Blarina brevicaudus (Say, 1823)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6870843 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6878330 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/3D474A54-A018-8775-FAF9-AECA15B8F3A2 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Blarina brevicaudus |

| status |

|

Northern Short-tailed Shrew

French: Grande Musaraigne / German: Nordliche Kurzschwanzspitzmaus / Spanish: Musarana colicorta septentrional

Other common names: Giant Mole Shrew, Short-tailed Shrew

Taxonomy. Sorex brevicaudus Say, 1823,

“ Engineer cantonment ... west bank of the Missouri [River] , about half a mile [= 0-8 km] above Fort Lisa, five miles [= 8 km] below Council Bluff, and three miles above the mouth of Boyer’s River,” Nebraska, USA . Restricted by J. K. Jones, Jr. in 1964 to “ Washington County, Nebraska, about five miles [= 8 km] north of the Douglas-Washington county line at a place approximately two miles [= 3 -2 km] east of the present village of Ft. Calhoun.”

Widely used specific name brevicauda is replaced with the original epithet brevicaudus because it is not a Latin adjective, does not require change for gender agreement, and remains valid. Blarina brevicaudus was considered conspecific with B. hulophaga and B. carolinensis by E. R. Hall in 1981, and telmalestes was regarded as a distinct species in the same publication. Blarina hulophaga and B. carolinensis were subsequently recognized as distinct species by S. B. George and colleagues in 1986 and most other publications, while telmalestes has generally been regarded as a subspecies of B. brevicaudus, which was followed by R. Hutterer in 2005. C. A.Jones and colleagues in 1984 speculated that shermani (then recognized as a subspecies of B. carolinensis ) would either be a subspecies of B. brevicaudus or a distinct species, and R. A. Benedict and colleagues in 2006 recognized B. shermani as a distinct species based on morphometrics (being substantially smaller than B. brevicaudus) and the species allopatric distribution, which is followed here although genetic data are needed to confirm this. S. V. Brant and G. Orti in 2002 found that B. brevicaudus was genetically sister to B. carolinensis , with B. hulophaga basal to them both. Brant and Orti in 2003 found that B. brevicaudus consists of two genetic lineages (eastern and western) separated by the Mississippi River, which apparently corresponds with recognized subspecific distributions. Additional investigation into subspecific arrangement of B. brevicaudus is needed. Eleven subspecies recognized.

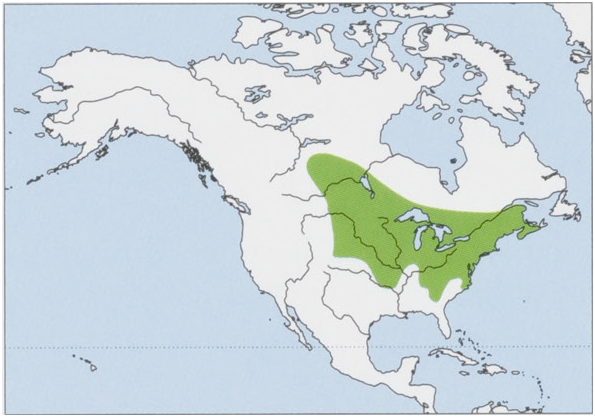

Subspecies and Distribution.

B. b. aloga Bangs, 1902 — Martha’s Vineyard I, off SE Massachusetts (USA).

B.b.angustaR.M.Anderson,1943—SEQuebecandNNewBrunswick(Canada).

B.b.churchiBole&Moulthrop,1942—SEKentucky,SWVirginia,ETennessee,andWNorthCarolina(USA).

B.b.compactaBangs,1902—NantucketI,offSEMassachusetts(USA).

B.b.hooperiBole&Moulthrop,1942—extremeSEQuebec(Canada)andNVermont(USA).

B.b.manitobensisR.M.Anderson,1947—C&SESaskatchewanandSManitoba(Canada),andNNorthDakota(USA).

B.b.pallidaR.W.Smith,1940—NMaine(USA)andC&SNewBrunswickandNovaScotia(Canada).

B.b.talpoidesGapper,1830—S&SEOntarioandSQuebec(Canada),andfromNewEnglandStoNewYorkandNewJersey(USA).

B. b. telmalestes Merriam, 1895 — SE Virginia and extreme NE North Carolina (USA). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 90-114 mm,tail 17-32 mm, hindfoot 13-16 mm; weight 11-30 g. The Northern Short-tailed Shrew is the largest species of Blarina and the largest shrew in the Americas. Snout is pointed but shorter and wider than in other species of shrews. There is little to no secondary sexual dimorphism. Pelage is short, soft, and considerably mole-like in winter and shorter and slightly paler in summer. Dorsal pelage is silvery dark slate gray in winter and paler silvery gray in summer, although its pelage can range from silvery to black. Juveniles have shorter and fuzzier pelage, which can be hard to distinguish from adults in summer. Ventral pelage is a somewhat paler gray, shorter, and denser than dorsal pelage. There is a bare patch of lightly colored skin around diminutive eyes. Albinos have been recorded. Ears are very small and completely concealed by fur; vibrissae are long and white. Tail is less than 30% of head-body length, hairy, and similar in color to dorsal pelage, being faintly bicolored in adults with small tuft at end. Feet are short and broad, with long claws, and are paler than rest of body. Characteristic of the genus, the Northern Short-tailed Shrew has five unicuspid teeth and significantly larger and angular skull than other shrews. All species of Blarina also have reddish teeth from iron deposits in their teeth. All five species are difficult to tell apart, but the Northern Short-tailed Shrew is larger than all the other species and has unique karyotype. The Northern Short-tailed Shrew is one of the few venomous mammals, having submaxillary glands at base of lower incisors that secrete venomous saliva that flows through grooves between two teeth when the individual bites. The toxins in the venom are so far known to include the blarinatoxin (BLTX), a 253 amino acid (aa) peptide; blarinasin, a 252 aa peptide; and soricidin, a 54 aa peptide. BLTX and blarinasin have kallikrein-like proteolytic activity similar to that of lizard venom while soricidin is a paralytic oligopeptide that can block nerve impulses by inhibiting calcium channels. Females have three pairs of inguinal mammae. More than 144 species of endoparasites and ectoparasites have been named from the Northern Short-tailed Shrew, including at least two lice, two leptinid beetles, one cuterebrid fly, 25 fleas, 34 ticks and mites, and many nematodes, trematodes, and cestodes. Chromosomal complement has 2n = 48-50 and FN = 52.

Habitat. Typically, hardwood deciduous forests with deep leaflitter and around edges of ponds and streams but also coniferous forests, open grass and sedge fields, farmhouses, and marshlands. The Northern Short-tailed Shrew is considered a habitat generalist, and it is most notably associated with food availability, while avoiding areas with extreme temperatures and moisture, although moist areas seem preferred. The more northern populations (southern Quebec) have been reported in mature deciduous or coniferous forests and less commonly in fields with tall grasses or sedges. It is occasionally found near homes or shelters and agricultural fields. In dry deciduous forests,it seeks out wetter microhabitats. In eastern Tennessee,it readily inhabits areas with few shrubs, dense overstory, hard ground, and high density of stumps and logs, which are much more specific habitat requirements than those of other populations. In south-eastern Virginia and north-eastern North Carolina (subspecies telmalestes), it inhabits marshy habitats.

Food and Feeding. Northern Short-tailed Shrews are primarily insectivorous, although they are considerably omnivorous and will even eat vertebrates. Earthworms and millipedes are major parts of their diets, along with other arthropods (sowbugs, arachnids, various larval insects, centipedes), various plant material, snails, vertebrates, and fungi (e.g. Endogone ) on rare occasions. Vertebrate prey largely consists of mice and voles, although there are reports of preying on other shrews ( Sorex ), snakes (Thamnophis and Nerodia), young Snowshoe Hares (Lepus americanus), and slimy salamanders (Plethodon glutinosus). To subdue prey, they bite it and hold on while injecting their venom, which paralyzes most invertebrates and small vertebrates and might even kill them. Venom may be fatal to other conspecific shrews, but more research is needed to confirm this. A captive Northern Short-tailed Shrew placed in an enclosure with a vole bit the base of the vole’s skull behind the ears, gnawed at the base of the skull, and roughly dragged the vole around the cage as the vole attempted to escape; the vole died after eleven minutes. Food hoarding occurs relatively often, especially in autumn, winter, and occasionally summer. Insects and earthworms are usually stored alive but paralyzed by venom so for shrew can come back later and consume the prey. During winter, they consume c.43% more food than in summer, which makes hoarding a crucial adaptation for survival over winter. In a study of captive individuals, Northern Short-tailed Shrews cached 86-6% of food they killed, eating ¢.9-4% immediately. The other 3-9% waskilled and subsequently left uneaten. They might also visit bird feeders and take seeds during winter when food is scarce.

Breeding. Reproduction of Northern Short-tailed Shrews occurs from early February to September with two major peaks, one in spring and the other in late summer and early autumn; however, females in estrus can be encountered in as earlyJanuary, and reproductive males have been recorded as late as mid-October. During copulation,a pairis locked together while the female remains active and drags the male behind her. This can last up to 25 minutes (average c.5 minutes). Ovulation is induced by copulation, which takes at leastsix copulations/day and generally occurs 55-71 hoursafter initial copulation. Gestation lasts 21-22 days, and litters have 3-8 young (average c.4-5). Females usually have two litters/season but can have as many as three. Young are weaned by 25 days old, begin to become sexually active at ¢.50 days old, and generally breed at c.65 days old. Females lose all maternal instinct after young are weaned, and young then disperse. Individuals born in spring mature faster than individuals born in autumn, which enables more productive breeding seasons because young born in spring might reproduce within the same season. Most individuals do not survive more than a year, with the oldest captive individual being a male that lived 33 months. Females move their young by dragging them in their mouth or by a behavior similar to caravanning, although caravanning was only recorded for a female with one juvenile. Females generally become more active when pregnant and lactating and will constrict entrances to their nests after young are born.

Activity patterns. Northern Short-tailed Shrews are semi-fossorial and primarily nocturnal, being active throughout the night and into early morning, apparently being most active in early morning and night in summer and earlier in evening in winter. They are only active for c.16% of a 24hour day, and they are active for an average of 4-5 minutes at a time, with bouts ofresting in between activity. They spend the rest of their time resting or sleeping in their nests. They do not spend much time on the surface, preferring to move about their tunnels, but they have been known to climb trees and bird feeders. They do not hibernate but do molt between seasons. Tunnels are usually within the top 10 cm ofsoil but can be as deep as 50 cm. Tunnels are used as runways, and they will dig through rotten logs and use runways of voles and moles instead of making their own. Northern Short-tailed Shrews can dig c.2-5 cm/minute but will stop to take short naps regularly during digging. These runway tunnel systems can be very extensive and honeycomb across an expansive area. In areas with a lot ofleaf litter, burrows can be just under it, and in winter, burrows can extend into snow. Nests are connected to the tunnel system and spherical, ¢.20 cm in diameter, generally lined with vegetation or rarely fur from other mammals such as voles. When sleeping, Northern Short-tailed Shrews usually curl up with their noses and paws tucked undertheir bellies and are restless, twitching while sleeping and changing positions and yawning often. Feces are usually deposited rather neatly outside entrances of nests or on sides of runways but rarely in nests. In captivity, fecal matter was deposited in corners of cages.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Northern Short-tailed Shrew is widespread and abundant. Densities are highly variable and fluctuate readily. Population crashes take place that take several years to recover from. Densities are 1-6-121 ind/ha depending on the region and whether a population crash has occurred, but they usually are 5-30 ind/ha. Home ranges average c.2-5 ha, and an individual's home range usually overlaps with at least one if not many other shrews. Northern Short-tailed Shrews are primarily solitary and non-migratory, only associating with others when mating and rearing young. In captivity, however, when they are housed with familiar individuals, they will sleep in a large pile and constantly attempt to move toward the bottom of the pile. Females and young individuals are less aggressive than males and older individuals. Northern Short-tailed Shrews are mildly territorial, but when captive shrews are put together, one shrew generally ends up eating the other. To defend their territory, they can show aggressive displays and vocalize, and they might also use scent glands to mark theirterritories, although scent marking has not been confirmed. They produce a musky odor from scent glands that might deter predators. In winter, mortality rates can be up to 90%. The Northern Short-tailed Shrew uses echolocation to explore its environment, using ultrasonic clicks to distinguish items and navigate around objects. Echolocation and touch are the main navigational senses, making up for poor vision and underdeveloped sense of smell. Ultrasonic clicks are 30-50 kHz.

Status and Conservation. Classified as Least Concern on The IUCN Red List. The Northern Short-tailed Shrew is abundant, widespread, and well studied, with no major threats throughout its distribution. Studies found that large concentrations of DDT had bioaccumulated in their bodies because of their predatory nature, but this is no longer a threat because DDT is no longer used in large quantities; other toxins might be of concern. Northern Short-tailed Shrews are somewhatsensitive to habitat destruction such as forest clearing, and populations have dramatically decreased after forests were cut. Venom poses no major threat to humans, and if bitten, the area will swell and be considerably painful for a few days. Nevertheless, this venom might have some potential applications, such as reducing epithelial cancers by inducing apoptosis (programmed cell death) within epithelial cells, which is done by inhibiting TRPV6 calcium channels. It might also be used to detect TRPV6rich tumors using shorter peptides derived from soricidin.

Bibliography. Benedict et al. (2006), Bowen et al. (2013), Brandt & McCay (2005), Brant & Orti (2002, 2003), Cassola (2016f), Dimond & Sherburne (1969), Ellis et al. (1978), George et al. (1986), Getz (1989), Hall (1981), Hutterer (2005b), Jones, C.A. et al. (1984), Jones, J.K. (1964), Kurta (1995), Liu Cuicui et al. (2014), Martin (1980, 1981a, 1981b, 1982, 1983, 1984), Merritt (1986), Pearson (1947), Platt (1976), Randolph (1973, 1980), Reid (2006), Robinson & Brodie (1982), Tomasi (1978).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.