eberhard 2004).

In Nezara , morphological characters of genitalia, especially on males, showed the best congruence and phylogenetical signal. Female characters were important to define basal synapomorphies of Nezara , being present on clade B ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 ), and indicating to be more conservative structures of the analysed taxa. Characters of the parameres, visualized by S.E.M., were important to establish relationship among species.

Biogeography

Biogeographical scenarios concerning the evolution of Nezara were based in the areas of occurrence of each species and the phylogenetic relationships among them ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6 ). The limits of the areas of occurrence of each species were defined as the peripherical localities in the map presented in Fig 6A View FIGURE 6 . In order to avoid relationship inferences among taxa (and its areas) with low support, branches with Bremer support less than 2 steps were collapsed.

Dispersal and vicariance are often considered competing hypotheses in historical biogeography. Disjunct distribution patterns can be explained either by fragmentation of widespread ancestors due to vicariant (isolating) events or by dispersal across a preexisting barrier ( Sanmartín & Ronquist 2004). Today, historical biogeography considers dispersal, vicariance, and extinction as processes equally responsible to affect distribution ( Posadas et al. 2006). Considering the difficulties to test dispersal and extinction hypotheses ( Morrone & Crisci 1995), they were assumed as secondary events to understand the present-day distributional patterns of Nezara species.

It has been accepted that taxa with similar distributional patterns, and congruent relationship among areas, share a common history as a result of geographical isolation events ( Nelson & Platinick 1981). However, the biogeographical history of many Gondwanan groups is not a simple story of vicariance, as trans-oceanic dispersal has often played an important role in achieving present-day distributions ( Briggs 2003; Sanmartín & Ronquist 2004; Fuller et al. 2005; Boyer & Giribet 2007; Volker & Outlaw 2008). The inclusion of a temporal perspective in the comparison of taxa distribution patterns, through the definition of Cenocrons, sets of taxa that share the same biogeographic history, constituting identifiable subsets within a biotic component by their common biotic origin and evolutionary history ( Morrone 2009), is an important process in the search for biogeographic patterns. Donoghue & More (2003) emphasized the necessity to consider divergence times of lineages in biogegraphical studies in order to avoid inference of patterns produced by pseudo-congruence.

With the exception of N. viridula , localities of most of the species of Nezara are associated mainly with tropical or subtropical rain forests ( Fig. 6A View FIGURE 6 ). We assume that the limits of the distribution of the genus have been associated with the evolution of the tropical rain forests, agreeing to the environmental scenario described by Morley (2003) to megathermal angiosperms.

Nezara first cladogenetic event was the basal split of the clade including N. viridula , N. antennata and N. yunnana ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 , Clade C) from the African species (clade D). A possible geological vicariant hypothesis associated to this event is the West Gondwana break during mid Jurassic (~170 Ma) ( Lawver et al. 2003), resulting in the drift of the India-Madagascar plate from the African plate. However, it would imply that the basal split of Nezara would have happened 20 Ma before Pentatomoidea oldest fossil record ( Yao et al. 2007). Grimaldi & Engel (2005), based in most ancient fossil records, estimated that the Pentatomomorphan basal families probably have its origin in late Jurassic (161–145 Ma), and that the Pentatomoidean most basal families did not appear before Cretaceous (145 Ma). According to Grazia et al. (2008), the family Pentatomidae is among the most derived clades within Pentatomoidea .

Oldest known fossils represent minimun ages estimates ( Heads, 2005). Althought the minimum fossil ages of Pentatomoidea may not represent absolute estimates related to the origin of the taxon, to suppose that Nezara ancestral have had a wide distribution in West Gondwana (<160 Ma) is a low supported hypothesis. According to Briggs (2003), based on estratigraphical, paleomagnetical and paleontological data, India and Africa were more related biogeographically to each other than previous hypothesized in the literature. A great amount of faunal exchanges could have occurred among India, Africa and Madagascar while the Indian plate drifted towards Eurasia. This hypothesis fits with the Nezara ancestral basal split being associated with a dispersal event favoured by the drop in sea level in the late Cretaceous (Hallan, 1992 apud Briggs 2003), exposing continental shelves and decreasing distances among landmasses.

Among the African species of Nezara ( Fig. 5 View FIGURE 5 , Clade D) most appear restricted mainly to tropical rain forests and related ecossystems (i.e. tropical woodland/grassland savanna). Two species ( N. mendax and N. immaculata ) are associated to arid enviroments of the east Africa, while N. capicola is associated to the sclerophyllous forest of the Western Cape Province, and to the South Africa highlands. The majority of the species distribution areas are based on few records, reflecting the inadequate data collection and making difficult the interpretation of their current distribution. However, the diversification of the Afrotropical fauna and flora has a complex history related to the expansion and contraction of the tropical forests ( Morley 2003; Plana 2004; Rønsted et al. 2007), which certainly influenced the evolution and current distributions of Nezara . Increasing of rain forests areas in African southeast along Eocene (54 Ma) through Oligocene (33 Ma) ( Morley 2003) could have favoured the distribution of Nezara to south and southeastern parts of Africa. The inclusion of N. soror , an eastern Madagascar (rain forests) endemic species ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6. A B View FIGURE 6 ), in the African clade strongly supports the expansion in the distribution after gondwanic breakup, including a dispersal event to Madagascar. Fuller et al. (2005) proposed an afrotropical origin to Braunsapis ( Hymenoptera , Apidae ), with at least two dispersal events to Madagascar, with estimated times of 13 Ma and 2–3 Ma, rejecting vicariant hypothesis to explain the distributional pattern, considering that the genus would be more ancient than the tribe Allodapini , to which it belongs.

Biondi & D’Alessandro (2006), using distribution areas of 123 species of the beetle genus Chaetocnema Stephens , identified 13 chorotypes in the Afrotropical region, five of them also fit to the species of Nezara : N. naspira is related to Afro-Intertropical chorotype; N. orbiculata , N. niamensis , and N. similis are related to the Afro-Equatorial chorotype; N. immaculata and N. mendax are restricted to the Northern-Eastern Afrotropical chorotype; N. robusta is resctricted to the south of the Central Afrotropical chorotype; N. frontalis is resctricted to the Southern African chorotype, and N. soror is restricted to the Malagasy chorotype. With the exception of the Northern-Eastern Afrotropical chorotype, the chorotypes corresponds roughly to the areas of endemism located by Linder (2001) and Biondi & D’Alessandro (2006). Linder (2001) found a strong congruence between areas of endemism and areas of species richness for plants in the sub-Saharan Africa, the latter pattern being strongly influenced by historical variation in the climate, the former being linked to the current climate conditions ( Linder 2001, Plana 2004).

The clade including N. viridula , N. antennata , and N. yunnana occur mainly in the Oriental region, associated to tropical or subtropical rain forest. Nezara yunnana occurs in the north of India, and farther southern in China (the type locality in Duanli, Yunnan, China). Nezara antennata has a more widespread distribution. Based on label records of the studied specimens, N. antennata occurs in southern China, South Korea and Japan, while in the literature this species is also recorded to India, Philippines, and Sri Lanka ( Rider 2006).

Nezara viridula is cosmopolitan occuring in all biogeographical regions, except Antarctica ( DeWitt & Godfrey 1972; Panizzi et al. 2000). The species was described from India ( Linnaeus 1758). The first record in the Neotropical region was made by Fabricius (1798) to the West Indies, and since then several other records to the neotropics included Central and South America (i.e. Amyot & Serville 1845; Pennington 1919). It was cited first in Japan in 1874–1879 ( Yukawa et al. 2007), and Clark (1992) mentioned that the first record to Australia was made by Froggat in 1916. The distributional area of N. viridula is still expanding ( Todd 1989; Aldrich 1990; Clarke 1992) as a result of commercial and agricultural expansion ( Jones 1988; Todd 1989; Meglic et al. 2001). More recently, the expansion in the distribution of this species was related to the global warming ( Musolin and Numata 2003; Musolin 2007; Yukawa et al. 2007).

Based in the analysis of the distributional areas and frequencies of the polymorphic types, Yukawa & Kiritani (1965) proposed the origin of N. viridula for the southwest Asia. According to Jones (1988), these authors had only considered polymorphic types of restricted areas. Jones (1988) based on the distribution of Nezara species, color polymorphs and egg parasitoid complexes, considered the origin of N. viridula as Ethiopic. Hokkanen (1986) reached the same conclusions based on color polymorphs, parasites and ecological characteristics. More recently, Kavar et al. (2006) sequenced 16S and 28S rDNA, cytochrome b and cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene fragments and random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) from geographically separated sampling locations ( Slovenia, France, Greece, Italy, Wood, Japan, Guadeloupe, Galapagos, California, Brazil and Botswana). Based on these results, the authors supported an African (Botswanian specimen) origin of N. viridula , followed by dispersal to Asia and, more recently, by expansion to Europe and America. They also suggested that the African and non-African gene pools have been separated for 3.7–4 Ma, through the estimative of the divergence time using the standard insect molecular clock of 2.3% pairwise divergence per million years.

Based on the resulted cladogram ( Fig. 6 View FIGURE 6. A B View FIGURE 6 ), two possible explanations for the original area of N. viridula could be formulated: 1) the species had its origin in the Oriental area, from the ancestral of the Oriental clade ( N. viridula , N. antennata and N. yunnana ), with a posterior expansion from Asia to African continent, or 2) a basal lineage of the Oriental clade with northeastern African distribution that dispersed to Indian plate in Eocene, originating the ancestral of N. yunnana and N. antennata ; in this case, the remnant African population gave origin to N. viridula , which subsequently expanded to Asia. However, just a more comprehensive study including different data sources (i.e. molecular, pheromones, reproduction, sound comunication, etc…) of all species included in the Oriental clade, and at least some of the African species, will be crucial to establish the relationships of the clade C and the recognition of a possible ancestral area for N. viridula .

Taxonomy

Nezara Amyot & Serville, 1843 View in CoL View at ENA

Nezara Amyot & Serville, 1843 View in CoL : xxvi, 143–144 (descr.); Fieber, 1861: 329 (descr.); Stål, 1865: 192 (descr.); 1867: 530 (key); 1872: 40 (descr.); 1876: 63, 91 (key, descr.); Mulsant & Rey, 1866: 288 (descr.); Puton, 1881: 52 (key); Lethierry & Severin, 1893: 164 (cat.); Distant, 1902: 219 (descr., type species des.); Kirkaldy, 1909: 115 (cat.); Bergroth, 1914: 24 (diagnosis); Freeman, 1940: 354 (review); Azim & Shafee, 1978: 507 –511 (key); Cassis & Gross, 2002: 519 (cat.); Rider, 2006: 328 (cat.).

Type species: Cimex smaragdulus Fabricius, 1775 (= Cimex viridulus Linnaeus, 1758 ).

Diagnosis. Median tubercle on urosternite III present and sacarcely projected in most of the species, apex rounded or conical, surpassing metacoxae in N. orbiculata . Green macula juxtaposed to spiracles with less or more than two times the spiracles diameter. Posterior margin of urosternite VII excavate in “U” in females ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 b View FIGURE 16 ), well elevated in relation to the placement of genital plates; basal half of laterotergites 9 entirely concave or concave at lateral margin and convex at middle margin, sometimes forming a callus; processes of capsula seminalis subcylindrical, rhomboid at apex. Male: hairy region of the infolding of ventral rim of pygophore forming a simple band; cup like sclerite well sclerotized and elevated, occupying one third the diameter of pygophore, the anterior limit not fused to the infolding of dorsal rim three times larger than dorsal connective diameter. infolding of dorsal rim of pygophore with a hairy region in a band forming two lobes similar in size or one of the lobes projected towards internal wall of genital capsule. Superior process of dorsal rim forming a folded brim or a long brim developed towards ventral rim. Phallus: processus capitati diameter at least three times larger than dorsal connective diameter, and secondary gonopore process of phallus less than one third the gonopore diameter.

Comments. Diagnosis of Nezara based on unique derived characters was established only recently ( Schwertner 2005). Amyot & Serville (1843) proposed Nezara among the taxa with an abdominal tubercle or spine present (the ‘Raphigastrides’ group), and was followed by subsequent authors (i.e Stål 1865; 1872; 1876; Atkinson 1888; Distant 1902). In his catalogue, Kirkaldy (1909) listed six subgenera in Nezara . Bergroth (1914) recognized each of the subgenera proposed by Kirkaldy (1909) as valid genera. Also Bergroth (1914) included in Nezara only those species with ostiolar peritreme short, not reaching the anterior margin of metapleura (= division a of Stål, 1876, see Introduction). Freeman (1940) strengthen the number of characters to separate Nezara from the allied genera, including the position of the pygophore (‘clearly visible in ventral view’) and the shape of the parameres (‘broad and apically turnwards, the free ends of each being produced into lobes two or three in numbers’). However, Orian (1965) discussed the characters used by Bergroth (1914) and Freeman (1940), the only one useful to diagnose the genus Nezara was the shape of the paramere.

More recently, in a cladistic analysis including several genera of stink bugs ( Schwertner 2005), the monophyletic condition of Nezara was supported, and unique derived characters for the genus were defined: concavity of the posterior margin of VII urosternite in “U”; surface of the basal half of laterotergites 9 strongly concave, and diameter of processus capitati larger than length of the dorsal connective. One homoplastic character, the green maculae juxtaposed to the spiracle, was found in all species of Nezara , and also in Pseudoacrosternum cachani Day ( Schwertner 2005) . The shape of the paramere, character used by Freeman (1940) to separate species of Nezara from allied genera, was a synapomorphy to the clade including Aethemenes , Nezara and Pseudoacrosternum ( Schwertner 2005) .

Key to the species of Nezara View in CoL (male and female):

1. Scent glands with spout of peritreme never elongate, ear-like ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N E View FIGURE 3 )...................................................................... 2

1’. Scend glands with spout of peritreme elongate ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N D View FIGURE 3 ). ........................................................................................... 3

2. Peritreme short, inconspicuous; ostiolar orifice round, completely visible in lateral view of metapleura; evaporative area of scent gland occupying less than half of metapleura ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N E View FIGURE 3 ) .......................................................................... 5

2’. Peritreme conspicuous; ostiolar orifice ellyptical, completely visible in ventral view of metapleura; evaporative area of scent gland large, occupying more than half of metapleura ( Fig. 3 View FIGURE 3. A 1 – 2. N D View FIGURE 3 ) ..................................................................... 6

3. Basal third of corium straight, not surpassing an imaginary line tangencial to humeral angles .................. N. capicola

3’. Basal third of corium convex, surpassing an imaginary line tangencial to humeral angles ( Fig. 3A View FIGURE 3 ) ......................... 4

4. Black macula on urosternites larger than abdominal spiracles; medial spine of third abdominal segment very short, not reaching hind coxae. ................................................................................................................................... N. soror

4’. Black macula on urosternites shorter than abdominal spiracles; medial spine of third abdominal segment very long, reaching anterior margin of median coxae ( Fig. 3A View FIGURE 3 )................................................................................. N. orbiculata

5. Anterior margins of pronotum straight; humeral angles in right angles ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 D View FIGURE 1 ) ......................................... N. similis

5’. Anterior margins of pronotum slightly convex; humeral angles rounded ( Fig. 1 View FIGURE 1 E View FIGURE 1 )...................................... N. mendax

6. Pronotum tranversely ridged, usually more ligther in color than grooves ( Fig. 2 View FIGURE 2 D–F View FIGURE 2 ); black macula on scutellum basal angles absent; black macula on urosternites shorter than abdominal spiracles or absent................................... 7

6’. Pronotum not ridged; black macula on scutellum basal angles present; black macula on urosternites equal or larger than abdominal spiracles............................................................................................................................................... 9

7. Black macula on urosternites present .......................................................................................................................... 8

7’. Black macula on urosternites absent....................................................................................................... N. immaculata

8. Anterior margins of pronotum convex; ridges and grooves of pronotum with the same colour .................. N. robusta

8’. Anterior margins of pronotum straight; ridges and grooves of pronotum with alternated light and dark colour .......... ................................................................................................................................................................... N. niamensis

9. Evaporative area of scent glands occupying less than half of metapleura; gonocoxites 8 with longitudinal groove reaching VII abdominal segment ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 F View FIGURE 16 ), base of laterotergites 9 with callus; male with parameres trilobate ( Fig. 8F View FIGURE 8 ) .................................................................................................................................................................. N. naspira

9’. Evaporative area of scent glands occupying at least half of metapleura; gonocoxites 8 with longitudinal groove inconspicuous, never reaching VII abdominal segment, base of laterotergites 9 concave ( Fig. 16 View FIGURE 16 A-C); male with parameres bilobate ( Fig. 8A–C View FIGURE 8 ).................................................................................................................................. 10

10. Connexival sutures with black or darkened maculae at middle; black macula on apex of antennal segments III and IV; lobes of parameres equal in length, the lateral thinner than the meddian ( Fig. 8B View FIGURE 8 ); digitiform processes of capsula seminalis distinct in length, one surpassing anterior annular flange ( Fig. 17 View FIGURE 17 B View FIGURE 17 )........................................ N. antennata

10’. Connexival sutures without black maculae; reddish or ferrugineous, never black, macula on apex of antennal segments III and IV; median lobe of parameres longer than the lateral one ( Fig. 8A,C View FIGURE 8 ); digitiform processes of capsula seminalis subequal in length, never surpassing anterior annular flange ..................................................................... 11

11. Pygophore in posterior view: lateral lobe of paramere weakly developed, rough, directed to dorsal rim of pygophore ( Fig. 8A View FIGURE 8 ); median limit of paramere touching segment X in rest position ( Fig. 8A View FIGURE 8 ) .................................... N. viridula

11’. Pygophore in posterior view: lateral lobe of paramere more developed,, directed to lateral rim of pygophore ( Fig. 8C View FIGURE 8 ); median limit of paramere not touching segment X in rest position ( Fig. 8C View FIGURE 8 ) ..................................... N. yunnana

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

Nezara

| Ferrari, Augusto, Schwertner, Cristiano Feldens & Grazia, Jocelia 2010 |

Nezara

| Rider 2006: 328 |

| Cassis 2002: 519 |

| Azim 1978: 507 |

| Freeman 1940: 354 |

| Bergroth 1914: 24 |

| Kirkaldy 1909: 115 |

| Distant 1902: 219 |

| Lethierry 1893: 164 |

| Puton 1881: 52 |

| Mulsant 1866: 288 |

| Stal 1865: 192 |

| Fieber 1861: 329 |