Tapirus pinchaque, Roulin, 1829

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5721161 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5721235 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/039CED53-FFC5-FF8A-FAB2-21BE16799315 |

|

treatment provided by |

Conny (2021-10-07 23:52:38, last updated 2024-11-29 13:46:58) |

|

scientific name |

Tapirus pinchaque |

| status |

|

Mountain Tapir

French: Tapir des Andes / German: Andentapir / Spanish: Tapir de montana

Other common names: Andean Tapir, Woolly Tapir

Taxonomy. Tapir pinchaque Roulin, 1829 ,

Paramo de Sumapaz, Cundinamarca, Colombia.

This species is monotypic.

Distribution. The species is known to occur in the Andean areas of Colombia, Ecuador, and N Peru; historically also in W Venezuela, but now extirpated. View Figure

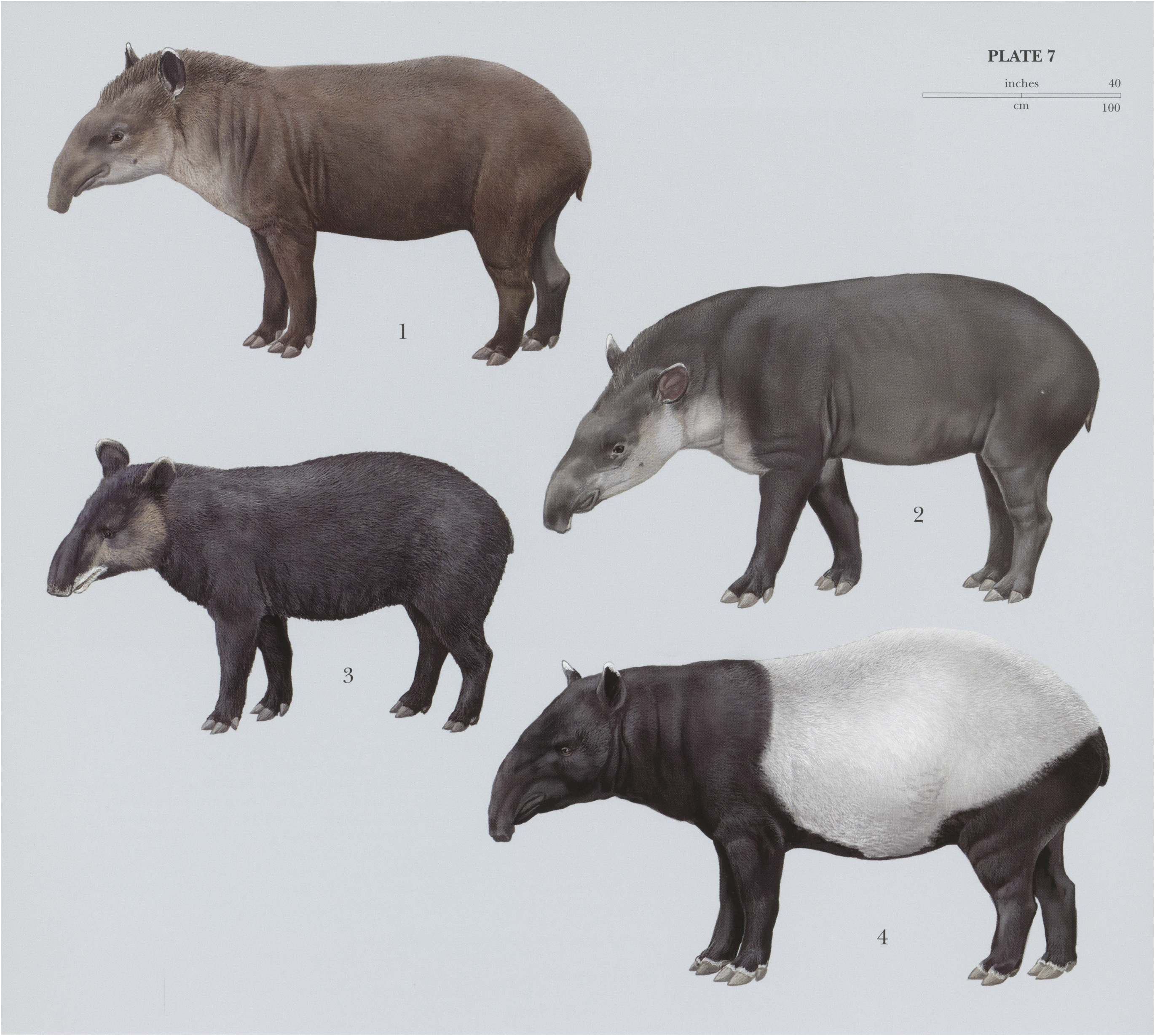

Descriptive notes. Head-body 180-200 cm, tail less than 10 cm, shoulder height 80-90 cm; weight 150-200 kg. The Mountain Tapir is the smallest of the four tapir species. Nevertheless,it is the largest terrestrial mammal in the Andes. Females tend to be slightly larger than males but this is generally indistinguishable in the wild. Newborn Mountain Tapirs usually weigh 4-7 kg. Adults have dark brown to coal-black fur, with white furry fringes around the lips, hoofed toes, and usually the tips of the rounded ears. The fur is 3-4 cm long. The species is adapted to live at high elevations with its thick undercoat and long, woolly outercoat, which both insulates and absorbs heat from the sun, providing protection against the cool night temperatures. The eyes are a glazy bluish-brown. Its splayed hooves allow it considerable versatility for locomotion in the high Andes, even on the snow banks and glaciers.

Habitat. The five major habitat types for Mountain Tapirs are chaparral, tropical montane (Andean) forests, paramos, ecotones, and riverine meadows between 2200 m and 4800 m. Mountain Tapirs rarely use open habitats (pampas), in spite of the considerable quantity and quality of food available. In Los Nevados National Park, Colombia, Mountain Tapirs selected secondary forests, avoided paramos and ecotones, and showed no preference for or against mature forests. Their density in secondary forests was higher than in mature forest, ecotones, and paramos. Bedding sites are frequently encountered in forest thickets. In areas with cattle, the tapirs tend to be found on steep, forested mountain slopes inaccessible to cattle.

Food and Feeding. Mountain Tapirs are classified as selective browsers according to their craniodental patterns and dental morphology. The Mountain Tapir diet includes a variety of understory plant species including herbs, grasses, shrubs, fruits and berries, twigs, and a predominance ofleaves. A field study in Ecuador showed that of 28 plant families, Asteraceae ranked highest in the number of different species eaten, followed in diminishing order by Gramineae , Rosaceae , Cyperaceae , Fabaceae , Scrophulareaceae, and Valerianaceae . The same study indicated that Mountain Tapirs select certain favored plants regardless of their relative abundance. Flower parts were noted in five out of 37 fecal samples. A more recentfield study in Colombia showed that a total of 109 species of plants were consumed, and 45 of them were strongly selected. Mountain Tapirs consumed 54% woody species, 30% herbs, and 16% grasses. Once again, Asteraceae was the most frequent family in the Mountain Tapir diet. Patches of Chusquea make up a high proportion of secondary forest vegetation in Los Nevados National Park and make up a large part of the tapirs’ diet. The Mountain Tapir uses the sensitive bristles on the tip of its proboscis, as well as its senses of smell, taste, and, to a lesser degree,sight in selecting palatable items. Like other tropical species living in areas of high rainfall, the Mountain Tapir depends upon supplementary mineral intake from mineral seeps and natural saltlicks. Additionally, Mountain Tapir occasionally eat certain types of clayish mud, according to native Puruhaes Indians.

Breeding. There is virtually no information about reproduction of Mountain Tapirs in the wild. Adult females produce a single offspring after a gestation period of 13-14 months (390-410 days). Twin births have never been recorded. Estrus lasts 3—4 days and is on a lunar cycle. A Mountain Tapir Population and Habitat Viability Assessment (PHVA) Workshop held in 2004 modelled the dynamics of mountain tapir populations in the wild. The age of first reproduction was estimated to be three years for females and four years for males. Maximum age of reproduction was estimated to be 15 (+ 3) years for both sexes. The generation length of wild Mountain Tapirs was estimated to be eleven years. Male Mountain Tapirs are reported to engage in violent confrontations over females.

Activity patterns. Daily activity of Mountain Tapirs in Los Nevados National Park, Colombia, was clearly bimodal, with peaks in the early hours of the day (05:00-07:00 h) and early hours of the evening (18:00-20:00 h). In the cloud forests and wet paramos of Ecuador, the activity of a young Mountain Tapir was higher during the morning (07:00-09:00 h) and late afternoon /evening (15:00-21:00 h). Increased nocturnal activity may be witnessed in areas with a greater presence of humans and livestock. In Colombia,it has been hypothesized that the Mountain Tapir is more active at higher elevations (i.e. paramos and the upper limit of montane forests) during the dry season; during the wet season, activity increases at lower elevations. Apparently, domestic livestock management activities during the dry season at lower elevations forces the tapirs to move to paramos. A camera-trap study carried out in Los Nevados National Park revealed higher Mountain Tapir nighttime activity along trails and at a natural lick during the full moon.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. Very little is known about the spatial ecology, intraspecific interactions and social organization of Mountain Tapirs. GPS telemetry was used to monitor a few individuals in Los Nevados National Park, Colombia. The estimated mean home range size was 2-5 km*. Home range size did not seem to vary seasonally. Home ranges of adults overlap by as much as a third, with a core territory belonging to the male, his mate, and offspring. Males show greater fidelity to their more circular territory and are more likely to defend territories than females. Markings by dung piles and rubbings on trees seem to be part of the territorial behavior of males as well as females who share the same territory. Urinary demarcation has been noted and is often associated with an instinctive pawing of the hindfoot. Mountain Tapir density estimates appear to be much lower when compared to South American and Central American Tapirs. The Mountain Tapir density estimated through telemetry in Sangay National Park, Ecuador, was 0-17 ind/km?. In Los Nevados National Park, Colombia, a GPS telemetry study resulted in an estimate of 0-1 ind/km?®. Density estimates based on track counts were 0-18 ind/km? in Los Nevados and 0-25 ind/km? in the Parque Regional Ucumari, also in Colombia.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix I. Classified as Endangered on The [UCN Red List. In Colombia, it occurs in the central Andes, south of Los Nevados National Park, and in the eastern Andes, south of Paramo de Sumapaz, near Bogota. There are no Mountain Tapirs in the Western Cordillera, northern part of the Central and Eastern Cordilleras, Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Serrania de la Macarena, and Cerro Tacarcuna. Nevertheless, there are reports of their presence (footprints, feces, and poaching remains) in the junction of the Central and Eastern Cordilleras of Colombia. In Ecuador, Mountain Tapirs are found in the eastern Andes, including Sangay National Park, Llanganates National Park, Podocarpus National Park, and Cayambe Coca Ecological Reserve. In Peru, the species is distributed from the Ayabaca province, Piura Department (04° 20 ° S) in the Western Cordillera to the Chota Province, Cajamarca Department (06° 20 ° S) in the Eastern Cordillera. In the southern part of the distribution in Peru, the species occurs in the Huancabamba depression, which includes the Tabaconas-Namballe National Sanctuary and the Pagaibamba Protection Forest. Historically, the species has been recorded in Venezuela, in the vicinities of El Tama National Park, opposite the north Santander State of Colombia. However, there is no recent evidence ofits occurrence in the area. The most threatened populations are those of the Central Cordillera in Colombia, between Parque Natural Las Hermosas and Parque Natural Nevado del Huila, where large tracts of mature montane forests are being converted to opium fields. The Mountain Tapir is now extinct in much of its former range. The major threat to the Mountain Tapir throughoutits range is human population growth in the Andean region. People settling in the region need land, consumables, and services, and their activities lead to habitat destruction. Mountain Tapir population declines have been estimated to be greater than 50% in the past three generations (33 years). It has been predicted that that there will be a decline of at least 20% in the next two generations (22 years). The low reproductive rates and slow population growth characteristic of tapir species, coupled with habitat loss and fragmentation and hunting, are the major factors contributing to population declines. Habitat fragmentation is caused by conversion of forests and paramosto cattle ranching and agricultural lands. There is significant hunting pressure on this species. It is extremely rare to encounter an area with Mountain Tapirs where they are not being overhunted. Local poachers use the tapir skin to manufacture working tools (e.g. backpacks, ropes to ride horses, baskets) and domestic artifacts such as carpets and covers for beds. In addition, poachers sell tapir skins and feet for medicinal purposes. Additional threats include the development of hydroelectric dams, highways crossing protected areas, petroleum exploration, and electrical networks. Road construction is a major threat in Puracé National Park, Colombia. There has also been widespread cattle introduction into the last remaining patches of Mountain Tapir habitat, which leads to competition for food resources and a potential risk of transmission of infectious diseases and other etiological agents carried by the cattle. Cattle have been observed forming reproducing herds in western Sangay National Park in Ecuador, causing Mountain Tapirs to abandon areas north of Sangay Volcano. Information from other areas where the species is found (Cayambe Coca Ecological Reserve in Ecuador, Tabaconas-Namballe National Sanctuary in Peru, and Natural Parks in Colombia) indicates that the same problem with cattle is occurring there, too, and negatively affecting the species. Other threats include cattle roundups, which can result in increased hunting of the tapirs; poppy growing and eradication; and guerilla warfare in Colombia. The presence of guerillas may benefit the tapirs by halting settlement of some areas, but most local biologists feel that the overall impact on the conservation of Mountain Tapirs is negative. In addition, a mining project in northern Peru threatens to destroy the headwater cloud forest and paramo habitat of a scant population of Mountain Tapirs. It has been estimated that fewer than 2500 mature individuals still remain in the wild. The Mountain Tapir population in Peru has been estimated to be approximately 450 individuals. There is no connectivity between the northern and southern Mountain Tapir populations in Peru. The area of suitable habitat for the Mountain Tapir inside National Parks in Colombia is 13% ofthe total area where tapirsare still found. In the Andes of Colombia, there are 23 National Parks, of which tapirs are found in only seven (Cordillera de los Picachos, Cueva de los Guacharos, Las Hermosas, Los Nevados, Nevado del Huila, Puracé, and Sumapaz). Legal protection of the speciesis in place in Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, but law enforcement is not effective.

Bibliography. Acosta et al. (1996), Brooks et al. (2007), CITES (2005), Davalos (2001), Diaz et al. (2008), Downer (1996, 2001, 2003), Hershkovitz (1954), Lizcano (2006), Lizcano & Cavelier (2000a, 2000b, 2004), Lizcano & Sissa (2003), Lizcano, Cavelier & Mangini (2001), Lizcano, Guarnizo et al. (2006), Lizcano, Mangini et al. (2001), Lizcano, Medici et al. (2005), Lizcano, Pizarro et al. (2002), Medici (2001, 2010), Ministerio del Medio Ambiente de Colombia (2002), Schauenberg (1968, 1969), Schipper et al. (2008), Semple (2000), Suarez-Mejia & Lizcano (2002), Thornback & Jenkins (1982), Tirira (1999).

1. Lowland Tapir (Tapirus terrestris), 2. Central American Tapir (Tapirus bairdii), 3. Mountain Tapir (Tapirus pinchaque), 4. Malayan Tapir (Tapirus indicus)

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

1 (by conny, 2021-10-07 23:52:38)

2 (by ExternalLinkService, 2021-11-23 14:52:06)

3 (by ExternalLinkService, 2021-11-23 14:57:30)

4 (by ExternalLinkService, 2021-11-23 15:22:38)

5 (by GgImagineBatch, 2022-04-14 05:50:48)

6 (by conny, 2022-05-03 11:11:16)

7 (by ExternalLinkService, 2022-05-03 11:19:01)

8 (by ExternalLinkService, 2022-05-03 11:44:21)

9 (by tatiana, 2022-05-25 14:15:45)

10 (by plazi, 2023-11-08 04:19:42)

11 (by ExternalLinkService, 2023-11-08 15:54:21)