Camptomyia Kieffer, 1894

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.11646/zootaxa.4604.2.3 |

|

publication LSID |

lsid:zoobank.org:pub:0BA07364-39ED-4349-98C5-27431A90CEAA |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/4C408780-8A47-FFEC-23A4-6933FDC46B19 |

|

treatment provided by |

Plazi |

|

scientific name |

Camptomyia Kieffer |

| status |

|

Camptomyia Kieffer View in CoL View at ENA

= Niladmirara Fedotova syn. nov.

Major works on Camptomyia in Europe are those by Mamaev (1961), Panelius (1965: 85ff.), Spungis (1989), and Jaschhof & Jaschhof (2013: 328ff.).Also Mamaev & Zaitzev’s (1998) descriptions of ten new Camptomyia from the Far East of Russia have a bearing on the European fauna, as one of those species was later shown to occur in Sweden and others might be unrecognized synonyms. About 26 different Camptomyia have previously been shown to occur in Europe, with almost all of these found in the northern parts of the continent ( Gagné & Jaschhof 2017). Although European Camptomyia have repeatedly been the focus of taxonomic revisions in the past few decades, there remain a number of unresolved issues with species named in the past. As is known, closely related Camptomyia differ mainly in male genitalic characters (the morphology of larvae is generally poorly researched). It is, therefore, crucial that genitalic structures with relevance for species delimation and identification are properly illustrated―an aspiration that is all too often not met in species descriptions published before 2013. In our revision of Camptomyia in Sweden ( Jaschhof & Jaschhof 2013: 328ff.) we had reason to re-illustrate 14 species named by previous authors, and, regrettably, similar redescriptions are needed for almost all the remaining species in Europe, as well as those described from elsewhere. However, several circumstances impede a comprehensive revision of named Camptomyia , first and foremost the circumstance that quite a number of species lack properly prepared specimens, a prerequisite for making both informative illustrations and qualified taxonomic decisions. The resources required to collect fresh specimens would be substantial, considering that the species in question are scattered across several continents. (Even greater efforts would have to be made to obtain fresh specimens for integrative taxonomy.) Those resources are not on the horizon, so the only feasible approach is to revise Camptomyia step-by-step as new material accumulates. This is done here: apart from describing four new Camptomyia , we redescribe three of the named species whose identification has previously been proven problematic.

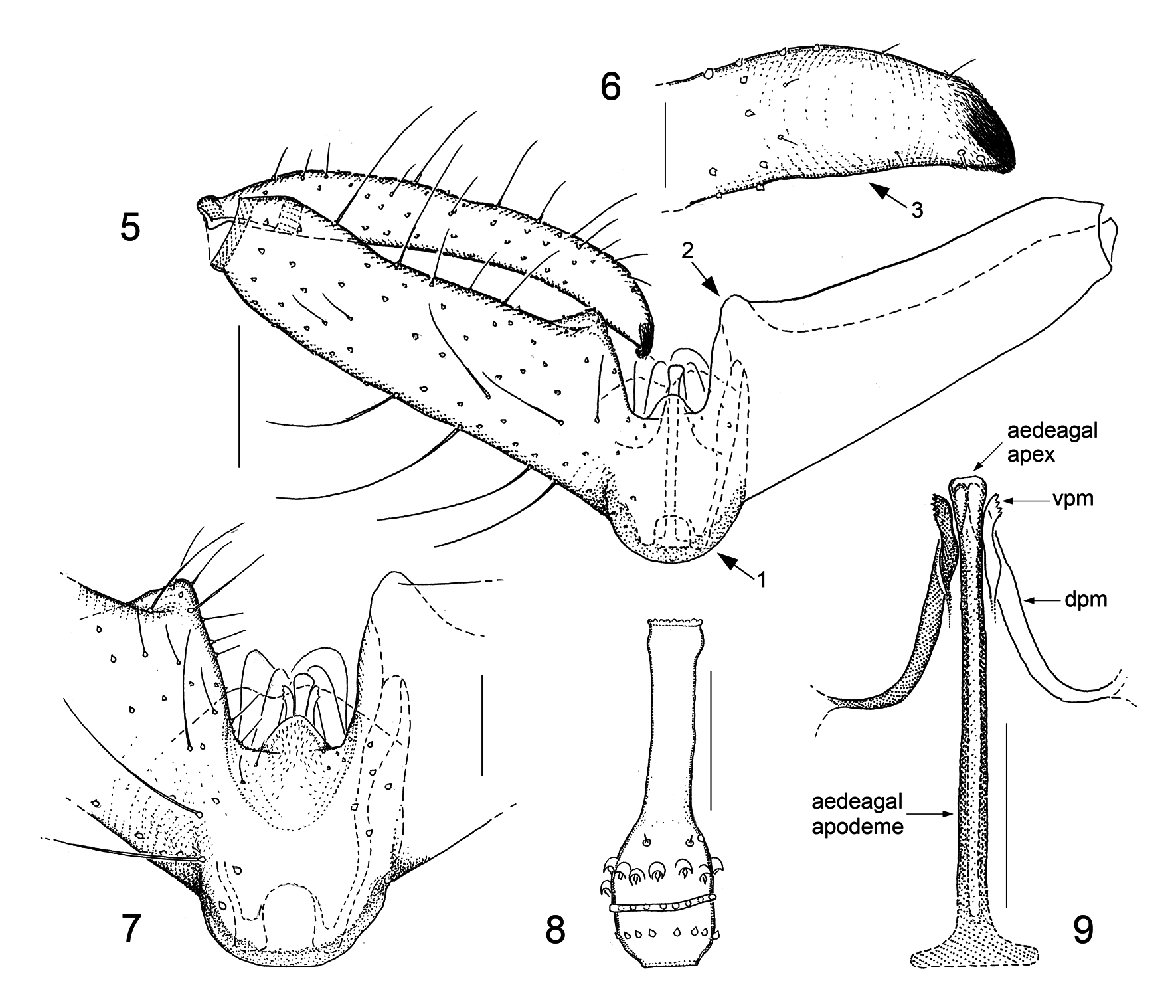

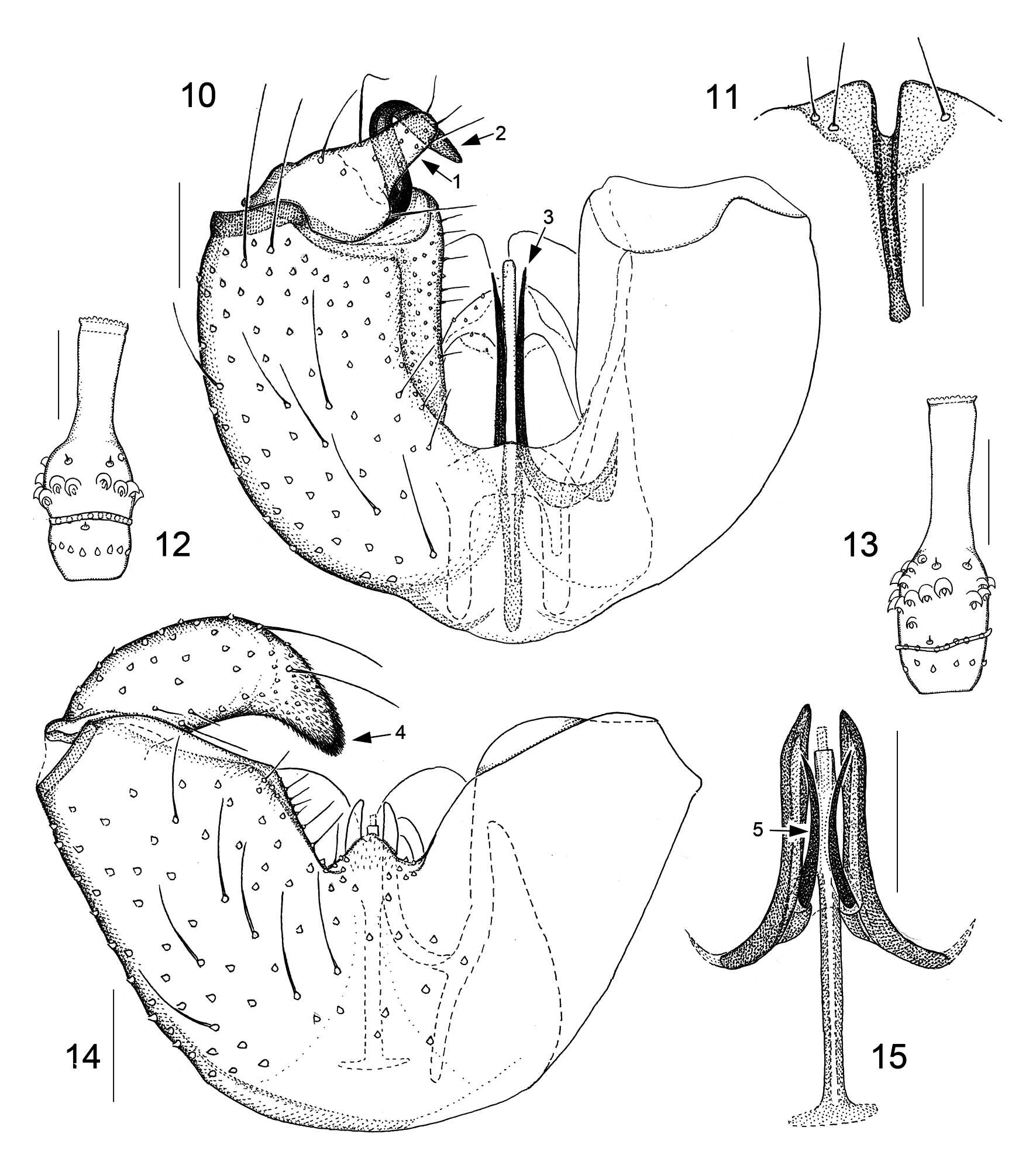

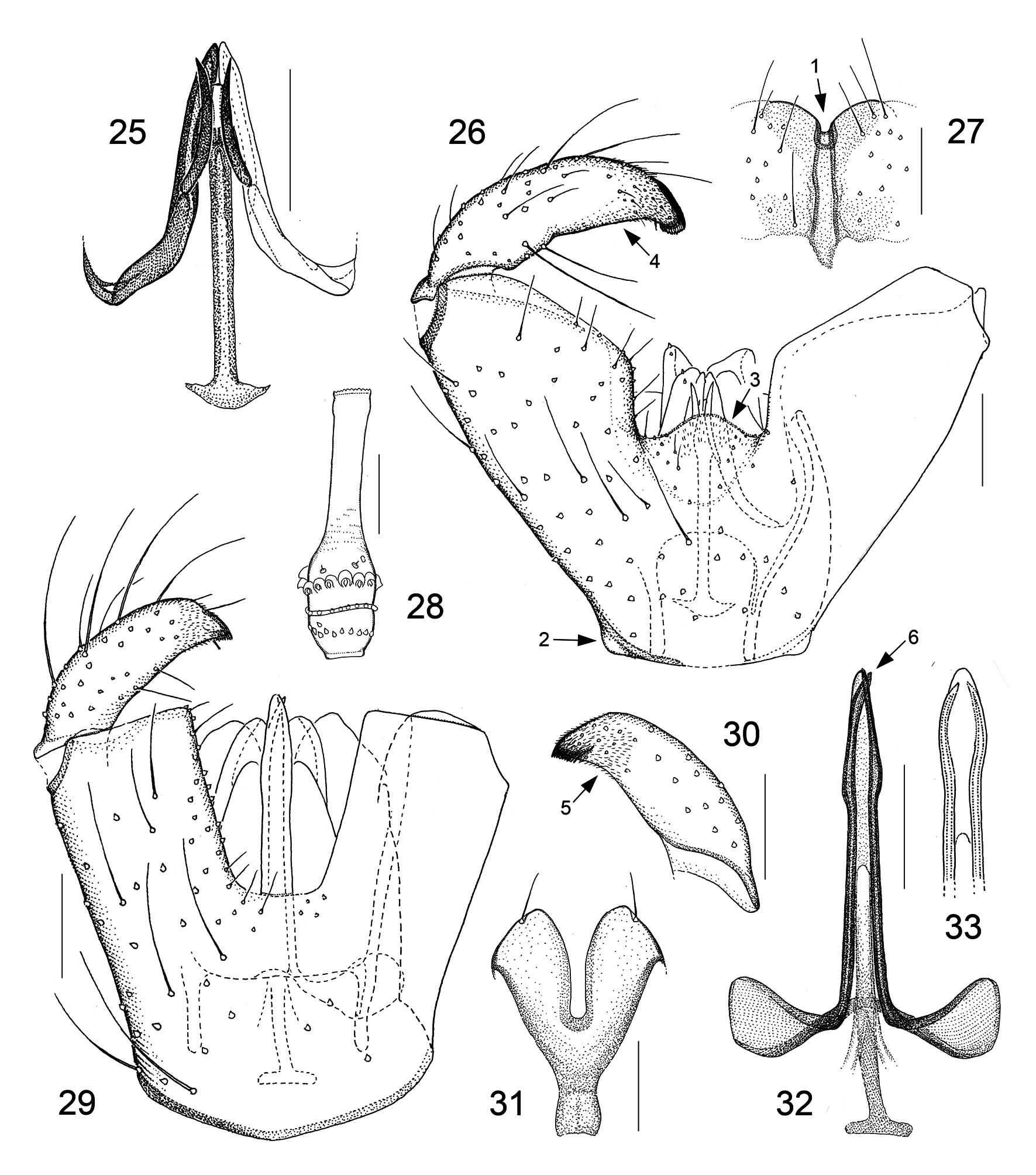

Male genitalic structures are even more diverse in Camptomyia than in Asynapta . This is true for all the genitalic components but especially for the parameres. To get an idea of the parameral diversity in European Camptomyia , one should quickly look over the 15 species figured in our 2013 book ( Jaschhof & Jaschhof 2013: figs 162–176) and be aware that the range of variation indicated there is considerably greater with extra-European species. It is important to note here that the presence of two parameral pairs is obvious, or at least discernible, in most Camptomyia ( Figs 9 View FIGURES 5–9 , 15 View FIGURES 10–15 , 24 View FIGURES 18–24 , 25 View FIGURES 25–33 ); absence of one of the pairs, which is not unusual ( Figs 10 View FIGURES 10–15 , 32 View FIGURES 25–33 ), is explained here by secondary loss. The aedeagus of Camptomyia has, despite considerable interspecific variation, a uniform basic structure, which consists of a well-developed, sclerotized rod—the aedeagal apodeme—and the elongate, sclerotized aedeagal apex ( Fig. 9 View FIGURES 5–9 ). The apodeme is often extended basally to provide space for muscle insertion, with the extension usually resembling a T ( Fig. 9 View FIGURES 5–9 ). The construction of the aedeagal apex is highly variable, both regarding its dimensions and equipment with fine-structures, of which some may lead to remarkably elaborate designs ( Jaschhof & Jaschhof 2013: figs 162B, 170E).

The diversity found in male genitalic structures of Camptomyia has so far proved to be too intricate as to be of use for building a subgeneric classification that is both comprehensive and in accordance with the natural relationships between species. Even a subdivision into groups of similar-looking species, which would facilitate the task of identification, has not yet been achieved. The difficulty is, in brief, to recognize meaningful patterns in a world of overwhelming diversity. On top of this, it is obvious that only fragments of this diversity have been described to date, so that the time is simply not ripe for clustering species in distinct groups, let alone subgenera. Against this background Mamaev’s (1961) proposal of dividing Camptomyia into five subgenera, including Camptomyia sensu stricto, must be regarded as premature. Aside from the fact that as many as five subgenera were needed to accommodate only 11 species, Mamaev’s (1961) subgeneric definitions are vague, with the exception of Camptomyia sensu stricto, which is largely identical with the C. corticalis group of species by Jaschhof & Jaschhof (2013: 332f.). Spungis (1989), in reference to Mamaev’s (1961) proposal, remarked that it would require another five or six subgenera to accomodate all the 24 different Camptomyia known to him from Europe.

Similarly unhelpful seems to us the practice to separate single, somehow conspicuous species from Camptomyia and classify these in discrete, new genera. Examples of this strategy are Eudokimyia and Tenepidosis , two genera introduced by Fedotova & Sidorenko (2005) for two Camptomyia with needle-like copulatory organ, apparently the parameres intimately merged with the aedeagus. This most simplified type of copulatory organ is also found in the Nearctic C. pseudotsugae Hedin & Johnson, 1968 , as well as in an undescribed Camptomyia we have seen from Czech Republic. There are many other parameral types in Camptomyia , including several really outstanding, but none correlates with a particular type of, for instance, gonostylar or gonocoxal structure (an exception here is, as mentioned above, the corticalis group, whose species are likely to form a monophylum). Randomly chosen combinations of characters, as they underlie the generic concepts of Eudokimyia and Tenepidosis (see Fedotova & Sidorenko 2005), could be employed to define genera in any quantity desired―an approach rendering the category of genus pointless.

All the genus-group names introduced by both Mamaev (1961) and Fedotova & Sidorenko (2005) are, for the reasons explained above, regarded as synonyms of Camptomyia (see Gagné & Jaschhof 2017), which does not interfere with the fact that they continue being available should their usefulness be shown in future studies.

The latest, in our view superfluous name introduced for Camptomyia is Niladmirara Fedotova, 2018. In her generic definition Fedotova (2018: 1) referred to eight characters (seven male genitalic) that purportedly differ from the conditions found in Camptomyia —clearly a statement that is not in accordance with the facts. The truth is rather that each of the putative peculiarities of Niladmirara are found here and there in Camptomyia . The new genus was mainly justified by having two pairs of biramous parameres, which is correctly observed, but as argued here, is a plesiomorphous condition found throughout the asynaptine clade, including Camptomyia . On these grounds Niladmirara is treated here as a new junior synonym of Camptomyia . From a technical point of view one has to remark that the type species of Niladmirara, N. metula Fedotova, 2018, is based on a single male whose genitalic structures are severely deformed, apparently as a result of improper handling during the mounting process. In particular the parameres are disrupted and wrested from their natural connections to other genitalic structures, which is evidenced by Fedotova’s (2018) line drawing (fig. 1) and micrographs (figs 25–26). Specimens like this are normally disregarded in taxonomic studies to avoid treating artifacts as putative diagnostic characters. Reviewers of Fedotova’s (2018) work would likely have passed a pertinent comment, provided that someone had been given the chance to evaluate the manuscript before publication.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.