Semnopithecus johnii (Fischer, 1829)

|

publication ID |

https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.6867065 |

|

DOI |

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6863450 |

|

persistent identifier |

https://treatment.plazi.org/id/CE199B17-FFAF-FFAB-FFEE-6254F97AFE3E |

|

treatment provided by |

Jonas |

|

scientific name |

Semnopithecus johnii |

| status |

|

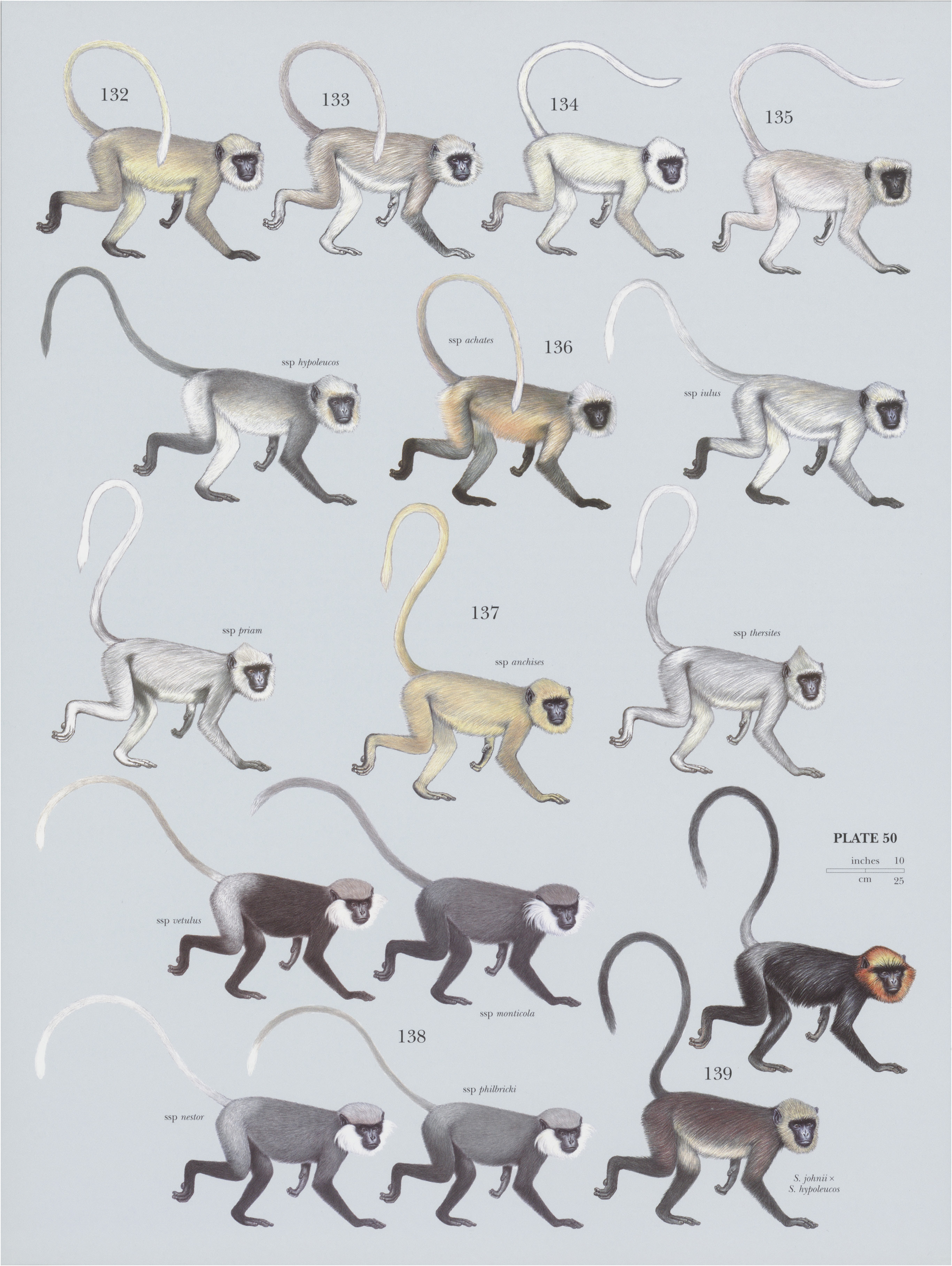

139. View Plate 50: Cercopithecidae

Nilgiri Langur

Semnopithecus johnii View in CoL

French: Langur des Nilgiri / German: Nilgiri-Langur / Spanish: Langur de Nilgiri

Other common names: Black Leaf Monkey, Hooded Leaf Monkey, Indian Hooded Leaf Monkey, John's Langur, Nilgiri Black Langur, Nilgiri Leaf Monkey, South Indian Black Leaf Monkey

Taxonomy. Cercopithecus johnii Fischer, 1829 ,

India, Tellicherry.

Molecular data support the classification of the gray or Hanuman langurs, S. vetulus , and S. johnii , in the same genus, Semnopithecus . There is some apparent geographic variation in the presence and extent of silvering on the rump. In the northern part of the distribution, it is quite conspicuous, even extending forward onto the back or backward along the tail. S. johnii is believed to hybridize with S. hypoleucos where sympatric. Such crosses tend to be brownish. Monotypic.

Distribution. SW India ( Karnataka , Kerala, and Tamil Nadu states); it occurs sporadically in montane forests of the Western Ghats from Srimangala (12° 01’ N, 75° 58’ E) in Karnataka S to the Aramboli Pass (8° 16’ N) in Kerala. View Figure

Descriptive notes. Head-body ¢.78 cm (males) and c.58-4 cm (females), tail 68.5-96 cm; weight 11.8-13.6 kg (males) and 9.8-11.3 kg (females). Coat of the Nilgiri Langur consists of glossy black hairs with brown bases. Old individuals have white hair on back and rump. Face is black to purplish-red, and crown, sides of head, and cheeks are a light brown to vivid brownish-orange, becoming yellowish-brown on nape and sometimes on brow; contrast between these bright and dark areas is quite startling and is further accentuated by a narrow black brow fringe. Crown hairs are posteriorly directed. Tail is black, although sometimes partly silvery-gray at the base, the color extending to the rump. Sexes are similar, but females are alone in having small patches of white fur on insides of their thighs, which are present even in very young individuals. Males have larger canines than females. Differences in coat color have been recorded at Agastya Mali, the most southerly hill range in the Western Ghats. Specifically, they were in the Kalakkadu and Mundanthurai wildlife sanctuaries in Tamil Nadu, on the east side of the distribution. Groups there included individuals (more than one year old) with pale chocolate-brown coats and golden or silvery-golden hairs on their head. They were in groups that otherwise contained Nilgiri Langurs with typical black coats. They were seen in an area where langur groups were either completely isolated or abutted the home range of just one other group, indicating it may be a founder effect (if they were colonizing) or caused by inbreeding (if they had been isolated by deforestation).

Habitat. Evergreen, semi-evergreen, montane, and riparian forests; “sholas” (narrow tracts of evergreen forest, surrounded by grassland, usually with a stream running through them); and moist deciduous forests of the Western Ghats at elevations of 300-2400 m. Nilgiri Langurs are also seen in teak plantations close to natural forests.

Food and Feeding. Nilgiri Langurs feed on leaves (both young and mature), fruits, flowers, seeds, bark, insects, and termite soil. More than 100 plant species have been identified in their diet, but ¢.50% of their feeding time tends to be dedicated to a few species (three in one study, ten in another). In a study of two groups over 24 months in lowland riparian forest on the Mundanthurai Plateau, their feeding time was apportioned as follows: 44% young leaves, 19% seeds, 10% unripe fruits, 8% flowers, 5% ripe fruit, 4% mature leaves, and 10% other food items such as petioles, bark, pith, insects, gum, and wood. They fed on fresh ripe fruits during monsoon and post-monsoon seasons and gradually shifted to seeds with the onset of the dry season. Although they ate mature leaves, seasonally available young foliage, flowers, and fruits were preferred. In another study of a group of Nilgiri Langurs in tall, closed canopy, evergreen forest at Kakachi in the Agastya Malia range, the plant part of the diet included 25-5% young leaves, 25-1% fruits and seeds, 20-3% mature leaves (mostly from trees), 9-3% flowers and flower buds, 6-5% petioles of mature leaves, 5:7% leaf buds and initial flush of foliage, 4-2% leaves of unknown age, and 3.4% stems, bark, and undetermined items. In this study, young foliage was eaten from 56 species, and mature foliage was taken from only 39. Of 115 plant species in the diet, 58 were trees (including a tree fern), 32 were climbing plants, 13 were non-woody herbs,six were woody shrubs and bamboos, and six were parasites or epiphytes. Strong selectivity in their diet was demonstrated in that 45% of the diet came from only three tree species and the two most common trees in the forest contributed only 5%. Nilgiri Langurs also occasionally eat insects, including termites and stick insects. They raid potato, cauliflower, cabbage, and cardamom crops.

Breeding. Female Nilgiri Langurs do not show any known physical or behavioralsigns of sexual receptivity, although they have an everted pink clitoris that changes color, darkening at times and possibly associated with the periovulatory period of the menstrual cycle. A single young is born every 1-5-2 years, usually in May-November. Infants are born with pale skin and reddish-brown body hair, which gradually darkens and is close to adult coloration by 4-5 months of age. Mothers carry their young on their belly. Allomothering has been reported. Birth rates of groups in low-elevation riverine habitats are lower than those living at higher elevations (0-2 vs. 0-7 births per female/ year).

Activity patterns. Nilgiri Langurs are diurnal, arboreal, and infrequently terrestrial. They are known to move to moist deciduous forests in morning and return to evergreen forests at dusk. They move in single file, using the same route from branch to branch as their leader, usually in the middle forest canopy. Peak feeding time is in the morning and evening, and midday is rest time. They are generally found in the understory at heights of 5-9 m, but they sleep, feed, and sun themselves in the upper canopy at 12-24 m. They rarely go to the ground where they sometimes feed, fight, and play.

Movements, Home range and Social organization. The Nilgiri Langur typically lives in unimale-multifemale groups of ¢.7-9 individuals, but group sizes can vary from three to 27 individuals. Female emigration from the natal group is common and is a strategy to minimize competition and infanticide and increase access to resources. Dispersing males generally remain solitary until they can enter a group and take over as the dominant male. In one site where Nilgiri Langurs have been studied (Ootacamund), they also form small , ephemeral predominantly male, non-reproductive groups. Rarely, they form all-female groups. Sometimes new groups are formed by splitting—unusual among langurs. Home ranges vary in size (5-260 ha), evidently influenced by group size and dispersion, and the abundance and seasonality of foods in the different forest types. Home ranges of groups living in sholas tend to be larger. There is little overlap, and they are actively defended by adult males. When facing off with each other, males typically sit on high branches, open their mouths and emit continuous low buzzes that sound like creaking doors, and snap their heads upward with their mouths open, appearing to bite the air. Chases are accompanied by “whoops,” grunts, hiccups, and “hah-hah” calls. Group spacing is maintained by whooping sessions and vigilance by males. The adult male in a unimale-multifemale group rarely interacts with females. Females sometimes associate with Malabar Sacred Langurs (S. hypoleucos ) and Bonnet Macaques ( Macaca radiata ) until they form a heterosexual (one-male) group. When not hunted, Nilgiri Langurs reach high densities of 70 ind/km?.

Status and Conservation. CITES Appendix II. Classified as Vulnerable on The IUCN Red List (as Trachypithecus johnii ). The Nilgiri Langur is included in Schedule I, Part I of the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, amended up to 2002. Despite its full legal protection, it is still hunted because its flesh is considered highly flavorful. Its skin is used to make ornamental drums. It is also much sought after by poachers for its blood and internal organs, which are widely believed to cure variousliver and lung ailments and to act as an aphrodisiac (flesh and glands are used to “treat” asthma, and the blood is drunk fresh by locals as a “rejuvenator”). Body parts are used to make medicinal potions called “Karum Kurangu Rasayanam” (Tamil for “Langur tonic”). These direct pressures on Nilgiri Langurs are exacerbated by the steady loss, degradation, and fragmentation of their already limited habitat, as a result of mining, dam construction, and encroachment of plantations. As of 2003, the total wild population was estimated at less than 10,000 mature individuals. Nilgiri Langurs occupy a mere 16% of the total area of the Western Ghats. Areas surrounding sanctuaries and national parks suffer from anthropogenic pressures (extraction of timber and non-timber resources), and most tree species that are valued for their timber are also part ofthe preferred diet of Nilgiri Langurs. Domestic dogs prey on Nilgiri Langurs when they move between forest patches. Nilgiri Langurs occur in Eravikulam, Mukurthi, Periyar, and Silent Valley national parks and Aaralam, Brahmagiri, Chimmony, Chinnar, Grizzled Giant Squirrel, Idukki, Indira Gandhi, Kakkal, Kalakkad, Mudumalai, Mundanthurai, Neyyar, Parambikulam, Peechi, Peppara, Shendurney, Thattekadu, and Wyanad wildlife sanctuaries.

Bibliography. Ali et al. (1985), Bennett & Davies (1994), Groves (2001), Hohmann (1989a, 1990), Hohmann & Sunderraj (1990), Horwich (1972), Joseph & Ramachandran (2003), Karanth (2010), Molur et al. (2003), Oates (1979, 1982a), Oates et al. (1980), Poirier (1970), Ram & Srinivas (2000/2001), Roonwal & Monhot (1977), Sunderraj (2001), Tanaka (1965).

No known copyright restrictions apply. See Agosti, D., Egloff, W., 2009. Taxonomic information exchange and copyright: the Plazi approach. BMC Research Notes 2009, 2:53 for further explanation.

|

Kingdom |

|

|

Phylum |

|

|

Class |

|

|

Order |

|

|

Family |

|

|

SubFamily |

Cercopithecinae |

|

Genus |

Semnopithecus johnii

| Russell A. Mittermeier, Anthony B. Rylands & Don E. Wilson 2013 |

Cercopithecus johnii

| Fischer 1829 |