Phocoena phocoena

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6607321 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6607576 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/03B887D9-6B28-FFBE-FAA3-7CACF7E58B01 |

|

treatment provided by |

Diego |

|

scientific name |

Phocoena phocoena |

| status |

|

Harbor Porpoise

French: Marsouin commun / German: Schweinswal / Spanish: Marsopa comun

Other common names: Common Porpoise, Sea-hog, Sea-pig; Atlantic Harbor Porpoise, North Atlantic Harbor Porpoise (phocoena); Black Sea Harbor Porpoise (relicta); Eastern North Pacific Harbor Porpoise, Eastern Pacific Harbor Porpoise (vomerina)

Taxonomy. Delphinus phocaena Linnaeus, 1758 View in CoL ,

“Habitat in Oceano Europao & Balthico” (= Baltic Sea, “Swedish Seas”) .

In addition to the subspecies listed below, there is also an unnamed subspecies recognized from the western North Pacific Ocean. Three subspecies recognized.

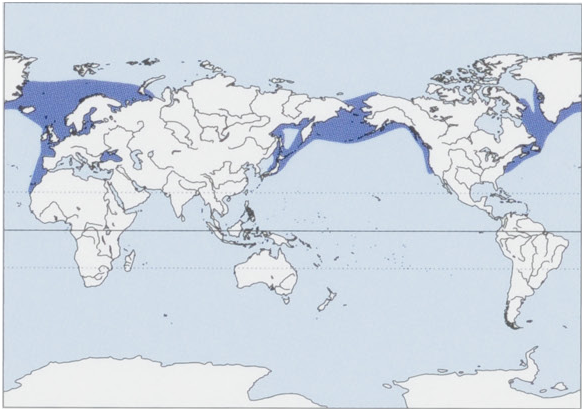

Subspecies and Distribution.

P.p.phocoenaLinnaeus,1758—coastalwatersoftheNAtlanticOcean.

P.p.relictaAbel,1905—coastalwatersof theBlackSea,theAzovandMarmaraseas(isolatedpopulation).AfewstragglersfromthispopulationshowupperiodicallyintheAegeanSea,buttheydonotoccurthroughoutmostoftheMediterraneanSea.

P.p. vomerina Gill, 1865 — coastal waters of the NE Pacific Ocean.

A still unnamed form is present in the coastal waters of the NW Pacific Ocean. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Total length 130-200 cm; weight 45-75 kg. Harbor Porpoises are small cetaceans, growing to a maximum length of only ¢.200 cm. Most adults are less than 180 cm long. Body is robust, with small appendages. There are small tubercles (or denticles) on the leading edge of the dorsal fin and sometimes also on flippers. Beak is very short and poorly defined, and dorsalfin is low, triangular, and wide-based. Color pattern is somewhat bland at first appearance, but it is actually more complex when analyzed in detail. Body is generally counter-shaded, with a dark gray back and white belly. Generally, dark and pale regions blend into each other, but margins between the two are often splotchy and streaked. Appendages are all dark, and there is a dark stripe running from gape to flipper, and there are also dark streaks on the lower jaw. There is a great deal of individual variation in color pattern, but no obvious differences among different populations have been identified. Thirty-four records of anomalously white individuals (three patterns have been observed, some perhaps albinos) have been recorded in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Newborns have a muted color pattern, generally of subdued tones of dark and pale gray. Tooth counts generally are 19-28 in each half of each jaw.

Habitat. Shallow waters throughout the temperate parts of the Northern Hemisphere, over the continental shelf, and usually near shore, although Harbor Porpoises may travel quite far from shore in some places and have been recorded in deep waters between land masses. They may also occur in deep waters in some inshore regions, such as in south-eastern Alaska, but only where there are shallow waters nearby. Habitat of the Harbor Porpoise is cool temperate to subpolar waters, generally with low water temperatures.

Food and Feeding. Harbor Porpoises are opportunistic feeders, although their main prey appears to vary on regional and seasonal scales. In the North Atlantic, they feed primarily on clupeoids and gadoids, while in the North Pacific, they prey largely on engraulids and scorpaenids. They eat a wide variety offish and cephalopods, although the diet in any specific area may be dominated by just a few species. Harbor Porpoises feed heavily on small schooling fish that occur in the water column, such as herring and sprat ( Clupeidae ), capelin (Mallotus), hake (Merluccius), and mackerel ( Scomber , Scombridae ); they also consume market squid ( Loligo ) in some areas. Although many of these prey species occur in the water column, many of the other prey species are benthic or demersal. Benthic invertebrates are sometimes also consumed, but these are generally considered to be secondarily ingested. In the north-eastern Atlantic, there has apparently been a long-term shift from predation on declining stocks of clupeid fish (mainly herring, Clupea harengus ) to sand lance ( Ammodytidae ) and gadoid fish.

Breeding. Reproductive biology of the Harbor Porpoise has been studied more extensively than for any other member of the family, due to the large number of specimens that have been available from strandings and incidental catches in fisheries. Mating system of the Harbor Porpoise is thought to be promiscuous. Anatomical evidence (Harbor Porpoises have some of the largest testes relative to body mass of any mammal species) has for some time suggested that sperm competition may be the primary way that males compete to inseminate females. Recent behavioral observations of Harbor Porpoises in the San Francisco Bay area (USA) appear to support this idea. Young are typically born in April-August (late spring through mid-summer), after gestation of ¢.10-11 months. Offspring are weaned before they reach one year of age. Sexual maturity occurs at 3—4 years of age and lengths of 120-150 cm. There is geographic variation in these parameters among different populations, and densitydependent variation has also been documented. Harbor Porpoises regularly interbreed and produce hybrids with Dall’s Porpoises ( Phocoenoides dalli ) in the inshore waters of the Pacific Northwest (Washington State, USA and southern British Columbia, Canada) and occasionally elsewhere where the two species are sympatric. It is virtually always the case that the mother is a Dall’s Porpoise and the father is a Harbor Porpoise, and this is what would be predicted, based on their respective mating systems (Dall’s are considered polygynous, with males apparently not using sperm competition, but guarding females to prevent insemination by other males). Harbor Porpoiseslive into their 20s, although in some areas most individuals may die before they reach twelve years of age.

Activity patterns. Harbor Porpoises are shy and unobtrusive animals, with a low surfacing profile and not a great deal of aerial behavior. They do not ride bow waves of vessels, and in many cases, they appear to actively avoid motorized vessels. There are exceptions to this, and at least in the San Francisco Bay area, they may be more approachable. These individuals sometimes lie nearly motionless at the surface for several seconds, and it is not clear why they do this. The typical surfacing pattern is a slow roll, in which the individual does not create any splash. At times, they do move faster and surface with a sloppy splash (this is called “pop-splashing,” and the splash looks very different from the more V-shaped splash of a rooster-tailing Dall’s Porpoise). Diving behavior of Harbor Porpoises has been studied with time-depth recording tags. Although most dives last less than one minute, Harbor Porpoises have been found to be capable of diving to depths of at least 220 m and for periods of more than five minutes.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Singles or small groups of less than a half-dozen Harbor Porpoises are most commonly seen, although they do aggregate, at times, into loose groupings of 50 to several hundred individuals. This occurs mostly when feeding on an aggregated food source or during migration, and these large groups generally have little structure. Movement patterns of individual Harbor Porpoises are not very well known, but it is known that they are capable of large-scale movements of many hundreds to thousands of kilometers. On the other hand, repeated sightings of identifiable individuals in San Francisco Bay show that some populations may have more limited movements. Not much is known about social organization of Harbor Porpoises, but most bonds outside the mother—offspring pair appear to be weak, and there do not seem to be any other long-term associations.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Least Concern on The [IUCN Red List. The subspecies relicta is classified as Endangered, and the Baltic Sea population, which only numbers ¢.500-600 individuals,is classified as Critically Endangered. Other subspecies have not been evaluated separately on The IUCN Red List. There has been a long and somewhat tragic history of human interactions with Harbor Porpoises. Hunting has occurred in many different parts ofits distribution, especially in northern European waters. Major hunts have occurred in the Black Sea, Baltic Sea, and the Bay of Fundy, and in the waters off western Greenland (the latter is still active). Many of these caused depletion of local populations. More recently, bycatch from fisheries, especially in various forms of gillnets or trammel nets, has been responsible for threatening existence of populations throughout the distribution of the Harbor Porpoise. The largest mortality has occurred in fisheries in the Gulf of Maine, western Greenland, North Sea, and Celtic Shelf, but smaller kills have occurred almost everywhere the Harbor Porpoise occurs. It is believed that Harbor Porpoises can normally detect gillnets at distances necessary to avoid entanglement, but accidents may happen due to attention shifts or auditory masking. Use of acoustic alarms (“pingers”) and other mitigation measures have managed to reduce mortality in many areas, but the only way to eliminate bycatch completely is to eliminate gillnets. Catches of Harbor Porpoises in trawls, set nets, herring weirs, pound nets, cod traps, and even anti-submarine nets have also been documented and have taken their toll. Other threats include detrimental effects of environmental contaminants, vessel traffic, anthropogenic noise impacts, prey depletion, and habitat deterioration or destruction. The Harbor Porpoise is not rare and not endangered. Globally, there may be more than 675,000 Harbor Porpoises. Nevertheless, particular populations in many areas have been impacted by human activities and quite a few of these are indeed threatened and in need of protection.

Bibliography. Amano (1996), Andersen et al. (2001), Barlow & Hanan (1995), Berggren & Wang (2008), Bjerge (2003), Bjerge & Tolley (2009), Borrell et al. (2007), Carretta et al. (2001), Caswell et al. (1998), Dahlheim et al. (2000), Fontaine & Barrette (1997), Forney (1999), Frantzis et al. (2001), Goodson & Sturtivant (1996), Haelters et al. (2012), Hammond et al. (2002), Heide-Jergensen & Lockyer (1999), Jepson et al. (2005), Keener et al. (2011), Kompanje & van Leeuwen (2009), Koschinski (2002), Larrat et al. (2012), Larsen (1997), Lockyer (2003), Lockyer & Andreasen (2004), Lockyer & Kinze (2003), McLellan et al. (2002), Nielsen et al. (2012), Northridge (1996), Palka (2008), Read (1999b), Read & Hohn (1995), Read & Westgate (1997), Rosel (1997), Rosel et al. (2003), Schofield et al. (2008), Siebert et al. (2006), Sonntag et al. (1999), Stenson (2003), Teilmann (2003), Thomsen et al. (2007), Tolley & Rosel (2006), Tonay et al. (2012), Verfuld et al. (2007), Viaud-Martinez et al. (2007), Westgate & Read (1998), Westgate & Tolley (1999), Westgate, Read, Berggren et al. (1995), Westgate, Read, Cox et al. (1998), Willis et al. (2004), Woodley (1995).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.