Helarctos malayanus (Raffles, 1822)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.5714493 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5714773 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/039D8794-F668-C762-90B1-7702F8A9FE0F |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny |

|

scientific name |

Helarctos malayanus |

| status |

|

Sun Bear

Helarctos malayanus View in CoL

French: Ours malais / German: Malaienbar / Spanish: Oso malayo

Other common names: Malayan Sun Bear, Dog Bear, Honey Bear

Taxonomy. Ursus malayanus Raffles, 1822 View in CoL

[ presented orally in 1820, often incorrectly ascribed as 1821], Sumatra, Indonesia.

Cranial differences support separation into two subspecies.

Subspecies and Distribution.

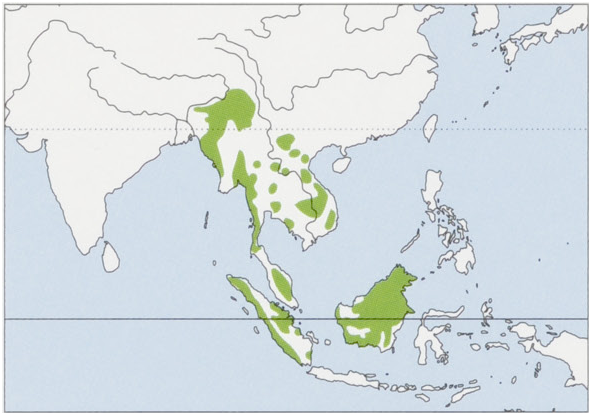

H. m. malayanus Raffles, 1822 — Bangladesh, NE India, and S China (Yunnan) through SE Asia to Malaysia, and Sumatra.

H. m. euryspilus Horsfield, 1825 — Borneo. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body 100-150 cm, tail 3-7 cm; weight 30-80 kg. Males are heavier than females, but the degree of sexual dimorphism (10-20%) is less than most other bears. The Bornean subspeciesis notably smaller, with a maximum weight of 65 kg. The body is stocky, and compared to other bears, the front legs more bowed, front feet turned more inward, muzzle shortened, ears especially small, and hair very short, often with obvious whorls. Coat coloris black or less commonly dark brown, typically with a prominent white, yellow, or orange chest marking. The chest marking is highly variable among individuals, usually a U or circular shape, but occasionally more amorphous, and sometimes with dark patches or spots. The bear takes its common name from this marking, which may look like a sun. The muzzle is pale, and the forehead may be wrinkled. The exceptionally long tongue (20-25 cm) is used for feeding on insects and honey. The canine teeth, which are particularly large in relation to the head, and the large front feet with long claws, are used for breaking into wood (e.g. to prey on stingless bees) and termite colonies. Soles of the feet have little hair.

Habitat. In mainland South-east Asia, where there is a prolonged dry season, Sun Bears inhabit semi-evergreen, mixed deciduous, dry dipterocarp, and montane evergreen forest, largely sympatric with Asiatic Black Bears. In Borneo, Sumatra, and peninsular Malaysia, areas with high rainfall throughout the year, they inhabit mainly tropical evergreen dipterocarp rainforest and peat swamps. They also use mangrove forest and oil palm plantations in proximity to other, more favored habitats. They occur from near sea level to over 2100 m elevation, but are most common in lower elevation forests.

Food and Feeding. Omnivorous diet includes insects (over 100 species, mainly termites, ants, beetles and bees), honey, and a wide variety of fruits. In Bornean forests, fruits of the families Moraceae (figs), Burseraceae and Myrtaceae make up more than 50% of the fruit diet, but consumption of fruits from at least 20 other families of trees and lianas were identified in just one small study site (100 km?) in East Kalimantan. Availability of foods varies markedly from masting years when most species fruit synchronously, to inter-masting years when little fruit is available and the bears turn mainly to insects. Figs ( Ficus ) are a staple food during inter-mast periods. On the mainland, fruiting is more uniform (predictable) from year to year, but varies seasonally. However, there is an enormous diversity of fruits, so some fruit is available at all times of year. In Thailand, about 40 families of trees are climbed by Sun Bears, mostly for food; fruits from Lauraceae (cinnamon) and Fagaceae (oak) are favorites. Sun Bears are especially known for preying on colonies of stingless bees (7Trigona), including their resinous nesting material. The bees form nests in cavities of live trees, so to prey on them Sun Bears chew and claw through the tree, leaving a conspicuous hole. These bears consume little vegetative matter, although they seem to relish the growth shoots of palm trees (palm hearts), the consumption of which kills the tree. Occasionally they also take reptiles, small mammals, and bird eggs.

Activity patterns. Activity has been described as mainly nocturnal or mainly diurnal. This variability depends on proximity to human activities: in heavily disturbed areas, such as oil palm plantations, Sun Bears are chiefly nocturnal. Camera traps along roads typically obtain photographs of bears mainly at night, whereas signals from radio-collared bears farther from roads indicate that they are active mainly during the day. They spend a large proportion of time feeding in trees when fruit is abundant. They also sometimes build tree nests of branches and leaves for sleeping. This behavior has been attributed to previous predation pressure by Tigers; however,it appears to occur commonly only in heavily-disturbed forests or near people. Sun Bears have been observed to slide rapidly down tree trunks when disturbed by people. Although arboreally adept, they cannot swing orjump from tree to tree. Normally they sleep on the ground, often in cavities of either standing or fallen trees, or under such trees. Females use similar sites for birthing dens. This species does not hibernate.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Home range information is very limited. Two males radio-tracked for about one year in Borneo during a fruiting failure had minimum known ranges of 15-20 km? (butlikely ranged beyond this); one of them centered his activity on a garbage dump. Two Bornean females living in a small, isolated forest patch (100 km? more than half of which had been burned in a forest fire and was rarely used by Sun Bears) had home ranges of only about 4 km ®. Most sightings have been ofsolitary bears or mothers with a cub, but gatherings of multiple bears have been witnessed at rich feeding sites.

Breeding. This is the only species of bear without an obvious breeding and birthing season. Cubs are born during all months, both in captivity and in the wild. However, data have not been collected across the range, so it is possible that greater reproductive seasonality occurs in areas with strongly seasonal environments. Females have four teats, but maximum observed litter size is two, and normal litter size is only one. Captive-born cubs have shown an unusual female bias. The gestation period in captivity is much shorter than in other bears: it is normally 3-3-5 months (indicating a shortened or nonexistent period of delayed implantation), but in a few odd cases stretched to 6-8 months, like most other bears. Mating in captivity occurs at 3-6 month intervals if pregnancy does not result. If cubs die, estrus reoccurs in 2-5 weeks, making the interbirth interval as short as 4-4-5 months. No information is available on normal cub dependency or intervals between litters in the wild. The earliest known age of estrus in the wild is three years old. Birthing takes place in a secluded den. In captivity, mothers sometimes carry their cub in their mouth, suggesting that bears in the wild may be able to move dens occasionally after the cub is born.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Listed as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List. Although quantitative estimates of population sizes and trends are lacking, rates of habitat loss and degradation, combined with persistent poaching, indicate that the global population ofthis species has declined by more than 30% during the past three decades. Additionally, it is strictly protected under national wildlife laws throughout its range; however, there is generally insufficient enforcement of these laws. None of the eleven countries where the Sun Bear occurs has implemented any conservation measures specifically for this species. Commercial poaching, especially for gall bladders (used in traditional Chinese medicine) and paws (a delicacy), is a considerable threat, especially in mainland South-east Asia. Local hunters in one area of Thailand estimated that commercial poaching reduced the abundance of Sun Bears by 50% in 20 years. In Malaysia and Indonesia, deforestation is the prime threat. Clear-cutting to expand oil palm (Elaeis guineenis) plantations (which is likely to worsen with increased biofuel production) and unsustainable logging (both legal and illegal) are escalating at alarming rates. Prolonged droughts, spurring natural and human-caused fires, are compounding the habitat-loss problem, resulting in diminished availability of food and space for bears, sometimes causing their starvation. Where bears do not die directly from food scarcity, they seek out agricultural crops adjacent to the forest, and are poisoned or trapped and killed by local people. Some headway has been made in establishing buffer zones around protected forested areas, educating local people on nonlethal deterrents, and increasing communication between local people and sanctuary managers, resulting in shared problem solving.

Bibliography. Augeri (2005), Fredriksson (2005), Fredriksson, Danielsen & Swenson (2007), Fredriksson, Steinmetz et al. (2007), Fredriksson, Wich & Trisno (2006), Hesterman et al. (2005), Japan Bear Network (2006), McCusker (1974), Meijaard (1999a, 1999b, 2001, 2004), Normua et al. (2004), Schwarzenbergeret al. (2004), Steinmetz & Garshelis (2008), Steinmetz et al. (2006), Wong, Servheen & Ambu (2002, 2004), Wong, Servheen, Ambu & Norhayati (2005).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.