Choneziphius planirostris ( Cuvier, 1823 )

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5376445 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03FED57F-FFF8-9F68-83D3-FDFAFBD7FAEC |

|

treatment provided by |

Marcus |

|

scientific name |

Choneziphius planirostris ( Cuvier, 1823 ) |

| status |

|

Choneziphius planirostris ( Cuvier, 1823)

Ziphius planirostris Cuvier, 1823: 352-356 , pl. 27, figs 4-8. — Owen 1870: 5, fig. 2. — Van Beneden & Gervais 1880: pl. 27, figs 4, 5.

Choneziphius planirostris Duvernoy, 1851 : pl. 2, fig. 5. — Gervais 1859: pl. 40, fig. 2. — Abel 1919: figs 575, 576. — Bianucci 1997: pl. 2, fig. 1, pl. 3, fig. 1.

Ziphius cuvieri Owen, 1870: 6 , fig. 3.

Choneziphius trachops Leidy, 1877 : pl. 30, fig. 2, pl. 31, fig. 1.

LECTOTYPE. — The best preserved of the two originals of Cuvier (1823), the anterior part of a skull (found on July 23, 1812, figured in Cuvier [1823: pl. 27, figs 5, 6], and housed at the MNHN).

PARALECTOTYPE. — The second original from Cuvier (1823), a rostrum and the anterior part of the cranium (figured in Cuvier [1823: pl. 27, figs 8, 9] and housed at the MNHN).

REFERRED SPECIMENS FROM ANTWERP. — 14 partial skulls and rostra from the IRSNB referred to Choneziphius planirostris by Abel (1905): IRSNB 3774- M.1881 (partial skull including the rostrum and the anterior of the cranium); IRSNB 3767 (rostrum and anterior of the cranium); IRSNB 3768 (rostrum and anterior of the cranium); IRSNB 3769 (rostrum and anterior of the cranium, except the left supraorbital process); IRSNB 3770 (rostrum and anterior part of the premaxillary sac fossae); IRSNB 3771 (rostrum); IRSNB 3772 (rostrum and anterior of the cranium); IRSNB 3773 (rostrum and anterior of the cranium); IRSNB 3775-M.1883 (rostrum and anterior of the cranium, except the left supraorbital process); IRSNB 3776 (rostrum and anterior of the cranium, except the left supraorbital process); IRSNB 3777-M.1882 (rostrum and anterior of the cranium); IRSNB 3779 (fragment of rostrum and anterior part of the premaxillary sac fossae); IRSNB 3780 (left part of rostrum); IRSNB 3790 (right fragment of rostrum); and four additional undescribed skulls found in the collections of the IRSNB: IRSNB 1719a (rostrum and anterior of the cranium, except the left supraorbital process); IRSNB 1719b (rostrum and anterior of the cranium, except the two supraorbital processes); IRSNB 1719c (rostrum and anterior of the cranium, except the left supraorbital process); IRSNB ED001 (rostrum and anterior of the cranium, found in a box with the skull IRSNB ED002- M.1885 and with a common label: “ Choneziphius planirostris – Et.: Anversien – Loc.: Steendorp – Don Delheid – Reg. I.G. 8289”. One of these two skulls was cited in Delheid [1896] and was found in 1888 near Rupelmonde – this is probably the skull of C. planirostris IRSNB ED 001, judging by the presence of fragments of the label’s rope on this skull).

TYPE HORIZON. — The remarks of M. de la Jonkaire cited in Cuvier (1823: 352, 353) are not clear enough to identify a precise stratigraphic level. However, a specimen from the private collection of P. Gigase was found in the upper Miocene Deurne Sands (P. Gigase pers. comm. 2002).

TYPE LOCALITY. — Antwerp, “bassin du port, […] à quatre cents mètres de la rive droite de l’Escaut, […]” ( Cuvier 1823: 353).

EMENDED DIAGNOSIS. — A species-level diagnosis seems difficult to obtain, because the only well known species of the genus is Choneziphius planirostris . Few differential characters are therefore available. This ziphiid species of moderate size is smaller than Ziphius cavirostris . It differs from C. liops in a more elongated, less pointed rostrum, with the lateral margins roughly parallel on most of its length. It differs from C. macrops in its smaller size and a rostrum relatively higher and narrower (see Table 2).

DISCUSSION

The rostrum from the Red Crag of Suffolk named Ziphius planus by Owen (1870: pl. 2, fig. 1) is referred to Choneziphius planirostris , as suggested by Abel (1905). This fragment has the large asymmetrical excavation of the premaxillary sac fossae and is similar to the specimens of Antwerp IRSNB ED001 and IRSNB 1719b.

An isolated periotic from Suffolk was placed by Lydekker (1887: pl. 2, fig. 7) in C. planirostris , but no ear bone-skull association is known for the genus, while several species of ziphiids are present in the Red Crag. This periotic is therefore placed in Ziphiidae incertae sedis.

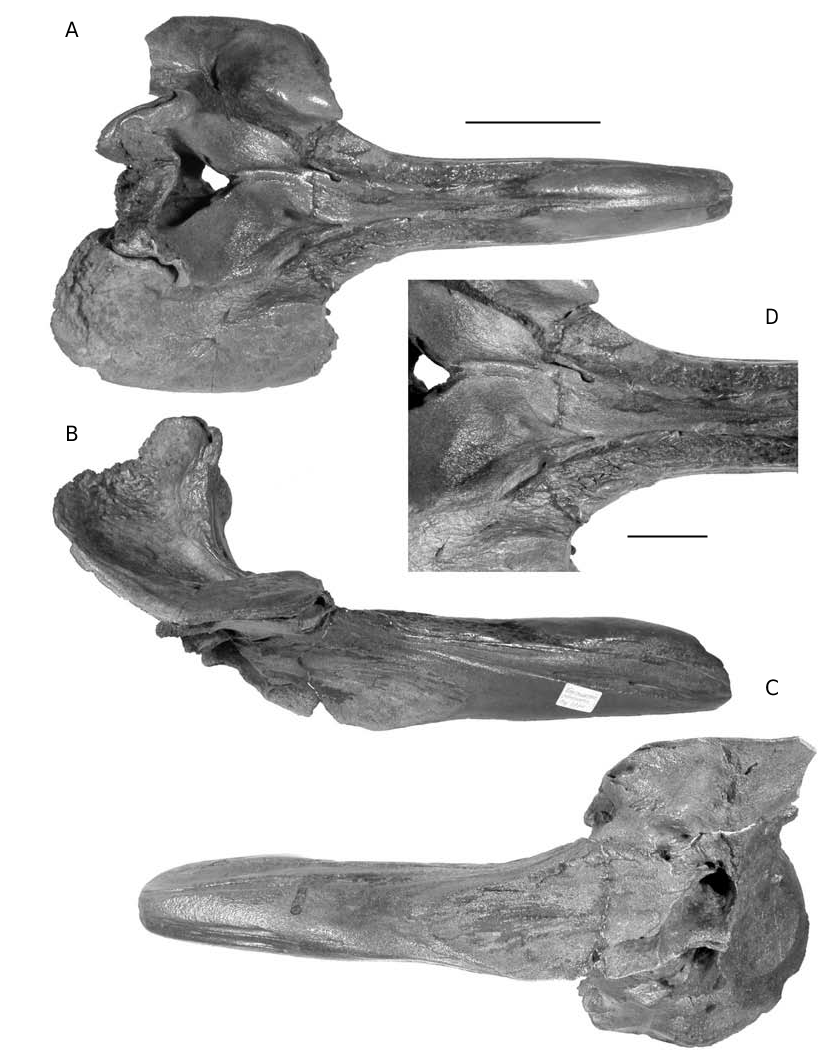

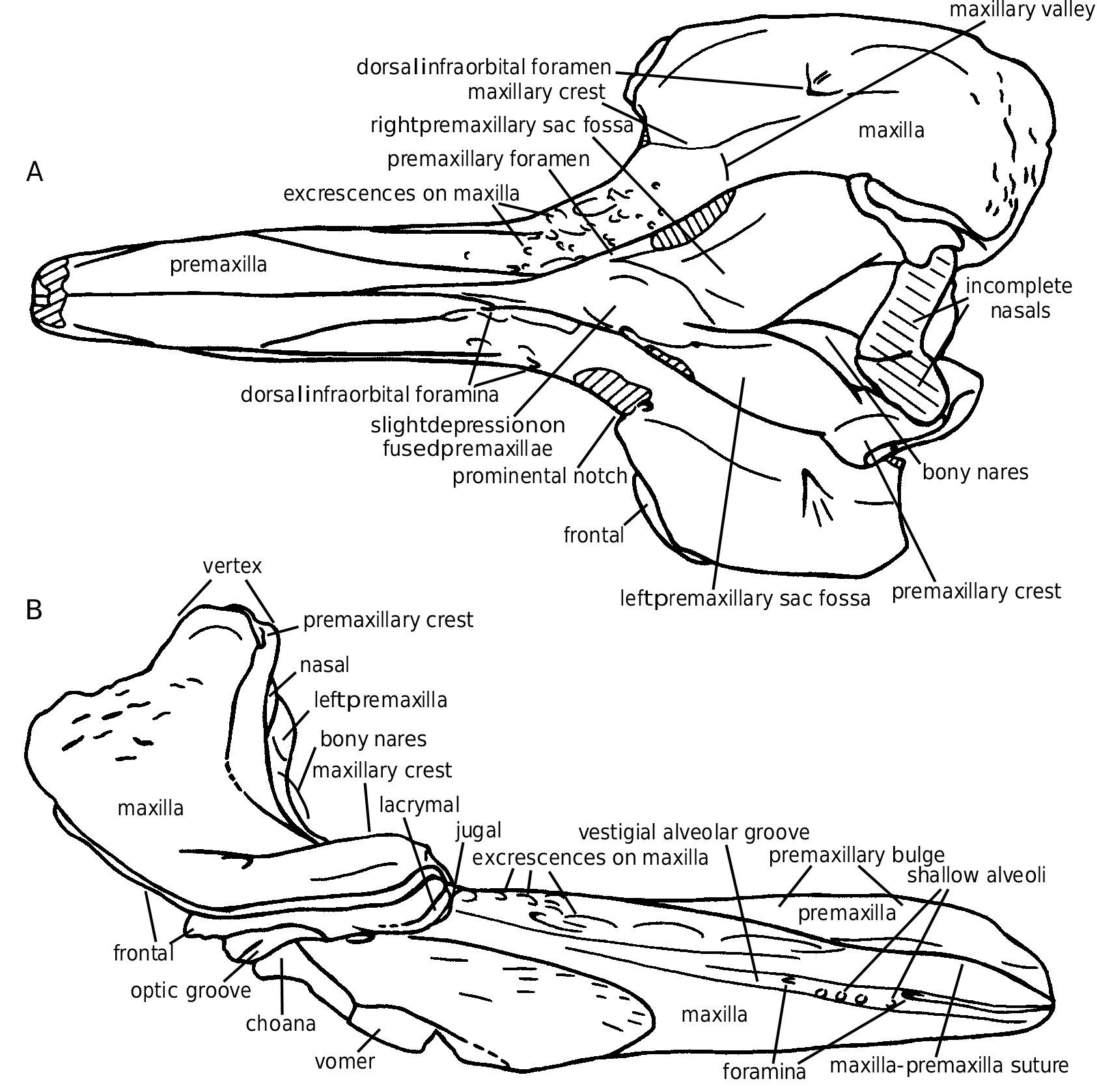

DESCRIPTION ( FIGS 16-19 View FIG View FIG )

This species is only known by anterior parts of skulls, usually including the complete dense rostrum and the anterior of the cranium, with the elevated vertex. No basicranial parts, teeth, mandibles or ear bones are known. Abel (1919: figs 575, 576) provided a reconstruction of the skull, including the unknown basicranium and pterygoids, probably inspired from the extant Ziphius morphology.

The rectilinear rostrum has a length ranging from 297 to 415 mm ( Fig. 21) and is either roughly as high as wide or slightly higher; the width of the cranium at the level of the postorbital processes ranges from 310 to 324 mm (only four skulls of the IRSNB measured) (see Table 2).

Premaxilla

The premaxillae occupy the dorsal face of the rostrum on the first third of its length. They are dense, dorsally thickened (pachy-osteosclerotic), and medially fused, dorsally closing the mesorostral groove ( Figs 16A View FIG ; 17A View FIG ). A reduced longitudinal tunnel is maintained, with a transverse diameter at apex of 10-11 mm. The rostral prominence of the premaxillae narrows posteriorly, and, at the two-thirds of the rostrum length, the closely joined premaxillae only occupy the median third of the rostrum width, as a slightly depressed surface between the maxillae. The longitudinal position of the highest point of the premaxillary prominence, usually close to the apex, is sometimes more posterior, for instance on IRSNB 3777-M.1882 or IRSNB 3773, with a variable width. The surface of this area is often worn (post-mortem). Nevertheless, on the left side of the rostrum IRSNB 3777-M.1882 at least five distinct lami- nae, roughly horizontal, demonstrate the growth process of this portion of the premaxilla (see Fig. 18A). A similar periodical laminar growth pattern is noticed on the vomer of the fossil Mesoplodon longirostris (pers. obs.) and the extant M. carlhubbsi ( Heyning 1984) . The lami n a e a r e n o t v i s i b l e o n t h e o t h e r s k u l l s o f Choneziphius planirostris , but the smallest rostrum of the collection, 118 mm shorter than the largest, has already well developed thickened premaxillae. This might indicate that the development of this thickening starts early in the life of the individual – even if the relative age of the different specimens is difficult to assert because of the usually strong osteosclerosis, closing the sutures.

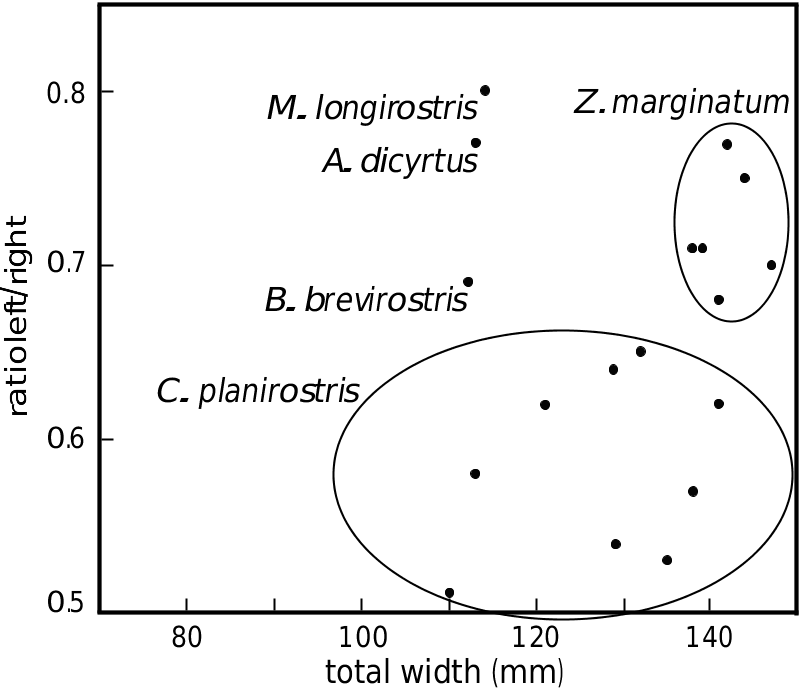

The premaxillary sac fossae are characteristic: the right fossa is much wider than the left, with a ratio between the maximum widths ranging from 0.5 to 0.66 ( Table 2; Fig. 25 View FIG ). The two fossae, strongly concave, are anteriorly hollowed by a deep canal, wider on the right fossa, leading to a large anteriorly directed foramen, at the level of the prominental notches (sensu Heyning 1989a, medial to the antorbital notches; = inner notches

A sensu Harmer 1924) ( Figs 16D View FIG ; 17A View FIG ). The roofing of this foramen is variable: several rostra (e.g., IRSNB 3776) show a dorsally open sulcus for more than 70 mm anteriorly. The two deep premaxillary sac fossae are separated by a prominent asymmetrical platform of the joined premaxillae, posteriorly narrowing with a strong deviation towards the left side. This platform, sometimes narrow and acute can also be wider and lower, with a depressed anterior part, at the level of the prominental notches. This shallow median depression might be interpreted as equivalent to the prenarial basin of the adult males of Ziphius , essentially filled with the right nasal plug ( Heyning 1989a). The dorsal elevation of the premaxilla to the vertex is strong from the premaxillary foramen towards the vertical transverse premaxillary crest. The crest is moderately thickened, rectilinear and anterolaterally directed (by twisting of the narrowest portion of the ascending process of the premaxilla). The dorsal portion of the anterior surface of the left ascending process, much narrower than the right, shows a clear corner with the medioanteri- or surface of the bone. The anterior surface, corresponding in extant ziphiids to the support of the left posterior nasal sac ( Heyning 1989a), is therefore reduced relatively to the right side, as in Ziphius . The bony nares are triangular and asymmetric, with a longer and more oblique right side of the triangle.

Maxilla

Posterolaterally to the rostral prominence of the premaxillae, the maxilla forms a roughly horizontal surface, sometimes laterally twisted on its a n t e r i o r p o r t i o n. A m a i n c h a r a c t e r i s t i c o f Choneziphius planirostris is the covering of that surface by series of dorsoanteriorly directed p r o m i n e n t e x c r e s c e n c e s a n d i r r e g u l a r i t i e s. However, this character is far from consistent within the species: these structures are sometimes completely absent as on the lectotype, reduced as on the skull IRSNB 3773, or much developed, on both sides of the paralectotype ( Cuvier 1823: pl. 27, fig. 7) for example. They can also be asymmetric, and in this case they are always better developed on the right side (e.g., only present on the right maxilla of IRSNB 3777-M.1882, Fig. 18A), and this asymmetry is more pronounced posteriorly, in front of the antorbital notches. No relation with the ontogeny could be found for this variability. In extant ziphiids, such as Ziphius and Mesoplodon , the dorsal surface of the maxilla on the rostrum corresponds to the main area of insertion for the rostral muscles, extending partially dorsally and medially onto the melon (see Heyning 1989a: fig. 8). The irregularities in Choneziphius planirostris might be linked to a more efficient fixation of the muscles on the surface. Furthermore, more developed excrescences on the right side of several skulls might well indicate more powerful muscles compared to the left. In extant odontocetes, the melon is usually set asymmetrically, slightly off to the right side; the fatty core of the melon extends posteriorly into the right nasal plug, more than into the left, and, in the adult males of Ziphius – the closest extant genus to Choneziphius , the right nasal plug is much enlarged ( Heyning 1989a).

In lateral view, the rostral lateral suture between maxilla and premaxilla is visible along most of its path, reaching or closely approaching the apex of the rostrum, going distinctly downwards for the last centimetres. The alveolar groove is sometimes shallow, with weak marks of small alveoli still visible in several places and with anterior foramina opening forward into narrow grooves (e.g., IRSNB 3774-M.1881). On other specimens, the alveolar groove is closed at some levels and presents a deep narrow furrow at others (e.g., IRSNB 3773).

The ventral surface of the rostrum is strongly ossified, with poorly visible sutures. The vomer appears between the maxillae some centimetres anteriorly to the palatines and vanishes before the apex of the rostrum. Several pairs of foramina are present along the median sutures from the medi- an margins of the palatines until the anterior surface of the rostrum, where a pair of longitudinal larger foramina is present, ventrolaterally to the anterior opening of the mesorostral tunnel.

The anterior margin of the supraorbital process is incised by two notches: the prominental notch and the more lateral and slightly posterior antorbital notch, often more distinct. Those two notches are separated by a maxillary tubercule (sensu Heyning 1989a). The latter is followed posteriorly by a high and wide longitudinal crest, sometimes present almost until the posterior bor- der of the maxilla (e.g., IRSNB 3773), but generally quickly lowering and vanishing, before (or at the level of) the postorbital process. The left crest is slightly more developed than the right. When one of the supraorbital processes is lost by postmortem damage, this is always the left. The medial slope of the crest is much steeper than the lateral, forming the lateral wall of a deep and wide valley ( Figs 16A View FIG ; 17A View FIG ). This maxillary valley, separating the crest from the premaxillary sac fossa, is partially roofed by the overhanging acute outer margin of the premaxilla. The anterior part of the valley is pierced by a medium-size foramen anterolaterally followed by a sulcus towards the prominental notch. A large posterior dorsal infraorbital foramen, sometimes coupled with a small- er, pierces the supraorbital process of the maxilla into or in the prolongation of the maxillary crest. In lateral view, the roughly horizontal supraorbital process presents a thin maxillary plate, anteroventrally curving around the thicker frontal, and contacting the only partially fused jugal and lacrimal on the anterior margin. At the level of the preorbital process, the differentiated erosion of the bone due to the inclusion of more porous bone between osteosclerotic layers sometimes preserves upper and lower thin plates of the frontal separated by a deep excavation. The same structure is observed on the underlying lacrimal, giving this area a multi-folded pattern.

The frontals are always lost on the vertex, by postmortem damage. The contact between maxilla and premaxilla on the vertex is folded and pierced by a series of vertical foramina.

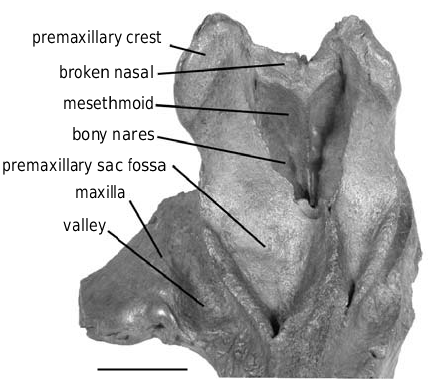

Nasal

The nine skulls of the IRSNB for which the vertex is partially preserved show an identical type of break for the nasals: those bones are only preserved for a short distance dorsally to the upper limit of the mesethmoid ( Fig. 19 View FIG ). This common feature, contrasting with the usually completely preserved nasals of Ziphirostrum marginatum , implies a different morphology of the nasals. One possibility is that the dorsal part of the nasals was less dense in Choneziphius , and therefore more easily eroded. A n o t h e r h y p o t h e s i s, w h e n c o m p a r i n g C h o - neziphius to Ziphius , is that the nasals of Choneziphius were dorsoanteriorly elongated, overhanging the external nares in a way similar to Ziphius . On such eroded skulls, such nasals are more likely to have been broken before burial than are the short nasals of Ziphirostrum , which are somewhat protected between the premaxillary crests. If this is the case, Choneziphius might also possess a cartilage filling the cleft between the premaxillary crest and the nasal, as in Ziphius (see Heyning 1989a: fig. 20). In Ziphius , the surface where the cartilage contacts the nasal and the premaxilla is rough, excavated by small grooves and pits. Even if on several individuals of Choneziphius planirostris the corresponding surface is also irregular (e.g., IRSNB 3774-M.1881), those irregularities could clearly be related to the structure seen in Ziphius ; the premaxilla is usually too worn at that level to allow a description of the surface.

Mesethmoid

The sides of the sagittal keel of the mesethmoid are pierced at mid-height by one or two pairs of small olfactory foramina.

Palatine

The palatine is not always distinct; it reaches an anterior level at least 130 mm anterior to the antorbital notch. While the pterygoid is totally lost, the shape of the large anterior pterygoid sinus fossa can be seen, hollowing most of the surface of the palatine.

At the junction between the rostrum and the roof of the orbit, the infraorbital foramen is a shallow fossa pierced by a posterolateral foramen (= sphenopalatine foramen) and a slightly larger anteromedian foramen. A sulcus starts from the fossa towards the antorbital notch, and another leads to a vertical foramen emerging in the lateral wall of the choana.

COMMENTS ON THE SKULL IRSNB 3778-M.1884 REFERRED HERE TO CHONEZIPHIUS MACROPS ( LEIDY, 1876)

The large and robust partial skull IRSNB 3778- M.1884 ( Fig. 20 View FIG ), placed in Choneziphius planirostris by Abel (1905), has a rostrum more than 80 mm longer than the largest C. planirostris of the IRSNB ( Fig. 21). Moreover, this specimen differs from members of C. planirostris by the following characters: the much flatter and wider rostrum, especially at its base with more acute laterodorsal edges; the more pronounced median separation between the premaxillary sac fossae; the relatively lower anterior thickening of the premaxillae; and the median margins of the premaxillae separated on the apical 80 mm. The Choneziphius characters of this specimen are: the excavation of the premaxillary sac fossa anteriorly extended by a partially roofed sulcus; the irregular subhorizontal dorsal surface of the maxilla on the proximal part of the rostrum; and the anterior thickening of the premaxilla, dorsally roofing the mesorostral groove. This rostrum shows interesting similarities with the holotype of Proroziphius macrops sensu Leidy, 1876 (figured in Leidy 1877: pl. 32, figs 1, 2), from the Phosphate Beds

A of South Carolina. Those two specimens (holotype of P. macrops and IRSNB 3778-M.1884) exhibit roughly the same kind of preservation and their proportions are more similar to each other than to Choneziphius planirostris . A comparison of the measurements provided by Leidy (1877) for the holotype of Proroziphius macrops (transformed from inches to millimetres) with IRSNB 3778-M.1884 is given here ( Table 3). The rostrum of IRSNB 3778-M.1884 is somewhat flatter at every level but this difference is not sufficient to separate the two skulls; both of them are therefore included in a same species of the genus Choneziphius , C. macrops ( Leidy, 1876) . That species differs from C. planirostris by the larger size of the relatively wider and flatter rostrum.

B

The second specimen of Choneziphius planirostris described by Cuvier (1823: pl. 27, figs 7, 8) is also larger, with a rostrum longer than 400 mm. The rostrum is somewhat wider and flatter than on the other specimens, with the subhorizontal irregular surfaces of the maxillae roughly covering three quarters of the length of the rostrum, and a narrower median elevation of the premaxillae. However, this skull shares the morphology of the premaxillary sac fossae of the species C. planirostris (even if the right plate is deep and wide) and is maintained in that species. This might give an ontogenetic direction to the intraspecific variation of several features, for instance the anterior spreading of the subhorizontal irregular surface of the maxilla and the excavation of the right premaxillary sac fossa. This argument is however not so clear among smaller individuals.

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

Genus |

Choneziphius planirostris ( Cuvier, 1823 )

| Lambert O. 2005 |

Ziphius cuvieri

| OWEN R. 1870: 6 |

Ziphius planirostris

| OWEN R. 1870: 5 |

| CUVIER G. 1823: 356 |