Rhynchozoon glabrum, Dick & Grischenko & Mawatari, 2005

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.1080/00222930500415195 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03CE7B54-FF8B-FF83-DEDF-188888F3BED6 |

|

treatment provided by |

Felipe |

|

scientific name |

Rhynchozoon glabrum |

| status |

sp. nov. |

Rhynchozoon glabrum View in CoL , new species

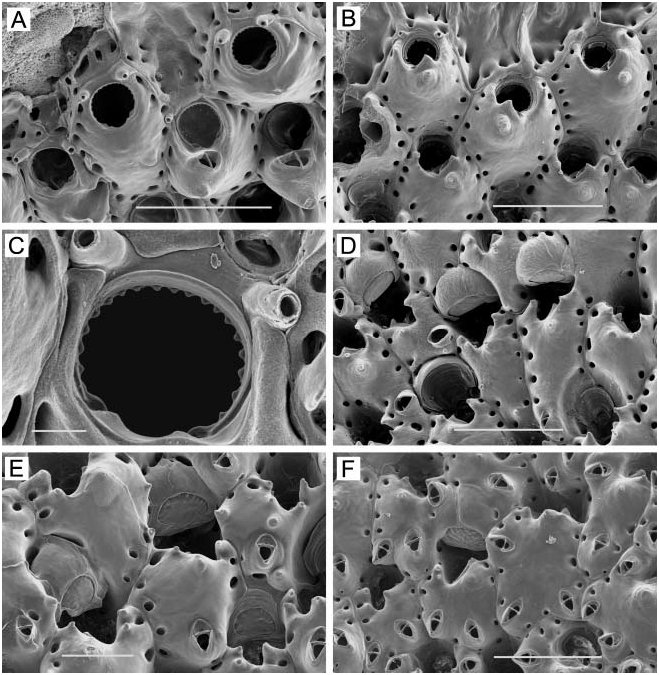

( Figure 26A–F View Figure 26 )

Diagnosis

Marginal zooids smooth or weakly costate, usually with two (rarely three) distal spines; with increased calcification, frontal wall becomes increasingly smooth and regular, rather than costate or rugose; with a tall or short, conical frontal umbo; orificial margin beaded with 15–26 rounded denticles; secondary orifice with one or two conical or finger-like projections at margin; three types of avicularia: suboral avicularium lying within peristome at later stages, proximal marginal avicularium, and one to three lateral marginal avicularia; both of the latter two types can be absent, or occur with or without the other.

Type material

Holotype: ETN, unbleached and uncoated ( YPM 35852) . Paratype 1: ETN, unbleached and uncoated (NHM 2005.7.11.9). Paratype 2: ETN, specimen Rhy-4a bleached and coated for SEM ( YPM 35853) . Paratype 3: HP, specimen Rhy-2a bleached and coated for SEM ( ZIRAS 1 /50532) . Paratype 4: HP, specimen Rhy-6a bleached and coated for SEM ( YPM 35854) . Paratype 5: HP, specimen Rhy-1a bleached and coated for SEM ( NMH 2005.7.11.10) .

Etymology

The species name derives from the Latin glaber, meaning smooth.

Description

Colony. Light tan or light chocolate- to violet-brown in colour; encrusting; unilaminar; multilaminar colonies were not observed; roughly circular; largest found 2.8 cm across.

Zooids. Irregularly hexagonal; marginal zooids 0.40–0.63 mm long (average 50.502 mm, n 515, 2) by 0.33–0.43 mm wide (average 50.349 mm, n 515, 2); young zooids delineated by a groove with a sharp incision at bottom; zooidal boundaries indistinct at later stages; basal wall completely calcified, often with several irregularly distributed white punctae up to 50 Mm in diameter. Zooids interconnect by unusual raised, disk-like dietellae scattered irregularly around the distolateral and distal walls, each with a single tiny pore in the centre.

Frontal wall. Shiny, vitreous; in marginal zooids markedly convex, inflated, smooth or weakly costate ( Figure 26A, B View Figure 26 ) between the 9–16 (average511.8, n 524, 3) areolar pores in total around margin, rapidly becoming thickened by a heavy layer of smooth calcification, without costation ( Figure 26B View Figure 26 ). Frontal wall increasingly smooth at intermediate and later stages of calcification, without ridges or irregularities, with a variably developed conical umbo that can be tall or short, blunt or sharp.

Orifice. Primary orifice ( Figure 26C View Figure 26 ) slightly broader than long; 0.11–0.13 mm long (average 50.127 mm, n 515, 2) by 0.11–0.15 mm wide (average 50.135 mm, n 515, 2), with a shallow, curved proximal sinus between a pair of triangular projections, flanked on each side by a conspicuous, rounded condyle; orificial margin beaded with 15–26 (average519.1, n 521, 4) regularly spaced, rounded denticles. With increased frontal calcification, primary orifice lies deep in peristome. Secondary orifice ( Figure 26D–F View Figure 26 ) irregular in shape; typically there is one process on the orificial rim on the same side as the suboral avicularium and two processes on the opposite side; sometimes two processes on each side; the processes vary from sharp and conical to cylindrical and finger-like, but are not developed as heavy tubercles. Frequently there is a broad pseudosinus between the lateral projection on one side and the base of the suboral avicularium, which lies within the peristome.

Avicularia. Three types occur. One is the asymmetrically positioned suboral avicularium, which arises initially as a bulbous chamber ( Figure 26A, B View Figure 26 ) from an areolar pore lateral to proximal margin of orifice, on one side or the other; rostrum directed laterally toward side of origin and tilted in frontal direction, with a hooked end; mandible long-triangular with a small hook at end. As frontal wall thickens, avicularian chamber becomes completely immersed, covered by the umbo, and avicularium comes to lie completely in peristome. In addition to suboral avicularium, zooids can have a single frontal avicularium along proximal zooidal margin ( Figure 26E View Figure 26 ), equal to or larger than suboral avicularium in size, with a non-hooked rostrum angled upward from the frontal surface, the mandible longtriangular, pointing proximally or sometimes laterally. At later stages, this avicularium can appear separate from the margin, positioned toward the centre of the frontal wall, surrounded by secondary calcification. Zooids can have a third type of avicularium; this is a frontal avicularium ( Fig. 26F View Figure 26 ) occurring anywhere along the lateral margins, one to three per zooid, equal to or smaller than the proximal frontal avicularium in size, with an equilateral or long-triangular mandible usually directed perpendicular to zooidal margin. In heavily calcified zooids, chamber of frontal avicularia (proximal and lateral) can become completely immersed, the rostrum scarcely raised above frontal surface. The complement of avicularia is variable; zooids within the same colony can have (in addition to the suboral avicularium) no frontal avicularia, only the proximal marginal avicularium, the proximal and one or more lateral avicularia, or one or more lateral avicularia and no proximal avicularium.

Spines. Marginal zooids usually have two distal spines ( Figure 26A–C View Figure 26 ), or rarely three. Spines sometimes longer than the zooid itself. Spines are ephemeral and restricted to marginal zooids; colony fragments without marginal zooids appear to lack them altogether.

Ovicell ( Figure 26D–F View Figure 26 ). Broader than long, 0.13–0.23 mm long (average 50.180 mm, n 522, 4) by 0.20–0.28 mm wide (average 50.237 mm, n 522, 4), the globose top exposed at first, but later weakly covered by frontal calcification from surrounding zooids; proximal face of ovicell lies in peristome and has a lumpy panel of exposed endooecium that is semicircular, blunt-triangular, transversely elliptical, or circular in shape, completely or incompletely bordered by ectooecium along the proximal margin. In fertile colonies, many zooids leave space for an ovicell before the ovicell develops; the result is a large secondary orifice that will be reduced in size when the ovicell forms.

Ancestrula . Not observed.

Remarks

Rhynchozoon glabrum overlaps in many characters with R. tumulosum . Primary orifice shape and ovicell form are indistinguishable; both species can have two spines on marginal zooids; both can have a tall frontal umbo proximal to the orifice; and both show some variability in the development of inter-areolar ridges on young, marginal zooids.

In a study of variation in the 16S mitochondrial ribosomal RNA gene among seven Rhynchozoon colonies at Ketchikan, Dick and Mawatari (2005) found two clades separated by 2.4% genetic distance (K2P + C). This permitted discrimination of morphological differences between the two lineages, which correspond to R. glabrum (Form A) and R. tumulosum (Form B). The two lineages are consistently distinguishable by a suite of morphological characters ( Dick and Mawatari 2005) that includes degree of frontal costation, range of spine number, number of beads on primary orifice, number of areolar pores, and peri-orificial sculpturing. Considered together, these characters usually allow a particular specimen to be identified. Rhynchozoon tumulosum tends to have more areolar pores and fewer orificial beads, though the ranges overlap considerably. Most marginal zooids of R. tumulosum have inter-areolar ridges early on ( Figure 25A, B), whereas most marginal zooids of R. glabrum lack them ( Figure 26A, B View Figure 26 ). In R. tumulosum , inter-areolar ridges are strengthened by fingerlike extensions of centripetal secondary growth over the primary frontal wall ( Figure 25D), leaving zooids slightly to markedly ridged at an intermediate stage of calcification ( Figure 25E, G) and with an irregular surface in advanced calcification ( Figure 25F); these finger-like extensions were not observed in R. glabrum . In R. glabrum , the frontal wall becomes increasingly smooth and regular with increased calcification ( Figure 26D–F View Figure 26 ). Marginal zooids in R. tumulosum can have two to five distal spines ( Figure 25A–C), although some colonies have zooids with predominantly two spines ( Figure 25B); zooids with more than two distal spines are rare in R. glabrum ( Figure 26A–C View Figure 26 ). Zooids of both species can either have or lack a single, proximal frontal avicularium, and can produce additional lateral frontal avicularia. However, the tendency to produce the lateral avicularia seems more pronounced in R. glabrum than R. tumulosum .

Distribution

A colony we have identified as R. glabrum is present on the same slide as Hincks’s (1882) type colony of R. tumulosum (NHM 1886.3.6.49) from the Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia ( Dick and Mawatari 2005). The known range of R. glabrum thus extends from Ketchikan to the Queen Charlotte Islands; however, previous records of R. tumulosum from farther south may have included this species.

| YPM |

Peabody Museum of Natural History |

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.