Pongo pygmaeus (Linnaeus, 1760)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6700973 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6700563 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03FA8785-4008-9F6B-FF4E-F707FB4CBD9E |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Pongo pygmaeus |

| status |

|

Bornean Orangutan

French: Orang-outan de Bornéo / German: Borneo-Orang-Utan / Spanish: Orangutan de Borneo

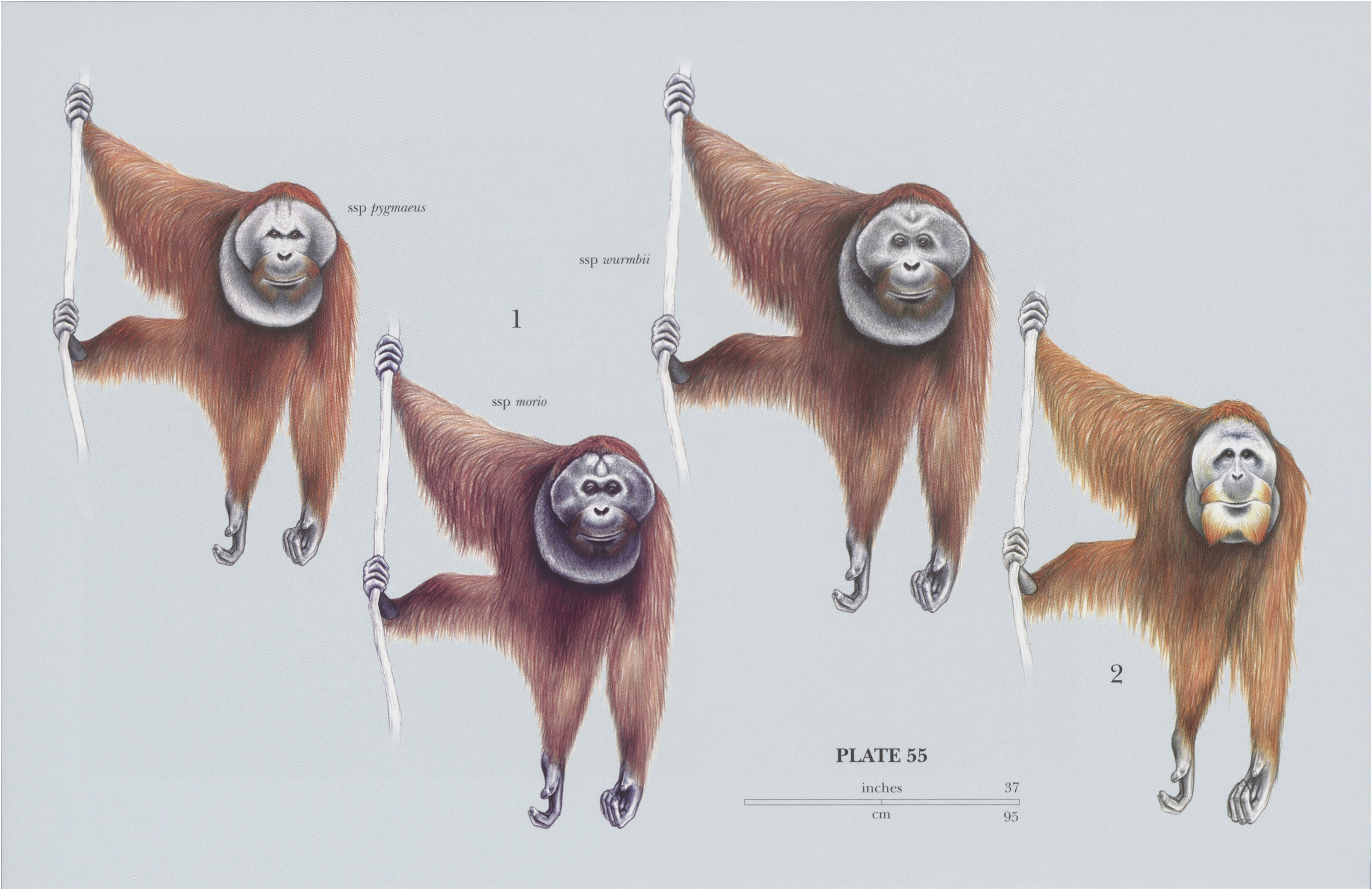

Other common names: North-east Bornean Orangutan (morio), North-west Bornean Orangutan (pygmaeus), Southwest Bornean Orangutan (wurmbii)

Taxonomy. Simia pygmaeus Linnaeus, 1760 View in CoL ,

Indonesia, Kalimantan, Landak River .

Three subspecies are recognized.

Subspecies and Distribution.

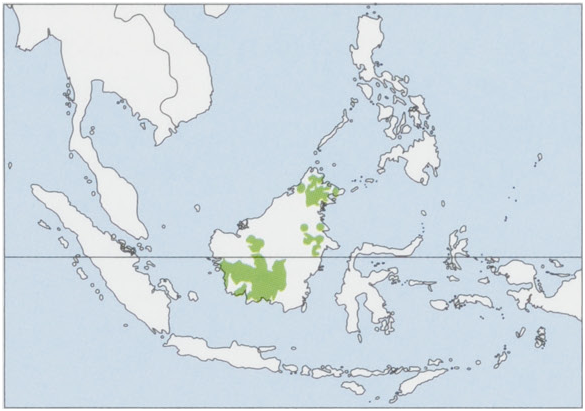

P. p. wurmbii Tiedemann, 1808 — S Indonesian Borneo (S West & Central Kalimantan provinces). View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 96-97 cm (males) and 72-85 cm (females); weight 60-85 kg (flanged males), 30-65 kg (unflanged males), and 30-45 kg (females). The Bornean Orangutan displays extreme sexual dimorphism. Males continue to get heavier as they get older and can exceed 100 kg. It is typically darker than the Sumatran Orangutan ( Pongo abelii ), being orange to brown, or maroon as adults and with somewhat stringier hair; Bornean Orangutans also tend to be stouter and stockier. Fully mature adult males develop a short beard and protruding cheek pads or “flanges” that are covered with tiny red-brown hairs. Males exhibit bimaturism, existing in two adult morphs: flanged and unflanged. Throat sac of flanged males is highly developed, creating a prominent double chin. Faces of the infants are pink, darkening with age. Prominent eye-rings of pale skin are typical of both orangutan species, but Bornean Orangutans keep these rings throughout adolescence.

Habitat. Mature riparian, freshwater swamp, peat-swamp, lowland dipterocarp, and hill dipterocarp forest up to elevations of 500 m (occasionally up to 750 m); also young and old secondary forest, forest patches in mosaic landscapes, and occasionally montane forest. Bornean Orangutans now occur in fragmented and isolated populations. Large rivers and mountains act as impassable natural barriers that limit their dispersal, but current fragmentation is largely a product of forest destruction by humans. They are most abundant in lowland forest below 500 m elevation. Flood-prone riparian and freshwater swamp forests and peat swamps produce more regular and consistent fruit crops than dryland dipterocarp forests, and they have the highest densities of Bornean Orangutans.

Food and Feeding. Diets of Bornean Orangutans are mainly fruit, supplemented with leaves, shoots, inner bark, seeds, pith, flowers, soil, herbaceous vegetation, invertebrates (especially termites, ants, and some caterpillars), and very occasionally small vertebrates. They consume parts of more than 200 plant species. Borneo experiences extreme seasonal fluctuations in fruit production due to poor soils and annual and supra-annual seasonal changes. Supra-annual cycles are caused by El Nino/La Nina — oscillations in the temperature of the surface of the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean. In El Nino years, droughts and food scarcities are severe and result in prolonged reliance on “fallback foods,” particularly inner bark of trees. The Bornean Orangutan’s jaw and tooth enamel are designed for frequent consumption of resources with hard tissues, such as bark and seeds. During periods of fruit abundance, orangutans gorge themselves on succulent fruits and dipterocarp seeds, putting on extra fat reserves that sustain them in times of food scarcity.

Breeding. Fully flanged adult male Bornean Orangutans and the smaller unflanged males are both capable of reproducing. Females usually give birth to their first infant at c.15 years old. Females have a menstrual cycle of 28-30 days. Mate choiceis largely a female prerogative. Around the time of ovulation, females are usually attracted to the “long calls” of dominant flanged males. If she chooses, she can avoid a flanged male in her vicinity, because she is more agile in the canopy at only one-half the size of the male. Unflanged adult males often force females to mate and can catch them more easily because they are agile and about the same size. Females may initiate, and be the more active partner in, consortships with adult males. A pair may consort for several consecutive days, copulating repeatedly and in various positions, including ventroventral. On average, a female will give birth to 4-5 offspring during her lifetime; the interval between births is 6-1-7-7 years. After a gestation of ¢.254 days,a single infant is born, although twins have been reported in the wild. An infant’s abdomen is sparsely covered with hair, and its face may have a gray-bluish tinge that later turns to pink around the nose and eyes. It clings to the ventral surface of its mother for at least one year, and it may then ride on her back until weaned. During the period of maternal dependency, from birth to weaning, immature Bornean Orangutans learn which foods are safe to eat by observing their mothers and sharing her foods. They also begin to build a mental map of the forest habitat in their mother’s home range. Weaning of Bornean Orangutans is usually completed before the fifth year of infancy, after which they are classified as juvenile. Young individuals become increasingly independent of their mother after the next infant is born, but they may still seek her protection until about 7-8 years old, after which both males and females disperse.

Activity patterns. The Bornean Orangutan is diurnal and mainly arboreal. Orangutans are the largest arboreal animals in the world and are well adapted to life in the canopy. They spend the first part of the day feeding, rest around the middle of the day, and then resume feeding and traveling until the end of the day when they prepare night nests. Bornean Orangutans make day nests less often than Sumatran Orangutans. Flanged male Bornean Orangutans rest the most and travel the least ofall age-sex classes. Males move more widely than females. Males occasionally travel on the ground, mainly when the forest canopy is disrupted, and possibly feel free to do so because of an absence of Tigers (Panthera tigris) on the island. In general, Bornean Orangutans are less sociable than their Sumatran counterparts, and this may be due to the comparatively lower food productivity of forests on Borneo, and thus greater feeding competition. Bornean Orangutans in captivity display cognitively complex behaviors such as tool use; these behaviors were long thought absent in the wild but have now been reported.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Most adult male Bornean Orangutans lead a semi-solitary existence in a large home range that overlaps with 3-4 adult females, each with 1-2 dependent offspring. Flanged males advertise their location to females and other males by regularly emitting long calls. Within a given area, there is normally one dominant flanged male, who is largely intolerant of other adult males in his vicinity. Unflanged males remain silent, which they use as a “stealth” strategy to avoid flanged males and to gain access to females. In general, male home ranges overlap, but dominant males show a tendency to remain in a specific area of forest while subordinate males travel more widely. Adults of the opposite sex come together only for brief consortships. Two adult females will occasionally travel together for a few days (they are usually related), and several adolescents or unflanged males may associate with each other or with an adult of either sex temporarily. Average adult female feeding party size is 1-1-3 individuals. Flanged males usually avoid each other and react aggressively if they come into close proximity. Both sexes disperse at adolescence and leave their mother’s home range, although young females generally remain close to their mother’s home range as they mature; young males disperse farther. Average densities in the Bornean forests are 1-3 ind/km?.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The IUCN Red List, along with the three subspecies. The Bornean Orangutan is fully protected under both Malaysian and Indonesian law. Although some major populations of Bornean Orangutans are found in protected areas, it is now well established that the vast majority live outside of them, in forests that are already being, or are slated to be, exploited for their resources (timber, coal, or gold) or converted to agriculture (notably for oil palm plantations). In addition, hunting for meat and the pet trade remain major threats across most of Borneo, especially in the interior. In some areas, hunting has probably been directly responsible for local extinctions. Orangutans living in close proximity to plantations are likely to raid crops, for which they are persecuted as pests and shot by crop owners. There has been an estimated decline of well over 50% in the overall population of Bornean Orangutans during the last 60 years, and this decline is expected to continue at its present rate due to continuing forest loss. Fire is another notable threat throughout Borneo. Fires destroyed 90% of Kutai National Park in 1983 and 1998, reducing its orangutan population from ¢.4000 individuals to only c¢.600 individuals. In Central Kalimantan, more than 4000 km? of peatland forest burned in 1997-1998 and an estimated 8000 orangutans died, representing a 33% loss of the species in just one year. Similarly, drought in Central Kalimantan is thought to have killed hundreds of orangutans in six months of 2006. Because of their close phylogenetic proximity, orangutans and people are susceptible to similar diseases, and interspecific contamination is a recognized threat. The most recent population estimate for the Bornean Orangutan, obtained between 2000 and 2003, was 45,000-69,000 individuals living in ¢.86,000 km* of habitat. Nevertheless, the inaccessibility of much of their range and poorvisibility in dense forests, combined with the low densities, semi-solitary habits, and cryptic nature of Bornean Orangutans, makes surveying them with precision difficult. Currently, no more than 16% of the Bornean Orangutan’s habitat is protected. Where logging has occurred and forests are fragmented, conservation measures must be taken to create corridors and prevent genetic isolation, allowing gene flow between geographically separated subpopulations.

Bibliography. Ancrenaz, Ambu et al. (2010), Ancrenaz, Gimenez et al. (2005), Ancrenaz, Goossens et al. (2004), Bruford et al. (2010), Goossens, Kapar et al. (2011), Goossens, Setchell et al. (2006), Harrison et al. (2009), Husson et al. (2009), Knott et al. (2009), Lyon (1907, 1911), Markham & Groves (1990), Marshall et al. (2006), Meijaard, Buchori et al. (2011), Meijaard, Mengersen et al. (2011), Morrogh-Bernard, Husson et al. (2009), Morrogh-Bernard, Morf et al. (2011), Muehlenbein & Ancrenaz (2009), Muehlenbein et al. (2010), van Noordwijk et al. (2009), Russon, Wich et al. (2009), van Schaik et al. (2009), Singleton et al. (2009), Taylor (2009), Wich, Utami-Atmoko et al. (2004), Wich, Vogel et al. (2011), Wich, de Vries et al. (2009).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.