Melursus ursinus (Shaw, 1791)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5714493 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5714775 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/039D8794-F66F-C763-9097-7DF0FD46F213 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Melursus ursinus |

| status |

|

Sloth Bear

French: Ours paresseux / German: Lippenbar / Spanish: Oso bezudo

Other common names: Honey Bear, Lip Bear

Taxonomy. Bradypus ursinus Shaw, 1791 ,

Bihar (earlier Bengal), India.

Previously included in genus Bradypus = sloth. Two subspecies recognized.

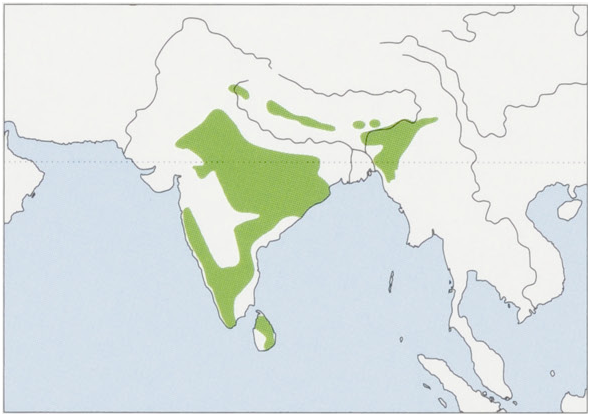

Subspecies and Distribution.

M. u. wrsinus Shaw, 1791 — India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Bangladesh.

M. u. inornatus Pucheran, 1855 — Sri Lanka. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 140-190 cm, tail 8-17 cm; weight of males 70-145 kg (rarely to 190 kg), females 50-95 kg (rarely to 120 kg). The Sri Lankan subspecies is smaller, and with a less-shaggy (shorter, sparser) coat than the nominate subspecies. Coat color is black, with rare brown or reddish-brown individuals. Hair length tends to be longer than in other bears, especially around the neck, shoulders, and back (up to 15-20 cm). The ears are also covered with long hair. Underfur is lacking, and ventral body hair is sparse. The muzzle has very short hair, and is distinctly light-colored up to the eyes. The lips are highly protrusible (hence this bear is sometimes called the Lip Bear), adapted for sucking termites, and the nose can be closed during such sucking, by pushing it against the side of the feeding excavation. The chest is normally marked by a prominent white V or U-shaped band. Sloth Bears have long (6-8 cm) slightly curved, ivory-colored front claws (for digging), and shorter rear claws. The long front claws (along with their coarse, shaggy coat and missing two upper incisors) are what seem to have caused an early taxonomist to call it a sloth. Soles of the feet are naked; unlike other bears, there is no hair between the digital pads and plantar pad on front and hindfeet, and also no hair separating the carpal and plantar (palmar) pad on the front. Unique among the bears, the digital pads are partially fused and are in a nearly straight line.

Habitat. Occupies a wide range of habitats on the Indian subcontinent, including wet and dry tropical forests, savannas, scrublands, and grasslands. Densities are highest in alluvial grasslands, and second-highest in moist or dry deciduous forests. Characteristically a lowland species, mainly limited to habitats below 1500 m, but ranges up to 2000 m in the forests of the Western Ghats, India. In Sri Lanka,it inhabits dry monsoon forests below 300 m. The climate throughout the range is monsoonal, with pronounced wet and dry seasons. This causes some variation in food habits and habitat use: very dry or very wet conditions can hamper feeding on termite colonies.

Food and Feeding. Sloth Bears are both myrmecophagous and frugivorous. Ants, termites, and fruit dominate their diet, with proportions varying seasonally and regionally. Fruits (from at least ten families of trees and shrubs) constitute up to 90% of the diet during the fruiting season in southern India and 70% in Sri Lanka, but less than 40% in Nepal, where fewerfruits are available. Sloth Bears more often eat fallen fruits off the ground than climb to eatfruits in trees. However, they will readily climb to consume honey. During the non-fruiting season, insects make up 95% of the diet in Nepal and 75-80% in S India and Sri Lanka. The relative proportion of termites to ants in the diet also varies considerably by region; in Nepal and Sri Lanka this ratio 1s more than 2:1, whereas in central India the ratio varies from about 1:1 to 1:5, favoring ants. Sloth Bears feed on termites by digging into their mounds or underground colonies, then alternately sucking up the termites and blowing away debris. These distinctive “vacuuming” sounds can be heard from 200 m away. Although most of their diggings are less than 60 cm deep, they occasionally dig down 1-2 m. Sloth Bears typically eat little vegetative matter other than fruits and some flowers, and they rarely prey on mammals or eat carrion. However, where their habitat is severely degraded by intensive human use and most of their normal foods are not available, they feed heavily on cultivated fruits and agricultural crops such as peanuts, corn, potatoes, and yams.

Activity patterns. These bears are more nocturnal than other bears, likely a response to the heat and sparse cover of their environment. Overall amount of activity varies widely, from 40-70% of the 24hour day, depending on conditions. In a national park in Nepal, with dense cover and moderate temperatures, most Sloth Bears are active both day and night, but are more active at night; conversely, subadults and females with cubs are diurnal, possibly to avoid being killed by nocturnal predators (Tigers) and other bears. In a park in Sri Lanka, with higher temperatures but dense cover, the bears are similarly more active at night and show lowerlevels of activity during the day. Where cover is much sparser, Sloth Bears often remain in shelter dens, usually crevices among boulders in rocky hillocks, the whole day, becoming active only near sunset. In central India, average daytime temperatures immediately outside shelter dens under a patchy (less than 25%) tree canopy, average 39°C (up to 44°C) compared to 28°C inside the dens. In winter, pregnant females den to give birth, whereas males and non-pregnant females remain active. It is unclear whether denning females actually undergo physiological hibernation in terms of reduced metabolism, recycling of body wastes, and preservation of muscle mass; they do not have large fat supplies to sustain them,like hibernating bears of other species, but they manage to survive without eating or drinking for 2 months. About 2 weeks before emerging from birthing dens with their cubs, they make nightly excursions from the den to feed.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Home ranges vary from very small (by ursid standards), averaging only 2 km? for females and under 4 km ” for males in Sri Lanka, to moderately small (9 km? for females, 14 km ® for males) in Nepal, to over 100 km? for some individuals in India. In an alluvial floodplain in Nepal, adult male bears shift to higher elevation, forested habitat during the monsoon and use areas nearly twice as large as during the dry season. Females and younger males also expand their ranges, but seem to avoid the upland areas dominated by adult males. Significant seasonal range shifts have not been observed in areas that do not seasonally flood. Bears living in protected areas with intact habitat rarely use adjacent degraded forests and agricultural areas. Movement paths are often highly circuitous, and rates oftravel for active bears are rather slow (maximum about 1 km /h) compared to other ursids, probably reflective of abundant foods. Home ranges extensively overlap, and bears may occasionally feed very close to other individuals without apparent social interaction; however, even in dense populations,it appears that adult females maintain areas of exclusive use within their range. Unrelated subadults have been observed to join together for several weeks, and sibling subadults to stay together for up to 19 months after leaving their mother, possibly as coalitions against attacks by older bears or other predators. Females ultimately settle near their mothers. Subadult males are presumed to disperse, but empirical data are lacking.

Breeding. Mating generally occurs from May to July. Males congregate near estrous females and fight for mating access. Females mate with multiple (often 3) males in the order of their established dominance, related largely to weight, and males mate with multiple females. Male-female pairs mate multiple times over a period of one hour to 1-2 days; copulations last 2-15 minutes. Females generally remain in estrus for only two days, rarely up to one week. Cubs are born from November through January. The 4-7 month gestation includes a period of delayed implantation. The birthing season may be somewhat lengthened in Sri Lanka, although previous reports of cubs being born throughout the year have not been corroborated by recent studies. Cubs are born in dens, either natural caves or holes excavated by the mother, and emerge with their mother at 2-2-5 months of age. The most common littersize is two cubs, although in some populations litters of one are also common; it is not known whether the latter represents cub mortality shortly after birth or small litters at birth. Litters of three are rare. Females have trouble raising litters of three because they carry their cubs on their back, and the third cub, carried over the hips, may bounce off. The long hair near the mother’s shoulders is a preferred riding place because it provides a better grip for the cub. Cubs remain on the back even when the mother vigorously digs for termites in deep holes (more than 1 m). Mothers with cubs on their back travel more slowly than bears without cubs. Cubs ride either head first or crosswise for 6-9 months (by which time they are each about one-third the mass of the mother), increasing their time on the ground as they age. When threatened, they scamper to their mother’s back for refuge rather than climbing a tree, probably an adaptation to living in an environment with few trees and formidable predators (Tigers), some predators that can climb trees (Leopards), and large animals that can knock over trees (elephants, rhinoceroses). Cubs nurse for 12-14 months, and remain with their mother for either 1-5 or 2-5 years, so litter intervals are either two or three years.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Listed as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. Sloth Bears are also protected to varying degrees by national laws in all five range countries. However, they can be killed to protect life or property; this is not uncommon, given their aggressive nature and increasing numbers of encounters between bears and people, often resulting in human casualties. Although no reliable large-scale population estimates exist for this species, best guesstimates indicate about 20,000 or fewer animals rangewide. Substantial fragmentation and loss of habitat suggests that their population has declined by more than 30% over the past 30 years. The recent possible extirpation of Sloth Bears in Bangladesh highlights serious concerns over persistence of small, isolated Sloth Bear populations throughout their range. Populations appear to be reasonably secure inside protected areas, but are faced with deteriorating habitat and direct killing outside. About half to two-thirds of the Sloth Bears in India live outside protected areas, and half the occupied range in Sri Lanka is not protected. Habitat has been lost, degraded, and fragmented by overharvest of forest products (timber, fuelwood, fodder, fruits, honey), establishment of monoculture plantations (teak, eucalyptus), settlement of refugees, and expansion of agricultural areas, human settlements, and roads. Commercial trade in bear parts has been reported, but its current extent and impact on Sloth Bears is uncertain. Poaching also occurs for local use (e.g. male reproductive organs used as aphrodisiac; bones, teeth and claws used to ward off evil spirits; bear fat used for native medicine and hair regeneration). Capture of live cubs to raise as “dancing bears” remains a significant threat in some parts of India because laws against this are not adequately enforced. Some non-governmental organizations have been rescuing these bears (although they cannot be released to the wild) and training the people who hunted them in alternate types of work, in exchange for a commitment that they will not resume the practice.

Bibliography. Akhtar et al. (2004, 2007), Bargali et al. (2004, 2005), Chhangani (2002), Garshelis, Joshi & Smith (1999), Garshelis, Joshi, Smith & Rice (1999), Garshelis, Ratnayeke & Chauhan (2007), Japan Bear Network (2006), Joshi, Garshelis & Smith (1995, 1997), Joshi, Smith & Garshelis (1999), Laurie & Seidensticker (1977), Rajpurohit & Krausman (2000), Ratnayeke, Van Manen & Padmalal (2007), Ratnayeke, Van Manen, Pieris & Pragash (2007), Yoganand et al. (2006).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.