BOSELAPHINI Knottnerus-Meyer, 1907

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5373109 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03CF87E7-231D-176B-FD4D-FA1FDB53F965 |

|

treatment provided by |

Marcus |

|

scientific name |

BOSELAPHINI Knottnerus-Meyer, 1907 |

| status |

|

Tribe BOSELAPHINI Knottnerus-Meyer, 1907

Sokolov (1953) created a new subtribe Tragocerina for the fossil antelopes Tragocerus Gaudry, 1861 , Miotragocerus Stromer, 1928 , Paratragocerus Sokolov, 1949 and Sivaceros Pilgrim, 1937 , but the monophyly of this group is questionable. Moyá-Solá (1983) defines the

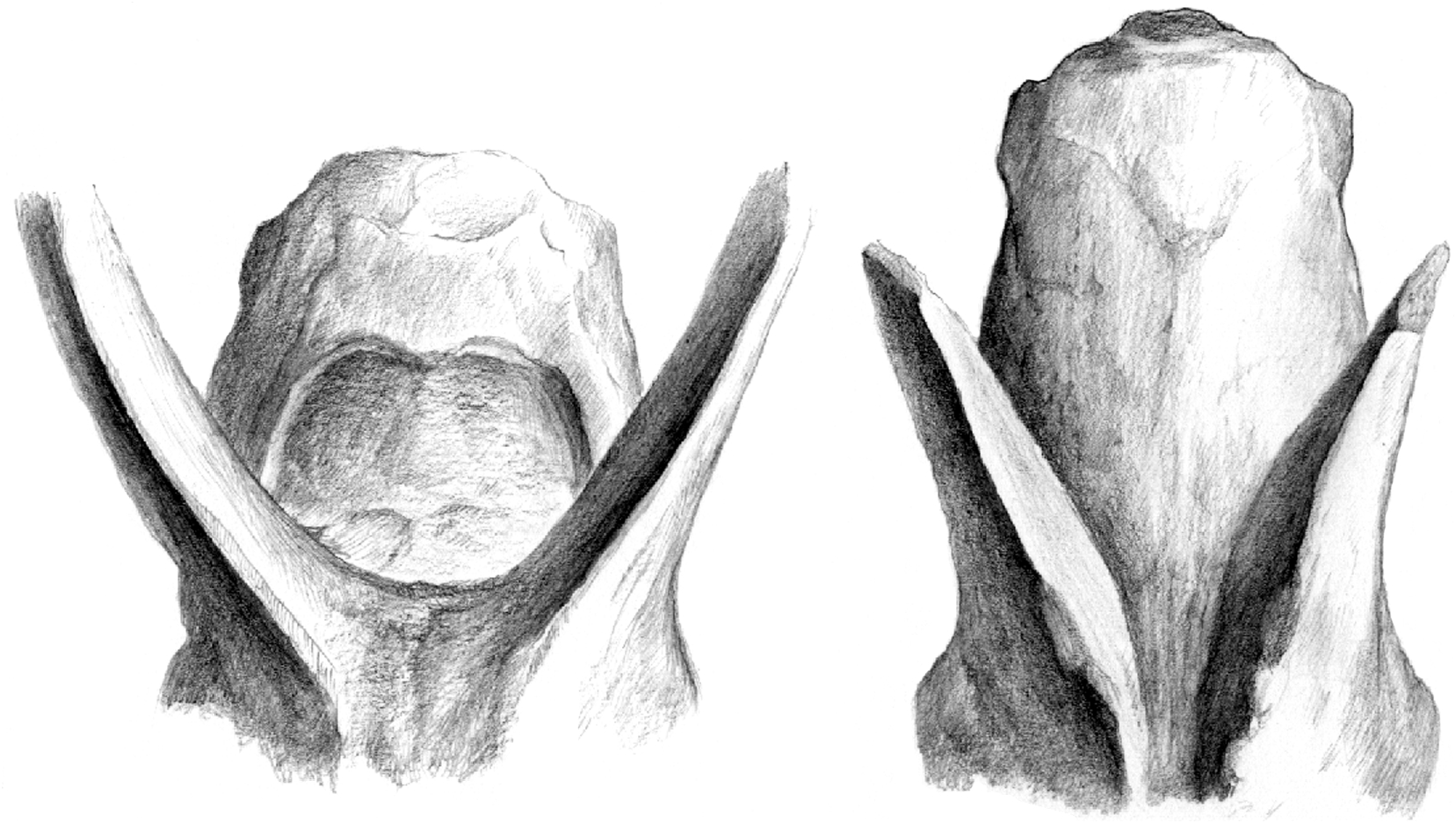

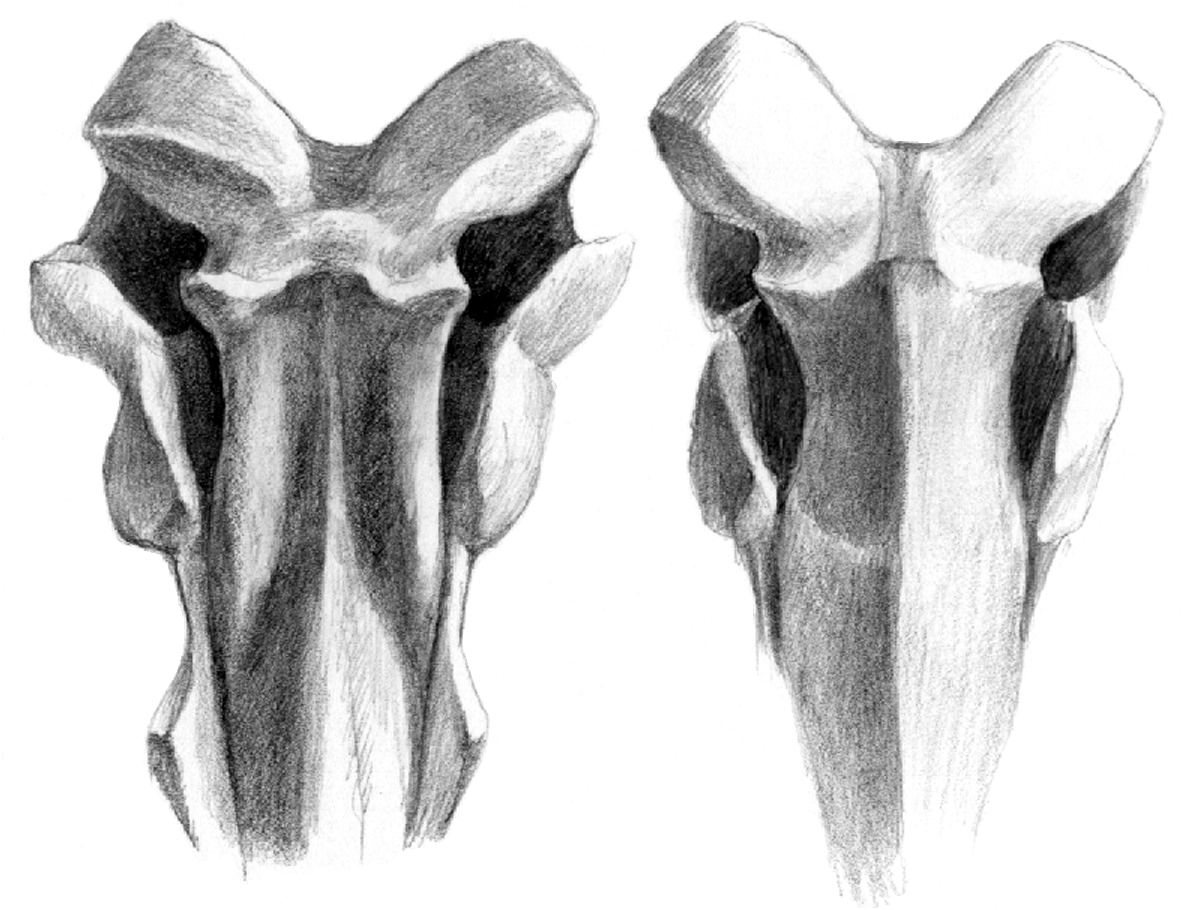

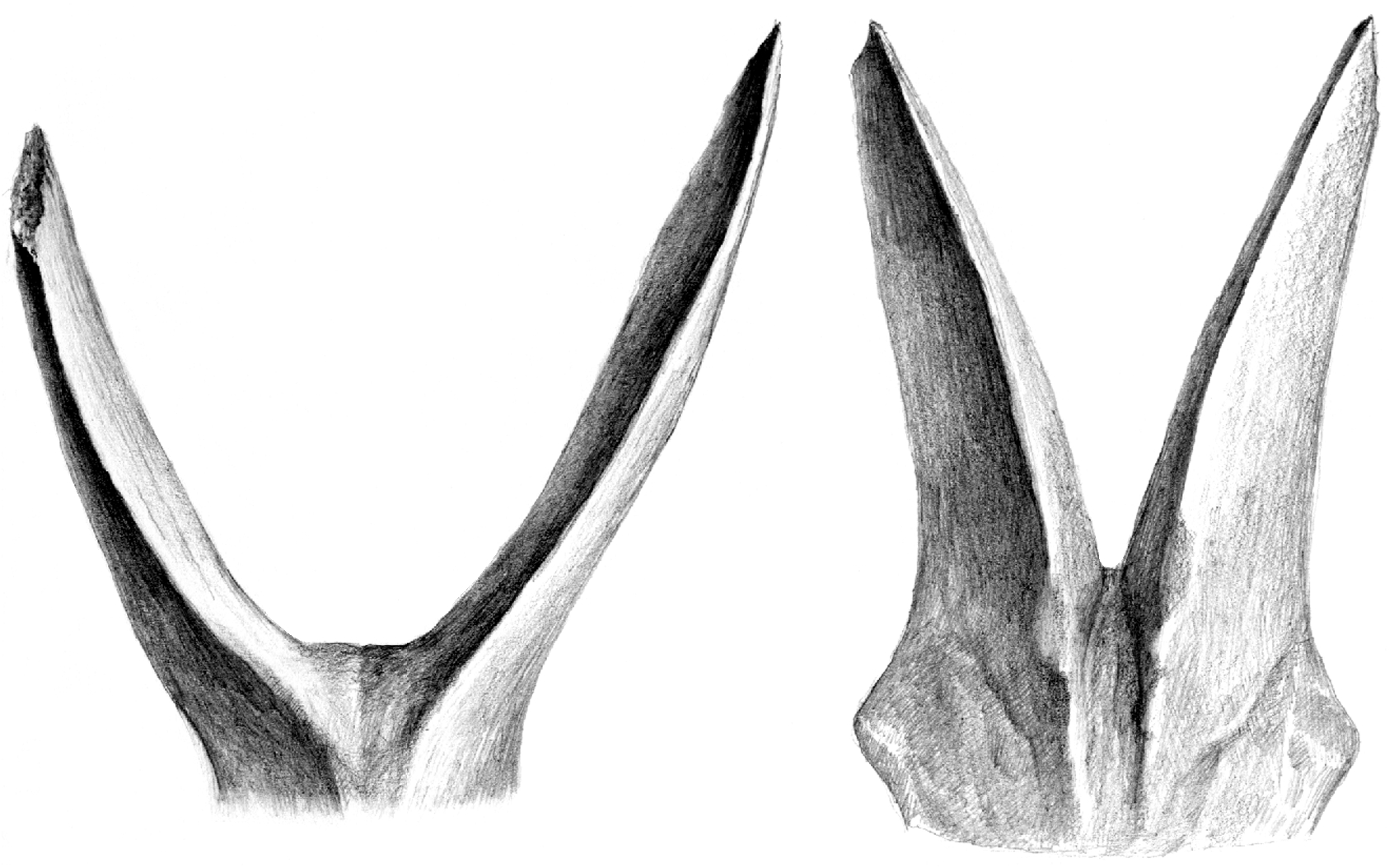

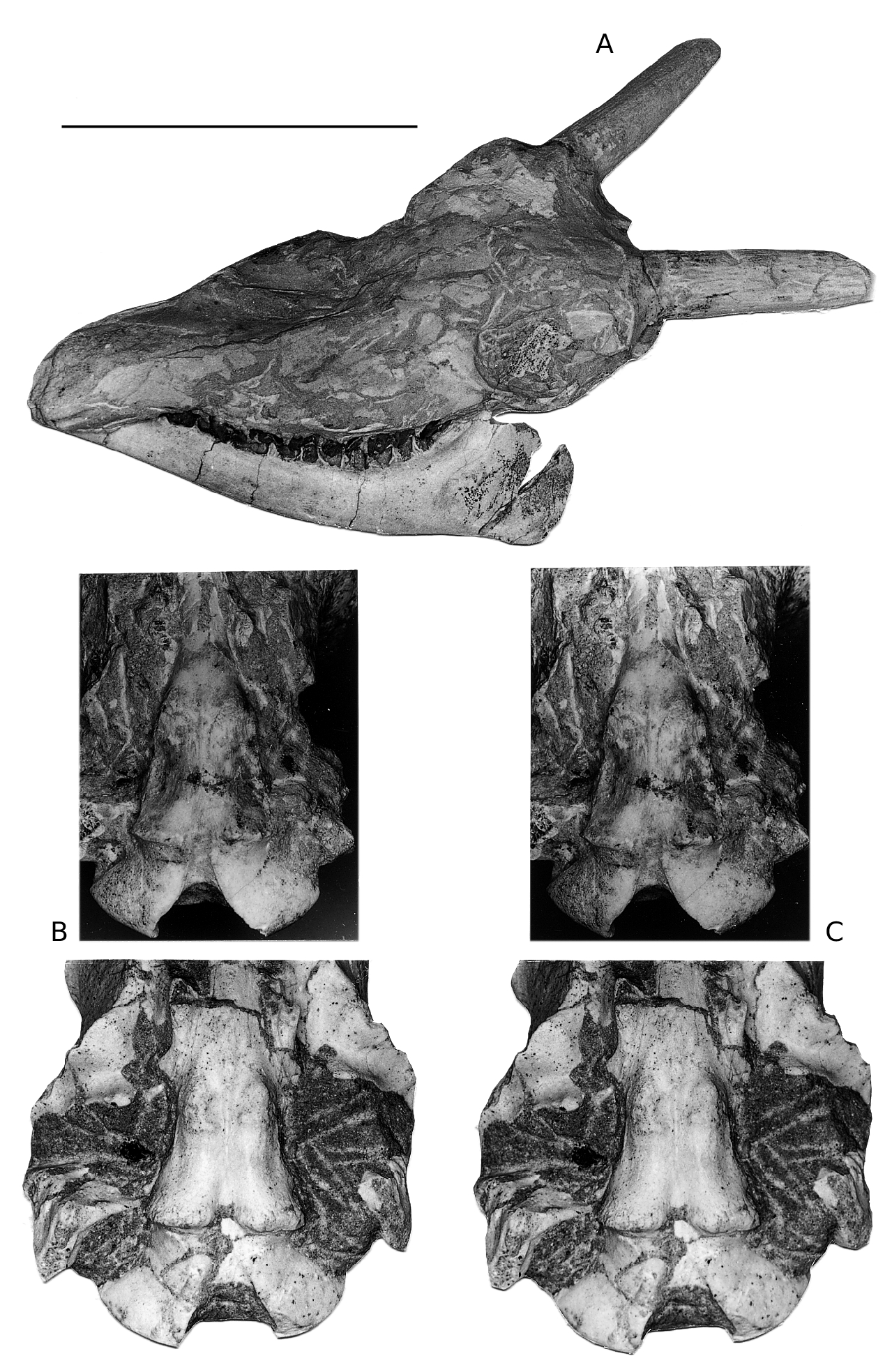

Boselaphini by several features as follows: subtri-? Tragoportax curvicornis Andree, 1926 . Samos angular basal section on the horn-cores related to (= T. browni Pilgrim, 1937 , Siwaliks, Pakistan, Turolian). the presence of distinct anterior and postero- Tragoportax salmontanus Pilgrim, 1937 . Siwaliks external keels; presence of rugosities and crests on ( Pakistan). (About 8.1 to 7.9 Ma, but this absolute the anterior part of the parietals. In fact, only the date is doubtful: Barry et al. 2002). presence of the anterior keel is a constant feature Tragoportax maius Meladze, 1967 . Bazaleti, Georgia (late Turolian). Perhaps a synonym of the poorly for all taxa included in the Boselaphini . The known Tragoportax eldaricus ( Gabashvili, 1956) , type other ones are only strong tendencies that may no species of the genus Mirabilocerus Hadjiev, 1961, from be expressed in some species, or variably the late Vallesian/early Turolian of Eldar in expressed within the same species.? Azerbaijan Tragoportax . cyrenaicus Thomas, 1979 , Sahabi ( Libya), probably late Miocene. Tragoportax acrae ( Gentry, 1974) . Langebaanweg Genus Tragoportax Pilgrim, 1937 ( South Africa), Mio-Pliocene. Tragoportax macedoniensis Bouvrain, 1988 . Dytiko Tragocerus Gaudry, 1861: 298 View in CoL (type species: Capra View in CoL ( Greece; MN13). amalthea Roth & Wagner, 1854 ) (non Tragocerus View in CoL de A number of other specific names, several of them Jean, 1821). from Asia, often based upon fragmentary material, are Tragoportax Pilgrim, 1937: 774 . of doubtful validity; we will mention them in the comparison and discussion but we will not try to revise Pontoportax Kretzoi, 1941: 341 (type species: Trago- them here. cerus parvidens Schlosser, 1904). STRATIGRAPHIC AND GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION. —? Gazelloportax Kretzoi, 1941: 341 (type species: G. gal- From the Vallesian/Turolian boundary (or late licus Kretzoi, 1941). Vallesian?) to the end of the Turolian, perhaps earliest Pliocene in Africa. From southeastern Europe and? Mirabilocerus Hadjiev, 1961: 3 (type species: the northern Paratethys region through Asia minor Tragocerus eldaricus Gabashvili, 1956 ). and the Middle East to Africa and the northern part Tragoceridus Kretzoi, 1968: 165 (type species: Capra View in CoL of the Indian subcontinent (and possibly central amalthea Roth & Wagner, 1854 ). Asia). Mesembriportax Gentry, 1974: 146 (type species: NEW DIAGNOSIS. — Size generally large, approxi- M. acrae Gentry, 1974 ). mately that of European Cervus elaphus View in CoL . The postcornual fronto-parietal surface is a flat or slightly? Mesotragocerus Korotkevich, 1982: 10 (type species: concave well defined depressed area, usually bor- M. citus Korotkevich, 1982 ). dered laterally by well marked temporal ridges and TYPE SPECIES OF TRAGOPORTAX . — Tragoportax caudally by a step leading to a slightly raised plateau salmontanus Pilgrim, 1937 ( Pilgrim 1937: 774) by ( Fig. 1 View FIG ). The basi-occipital has a longitudinal groove original designation. between the anterior and the posterior tuberosities, in the bottom of which often runs a weak sagittal INCLUDED SPECIES. — Tragoportax amalthea (Roth & crest ( Fig. 2 View FIG ). Adult male horn-cores are long and Wagner, 1854). Pikermi, most probably also Samos slender, usually curved backwards, with a triangular and Halmyropotamos ( Greece) (=? T. frolovi to subtriangular cross-section, well marked postero- (M. Pavlow, 1913), Chobruchi [ Moldova]); from the lateral keel and flattened lateral sides, but are less end(?) of the early Turolian to the beginning of the compressed than in Miotragocerus .Anterior rugosilate Turolian. ties growing downwards from the anterior keel at Tragoportax rugosifrons ( Schlosser, 1904) (= T. parvi- the basis of horn-cores are absent or weak, and usudens ( Schlosser, 1904); = T. recticornis ( Andree, 1926) ; ally do not extend onto the frontal. Demarcations = T. punjabicus (Pilgrim, 1910) ; =? T. aiyengari (steps) on the anterior keel are often found, but are (Pilgrim, 1939); =? T. ensicornis (Kretzoi, 1941)) . few when present. Horn-cores have a heteronymous Samos (lower levels?), Prochoma, Ravin des Zouaves, torsion (anti-clockwise on the right horn), so that Vathylakkos-Ravin C ( Greece), Veles-Karaslari the anterior keels first diverge in anterior view, but ( Republic of Macedonia), Hadjidimovo ( Bulgaria), they re-approach towards the tips ( Fig. 3 View FIG ). The Tudorovo ( Moldova)?, Novoukrainka ( Ukraine), intercornual plateau is rather short antero-posteriorly, Siwaliks ( Pakistan) and possibly in Vathylakkos 2 broad and almost rectangular between the horn- ( Greece), Maragha ( Iran) and Kocherinovo-1 cores. The occipital is not much broader ventrally ( Bulgaria), from the Vallesian/Turolian boundary to than dorsally, giving it a trapezoid (rather than trithe middle/late Turolian. angular) outline.

Spassov N. & Geraads D.

Teeth rather hypsodont; labial walls of upper teeth, and lingual ones of lower teeth with less accentuated ribs and styles than in Miotragocerus . Premolars relatively shorter than in Miotragocerus . P2 short relatively to P3, especially its anterior part, and parastyle curved backwards. P3 with lingually inflated hypocone. Metaconid of p3-p4 larger than in Miotragocerus , splayed lingually and T-shaped on p4, with an open anterior valley.

Boselaphini ( Mammalia, Bovidae ) of Bulgaria

Tragoportax rugosifrons ( Schlosser, 1904) HOLOTYPE. — Skull ( Schlosser 1904: pl. 12, fig. 6).

TYPE LOCALITY. — Samos.

NEW DIAGNOSIS. — Tragoportax of large size. The fronto-parietal postcornual depression is as a rule distinctly surrounded by a continuous torus, formed laterally by the temporal ridges and caudally by a transverse ridge connecting the temporal ridges ( Fig. 1 View FIG ). The intercornual plateau is wide. The male horn-cores are usually nearly straight with a moderately convex anterior outline in lateral view, and a slightly concave posterior one. The anterior keel is as a rule regularly curved, with at most a slight tendency to form a demarcation. The tip of the horn-core is not distinct from the general shape and direction of the horn-core (in contrast to T. amalthea ). The anterior keel is almost straight to slightly twisted in front view ( Fig. 3 View FIG ).

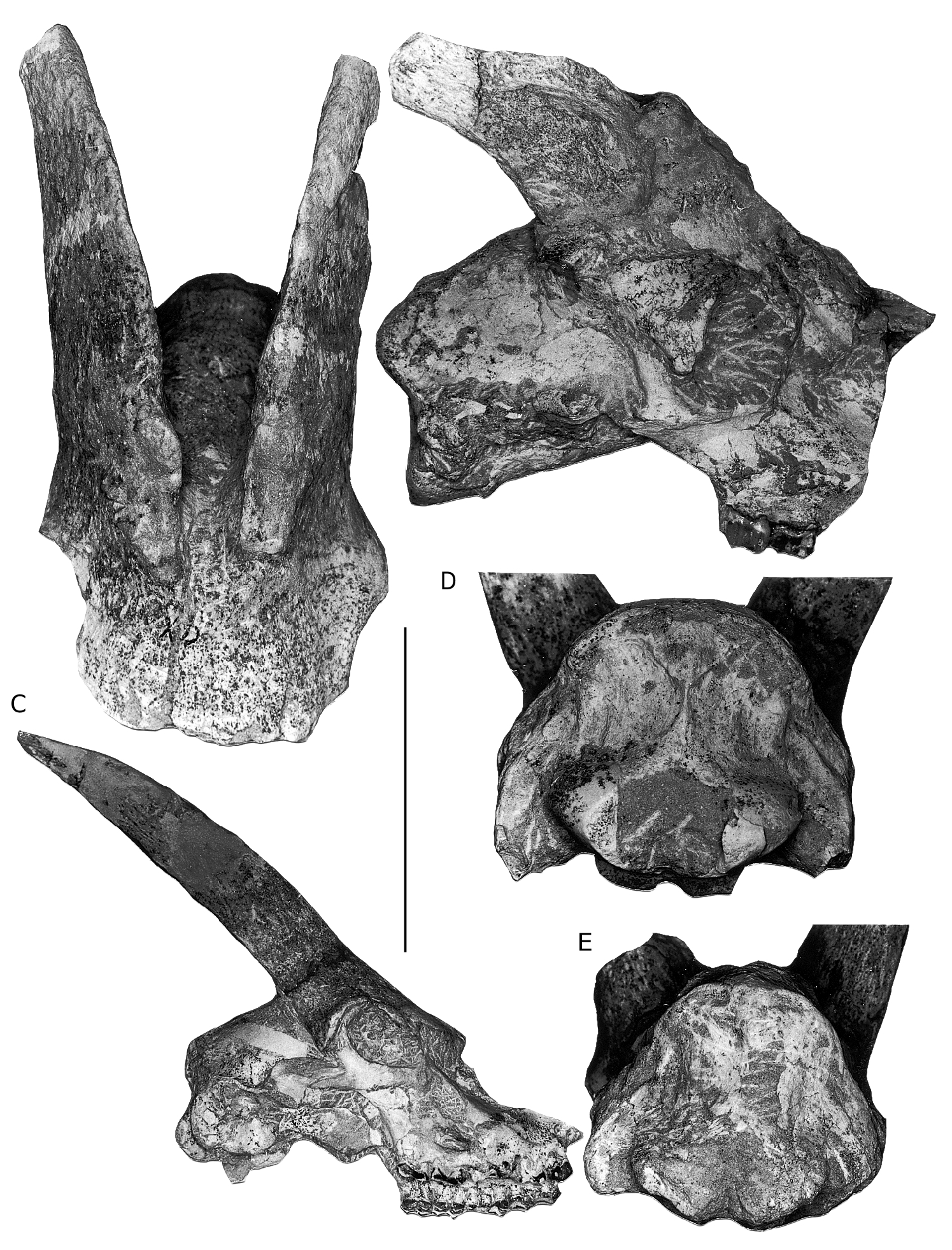

DESCRIPTION OF THE HADJIDIMOVO MATERIAL ( FIGS 4-6 View FIG View FIG View FIG )

The Tragoportax sample from Hadjidimovo is more abundant than that of Miotragocerus and is the third most abundant form of the site, together with Gazella , after Palaeoreas and Hipparion . It is represented mainly by mandibles (159 mandibles and mandibular fragments), more than 40 skulls and skull fragments, upper tooth-rows and a lot of isolated teeth, several tens of metapodials and metapodial fragments (see inventory numbers of the skull, mandibular and metapodial material in Annexe: Tables 1-4, Collection of the Assenovgrad paleontological division of the NMNH).

Skull

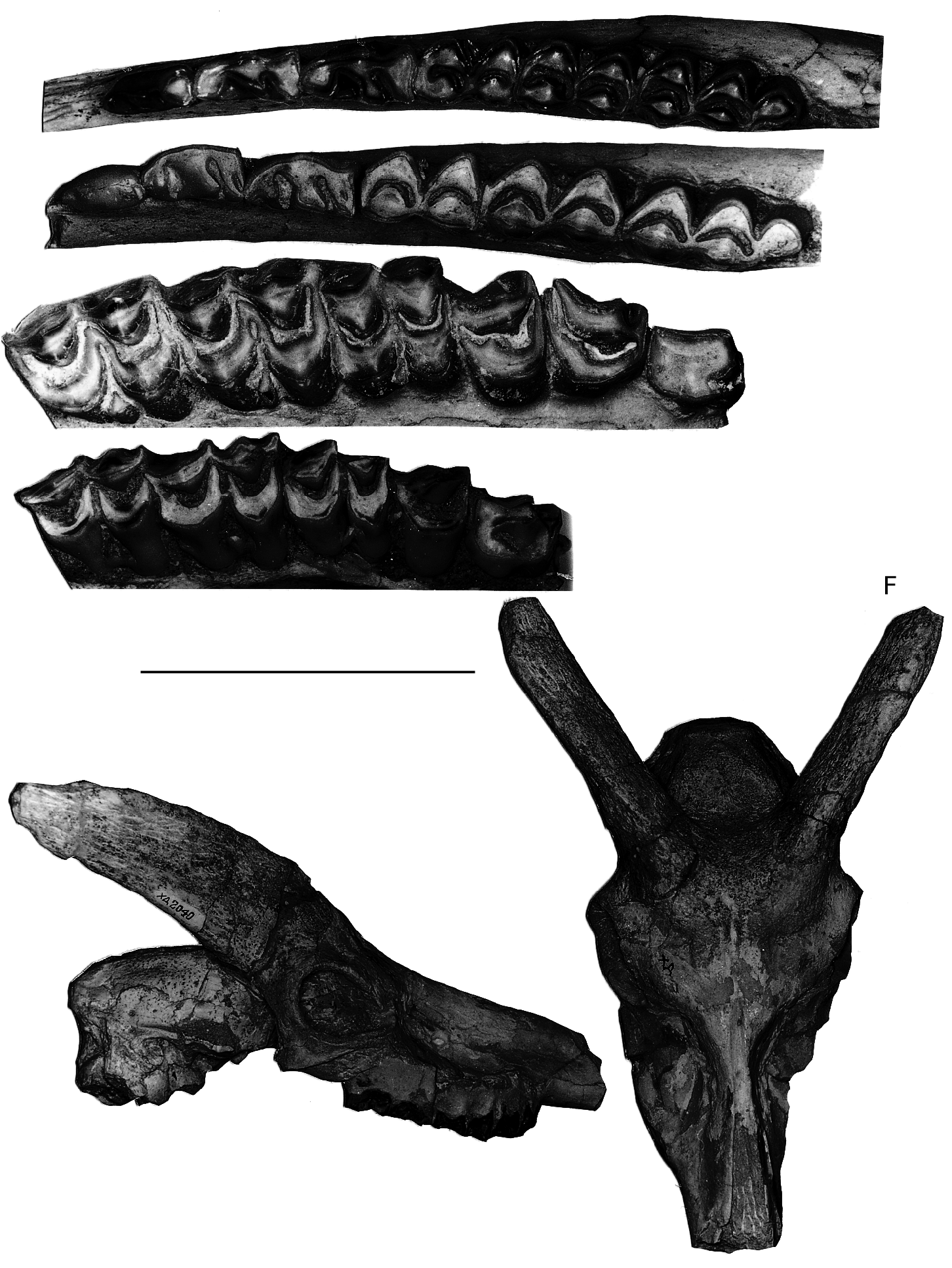

It is larger than that of Miotragocerus (Annexe: Tables 1; 2). There is probably a contact between the premaxilla and the nasal. There is a wide and deep ante-orbital fossa. The infraorbital foramen opens above P2. The anterior border of orbit remains behind the level of M3. The frontals and pedicles are hollowed. The horn-cores are long, and the best preserved skulls suggest that they were inclined backwards. Their antero-posterior diameter is greater than in most other species of the genus. They are usually strongly divergent (about 40- 60°), but the divergence decreases towards the tips. They are but slightly curved backwards, and the posterior border is almost straight. In lateral view, the anterior border forms a regular curve, the tip not being distinct from the base. The anterior keel is not stepped, and continuous. Torsion is always weak, and normal (heteronymous). The basal cross-section in adult males is triangular (Fig. 7), with flattened lateral, medial, and posterior faces. There are usually no posterior grooves. The cross-section is more oval in juveniles, because the postero-lateral keel is less marked, and almost rounded in females (see below). The anterior keel is the strongest; it can bear, especially in old males, rugose bony outgrowths, but they do not normally extend onto the frontal, except in rare exceptions. The intercornual plateau is rectangular, short antero-posteriorly, but wide, the horn-cores being inserted rather far apart, with their medial borders parallel to each other. The fronto-parietal postcornual area is depressed in adult males, often rugose, and surrounded by a strong ridge. The occipital surface is rectangular, its dorsal part being broad. From the occipital foramen to the sphenoid, a continuous groove runs along the basioccipital, often with a weak sagittal keel in its middle. The choanae open well behind M3. The basicranial angle is quite open.

Female and sub-adult skulls

There is no large bovid hornless skull in Hadjidimovo. However, there are at least two skulls that we interpret as females of T. rugosifrons , HD-5130 and 5138 ( Fig. 6A View FIG ). Their teeth are well preserved, and they are both fully adults. Their size (skull and teeth, premolar/molar proportions) and morphology (shape of the frontoparietal area, and basioccipital) are identical to those of the male skulls, and there is no doubt that they belong to the same species. However, their horn-cores are much smaller, with a rounded oval basal cross-section, but with a postero-lateral keel in one of them (HD-5130), without anterior keels or flattening of the surfaces.

We interpret as sub-adult male skulls a few frontlets and brain cases (HD-3034, 2327, 5137, 5140), with horn-cores smaller than in adult males, but with a triangular basal cross-section and flattened surfaces, with well expressed anterior keel.

Teeth

Premolars and molars are large (Annexe: Table 2) and rather hypsodont with relatively less accentuated relief of the walls than in Miotragocerus (Pikermicerus) from the same locality. The premolar row is relatively shorter than in the smaller boselaphine from Hadjidimovo. P2 is short relatively to P3, with a distally sloping parastyle. Its parastyle-paracone portion is short. P3 has a lingually inflated hypocone. The metaconid of p3- p4 is well developed, especially that of p4 which is T-shaped in occlusal view. The anterior valley of p 4 in all observed specimens is open, without the small cuspids that form a kind of cingulum in this region in M. ( Pikermicerus ).

Metapodials

The metapodials are large (Annexe: Tables 3; 4), with a cervid-like appearance, being slender and transversally compressed, but are relatively robust by comparison with the metapodials of the small- er Boselaphini from Hadjidimovo, Miotragocerus . The widening from diaphysis to epiphysis is smooth, without abrupt change of width. The trochlear keels are neither very prominent nor very sharp.

COMPARISONS

There are many differences between the two boselaphines from Hadjidimovo. Tragoportax rugosifrons from this site differs from Miotragocerus of the same locality mainly by: the larger size; the broad rectangular intercornual plateau; the presence of a fronto-parietal postcornual depression; the shape of the basioccipital (with longitudinal groove often with a thin sagittal crest); the long horn-cores with a relatively small antero-posterior diameter, compared to the length; their triangular cross-section and normal torsion; the hypsodont teeth; the relative length and morphology of the premolars ( Figs 1-11 View FIG View FIG View FIG View FIG View FIG View FIG ; Annexe: Tables 1-4).

The Tragoportax from Hadjidimovo has similarities with T. amalthea in its main features and general aspect, but also differs clearly by: the greater intercornual distance, the less robust horn-cores ( Figs 12 View FIG ; 13 View FIG ), lesser development of

A

B

C

D

E A B

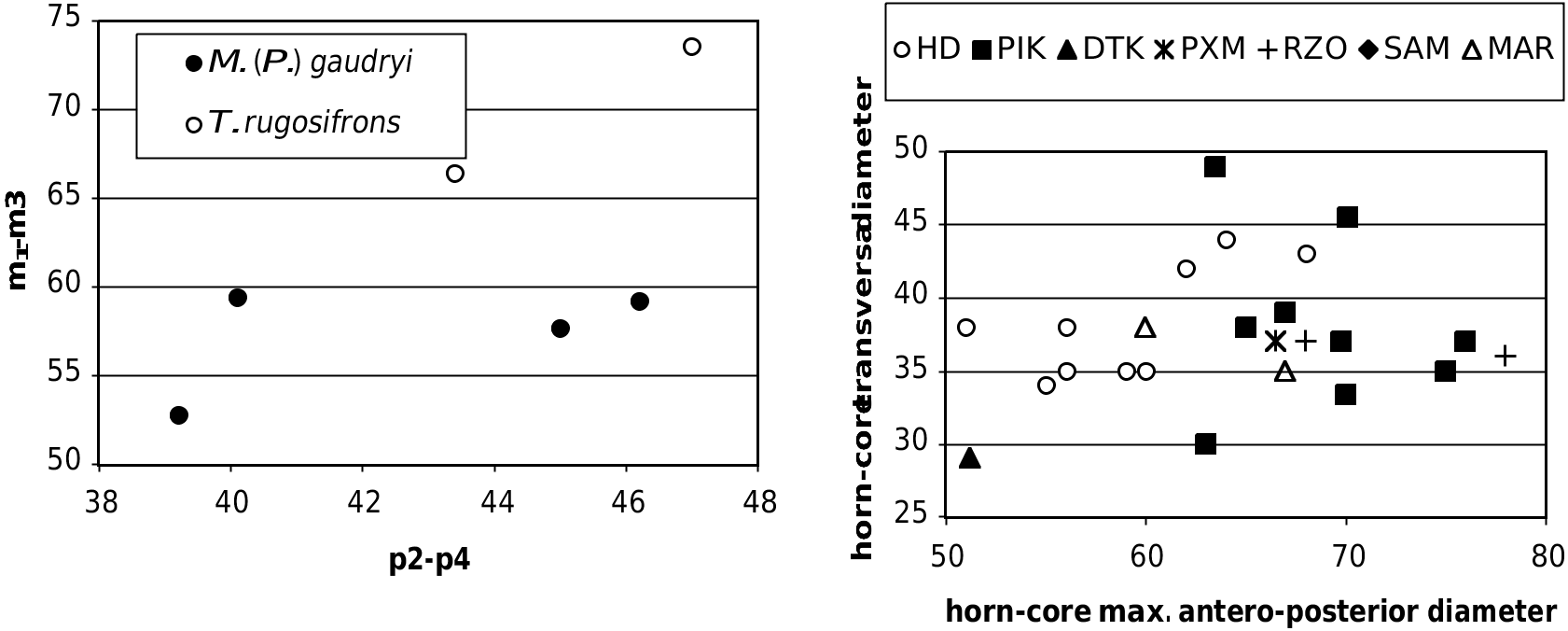

the rugosities on the anterior horn-core keel, less- er concavity of the caudal face of the horn-core in lateral view, usually weaker torsion of the horncore anterior keel, as well as by the virtual lack of steps (demarcations) on the keel. The tip of the horn-core is usually not distinct from the general outline of the horn-core, or at least less so than in the Pikermi T. amalthea , where this tip is demarcated by a marked concavity of the anterior edge in lateral view. The cheek-teeth sample from Hadjidimovo shows also some differences, having somewhat shorter premolar row in relation of the molars (Fig. 14).

From the specimens described as T. curvicornis ( Andree 1926: pl. 12, figs 6, 7; Solounias 1981: fig. 30-H), the sample from Hadjidimovo differs by the very slight backward curve of the horncore (reflected in the very slight concavity of the posterior border of the horn-core in lateral view). “ Miotragocerus ” cyrenaicus Thomas, 1979 from Sahabi ( Libya) differs by its curved and divergent horn-cores, but the species is illustrated by a single specimen. Should this difference be constant, it could be a valid species, otherwise, it could be closely related to T. curvicornis .

The single specimen from Novaya Emetovka (type of Mesotragocerus citus Korotkevich, 1982 ) that could be referred to Tragoportax shows more twisted and more inclined horn-cores than the Hadjidimovo form.

From T. (“ Mirabilocerus ”) maius Meladze , of which we have seen good photos kindly provided by A. Vekua and D. Lordkipanidze (see also Meladze 1967: pl. 27), the sample from Hadjidimovo differs by the larger and more quadrangular intercornual surface, the much stronger temporal lines and torus that surrounds the fronto-parietal postcornual depression. The horncores are less inclined and have a totally different profile, with the antero-posterior diameter decreasing gradually, in contrast of the abrupt diminishing in “ Mirabilocerus maius ” above the first half of the horn-core, with a change of curve in its second half, thus forming a sinusoidal contour. “ M. ” maius is perhaps a junior synonym of T. (“ Mirabilocerus ”) eldaricus ( Gabashvili, 1956) , the type of which is an isolated horn-core.

The horn-cores of the specimens from Hadjidimovo differ by the same features from those of T. acrae ( Gentry 1974, 1980). The latter differ also by their convex posterior profile (instead of concave in the Hadjidimovo sample).

The Tragoportax from Hadjidimovo is much larger than T. macedoniensis (Bouvrain, 1988) , and has straighter and more robust horns in males, more rectangular intercornual surface and more rectangular (wider) occipital surface.

Compared with T. salmontanus from Siwaliks (type species of the genus) the horns of the Hadjidimovo Tragoportax are longer, less inclined and not so twisted. There are less rugosities on the fronto-parietal postcornual surface (see Pilgrim 1937, 1939). The horncores of the poorly known T. perimensis from the Middle Siwaliks (Pilgrim 1939) are much shorter. Another poorly known species from Siwaliks, T. islami (a possible synonym of T. salmontanus ), has also more rugosities on the fronto-parietal postcornual surface, which extends farther back than in the Hadjidimovo form.

The sample of Tragoportax skulls from Hadjidimovo shows all the main features of the Tragoportax rugosifrons morphology, by comparison with the type specimen and the other Samos specimens figured and described by Schlosser (1904). Two undescribed Tragoportax adult male skulls in the National Museum of Natural History, Skopje ( Republic of Macedonia) from Veles-Karaslari have large dimensions and horn-cores that are strongly divergent at the base, almost straight, with very weak torsion, and with continuous (not stepped) anterior keel, without marked rugosities. These skulls are identical with the skulls from Hadjidimovo and represent the same species. The skulls from Hadjidimovo are similar to the preserved skulls with horn-cores of T. rugosifrons from Prochoma. The skull PXM- 17 ( Bouvrain 1994) has smaller intercornual distance due to a lateral compression and deformation of the skull. The specimen PXM-93 has horn-cores curved backward, but this is probably due to individual variability.

DISCUSSION Pikermicerus

The first described and best known species of

Tragoportax is T. amalthea (Roth & Wagner,

1854). It is a large form which has relatively twisted and very robust horn-cores, with a tendency to clear demarcations on the anterior keel and with the tip of the horn-core well distinct from the general shape and direction of the horncore. The type locality is Pikermi but some skulls very similar to the Pikermi sample have been found in Samos as well (see Andree 1926: pl. 10,

figs 4-6, 8; Solounias 1981: fig. 28a-c) and probably represent a Samos subspecies of T. amalthea ,

seemingly characterized by longer and more slen-

der horns. Specimens with similar horn-cores are also known from Halmyropotamos, Greece

(Melentis 1967) and Chobruchi, Moldova

(Korotkevich 1988).

Tragoportax rugosifrons ( Schlosser, 1904) is probably the most widespread species (in number of localities and possibly in chronological longevity as well). It is also (together with T.? eldaricus )

among the earliest species.The horn-cores of

T. rugosifrons are nearly straight. The anterior keel is without or with a slight torsion (i.e. spiral)

as well as almost without flat steps (demarcations), forming a continuous curve from base to tip. This horn structure is characteristic for most specimens of Schlosser’s collection from Samos,

for Hadjidimovo, for the adult and subadult HD-5133 HD-2040

male skulls from Veles-Karaslari and for several samples from Greece (see above) as well as for the FMiotragocerus IG. 7. — Horn-core from Hadjidimovo cross-section, all shown in Tragoportax as if from the right and specimens referred to T. frolovi by Korotkevich side (HD-5133 inverted). The front side is towards the top of the (1988) from Novoukrainka from the Black Sea page, the lateral side to the right.

region. The specimens from Samos described as

T. recticornis ( Andree, 1926) have the same horncore morphology. The material, also from Tragoportax cf. rugosifrons is represented in Samos, described and figured by Schlosser (1904) Maragha, Iran, by some tooth-rows and a skull as “ Tragocerus amalthea var. parvidens ” is seem- with horn-core (MNHNP MAR 1395; ingly identical with T. rugosifrons . The skull Mecquenem 1924: pl. 6, fig. 3). The skull shows described by Pilgrim (1910) from the Siwalik as the Tragoportax postcornual and basioccipital “ Tragocerus punjabicus ” shares the same horn- features and general horn-core shape close to core morphology as well, and could also be T. rugosifrons . The preserved horn-core is also referred to T. rugosifrons . The skull from strongly curved backward, as in the Prochoma Prochoma (PXM-93) ( Bouvrain 1994) with specimen.

horn-cores relatively strongly curved backwards is Tragoportax curvicornis ( Andree, 1926) from rather atypical for the species (see above). Samos is, according to several contemporary

75 300

285

width

70 270

65 255

condylar 60 length 240 225

bi 55 210

195

50 180

80 85 90 95 100 105 110 115

165

maximum occipital width 150

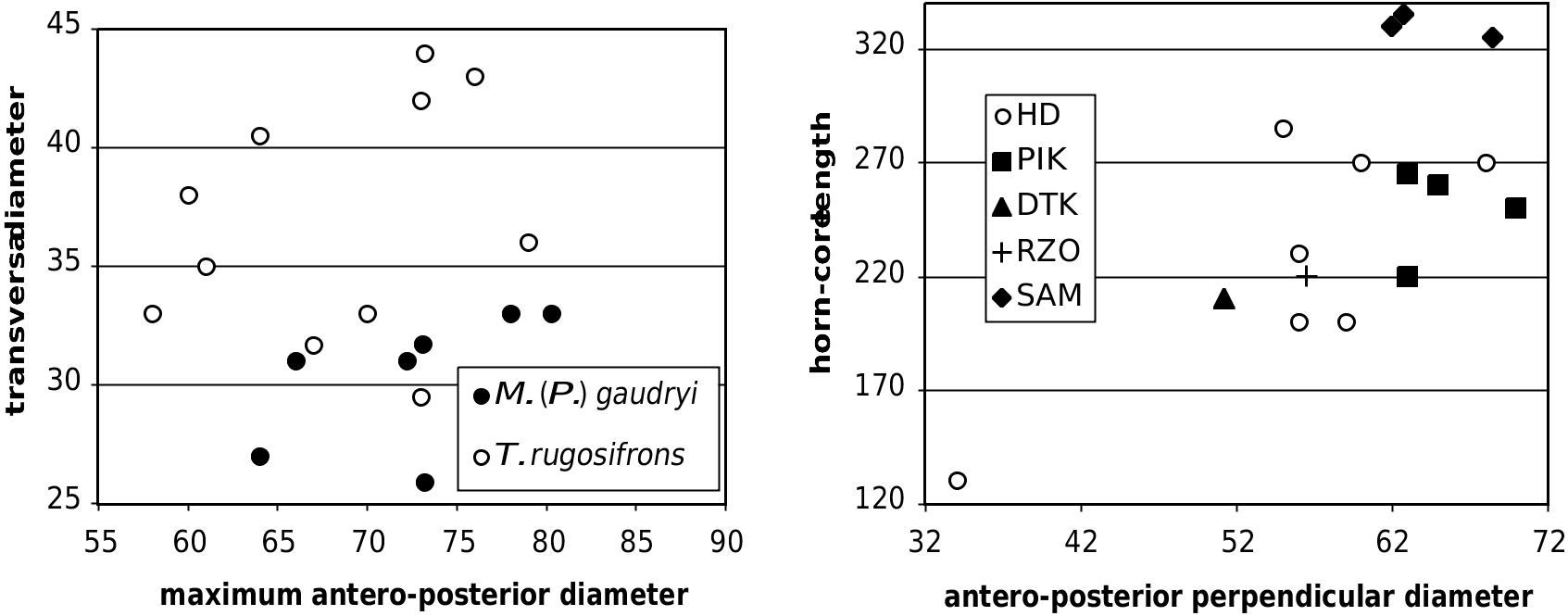

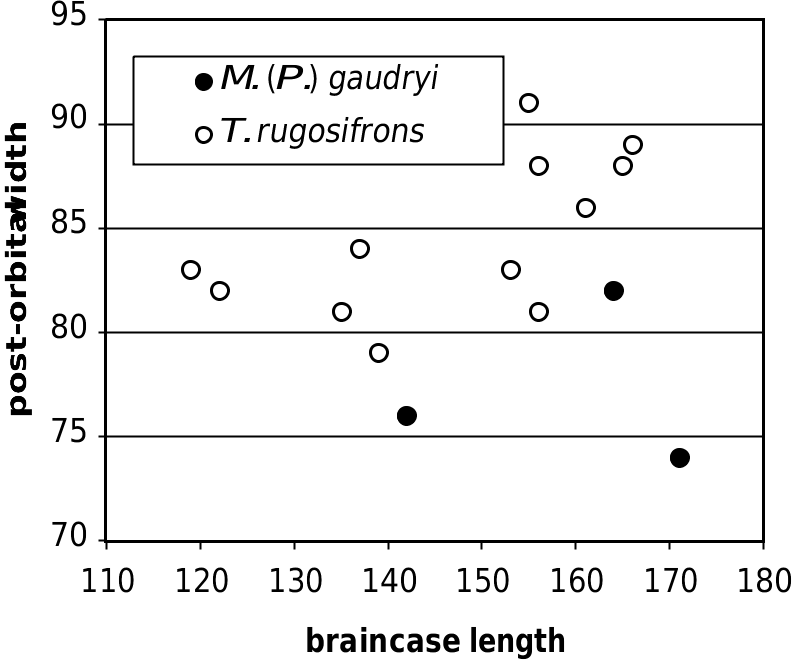

55 60 65 70 75 80 FIG. 8. — Neurocranial dimensions, in mm, in Tragoportax rugosifrons ( Schlosser, 1904) and Miotragocerus (Pikermicerus) maximum antero-posterior diameter gaudryi (Kretzoi, 1941) from Hadjidimovo.

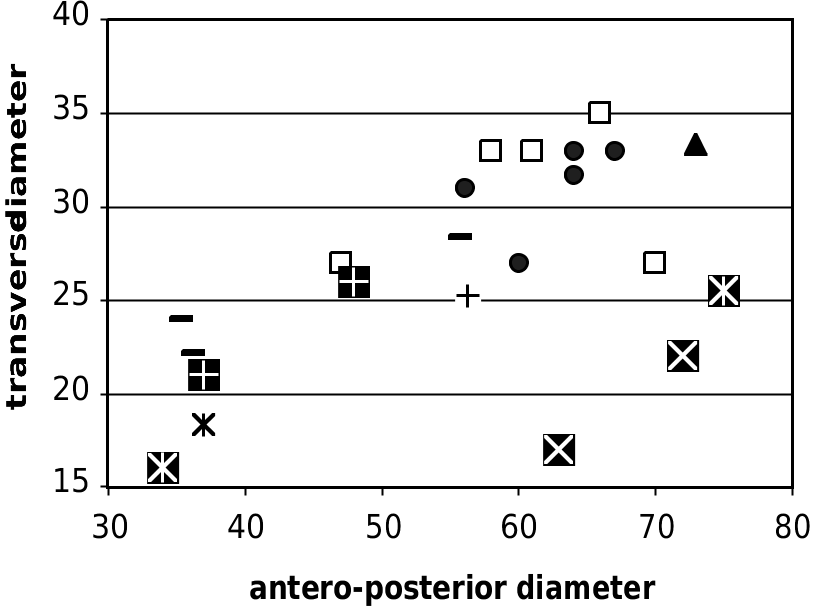

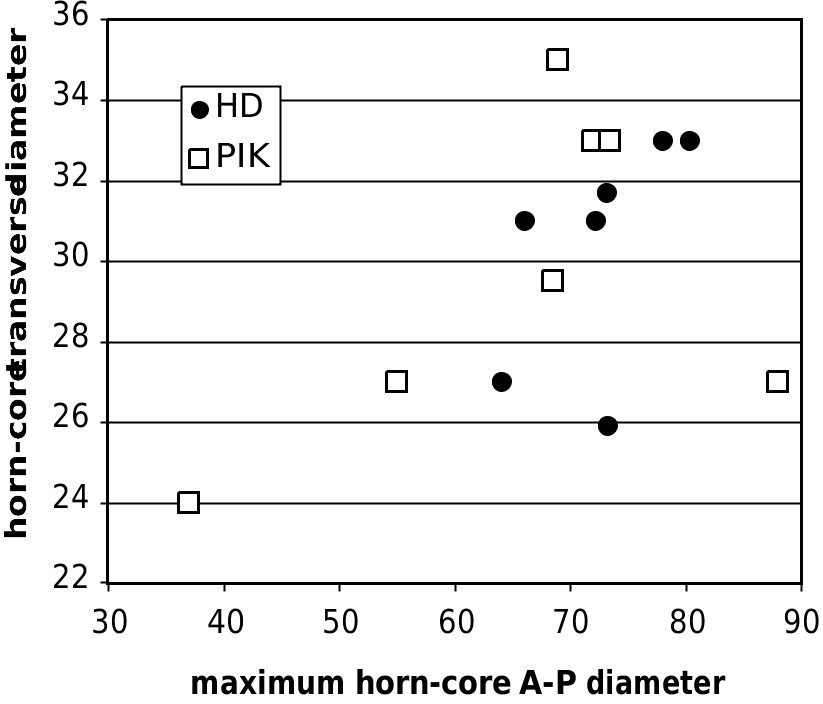

FIG. 9. — Horn-core proportions and length, in mm, in

Tragoportax rugosifrons ( Schlosser, 1904) and Miotragocerus authors, a junior synonym of T. rugosifrons (or of (Pikermicerus) gaudryi (Kretzoi, 1941) from Hadjidimovo.

“ T. punjabicus ”) (Moyá-Solá 1983; Bouvrain &

Bonis 1983; Bouvrain 1988). Given the scarcity of the material of T. rugosifrons -T. “ recticornis ”- skull of “ M. ” brevicornis Meladze, 1967, of which T. “ curvicornis ” from Samos, this conclusion is we have seen unpublished photos, has a basiocquite logical, but not mandatory as, e.g., the vari- cipital without longitudinal groove, narrow interous levels of Samos could yield different forms. cornual surface and rather rounded anterior horn Judging from the limited variability of the horn surface different from Tragoportax and seems to morphology in the other T. rugosifrons samples be a separate form.

(Hadjidimovo, Tudorovo, Veles-Karaslari, etc.) The geographic remoteness and late geological we doubt that the strong curves of the horn-cores age of Mesembriportax acrae Gentry, 1974 from of the two specimens noted as T. curvicornis the early Pliocene of South Africa would suggest ( Andree 1926: pl. 11, fig. 6; Solounias 1981: generic distinction from Tragoportax , but it disfig.30C, H) could be included within the varia-plays all the main cranial features of Tragoportax tion range of T. rugosifrons , and we prefer to keep ( Thomas 1979; and figures in Gentry 1974, T. curvicornis as a valid name. The horn-cores of 1980) and for the moment this generic distinc- T. browni Pilgrim, 1910 from the Siwaliks are tion is not well supported.

similar in shape to T. curvicornis and both species “ Tragoceras leskewitschi ” Borissiak, 1914 from the could be identical. We are unable to take a deci- late Vallesian of Sebastopol-1, regarded in several sion on the taxonomic status of “ Mirabilocerus ” recent works as a Tragoportax species (Moyá-Solá without direct observation of the Bazaleti, Eldar 1983; Bouvrain 1988; Kostopoulos & Koufos and Arkneti material included in this taxon by 1996), must be excluded (as supposed by Meladze (1967). From the descriptions (Meladze Bouvrain 1994) from this genus. The temporal 1967) and photos, one may suppose that the crests are strong as in Tragoportax , bordering materials from Bazaleti – and perhaps from Eldar some kind of postcornual plateau (but not a – represent Tragoportax . The profile of the horn- depression?), but the basioccipital and the narcores and the correlated triangular intercornual row, triangular occipital surface of the skull are surface are similar to those of Miotragocerus , but mostly Miotragocerus -like. The horn-cores are not the basioccipital and the postcornual morphology strongly flattened on the lateral and medial sides, (preserved only in “ M. ” maius from Bazaleti) dis- in contrast to Tragoportax and Miotragocerus , and play the features of Tragoportax . The Arkneti have more rounded anterior keels and small antero-posterior diameter. Korotkevich (1988) refers this species to Protragocerus , and this is one of the possible identifications (but see also below the General discussion).

The form from Kazakhstan described as Tragocerus irtyshense (Musakulova-Abdrahmanova 1974) has a very broad intercornual surface, and oval section of the horn-cores. It does not display Tragoportax features either.

The genus Tragoportax has been reported from the Turolian of Kalimantsi ( Bulgaria), by Bakalov &

Nikolov (1962). An unpublished skull fragment from this locality could belong to T. rugosifrons or to T. amalthea . It is represented in Nikiti-2, Greece (Kostopoulos & Koufos 1999). In both localities it co-exists with Miotragocerus (Pikermicerus) (see below), but the specific status of the Tragoportax specimens is unclear.Such a coexistence is likely in Maramena (end of MN13) as well (see Köhler et al. 1995).

74 primitive by its straight slender horn-cores, that are inserted widely apart, with an incipient trian- 72

gular cross-section, and by the longitudinal 70 groove on the basi-occipital restricted to the pos- 3

m

terior part.

- 68

1 m The large Mesotragocerus citus Korotkevich, 1981 66 (Korotkevich 1988; Krakhmalnaya 1996) from the Turolian of Novaya Emetovka ( Ukraine) 64

should be referred to Tragoportax (even if it is not 62 sure that T. citus is a bona fide species). The pho- 40 42 44 46 48 50 tos kindly sent us by Y. Semenov (National p2-p4 Museum of Natural History, Kiev) display the typical features of Tragoportax on the basioccipi- FIG. 14. — Mandibular tooth proportions and size, in mm, in tal and on the postcornual fronto-parietal surface. Tragoportax from various localities. Abbreviations:

HD, Hadjidimovo; MAR, Maragha; SLQ, “Thessaloniki”,

Arambourg’s collection; PIK, Pikermi; NIK, Tragoportax sp. ,

Nikiti-2.

Genus Miotragocerus Stromer, 1928 Miotragocerus Stromer, 1928: 36 .

Most of the Tragoportax species from the Dhok

Pathan and Nagri formations of the Siwaliks Pikermicerus Kretzoi, 1941: 342 (type species: ( Thomas 1984; Bouvrain 1994) were described on P. gaudryi Kretzoi, 1941 ).

fragmentary material ( Lydekker 1878; Pilgrim? Indotragus Kretzoi, 1941: 342 (type species: I. pilgri- 1939). Some of them (see above) could be mi Kretzoi, 1941).

synonymized with forms known from Europe. Dystychoceras Kretzoi, 1941: 336 (type species: D. pan- The taxonomic status of the T. perimensis - noniae Kretzoi, 1941).

T. salmontanus - T. aiyengari - T. islami group is un- TYPE SPECIES OF MIOTRAGOCERUS . — Miotragocerus clear ( Thomas 1979; Moyá-Solá 1983; Bouvrain monacensis Stromer, 1928 ( Stromer 1928: 36) by orig- 1994). T. salmontanus could well be a distinct inal designation.

species. Photos of the type (kindly sent to us by INCLUDED SUB- GENERA. — Miotragocerus (Miotra- E.Delson, American Museum of Natural History, gocerus) Stromer, 1928; Miotragocerus (Pikermicerus) New York) show a well expressed fronto-parietal Kretzoi, 1941.

postcornual depression with strong rugosities and INCLUDED SPECIES. — Miotragocerus (Miotragocerus) a groove on the preserved part of the basioccipital. monacensis Stromer, 1928 . Oberföhring ( Germany); Hostalets?, Ballestar? ( Spain); c. MN8/9.

The skull is characterized by short and robust,? Miotragocerus (Miotragocerus) pannoniae Kretzoi , twisted and inclined horns as well as by the skull 1941. Sopron ( Hungary); Altmannsdorf, Mistelbach, dome relief: strong postcornual torus with V- Inzersdorf ( Austria); most possibly also Eppelsheim shaped caudal part and a well marked connection and Höwenegg ( Germany). The species has also been listed in several localities from the Vallesian of Spain of the temporal ridges behind it. The holotypes of ( Morales et al. 1999), from Kalfa in Moldavia T. islami Pilgrim, 1939 and T. aiyengari Pilgrim , (P e v z n e r & V a n g e n g e i m 1 9 9 3) a n d G r i z e v i n 1939 must be referred to Tragoportax . T. aiyengari Ukraine (Korotkevich 1988); late middle Miocenehas some similarities with T. rugosifrons and could Vallesian.

Miotragocerus (Pikermicerus) gaudryi (Kretzoi, 1941) be a synonym. T. islami shows particularities in with probably four subspecies (see below). Mostly at: the postcornual surface morphology very similar Pikermi, Samos, Halmyropotamos ( Greece, Turolian); to the skull dome relief of T. salmontanus and Hadjidimovo ( Bulgaria, early/middle Turolian), probably is a synonym of the latter. dle Veles-Karaslari Turolian), (Republic Le Coiron of, Macedonia Ardèche ( France, early or, early mid-

Sivaceros Pilgrim, 1937 , from the Chinji stage of Turolian); probably also at Belka ( Ukraine, Turolian); the Siwaliks, recalls Tragoportax , but is more Piera, early Turolian and Venta del Moro, late

Turolian ( Spain); mont Lubéron ( France, middle/late the size of the fallow deer, without lateral and medial Turolian); Maragha ( Iran,?early Turolian); Nikiti-2 longitudinal groves (depressions); abrupt widening ( Greece, early Turolian) and Maramena ( Greece, from diaphysis to epiphysis. Turolian/Ruscinian boundary). The presence of the species at Nikiti-1 ( Greece,?end of the Vallesian) is STRATIGRAPHIC AND GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION. — uncertain. Whole Turolian; possibly late Vallesian.Europe and Possibly also a fourth species: see “ Tragoportax perhaps Middle East (see above the distribution of the (Pikermicerus) aff. gaudryi ”: Moyá-Solá 1983 (see genus). Discussion). Spain, France, late Vallesian. STRATIGRAPHIC AND GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION. — From MN8/9 to the end of MN13 of Europe and pos- Miotragocerus (Pikermicerus) gaudryi sibly the Middle East. (Kretzoi, 1941) NEW DIAGNOSIS.— (The shape of horn-cores and Pikermicerus gaudryi Kretzoi, 1941: 342 . those of associated structures are those of adult Miotragocerus monacensis – Solounias 1981 (pars): 102. males). Size small (about that of fallow deer). The postcornual area of the skull is not depressed or raised Tragoportax gaudryi – Moyá-Solá 1983: 124. as a low plateau ( Fig. 1 View FIG ). Basioccipital, definitely known in the subgenus Pikermicerus , without median HOLOTYPE.— Skull illustrated in Gaudry (1865: longitudinal groove between the anterior and the pos- pl.49, fig. 1). terior tuberosities, but with a faint sagittal keel TYPE LOCALITY. — Pikermi. ( Fig.2 View FIG ). Strong temporal crests (at least in males) in early forms ( Miotragocerus ), weaker in more recent DIAGNOSIS.— That of the subgenus. ones ( Pikermicerus ). Horn-cores moderately long to long in early forms and short in later ones, mediolaterally compressed, with flattened lateral and medial M. (Pikermicerus) gaudryi gaudryi surfaces. Sharp anterior keel, but postero-lateral keel (Kretzoi, 1941) absent or poorly marked, and posterior face not well delimited. The section is therefore sub-elliptic HOLOTYPE.— Skull illustrated in Gaudry (1865: (Fig.7). Anterior rugosities at base of horn-cores usu-pl.49, fig. 1). ally strong, extending onto the frontal along the keel, which often has several demarcations (steps) along its TYPE LOCALITY. — Pikermi. course. In front view, due to a slight torsion of the DIAGNOSIS.— A subspecies of M. (P.) gaudryi with horn-cores bases, the keels are often slightly conver- horn-cores straighter than in M. (P.) gaudryi andangent upwards in the basal portion, then diverge censis from the early Turolian of France, larger than towards the tips ( Fig. 3 View FIG ). The intercornual area is M. (P.) gaudryi crusafonti from the early Turolian of much longer than broad, especially narrow anteriorly. Spain and France, teeth smaller than those of M. (P.) The occipital surface is high, much broader basally gaudryi leberonensis from the late Turolian of the same than at its top. Teeth brachyodont, with strongly area. folded walls. Compared to Tragoportax , well documented forms have a long premolar row, with especially long P2 compared to P3, due to lengthening of its anterior part. Hypocone of P3 poorly expanded DESCRIPTION OF THE HADJIDIMOVO MATERIAL lingually. Metaconid of p3-p4 weak, anterior valley ( FIGS 4-6 View FIG View FIG View FIG ) with incipient lingual wall. (Coll. of the Assenovgrad paleontological division of the NMNH): complete and partial skulls

(HD-2007, 2010, 2015-2016, 2019, 2039,

Subgenus Miotragocerus (Pikermicerus) 2325 , 3704, 5519); several identified mandibles

Kretzoi, 1941 and metapodials (see inventory numbers in TYPE SPECIES. — Pikermicerus gaudryi Kretzoi, 1941 : Annexe: Tables 2-4). 342. The subgenus is, in our conception, monospecific, with a possible second species from the late Skull Vallesian of Western Europe. It is larger than those of M. monacensis , but DIAGNOSIS. — Cranial features to M. as Miotragocerus for genus. Weak smaller than those of Tragoportax from Hadtemporal lines. Compared (), the horn-cores are relatively short and massive, with a con- jidimovo (Fig. 8). The ante-orbital fossa is small cave caudal edge. Long premolar row. Metapodials of and shallow. The anterior border of orbit does not reach the level of M3 (one specimen observed). The frontals, and probably also the pedicles, are hollowed. The horn-cores are short, slightly inclined backwards, and very compressed transversally. They look stout and massive in lateral view: their antero-posterior diameter is greater than in other species of the genus (Figs 9; 15) and this dimension is greater relatively to the length of the horn-core than in Tragoportax from the same locality. Horn-cores are only slightly divergent. In lateral view the anterior contour is strongly curved, but the posterior one is only slightly curved backwards. The demarcations are well represented along the anterior keel. The keel torsion is weak (in some specimens almost absent) and homonymous: in front view the keels are often slightly convergent upwards at base, then diverge towards the tips. The basal crosssection in adult specimens of both sexes is subtriangular, less triangular than in Tragoportax from the same locality, with a rounded posterior face (Fig. 7), without longitudinal groove, nor postero-lateral keel (only very weakly distinct in a few specimens). The anterior keel between the demarcations is well marked. The rugosities on the anterior keel are more common than in Tragoportax from the same locality and in most cases they extend onto the frontal. The intercornual plateau is usually long, narrow and triangular. The neurocranium is proportionally long and narrow compared to Tragoportax ( Fig. 16 View FIG ). The fronto-parietal postcornual area is not depressed, and shows rugosities in one specimen. The occipital surface is subtriangular, its dorsal part being relatively narrow with bulging top. The basioccipital has no median longitudinal groove, but bears a faint sagittal keel ( Fig. 2 View FIG ). The basicranial angle (one specimen observed) is quite well marked (but less than in Palaeoreas ).

Teeth

Premolars and molars are relatively small and brachyodont with pronounced relief of the labial walls of upper teeth. The premolar row is relatively longer than in Tragoportax . P2 is long relatively to P3, due to lengthening of its anterior part. Its parastyle is straight, not curved distally. P3 has a narrow parastyle, not protruding labially. The metaconid of p3-p4 is weak, the anterior valley has an incipient lingual wall. Length M1- M3 (53.0 mm) falls within the size range of Pikermi (48.6-53.9 mm), it is slightly smaller than at Nikiti-1 (55.1 mm), but much larger than at Piera (45.0 mm).

Metapodials

The metapodials, of the size of the fallow deer, are relatively small compared with Tragoportax from the same locality (see Annexe: Table 4) and slender. The widening from diaphysis to epiphysis is clearly bovid-like with abrupt change of width of the distal epiphysis compared to Tragoportax of the same locality. The trochlear keels are prominent and sharp. The lateral longitudinal grove specific to the metapodials of? M. pannoniae is absent here.

COMPARISONS

Comparison with ante-Turolian forms

The type of Miotragocerus (M.) monacensis from the Astaracian/Vallesian ( Stromer 1928) has horn-cores smaller than those of Hadjidimovo ( Fig. 15 View FIG ), and the temporal lines are stronger. The comparison with M. pannoniae is difficult because the type material is scarce, and moreover belongs to a subadult individual, and because referral of material from other localities is uncertain. From the horn-core from Inzersdorf supposed to represent an adult male of this species ( Thenius 1948), it differs mainly by the less straight posterior edge of the horn-core and probably by the smaller number of demarcations. From the Höwenegg sample described as M. pannoniae by Romaggi (1987) the Hadjidimovo skull material differs also by the curved (not straight) surface of the posterior horn-core wall as well as by the shorter horn-cores. The metatarsals of the M. ( Pikermicerus ) from Hadjidimovo lack the proximal lateral (and in some cases lateral and medial – at Höwenegg) longitudinal depression described for some Vallesian bones referred to M. pannoniae (see below). The differences of the M. (Pikermicerus) gaudryi sample from Hadjidimovo with the graceful horn-cores of the type of M. (M.) monacensis are clear. The comparison with the material of M. ( Pikermicerus ) “ cf. gaudryi ” from the late Vallesian of La Croix Rousse in France (data in Moyá-Solá 1983: 166) shows that both the metapodials and horn-cores of the Hadjidimovo material are clearly larger.

Comparison with the Turolian samples: M. gaudryi The differences between the accepted forms of M. gaudryi are mostly metrical. So, M. (P.) gaudryi (= Tragoportax gaudryi sensu Moyá-Solá 1983 and Bouvrain 1988) generally increases in size from early to late Turolian (Moyá-Solá 1983; Bouvrain 1988). The metrical data of the metapodials (Annexe: Table 4) as well as those of the mandibular/maxillar teeth and horn-cores (Annexe: Table 2; Figs 15 View FIG ; 17 View FIG ) show that the Hadjidimovo sample has larger body and teeth than M. gaudryi crusafonti from Piera (MN11, Spain; Moyá-Solá 1983: 137, 138). This locality has yielded a large number of boselaphine crania. However, some details of Moyá-Solá’s description and figures suggest that the sample might not be homogeneous, and perhaps include some Tragoportax . On the other hand, the lower teeth from Hadjidimovo (Annexe: Table 2) are smaller than the latest as well as largest known form, M. g. leberonensis from mont Lubéron (MN12- 13, France) and Venta del Moro (MN13 of Spain) (data in Moyá-Solá 1983: 161). The horn-cores from Hadjidimovo differ from those from Le Coiron, France, described by Romaggi (1987) as Graecoryx andancensis , by the lack of a strong curve backward, especially in females. The Hadjidimovo material is very close in skull and horn-core morphology as well as in dimensions to the material from the middle Turolian of the type locality, Pikermi (Annexe: Table 1 and Figs 15 View FIG ; 17 View FIG ). The Greek material from Samos ( Solounias 1981), as well as two undescribed frontlets from Veles-Karaslari could be included in the same form, M. (P.) gaudryi gaudryi .

DISCUSSION

The type species of Miotragocerus , M. monacensis Stromer, 1928 , was described from a partial skull from the Astaracian/Vallesian of Oberföhring on which the main cranial features of M. (P.) gaudryi cannot be observed because of its fragmentary nature but the horn-core cannot be distinguished from those of this species. So, Pikermicerus Kretzoi, 1941 can be considered as a junior synonym of Miotragocerus Stromer, 1928 and we can include in Miotragocerus all forms with short and robust horn-cores, with sub-elliptic basal section and with all diagnostic feature noted above (see Diagnosis).

The variability of Miotragocerus is not so great as that of Tragoportax . The differences noted in the literature are mostly metrical. As we have noted above, not all features observed in the more recent subgenus Pikermicerus could be observed in the older subgenus Miotragocerus , represented by scarce and incomplete material. The cranial differences between the two subgenera are at present restricted to: the shape of the horn-cores, with a straighter caudal edge in M. ( Miotragocerus ); the more prominent temporal lines and most probably some ratio differences in horncores and teeth: more massive (short and robust) horn-cores and possibly longer premolar row in M. ( Pikermicerus ). More material is needed to confirm this taxonomic (subgeneric) differentiation. If the characteristic lateral (as well as medial?) depression referred to “ Dystychoceras ” pannoniae metatarsals ( Tobien 1953; see also Romaggi 1987) as well as to some Spanish pre- Turolian Miotragocerus (Moyá-Solá 1983) really represents a stable character, this feature would be also highly diagnostic. In this case, Pikermicerus might represent a genus distinct from the earlier Miotragocerus , or “ pannoniae ” might belong to a different genus ( Dystychoceras ) rather than to Miotragocerus (see below).

Dystychoceras Kretzoi, 1941 is often interpreted in the recent literature as a synonym of Miotragocerus and the type species D. pannoniae Kretzoi, 1941 from the late middle Miocene of Sopron ( Hungary) as a species of the genus Miotragocerus (T h e n i u s 1 9 4 8; M o y á -S o l á 1983). The horn-cores of D. pannoniae (see Kretzoi 1941) are inserted very wide apart; they are incompletely preserved, but seem to have a thickening near mid-length not found in other species. It is usually accepted, following Thenius (1948), that the type of D. pannoniae and the skull fragments from Mistelbach and Inzersdorf (also very straight but with several demarcations) represent successive ontogenic stages of one and the same form. For this reason most authors include Dystychoceras in Miotragocerus ( Tobien 1953; Moyá-Solá 1983; Romaggi 1987). However, the horn-core A4264 (NHMW) from the Vallesian of Inzersdorf (even if from an adult individual) has a less flattened lateral surface and a more oval cross-sec- t i o n t h a n t h e h o l o t y p e o f Dystychoceras pannoniae , from Sopron. A frontlet similar to the one from Sopron was also found at Grizev in Ukraine and identified and figured as “ Dystychoceras ” in Korotkevich (1988). More findings are necessary to solve the Dystychoceras taxonomy problem.

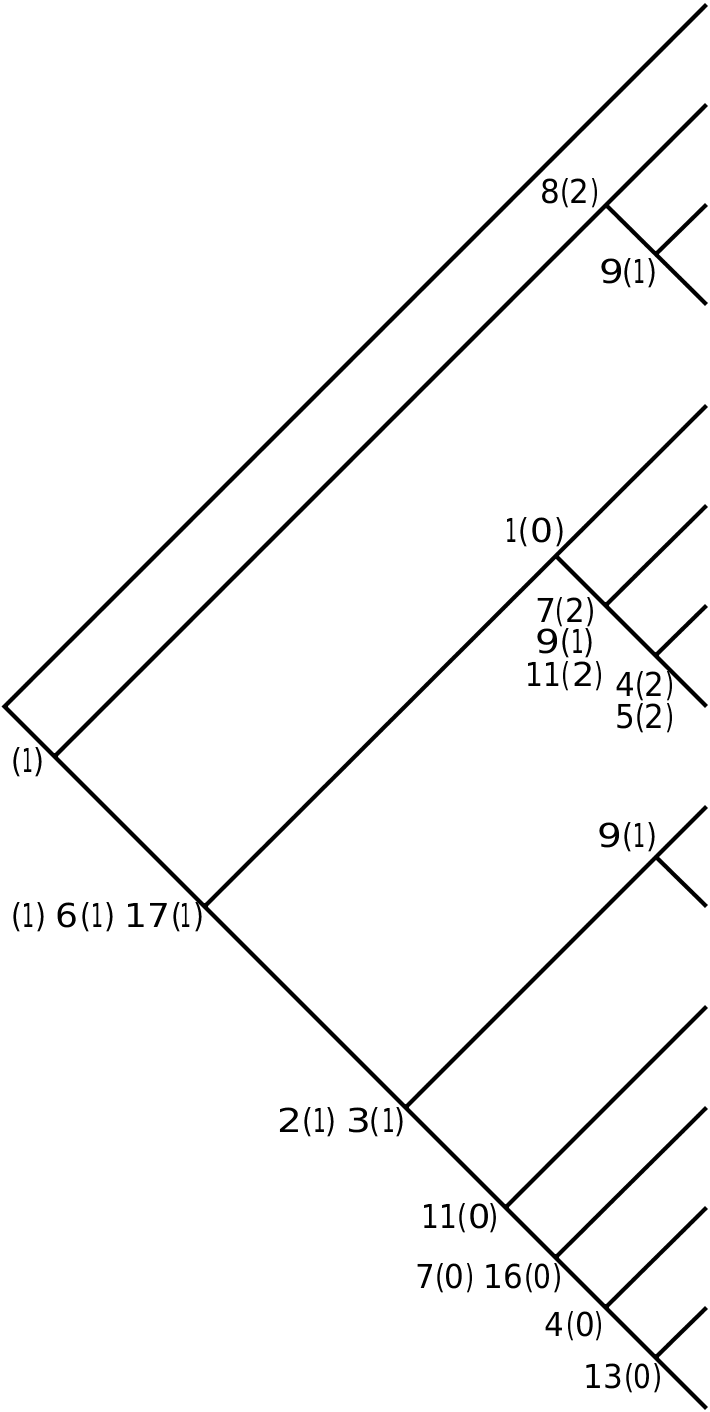

Tobien (1953) refers to “ M. ” pannoniae some metatarsals from Sopron and Eppelsheim with lateral longitudinal groove. The discovery of such metapodials in the Vallesian of Spain (Can Llobateres, Santiga) led Moyá-Solá (1983) to identify this material as M. aff. monacensis or M. pannoniae , by assuming that this metatarsal morphology is typical of this genus (versus Tragoportax sensu this author). As we have noted, lateral and medial depressions were described on the metatarsals from Höwenegg referred to M. pannoniae by Romaggi (1987). However, if “ M. ” pannoniae belongs to a genus distinct from Miotragocerus (see also the cladogram in Fig. 18 View FIG ), these metatarsals could belong to a distinct genus, Dystychoceras , not to Miotragocerus .

The referral of the pre-MN9 material from Spain (see Moyá-Solá 1983) to Miotragocerus is also doubtful. The horn-cores from Hostalets inferior as well as the horn-cores of Miotragocerus sp. from Puente de Vallecias, etc. (Moyá-Solá 1983) are very small and not very compressed laterally and do not display the typical features of Miotragocerus .

Bouvrain (1988) refers the Tragoportax material from Dytiko, Greece (MN13) to the “small form” – Tragoportax gaudryi (= M. (P.) gaudryi in our meaning) and creates a new subspecies, T. g. macedoniensis for it. Recently, Bouvrain (2001) includes this form in Dystychoceras . However, from our cranial criteria (the shape of the basioccipital and the presence of a fronto-parietal postcornual depression, a combination of features know only in Tragoportax ) the Dytiko form belongs to Tragoportax s.s.

As mentioned above, the skull of Mirabilocerus brevicornis from Arkneti, Georgia (Meladze 1967) displays some features of the genus Miotragocerus , but more detailed observations are necessary for a correct taxonomic decision.

One strongly laterally compressed horn-core from Weierburg (NHMW), with a length of c. 220 mm, a change of the curve of the apical part forward and a sub-oval basal section could represent the genus Miotragocerus .

M. (Pikermicerus) gaudryi is mentioned by Kostopoulos & Koufos (1996) in Nikiti-1 ( Greece, the very end of the Vallesian?), but the known horns are slender and could represent an earlier stage of the genus (see also Bouvrain 2001). M. (P.) gaudryi is also present at Nikiti-2 (MN11), together with Tragoportax , described by Kostopoulos & Koufos (1999). Indeed, some of the material described by these authors as Tragoportax aff. rugosifrons (for example the distal metacarpal NIK-428) belong instead to M. (Pikermicerus) gaudryi . This metapodial with a distal transverse diameter of 34.4 mm and a maximum antero-posterior diameter of 24.0 mm is too small for T. rugosifrons , but matches the size of M. (P.) gaudryi gaudryi (see Annexe: Tables 4; 5).

From our observations on the Mecquenem collection in the MNHN, Miotragocerus (Pikermicerus) is probably present also in the early Turolian of Maragha along with Tragoportax .

Thus, at least two and perhaps four species of Miotragocerus can be recognized: two pre- Turolian ones, M. (M.) monacensis and M. (M.) pannoniae (perhaps not of this genus), a larger mostly Turolian one, M. (P.) gaudryi (Kretzoi, 1941) and possibly a fourth one, the small “ Tragoportax (P.) aff. gaudryi ” sensu Moyá-Solá (1983) from the late Vallesian of Western Europe. There is a general trend of size increase in the successive subspecies of the Turolian form: from M. (P.) g. crusafonti from the early Turolian of Piera ( Spain) through the most widespread M. (P.) g. gaudryi from the so called “Greco-Iranian” province, to the late Turolian form from Western Europe, M. (P.) g. leberonensis. The early Turolian form from Le Coiron, “ Graecoryx andancensis ” (Romaggi in Demarcq et al. 1989) probably represents also a separate subspecies with strongly curved horn-cores, especially in females. The finds from Maramena, Greece (end of MN13) (Köhler et al. 1995) belong most probably to a relatively small M. gaudryi but the scarce material is not sufficient for definite conclusions. It may be that some of the known subspecies of M. (P.) gaudryi are in fact different at species level from the nominal subspecies of M. (P.) gaudryi but available data are insufficient, neither for an interpretation of the populations of M. (P.) gaudryi , nor for a comprehensive comparison with the Vallesian forms.

| NEW |

University of Newcastle |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

BOSELAPHINI Knottnerus-Meyer, 1907

| Spassov, Nikolai & Geraads, Denis 2004 |

Miotragocerus

| STROMER E. 1928: 36 |